A note from the Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative project (artsprosjekt) “Sea Slugs of Southern Norway” (project home page), which ran from 2018 to the end of April 2020.

Dear all,

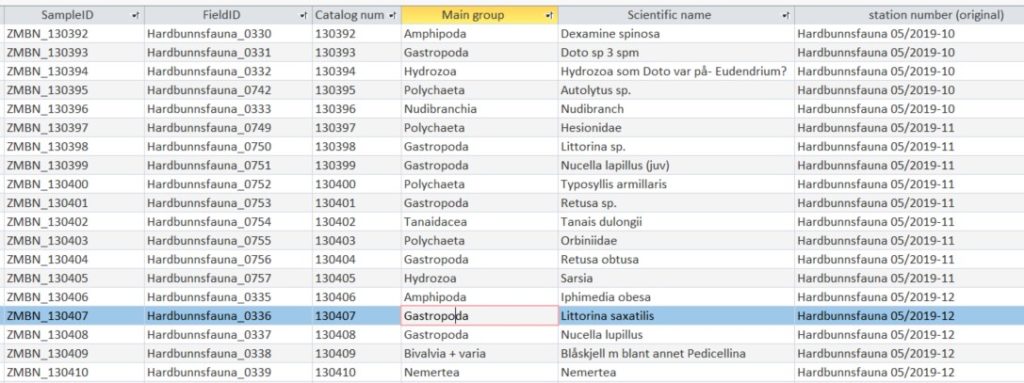

The Sea slugs of Southern Norway project reached its terminus at the end of April, with sending the last reports of our collection and research efforts to Artsdatabanken (the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre).

