February 14th -18th 2022

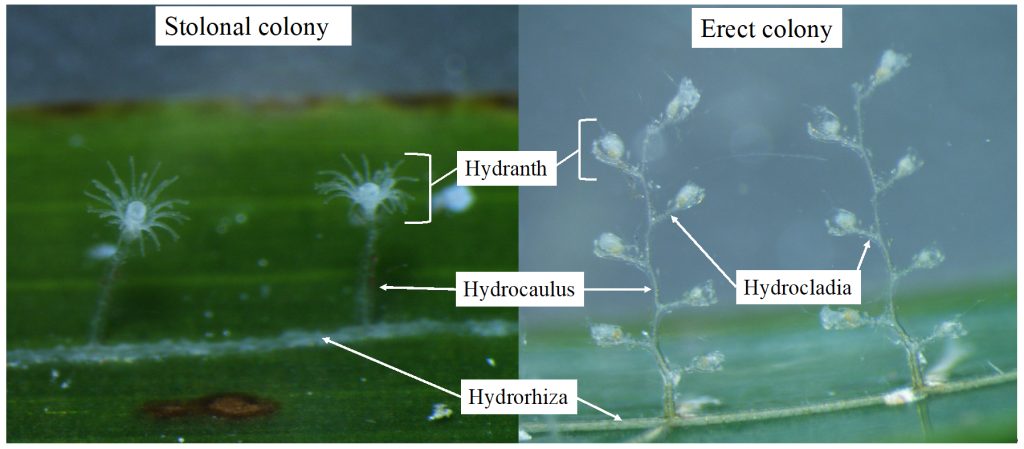

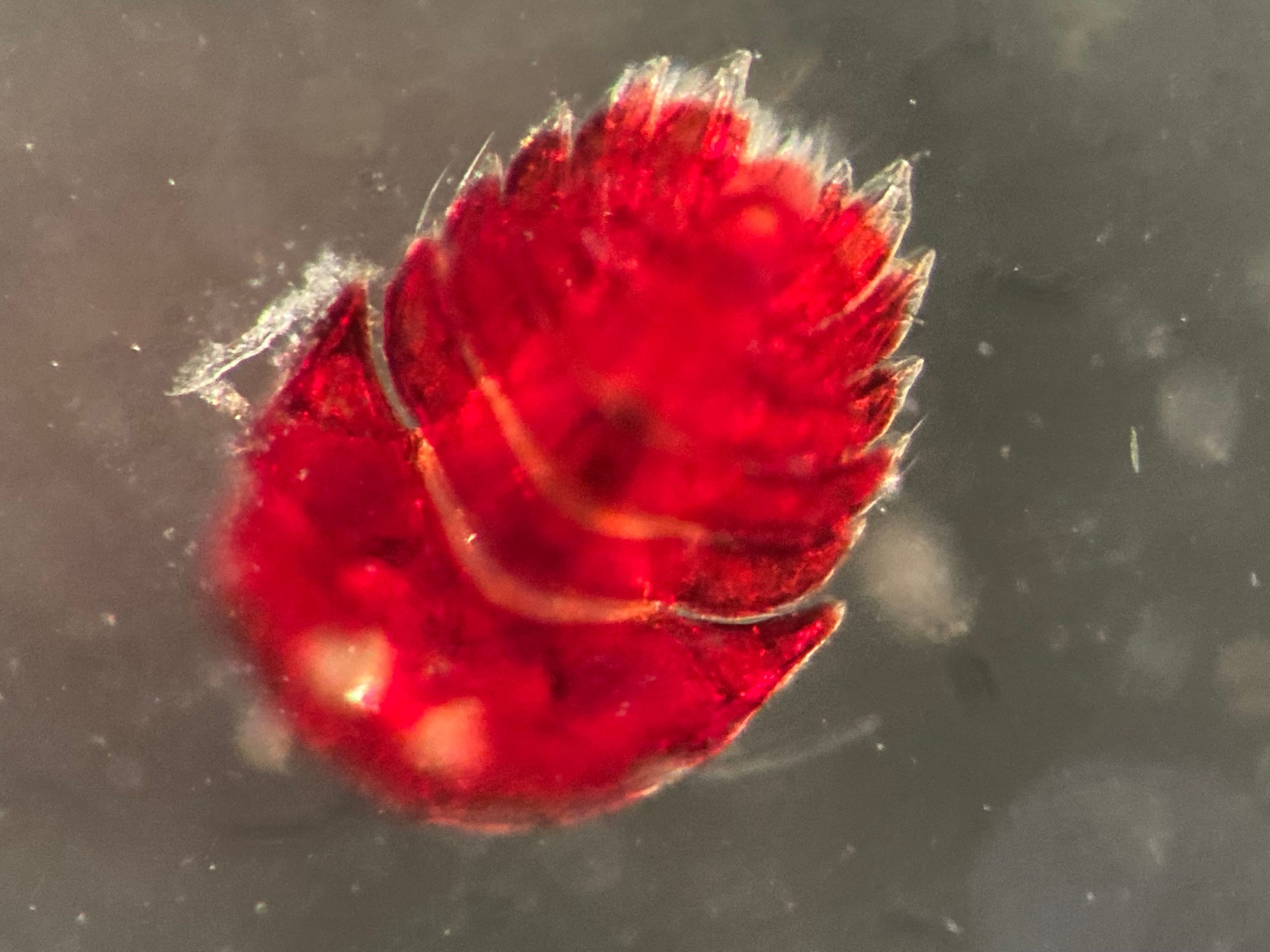

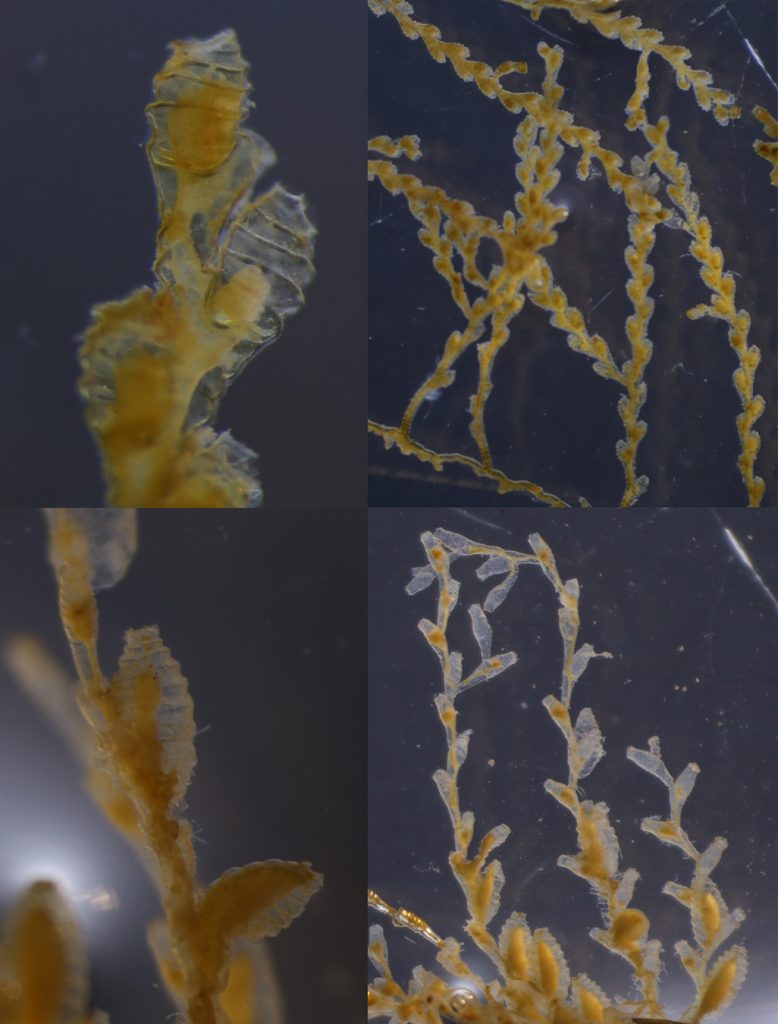

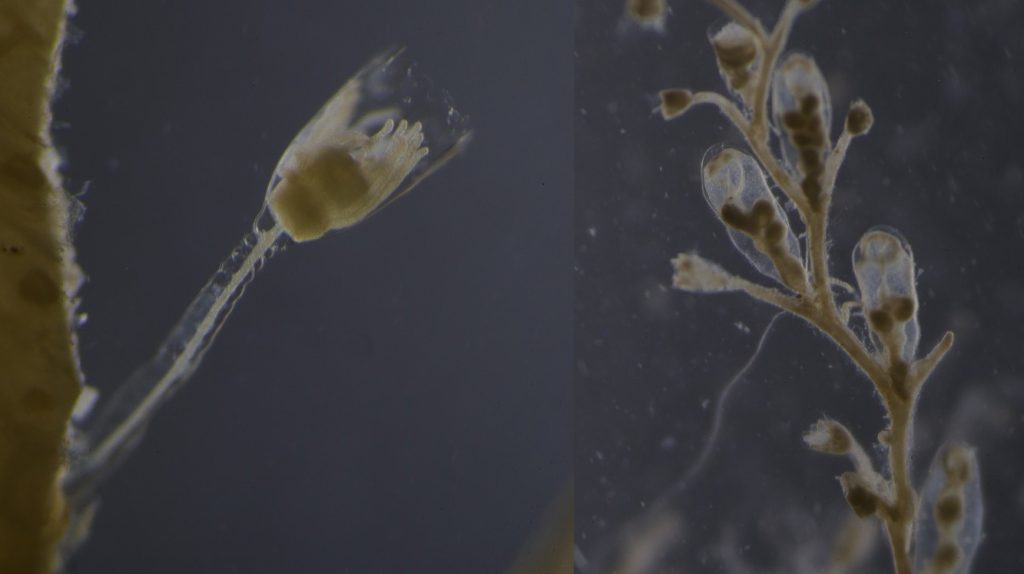

The Bryozoa are maybe not the most famous of animals, so let’s start with a quick rundown: Bryozoa, also known as Polyzoa, Ectoprocta, or moss animals (mosdyr, på norsk) are a phylum of aquatic invertebrates. Bryozoans, together with phoronids and brachiopods, have a special feeding structure called a lophophore, a “crown” of hollow tentacles used for filter feeding, which you can see in action in the video Tine captured:

In Norway we have 292 species registered, of which 281 are marine (Kunnskapsstatus for artsmangfoldet 2020, pdf here). It is estimated that the actual number of species present is higher. Further, several known species are considered “door knocker species” that may establish here within the next 50 years.

