From the 13th to 20th of October, we were on fieldwork again! This time the end destination was Sletvik field station. Sletvik field station belongs to the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim (NTNU). The team of NorDigBryo (digitization of Norwegian Bryozoa) had organized a workshop there and team snail was invited to tag along for the opportunity to collect some snails around the area. So there the three of us traveled from Bergen up North; Jon and Katrine for the Bryozoan workshop and me for the Lower Heterobranchia and Pyramidellidae project.

The travel from Bergen to Trondheim takes more than 10 hours! For such a long travel we of course needed to take several breaks throughout the day. But with a bunch of biologists on the way it was very difficult to not sample during those stops whenever we had the opportunity (1).

1. Sampling on our way, together with Jon & Katrine visiting several harbors. Photo: Cessa Rauch, UiB.

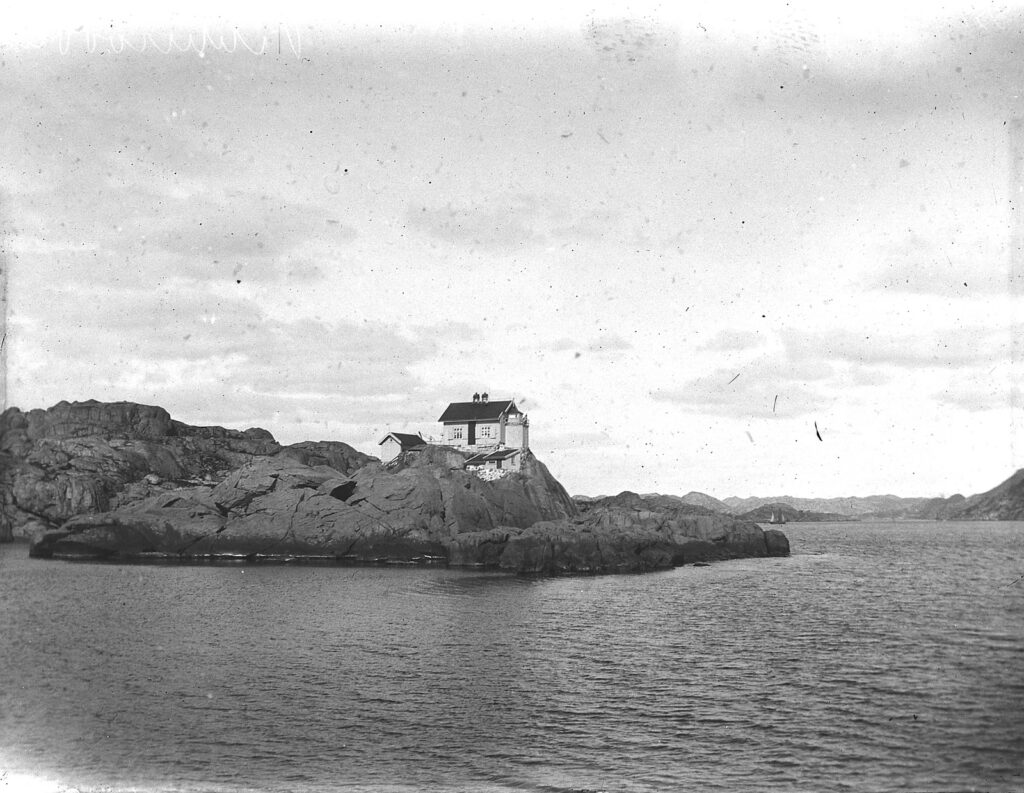

After a very long day, we finally arrived at our end destination; Sletvik field station. This would be our home for the coming week. The station has great facilities with different laboratories, a cantina with 3 meals a day being served by the kitchen staff and sleeping facilities. There is space for up to 40 students, so with just 10 of us we had a ton of space (2).

2. The Sletvik field station from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim (NTNU). Photo: Cessa Rauch, UiB.