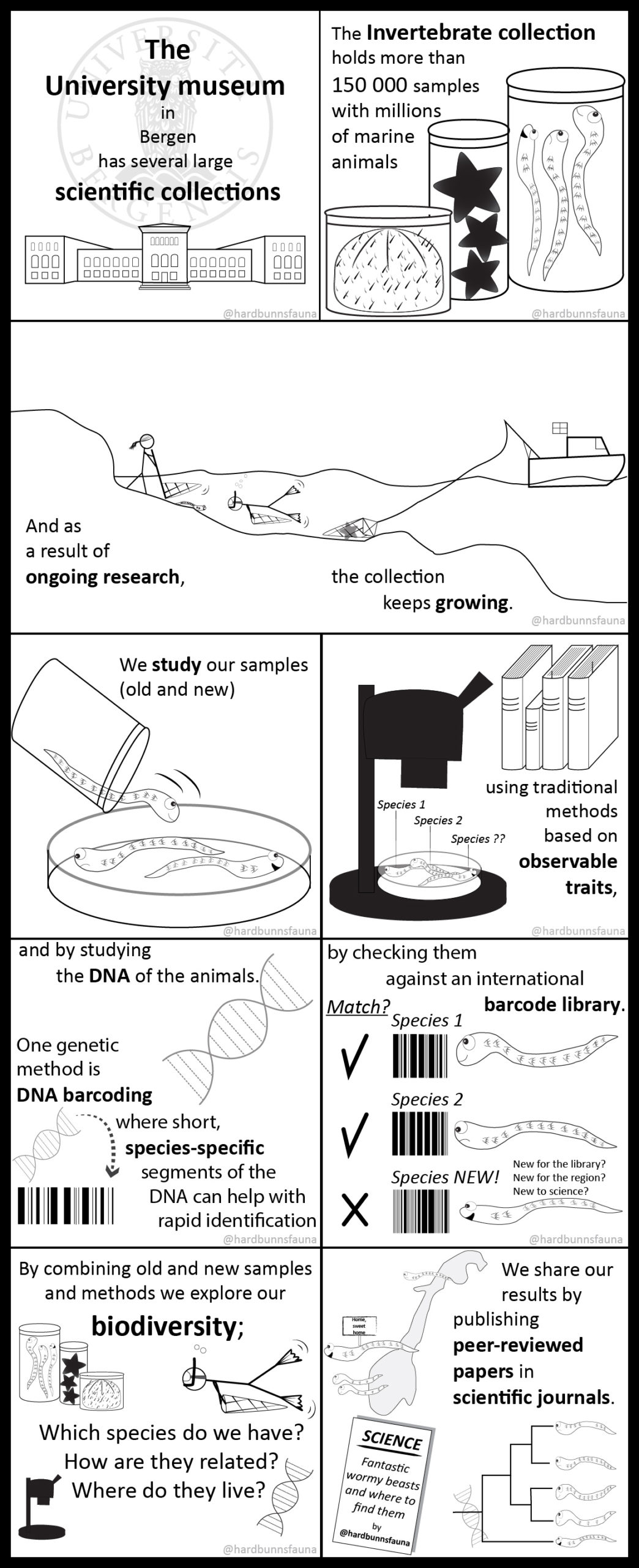

What we have been able to build up these last two years is of immense importance for the scientific collections of the Natural History Museum of Bergen (University of Bergen) and for (Norwegian) biodiversity research.

