Haugesund 3rd till 10th of July 2018.

by Cessa Rauch

The Sea slugs of Southern Norway project is going strong with already the second fieldwork trip checked off from our to-do list. Sea slugs of Southern Norway is a two-year project funded by Artsdatabanken aiming to map the diversity of sea slugs along the Southern part of the Norwegian coast. From around Bergen, Hordaland to the Swedish border, as this particular area of Norway has a huge gap of about 80 years without any dedicated work on sea slugs diversity being carried out. In May the project had its official kick off with a successful expedition to Drøbak, a little village near Oslo in the Oslofjord, where we were able to collect around 43 species, and met up with our dedicated collaborators from that area.

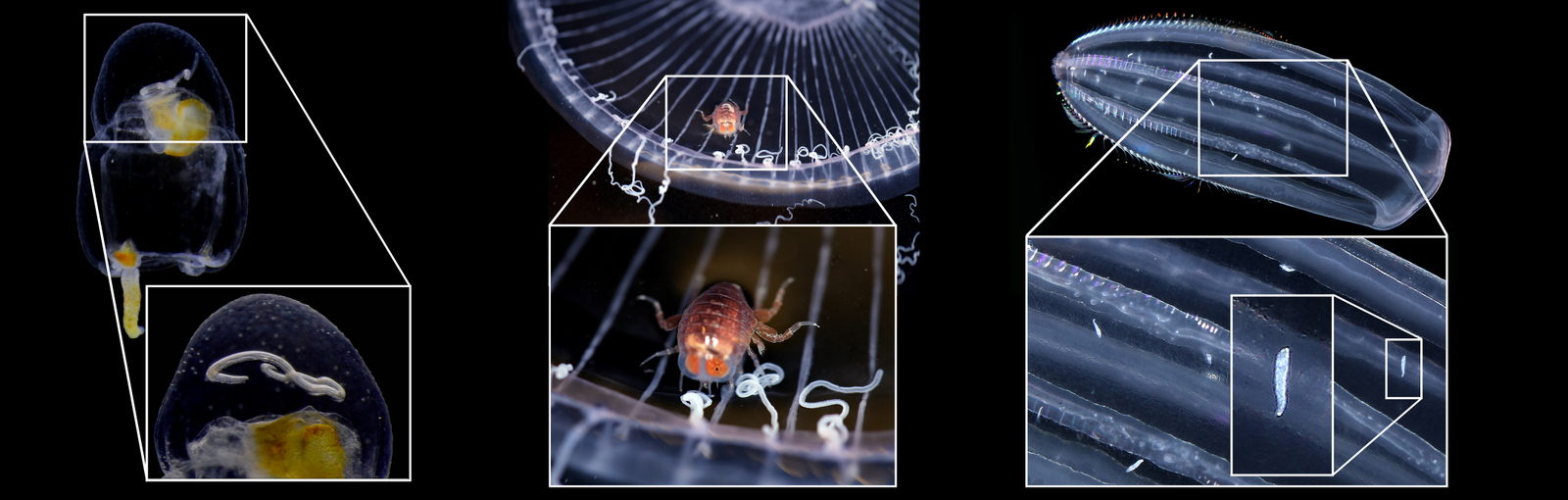

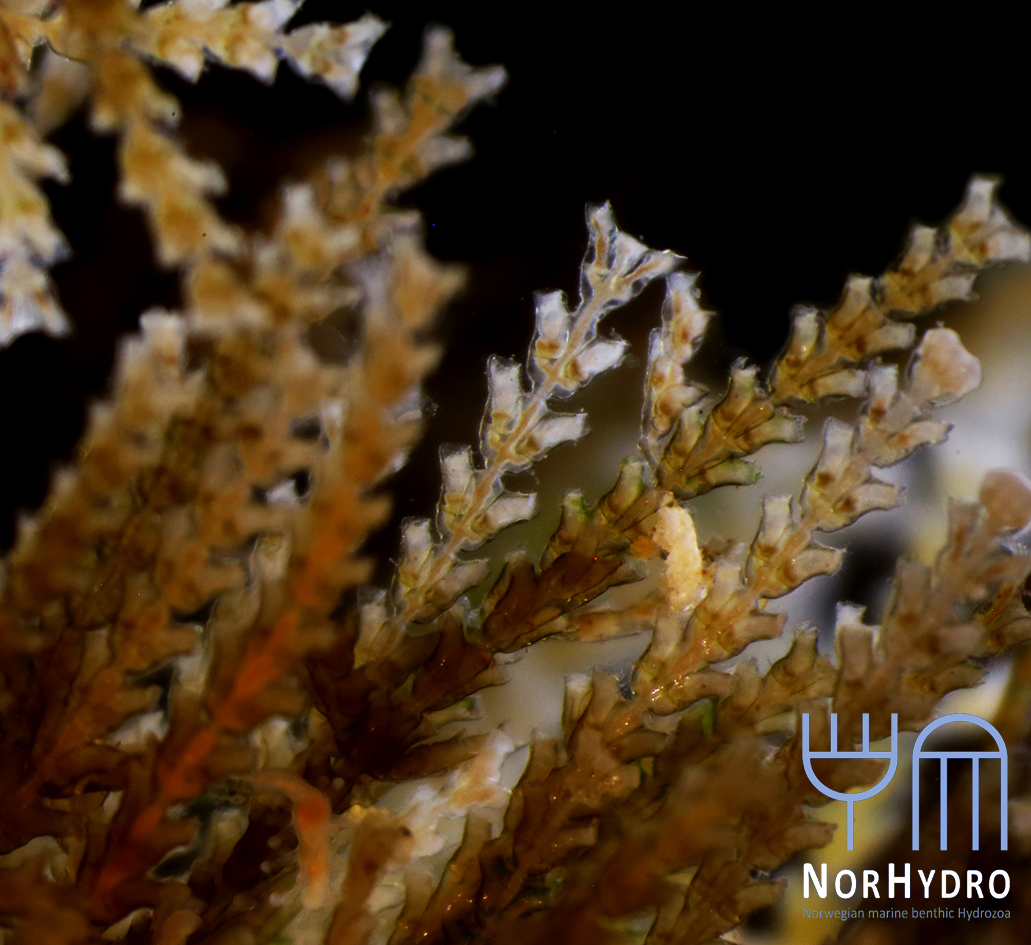

A selection of the species collected during the Drøbak expedition in May 2018. From left to right; top: Jorunna tomentosa, Doto dunnei, Facelina bostoniensis, middle: Doto coronata, Fjordia lineata, Limacia clavigera, bottom: Caronella pellucida, Microchlamylla gracilis, Rostanga rubra, photo credits: Anders Schouw

From the beginning we have made an effort to engage divers and underwater photographers passionate about sea slugs and establish a network of Citizen Scientists, and the response was extremely positive. Citizen scientists are volunteers that help out scientists by providing them with data as a hobby in their spare time. Their many years of experience result often in the accumulation of an immensely valuable knowledge about the taxonomy and ecology of these animals, which they eagerly share with us. We shall say, that the success of our project heavily rely on their input and willingness to help collecting samples, particularly because of the restrictions with scientific diving in Norway that we researchers face, that basically hamper any possibility to use this method for collecting slugs during our working time.

Dive camp Haugesund 2018

So far, we have citizen scientists helping us collecting sea slugs in the Oslofjord area, Egersund, Bergen, and Kristiansund. As you can see we miss a lot of coastline here still. Therefore, we decided to participate in the dive camp in Haugesund this year to see if we could get in touch with more enthusiastic hobby divers.

The dive camp was organized by the Slettaa Dykkerklubb Haugaland. Started in 2015, they are a relatively young club, but they grew very fast and have currently around 200 members. They are well known for the many activities they organize throughout the year that are often open to anyone who likes to participate.