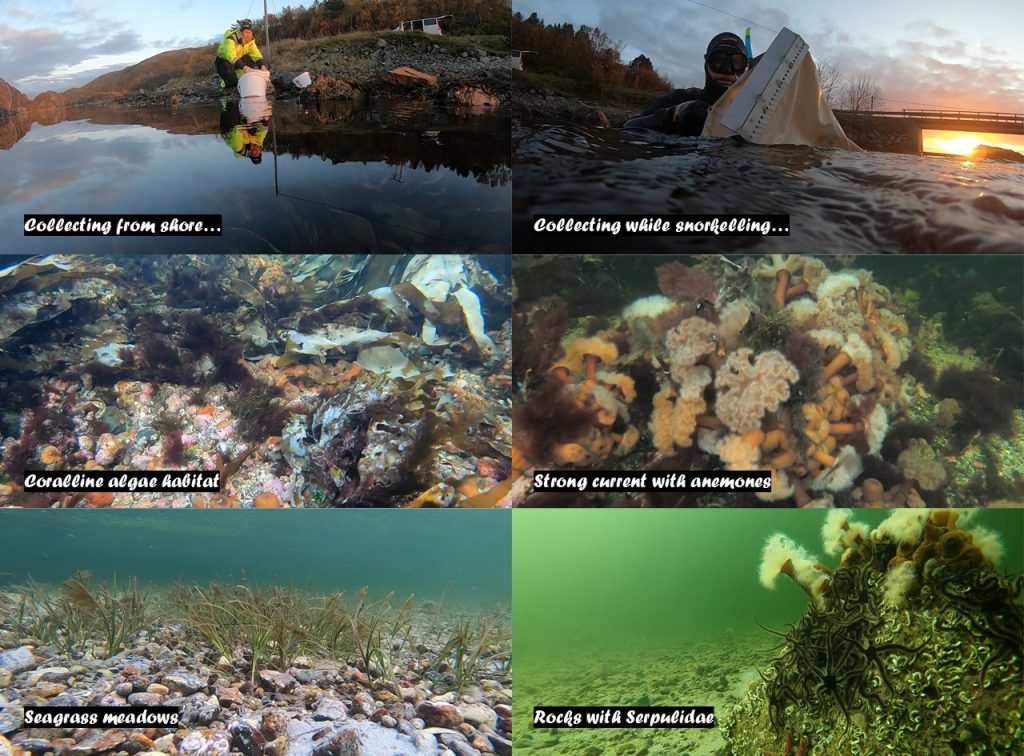

The Sletvik field station is located on the small peninsula called Slettvik; surrounded by mostly water makes it an excellent location for marine related fieldwork. Despite the relatively small size of the peninsula, it has a surprising number of different habitats; there are seagrass meadows, sea bottoms covered in encrusting coralline algae and due to strong tidal currents, a very vibrant and diverse marine life (3).

Therefore, we used several days that week to collect fresh material from around the area: by using nets or hands either from land or while in the water snorkeling (4).

4. Snorkeling for samples in strong tidal current right under the little bridge, with Jon and Cessa. Photo Katrine Kongshavn, UiB.