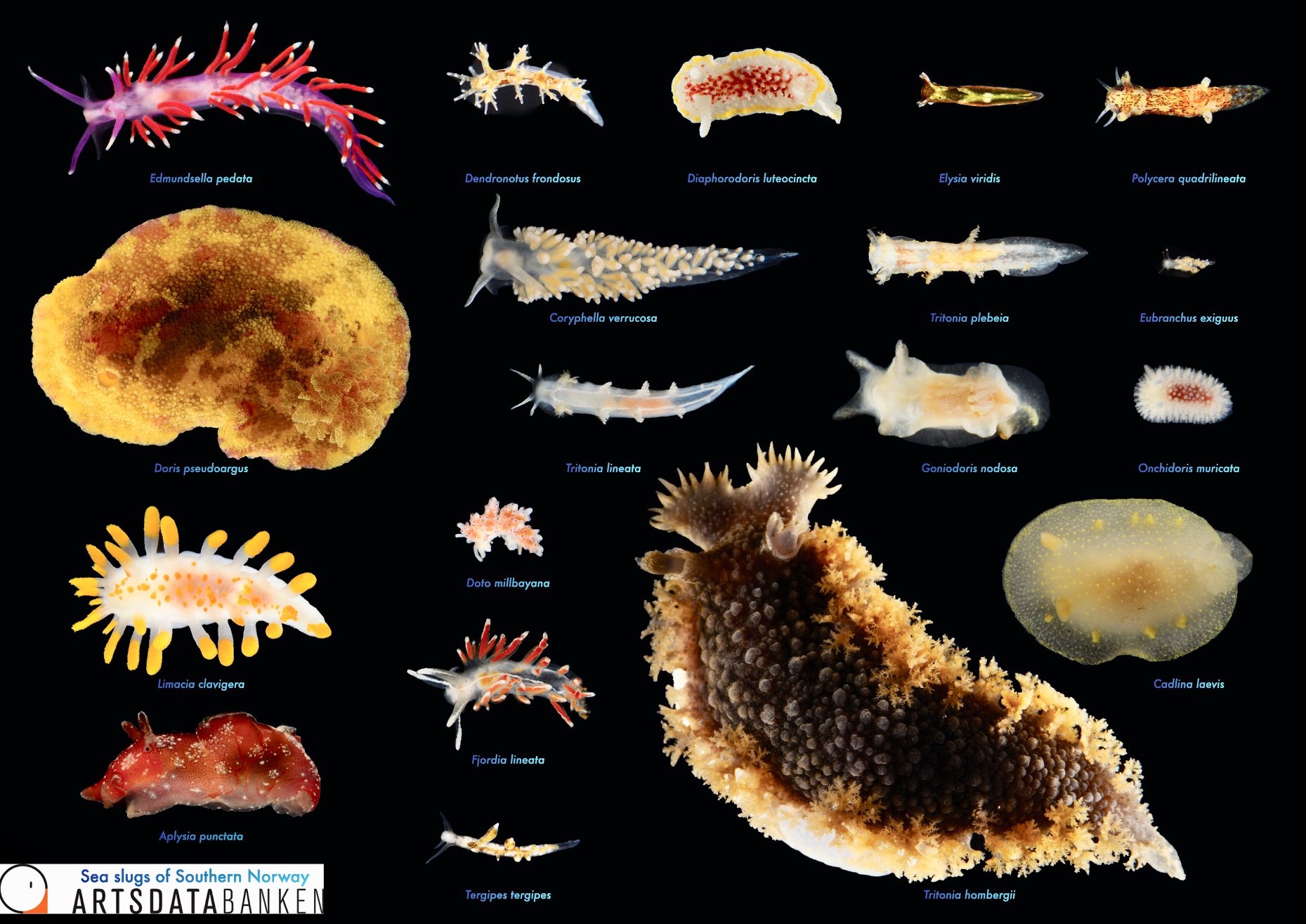

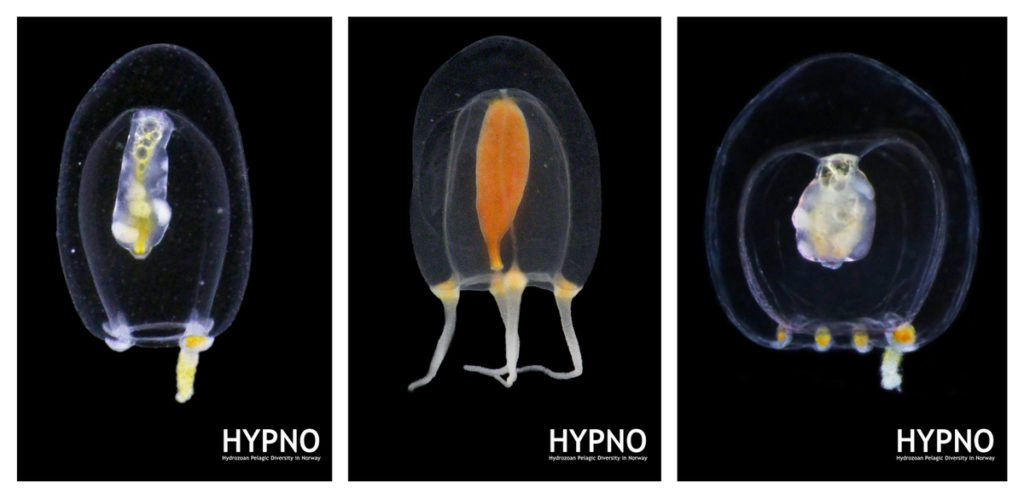

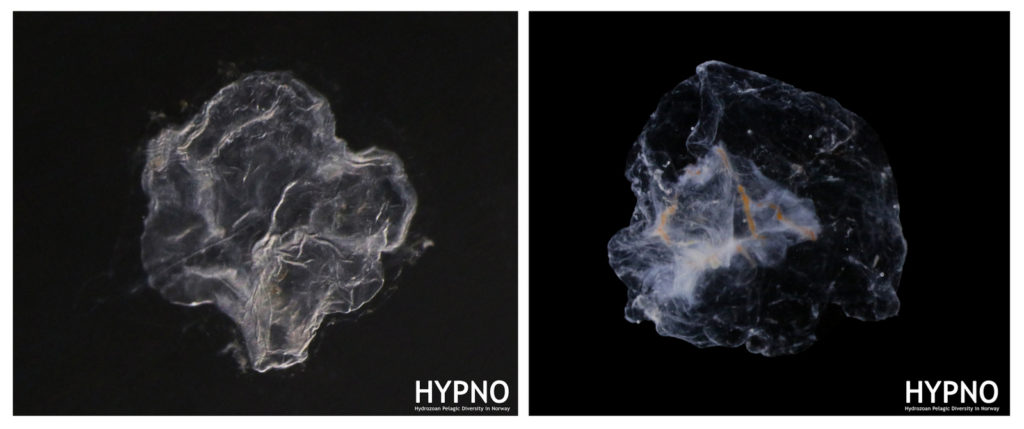

Sea slugs of Southern Norway managed to collect over 1000 lots covering 93 different sea slug species, of which 19 are new for Norway and a few new to science (we are working on it!).