Dive camp Haugesund pamphlet and picture

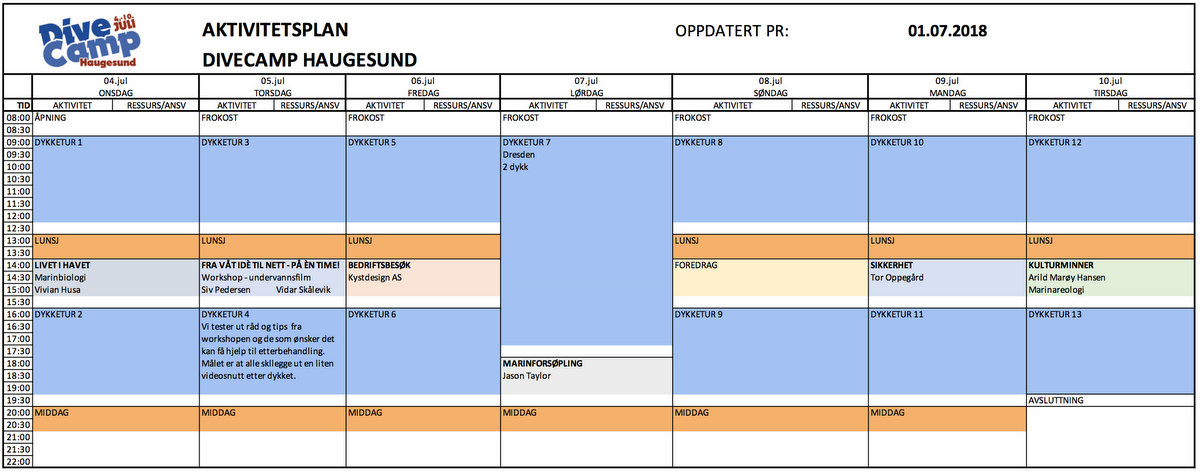

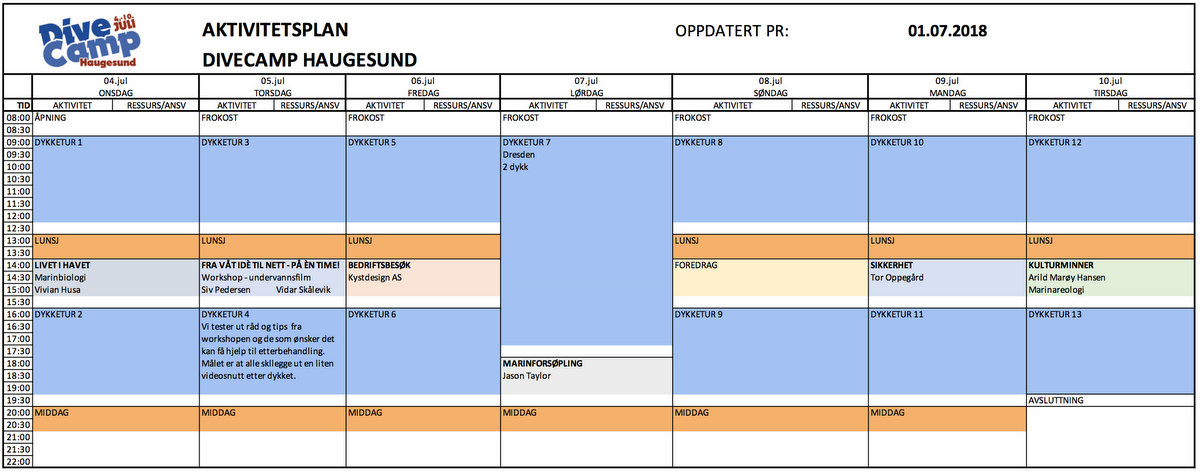

The timetable for the week (click to enlarge)

This year they decided to organize an actual dive camp that took a week and offered two dives a day, camping spot, breakfast, lunch, dinner, and every day an interesting talk or tour related to diving. It was from 4th of July until the 10th and every day between the dives the participants had interesting meet-ups with marine biologists (like Vivian Husa), underwater photographers (Siv Pedersen and Vidar Skålevik from WEDIVE.no), and underwater artist Jason deCaires Taylor. We also visited the company Kystdesign, and we got a safety lecture form Tor Oppegård.