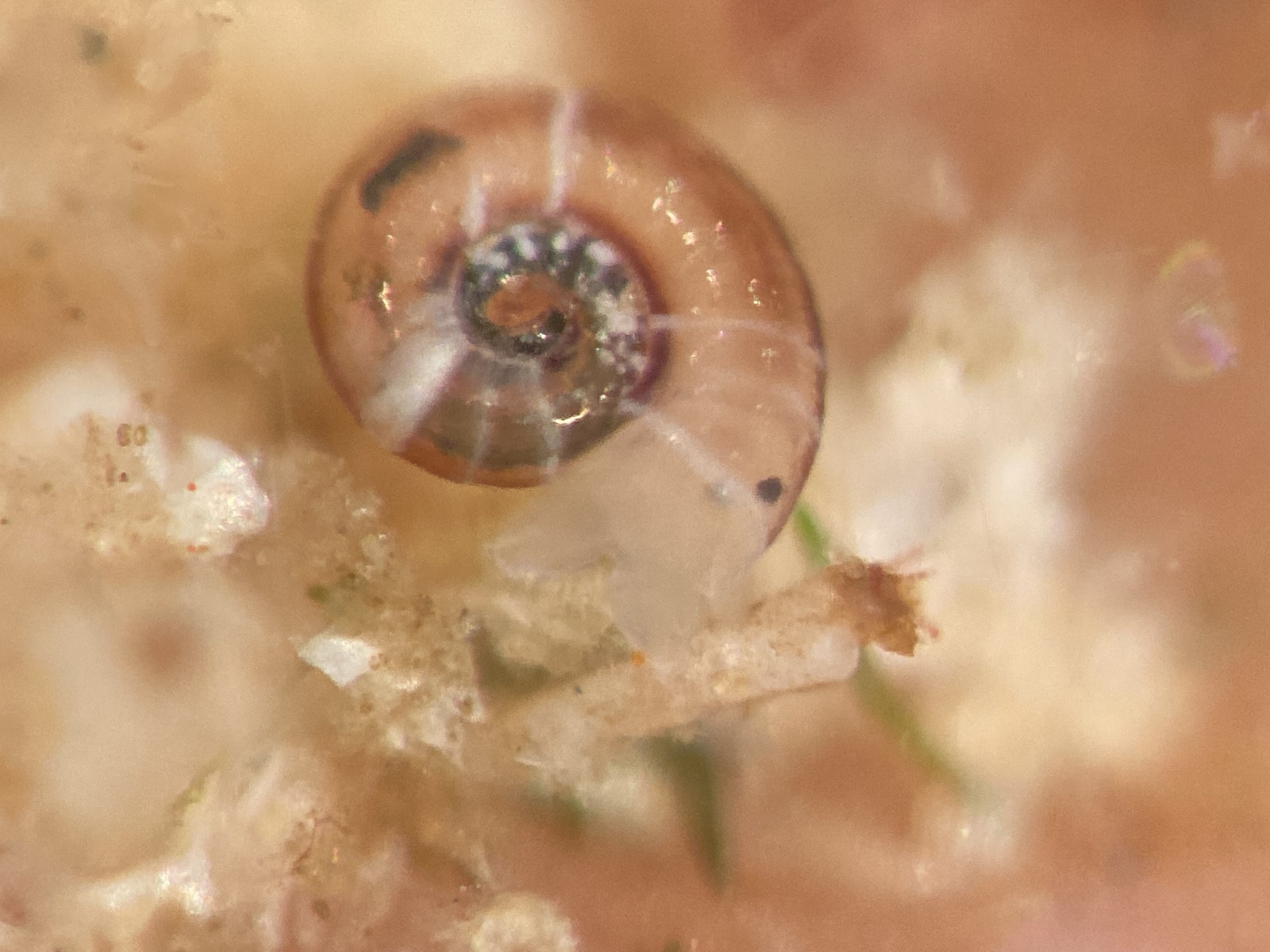

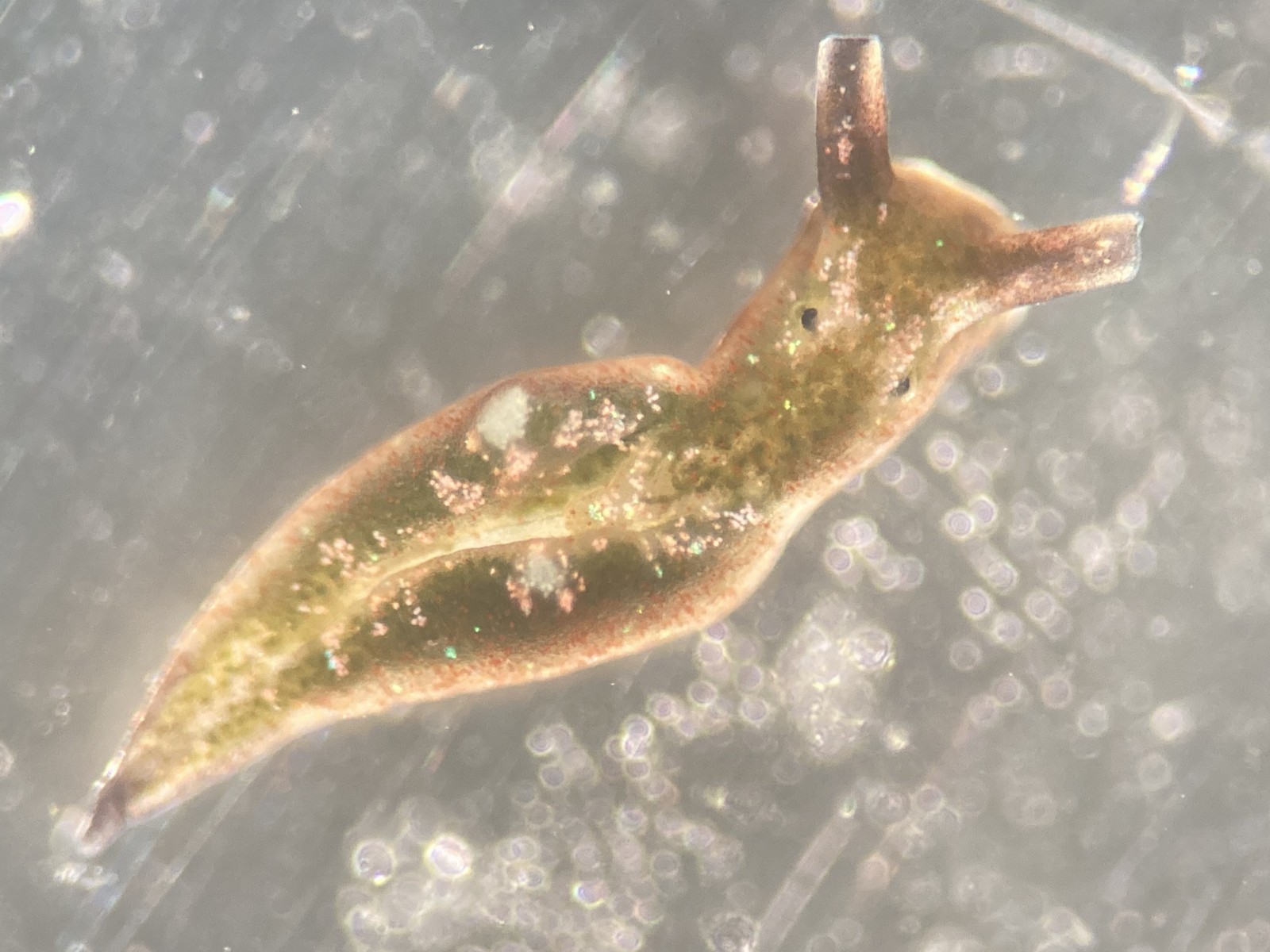

The strong tidal currents are what a lot of the Pyramidellid species absolutely love! Not the least because it attracts high diversity of their hosts that they parasite on (5). Places with lot of current have large influx of nutrients and are well oxygenated which often results in high diversity, such as the well-known Saltstraumen area in Nordland. Therefore, it was easy to collect them as the snails were so abundant.

5. Hard to spot the small snails, here Odostomia turrita (blue circle) crawling away from its host Serpullid worm (white with blue fringes). Photo: Cessa Rauch, UiB.