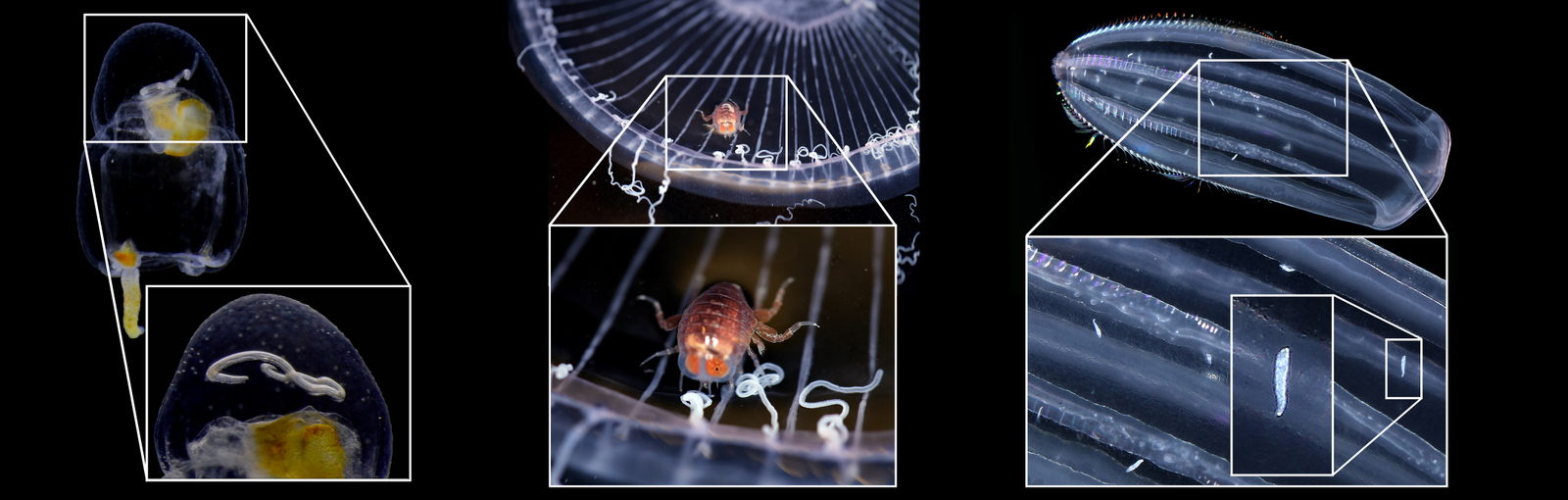

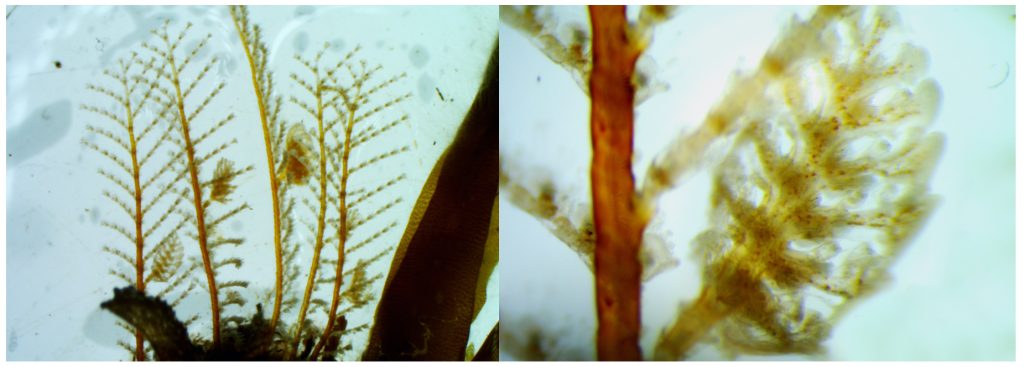

Bryozoa mostly live in colonies made up of tiny individual animals called zooids, which grow in a variety of shapes, and some of them provide structural habitats for other species. They are food for many other animals, namely nudibranchs, fish, sea urchins, pycnogonids, crustaceans, mites and starfish. Marine bryozoans are often responsible for biofouling on ships’ hulls, on docks and marinas, and on offshore structures. They are among the first colonizers of new or recently cleaned structures, and may hitchhike to new places with marine traffic. (Bonus: they have a super interesting fossil record, and this can be used to tell us more about the world in the way back!)