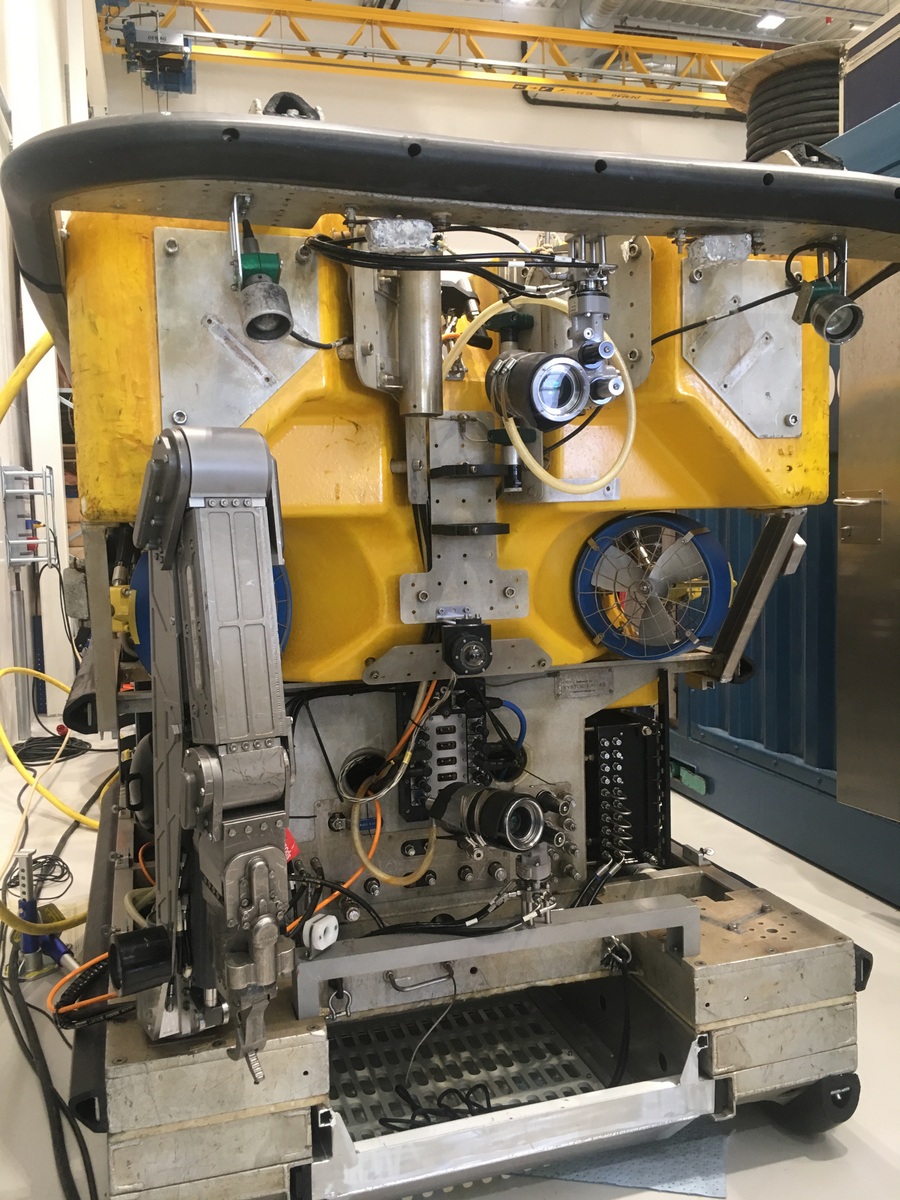

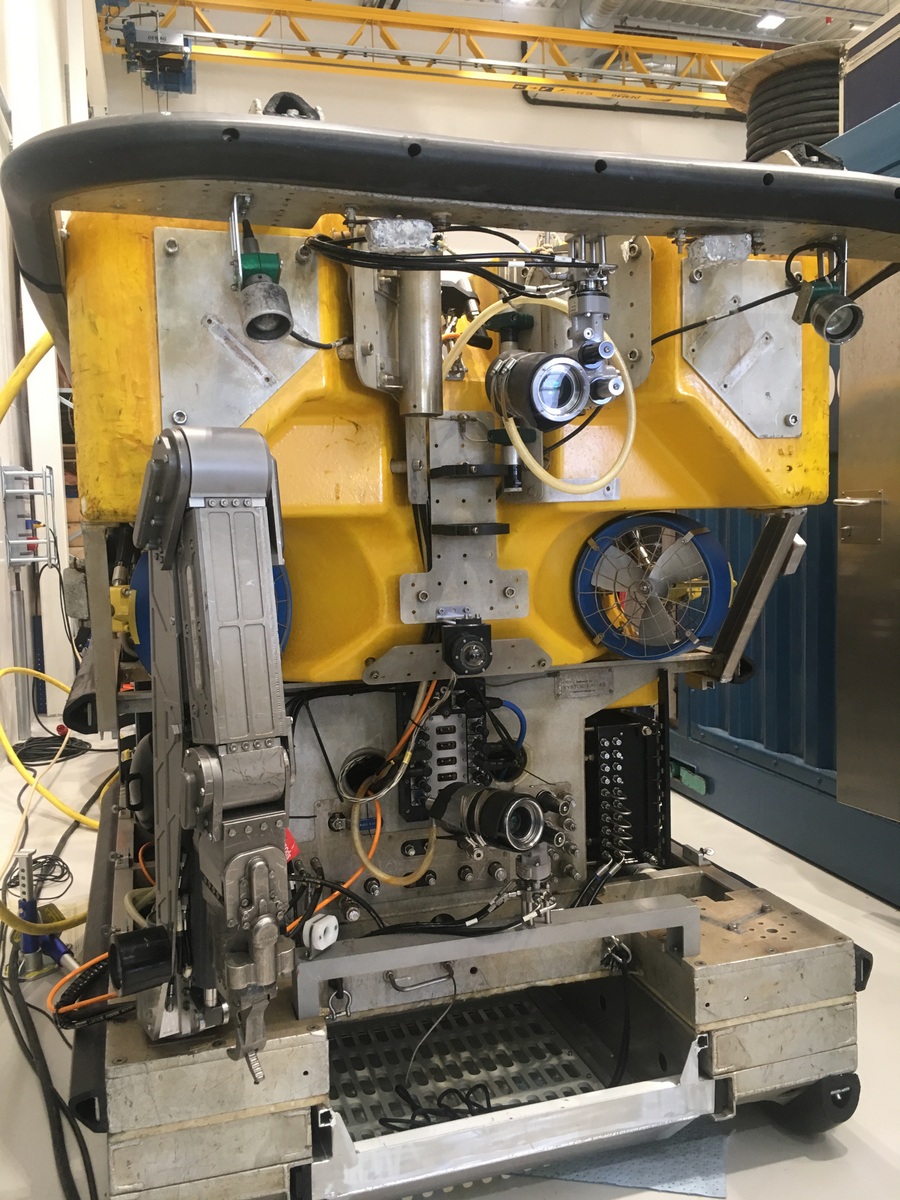

One of the remote-controlled submarines that were presented during the tour

A very busy and informative week! It was a great success for the participants and organizers and there will be a similar event again next year.