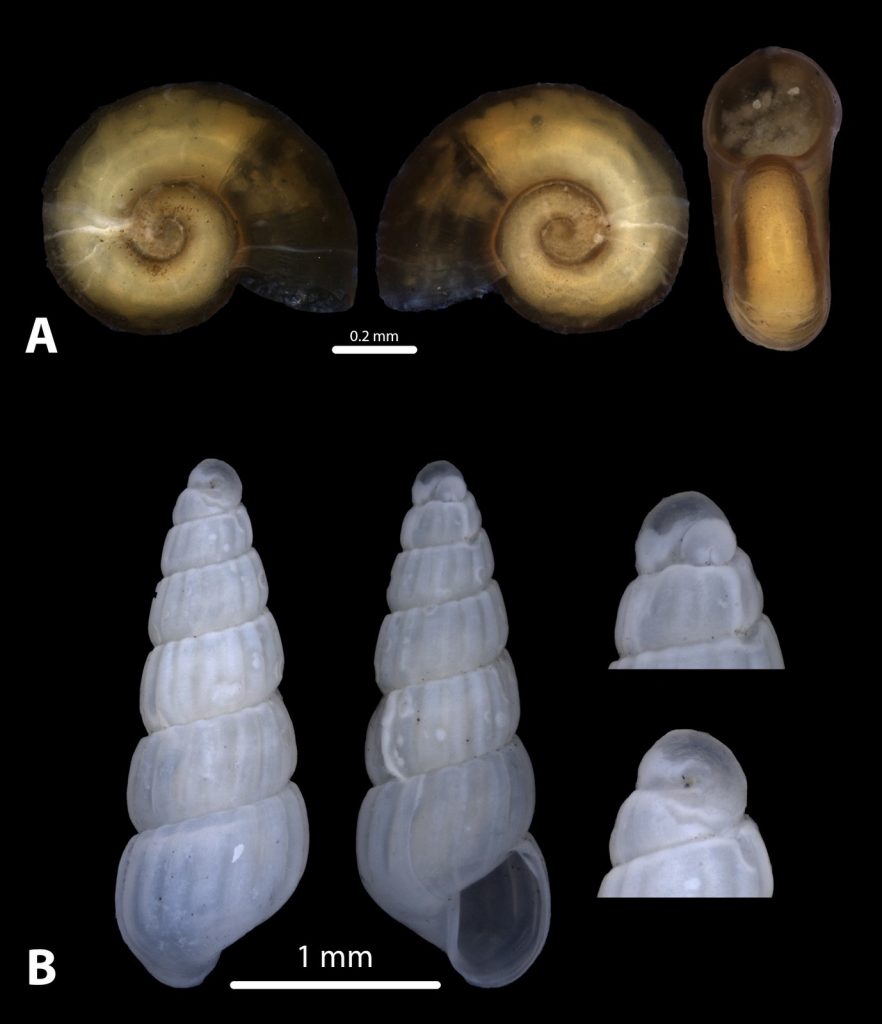

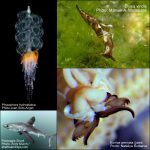

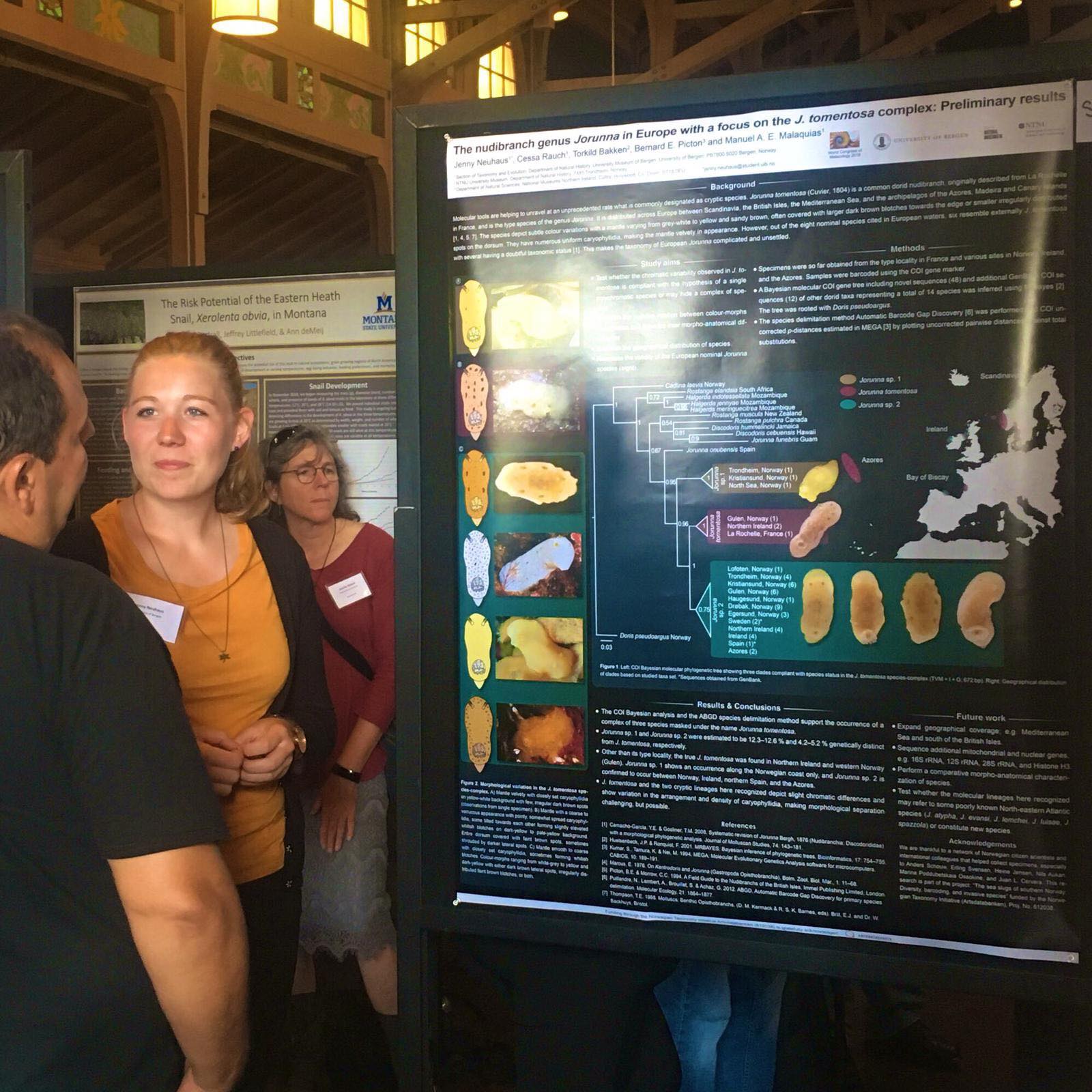

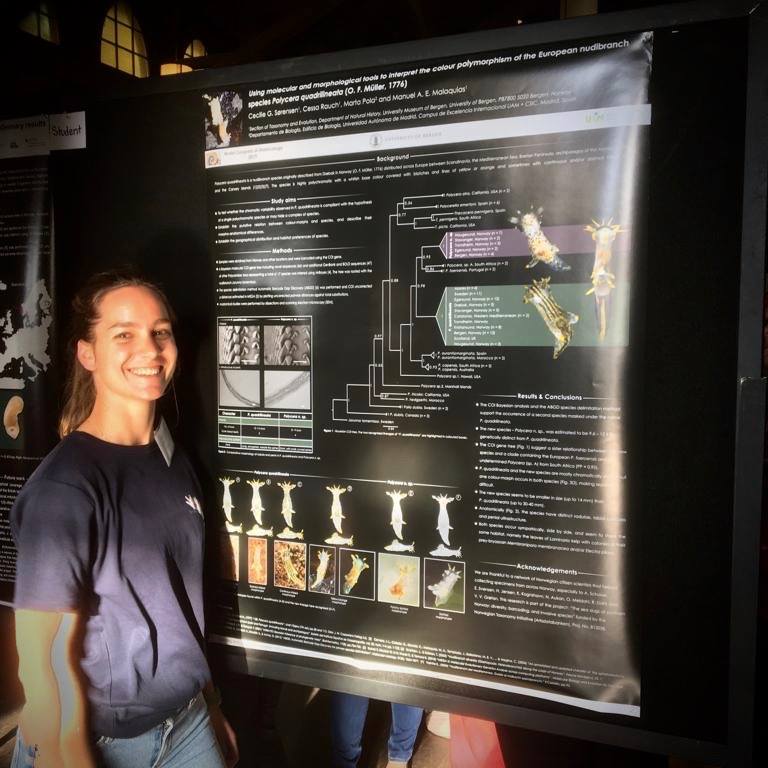

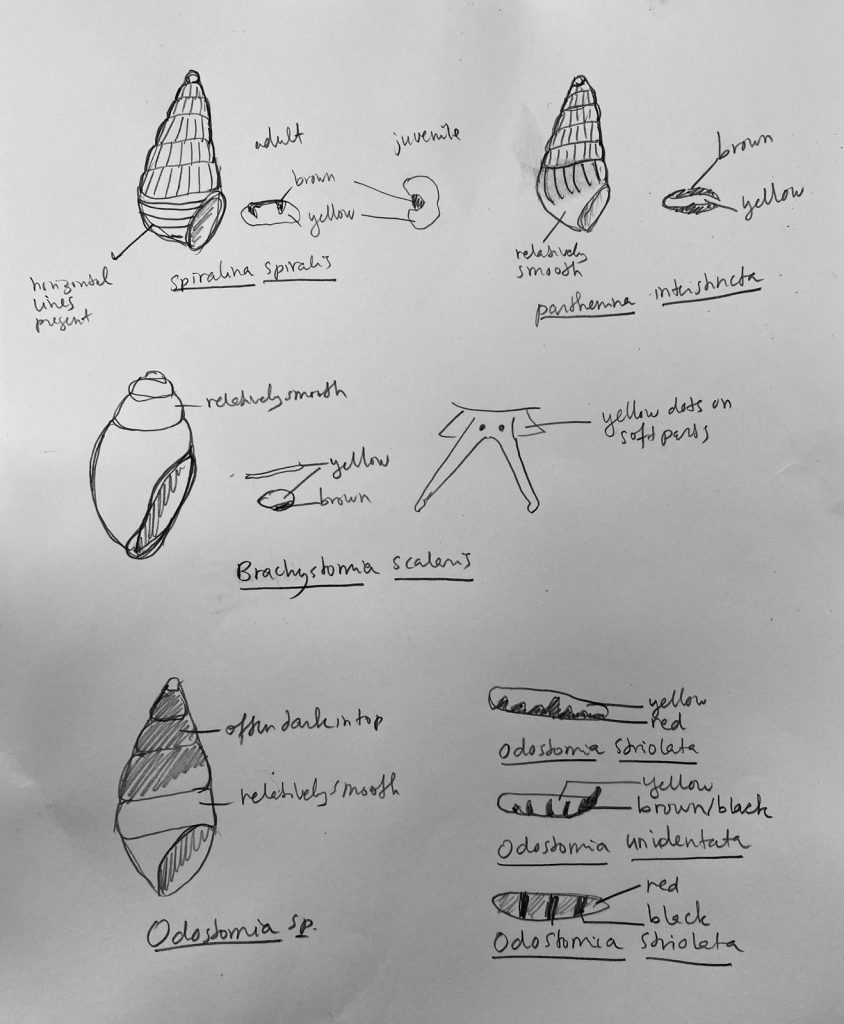

But it became clear quickly that a few species were quite dominant. The four most common Pyramidellid species in the shallow tidal currents around Sletvik were Odostomia turrita; Brachystomia scalaris; Spiralina spiralis and Parthenina intersincta (6). Although Pyramidellidae snails are often very difficult to identify, these fours exhibited very typical characteristics which made it somewhat easy to name them to species level (7).