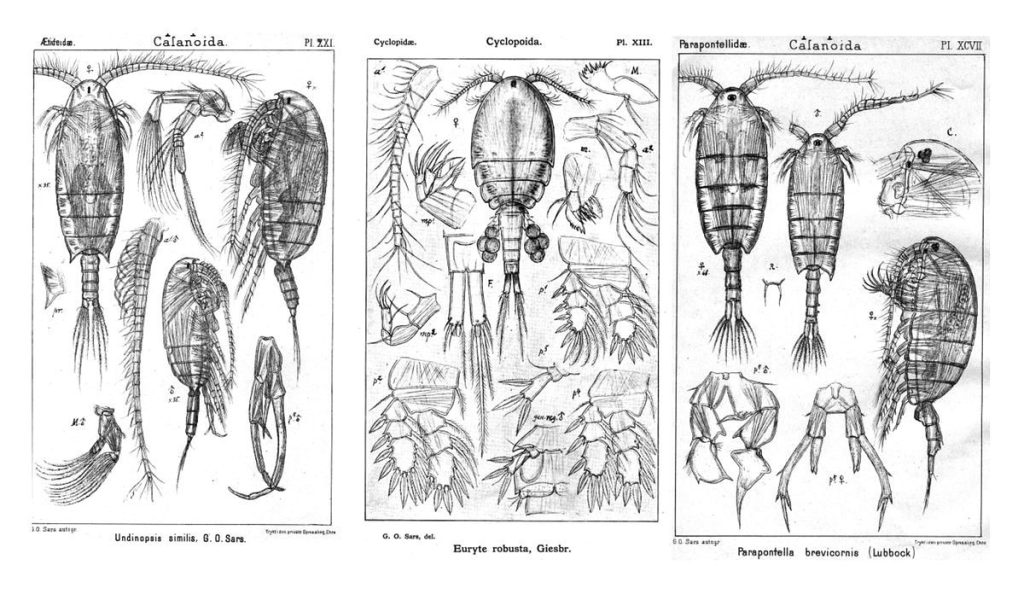

A few of the shapes the colonies can grow in. Pictured are 1: Membraniporella nitida 2: Bugula sp. 3: Flustrella hispida 4: Crisia eburnea

They are one of the focus groups of Hardbunnsfauna: there is still a lot we do not know about them!

Ernst Haeckel – Kunstformen der Natur (1904), plate 23: Bryozoa. Public domain, accessed through Wikipedia

Planning in a pandemic is not easy, and we have had to postpone our plans for this gathering several times. The second week of February we could finally gather our “Team Bryozoa” here in Bergen for a week of in-depth studies of these fascinating animals.