There and back again

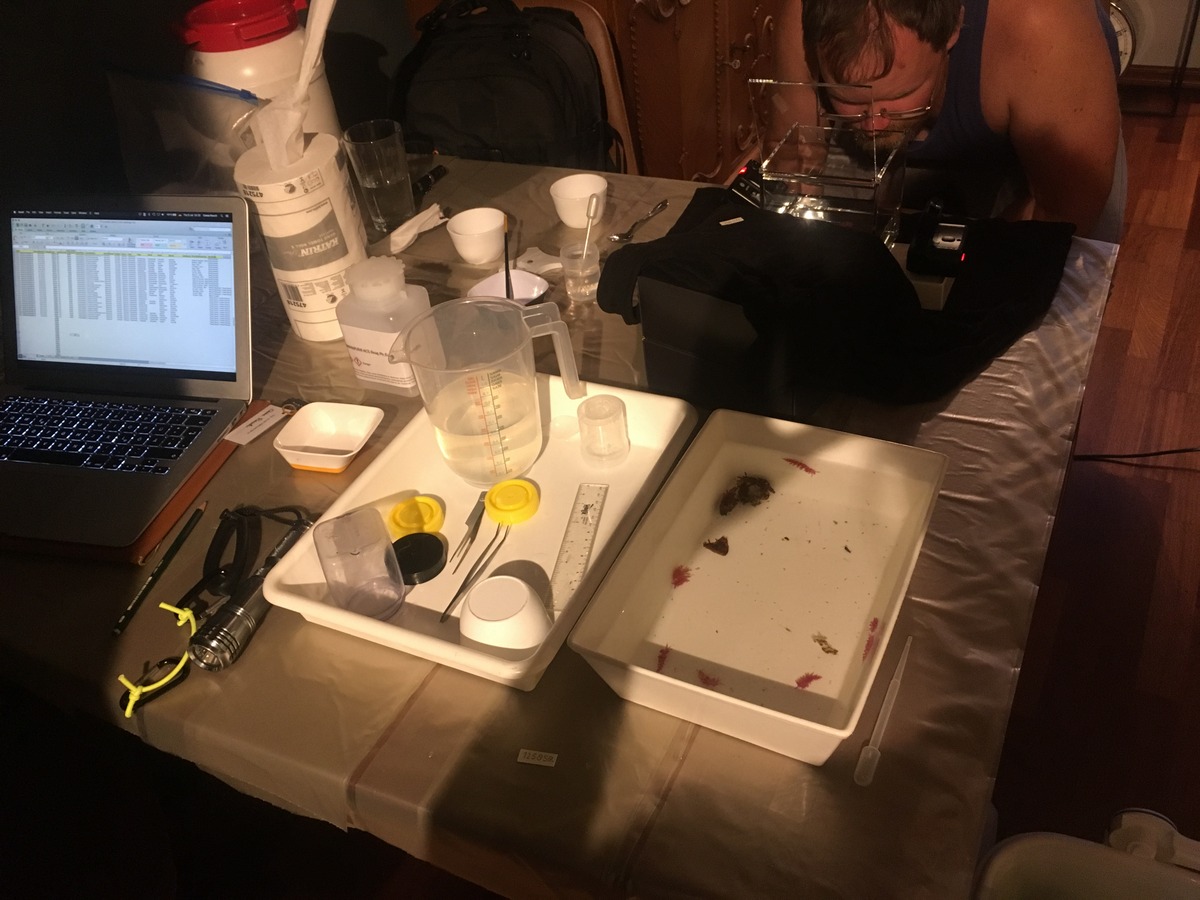

Microscope in the living room

The day before the camp started, I met with citizen scientist Anders Schouw, and we drove that evening from Bergen to Haugesund to check into our rented Airbnb flat.