6. 4 of the most common species found in Sletvik: Left up; Odostomia turrita, left down; Brachystomia scalaris, right up; Spiralina spiralis, right down; Parthenina intersincta. Photo: Cessa Rauch, UiB

7. Doodles of the most recognizable characters of different common species in Sletvik. Photo: Cessa Rauch, UiB.

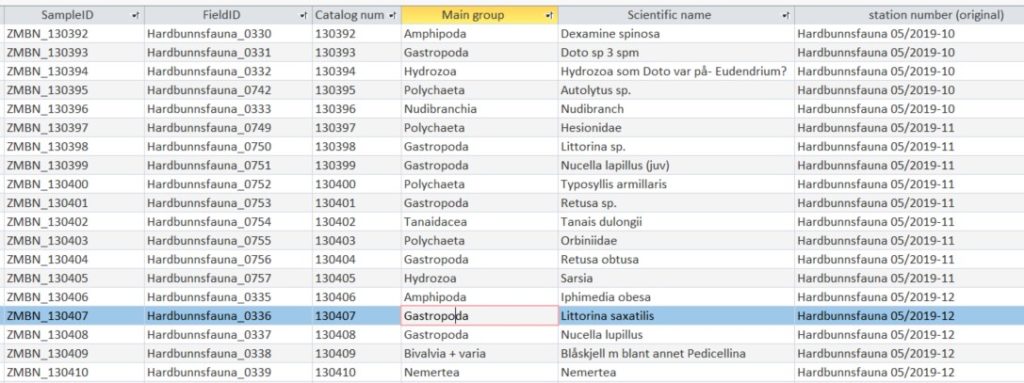

However, we still will extract DNA from these animals to confirm species, as it still can happen that we are having snails that are very similar and might have been misidentified in the field. That is why it is important to fix the collected snails in ethanol, so the tissue and DNA in it stays preserved. All collected material will then go back to the University Museum of Bergen to be further used for microscopy, morphological analysis, DNA extractions and eventually become part of the collection of the museum.

After one week, with hours of sorting through collected material, we managed to collect and identify 15 different species; the most so far of any fieldwork so we can say that Sletvik is truly a snail heaven!

– Cessa