Team Bryozoa (centre), from left Piotr, Mali, Jo and Lee Hsiang, and some of the animals they studied. Group photo by Piotr Kuklinski

In total we were 11 participants;

University Museum of Bergen: Endre, Jon, Tom and Katrine,

Natural History Museum in Oslo: Lee Hsiang and Mali,

NTNU University Museum: Torkild, Tine (MSc. student) and Tiril (MSc. student),

and our two visitors from abroad:

from the Institute of Oceanology, Polish Academy of Sciences came Piotr,

and from the Heriot Watt University (Orkney Campus), Joanne.

The main focus of the workshop was to get as many samples and species as possible identified, work though the DNA barcode vouchers from samples submitted in advance and reach a consensus on which species the dubious ones were, to network with our colleagues, and to include the students in the work and the team. It all went swimmingly, and a we had a very productive and enjoyable week!

check out @hardbunnsfauna on Instagram for more!

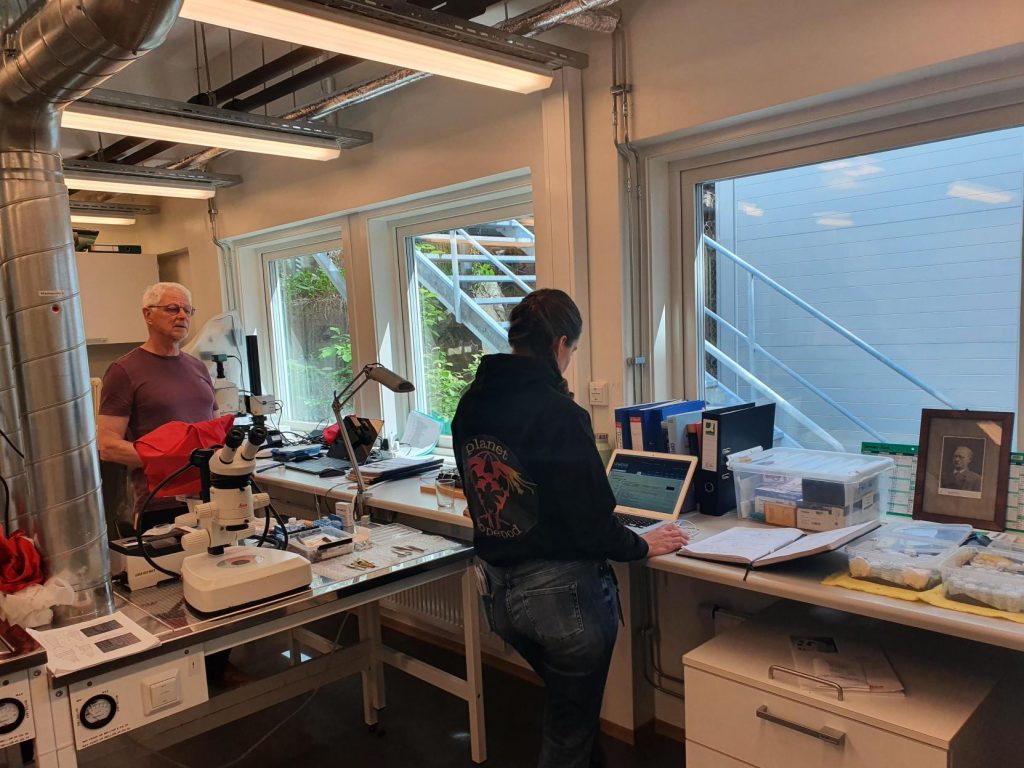

We set up camp on Espegrend Marine Biological station, and combined long days in the lab studying material collected throughout the project with shorter trips out on R/V Hans Brattstrøm.

Here we collected live colonies, introduced the students to various collecting methods, and let everyone catch some fresh fjord air.

Tine (top left) working together with Mali in the lab and in the field.

Tine is doing her master thesis on the species distribution of Bryozoa in shallow water along the Norwegian coast.

During the workshop she got the chance to have some of the difficult species identifications verified by the experts, and she prepared a plate of 95 tissue samples that will be DNA barcoded though NorBOL.

Tiril, top left, together with Jon on the ship and working in the lab.

We also had Tiril with us, who is just starting out on what will become a thesis on ascidians (sea squirts), most likely with a focus on species in the genus Botryllus and Botrylloides.

She worked together with Tom, getting familiar with the literature and the methods used for working on the group. Like Tine, she will be using a combination of traditional morphology based methods and genetic data.

A few impressions from the week

Going forward we’ll first send the plate of tissue samples to CCDB to be sequenced, fingers crossed for good results! During the week, *so many* samples were identified, so we will certainly be preparing more plates during the spring. All the identified samples will be included into the scientific collections of the museum.

Thank you so much to all the participants for their efforts!

-Katrine