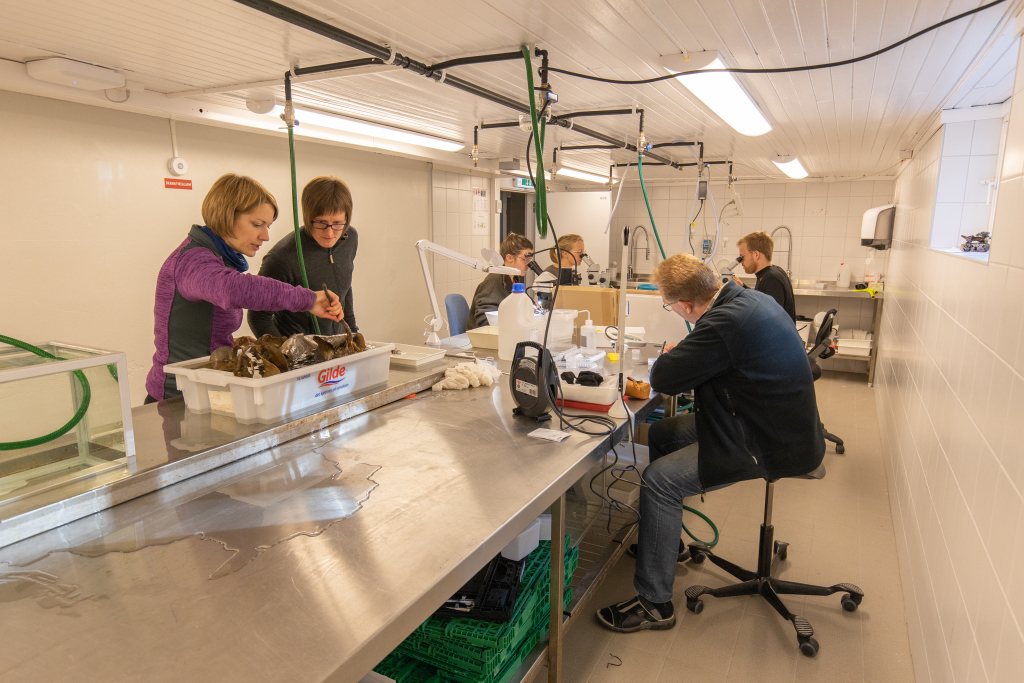

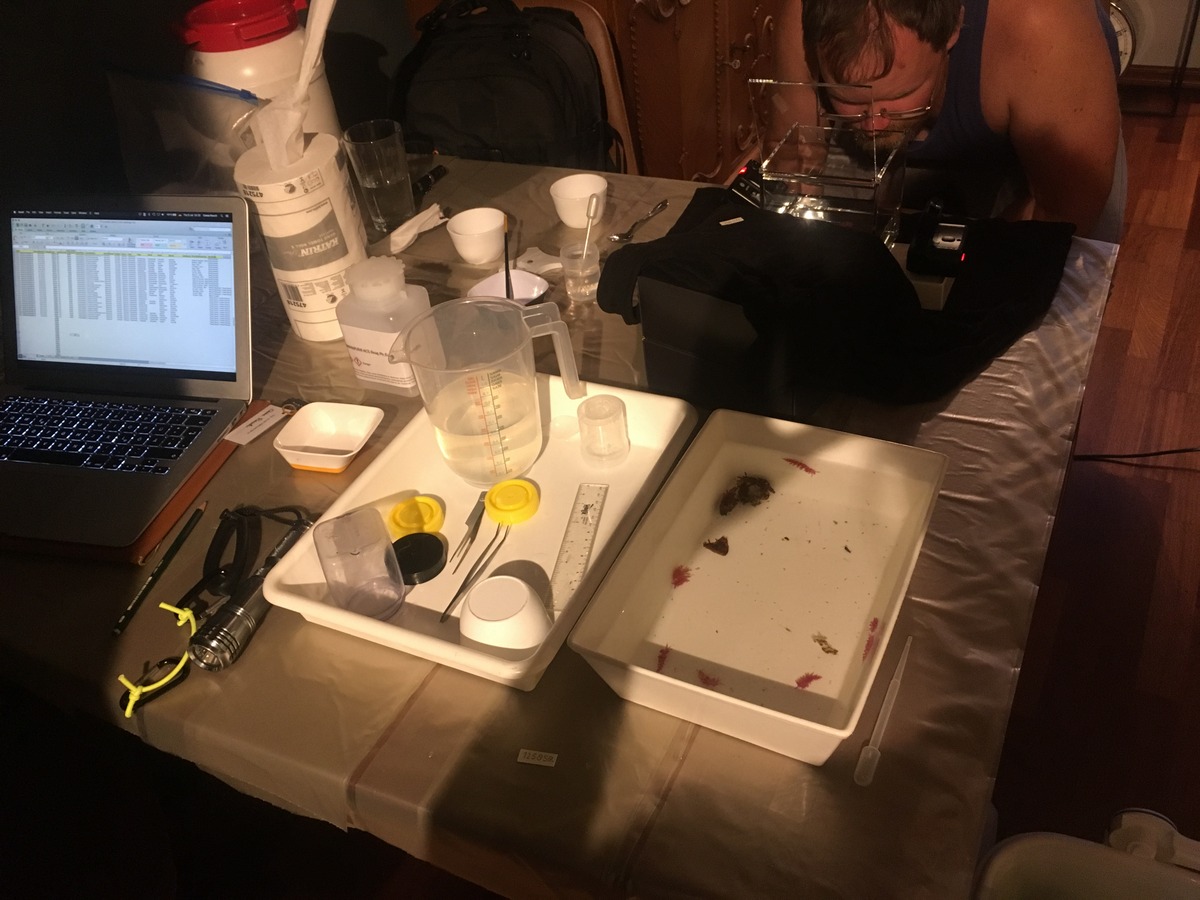

Although the Dive Camp had arranged a camping ground for visitors, we decided to stick with renting a flat, in order to have our equipment properly installed. Once arrived, we had to add some adjustments to the apartment. The dining area was converted to a sea slug studio with trays and camera equipment installed. The living room was now our little laboratory with a microscope and laptops.

The dining area converted into our mobile sea slug studio and picture

I can reassure you that we left everything clean and tidy!

The review of the owner, after I left our converted laboratory for an actual apartment

The next day we met very early in the morning at the seashore to be picked up by one of the organizers of the dive camp.

Pick up by speedboat in order to cross the water

The actual event took place on a tiny island just a short boat ride away from the city center of Haugesund. From there we took the boat Risøygutt from Thomas Bergh that we used in order to commute from the island to all the beautiful diving spots surrounding Haugesund. The first day we met up with Klaus and Are Risnes (father and son) as one of the participants of the camp that day.

During the week, and especially during the weekend, the number of participants increased and at a given time we had to go out with two boats in order to bring the more than 20 divers to the dive spots. Anders would be diving with Thomas while Karl Oddvar Floen and Torbjørn Brekke were leading the dive.