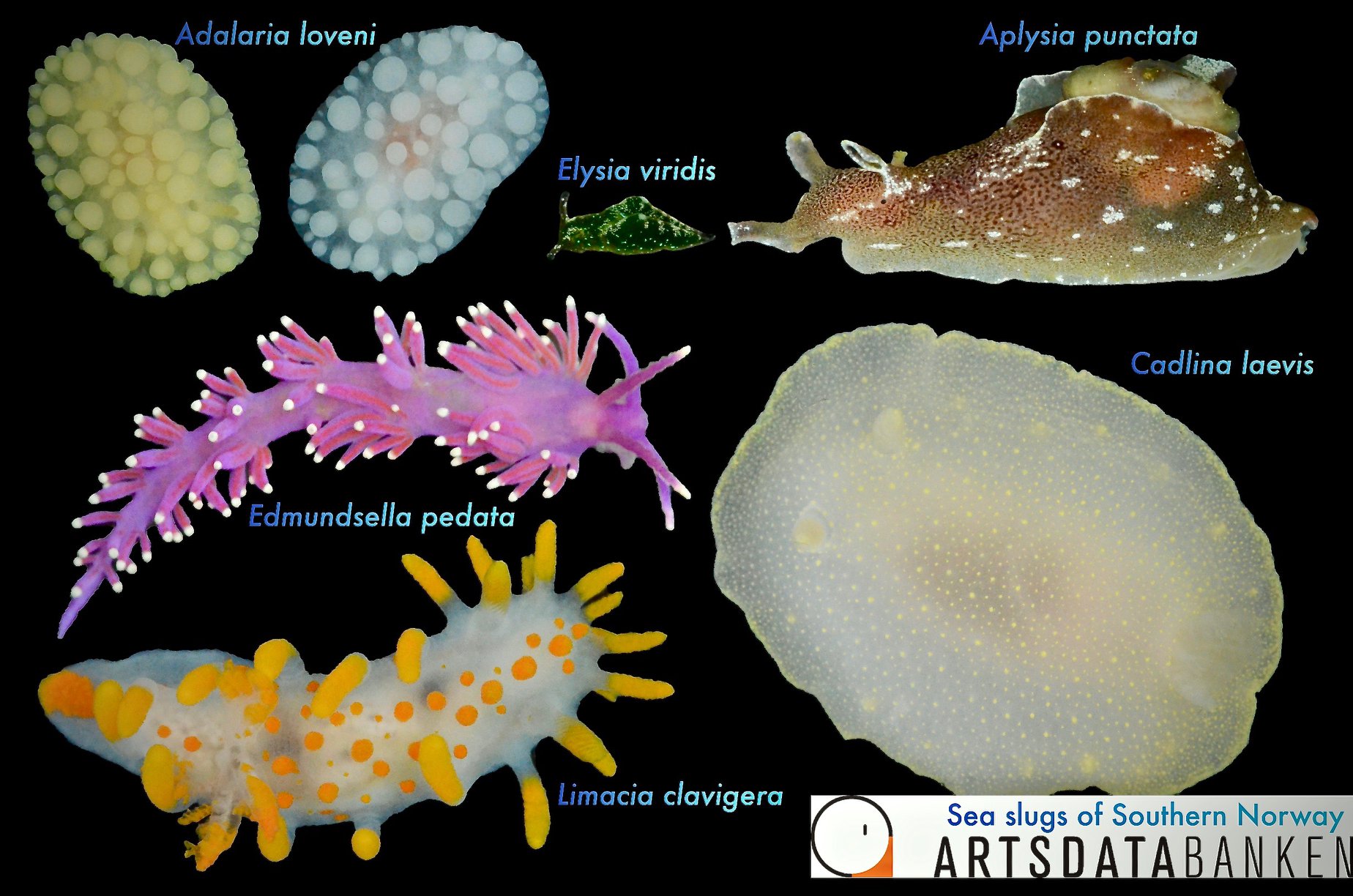

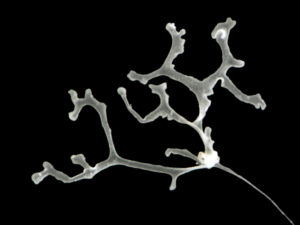

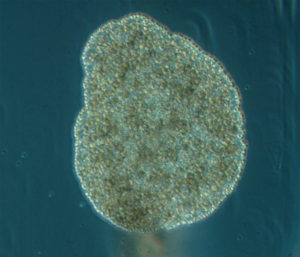

Below are photos of the species that were collected at different sampling events. The photos are made either by the researchers associated with the project, or by the amazing team of citizen scientists.

Look at these beauties!

- Mandal

- Askøy

- Bergen (Photos by Bjørnar Nygård)

- Drøbak

- Haugesund

- Larvik and Sandefjord

- Egersund

This would absolutely not have been possible without the special effort of our knowledgeable citizen scientists, and we would like to use this opportunity to name a few that were extraordinarily productive during the last years and provided the project and the Museum with valuable samples; Nils Aukan, Roy Dahl, Viktor Grøtan, Heine Jensen, Tine Kinn Kvamme, Runa Lutnæs, Ole Christian Meldahl, Jenny Neuhaus, Bjørnar Nygård, Anders Schouw, Erling Svensen, Cecilie Sørensen, Mona Susanne Tetlie, Anne Mari with Ottesen, Mandal Dykkerklub, Hemne Dykkerklubb, Slettaa Dykkerklubb, SUB-Studentes Undervannsklubb Bergen, Larvik Dykkerklubb, Sandefjord Dykkerklubb, and all the others that made big and small contributions.

A big thank-you to all contributors!

Would you like to know more about the citizen scientists part of the project? Check out this paper (starts on page 23) by Cessa and Manuel: Sea Slugs of Southern Norway: an example of citizens contributing to science.

- Drøbak Gulen with Tine Kinn Kvamme and Anders Schouw

- Haugesund with Anders Schouw and Anne Mari With Ottesen

- Larvik presentation for the dive club

- Drøbak fieldstation with Torkild Bakken

- Egersund team with Erling Svensen (Photo by Erling Svensen)

- Participants at Espegrend field station, where three Artsprosjekt (HYPNO, HArdbunnsfauna and SSoSN) organized a week long workshop

One of the core components of the projects success was our outreach effort on all kind of social media platforms. During these two years these platforms got much more traffic than we initially thought; apparently we have many Norwegian sea slug fans, within and outside of Norway!

Therefore we decided to continue with our outreach efforts to keep everyone engaged and up to date about these wonderful animals in our ocean backyard, but with some minor adjustments. Some of you might have already noticed a few changes during the last days on the Facebook page and our Instagram account. From today onward, the social media pages will cover sea slugs of all of Norway, and is now named accordingly. We also welcome a new admin to the facebook group: Torkild Bakken of NTNU University Museum. Welcome Torkild, the more expertise the better, so we are very happy to have you onboard!

We encourage everyone in this community to continue to be active and share your findings and knowledge with other.

Let’s carry on enjoying the wonderful world of sea slugs of Norway!

-Cessa & Manuel