Originally built as a shrimp boat, Risøygutt has converted to a diving boat years ago, and the current owner Thomas Bergh, continued to use it for diving activities

My main purpose during the dive camp was providing everyone with collecting jars, that they took with them every dive, in search of sea slugs.

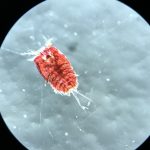

Klaus Risnes after a dive within his collecting jar with the sea hare Aplysia punctata, notice the purple colored water, ink from the sea hare they produce when they are disturbed

The cool box with sea slug samples on Risøygutt, accompanied with Anders’ photography gear

Because we needed the species alive for photography and species identification, I brought a cool-box with ice with me on the boat were the jars with sea slugs were kept, in order to keep them cool.

I was running around on the boat providing collecting jars to the divers during the whole week, but as the number of participants during the week increased, the collecting jars were running out.

Halfway, Anders and I decided to visit the local supply store and purchased a bunch of extra collecting jars for all the enthusiastic participants willing to catch some sea slugs for us

Collecting jars full with different species of sea slugs

Different sea slug species in a collecting jar (accompanied with three flatworms)

Every day after the two dives, Anders and I returned to our “Airbnb-lab” and started working on the sea slugs, that meant sometimes short nights, and as you guessed it, the more species, the less sleep

Working on collected specimen far past bedtime

The species collected were luckily all photogenic and we were very happy with the results!

Anne Mari With Ottesen helping out with sea slug sorting

Luckily we got many enthusiasts helping out and one evening Anne Mari With Ottesen joined us on the identification of the sea slugs.

Halfway in the dive camp week I gave a lecture about sea slugs in general and about the Sea slugs in Southern Norway project. It helped divers to spot sea slugs easier as they become better informed about what and where to look for.

This helped tremendously as we continued to get different species of sea slugs after every dive. At the end of the week, the count was on 22 species!

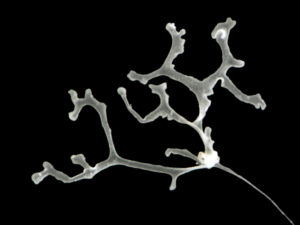

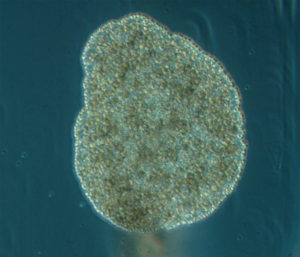

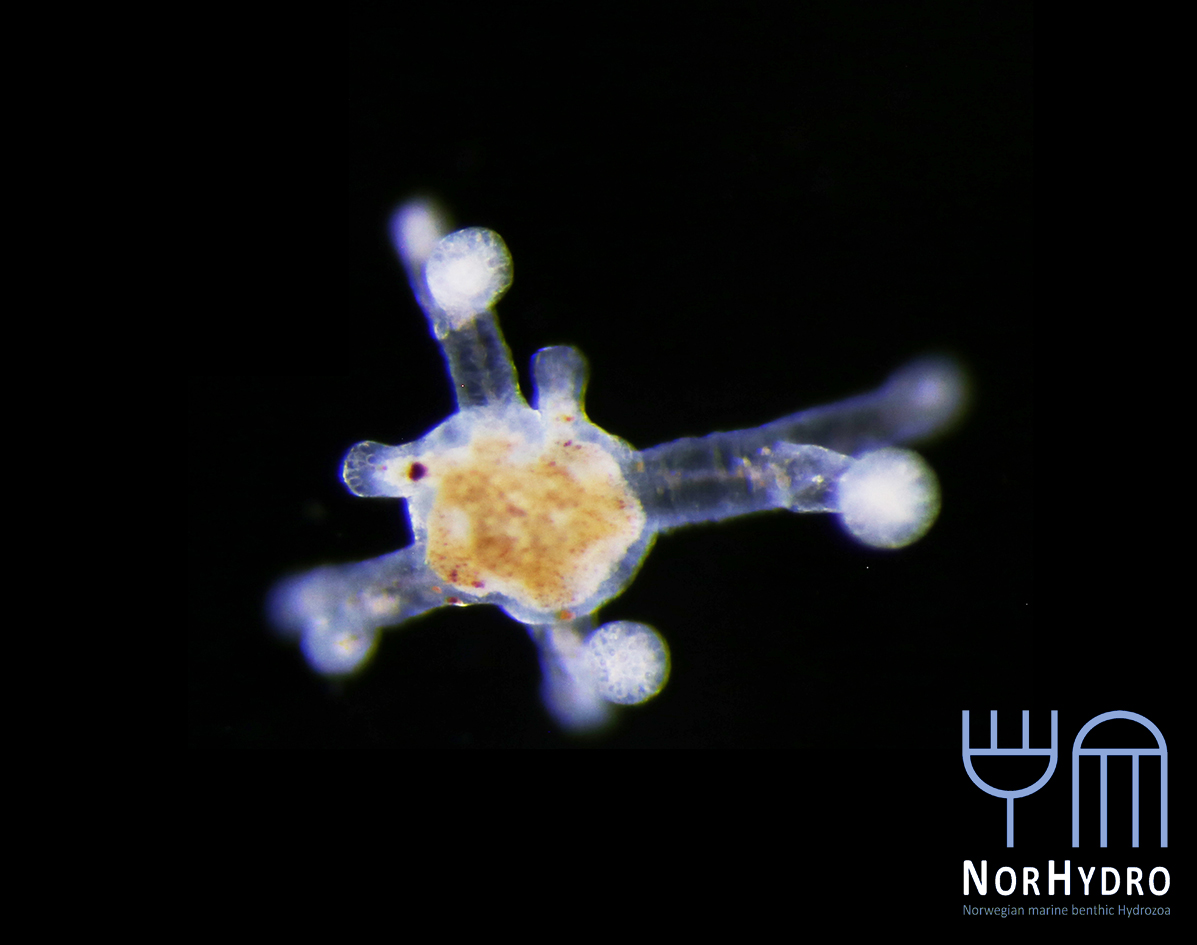

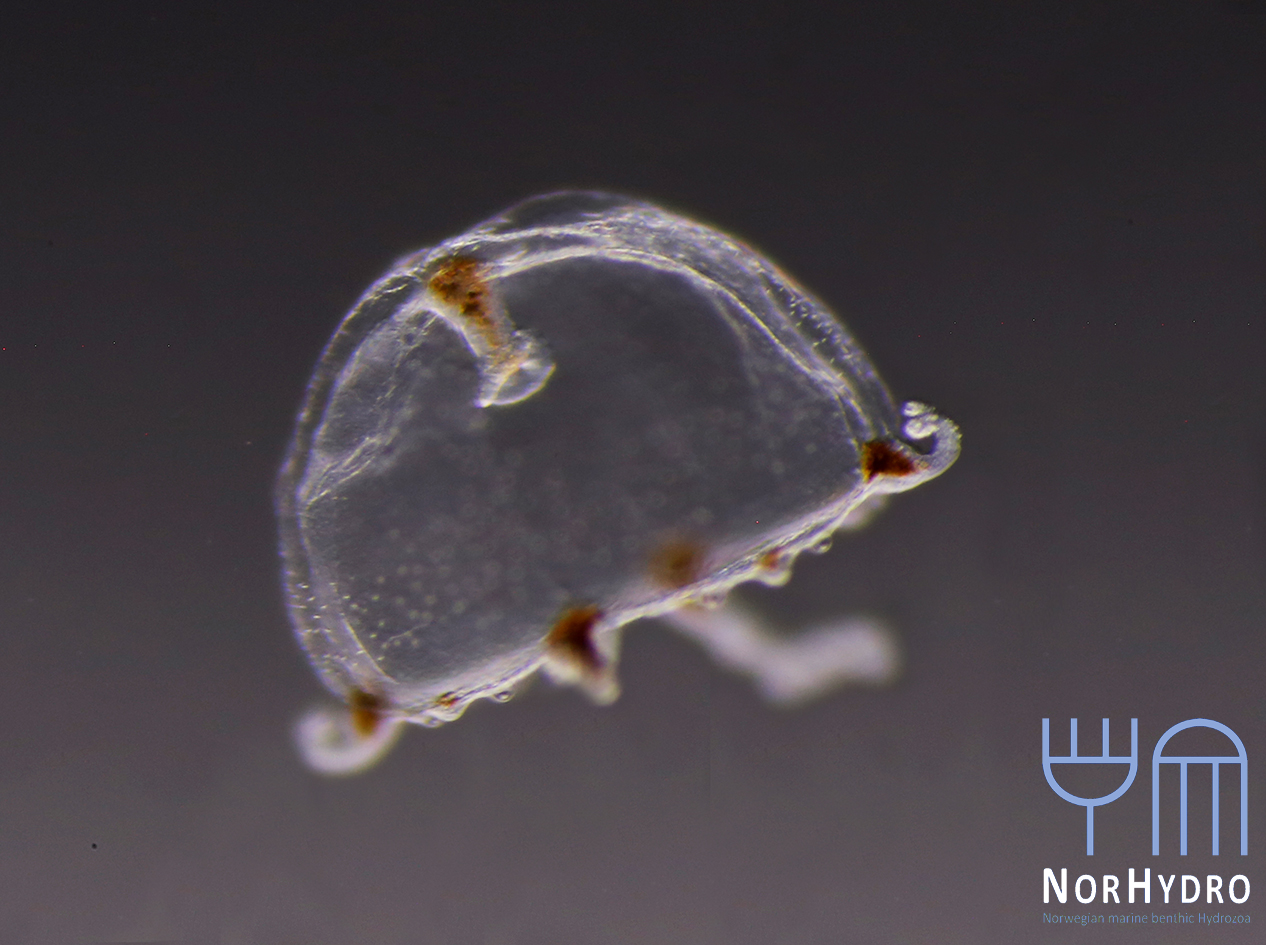

Catch of the week, as it is our most rare species so far in our Artsdatabanken database, Aegires punctilucens, photo credits Anders Schouw

Photogenic Edmundsella pedata, photo credits Anders Schouw

Besides the good weather, the delicious seafood and many new friendships made, with the number of new slug species added to our list and the many new citizen scientists volunteering for our project now, I could say that the dive camp was a success. We will continue to collaborate with Slettaa Dykkerklubb and hopefully in the future will host a sea slug course for its members and participate with the dive camp again next year, I can’t wait. Tusen takk!

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Anders Schouw for all his effort in helping out during this week and I especially would like to thank him for his stamina during long days and short nights sorting the sea slugs!

We also would like to thank the organizers of the dive camp and Slettaa Dykkerklubb members; Åge Wee, Lars Einar Hollund, Thomas Bergh, Elisabeth Bergh, Torbjørn Brekke, Karl Oddvar Floen, Anne Mari With Ottesen and the numerous other enthusiastic participants that helped us out during the week! And a warm welcome to our new clan of citizen scientists!

Interested in our Sea slugs of Southern Norway project? Become a member of our Facebook group and get regular updates.

Further reading

Are you interested in the Slettaa Dykkerklub Haugaland? Visit their Facebook group or their website for more information.

Want to know more about underwater photography? Check the personal underwater photography blog on Facebook or visit this website for tips and tricks.

Always wanted to know more about Jason deCaires Taylors’ underwater art? Visit his website. Did you know that Jason has also underwater art installed in Oslo? Check this out;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ksl5WgK7eHc

Explore the world, read the invertebrate blogs!