Two weeks ago I had the chance to go field-sampling on the research vessel Hans Brattström. The sampling this time was focused on a broad range of marine invertebrates ranging from Hydrozoans, Bryozoans, Polychaetes, Phoronids and Brachiopods. I was especially on the hunt for polyps of the family Hydractiniidae (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) that grow preferably on shells of molluscs or hermit-crabs. I was happy to look for new specimens for NorHydro and my master’s project, especially since opportunities to go field-sampling have been rare due to the covid-19 restrictions. The area of Bergen has been sampled quite well for the NorHydro project, but I was especially looking for rare species or species that haven’t been sampled before.

The first sampling for NorHydro this season – and with great conditions! Picture Credit: Lara Beckmann

To collect hydractiniids, we took bottom samples using a triangular dredge and a grab sampler. When the dredge gets back on board, the sample gets sorted on a large table on deck. Then the detailed search begins, and every stone and cranny gets inspected. The polyps I was looking for can be tiny, ranging from less than 1 mm up to 8 mm. The substrates that they grow on vary in size and shape, it can be crabs, molluscs but also algae or stones, often not larger than a few centimeters. So it isn’t an easy task to find the polyps in a freshly collected sample. Luckily I found several conspicuous hermit crabs and also one snail that I took back to the museum. At first, I didn’t see the polyps – only under the microscope in the museum laboratory I was able to see that hydractiniid colonies were growing on the shells.

Video: A polyp colony of the species Podocoryna areolata (Family Hydractiniidae). The polyps were growing on the shell of a living mollusc, probably of the species Steromphala cineraria. Video Credit: Lara Beckmann

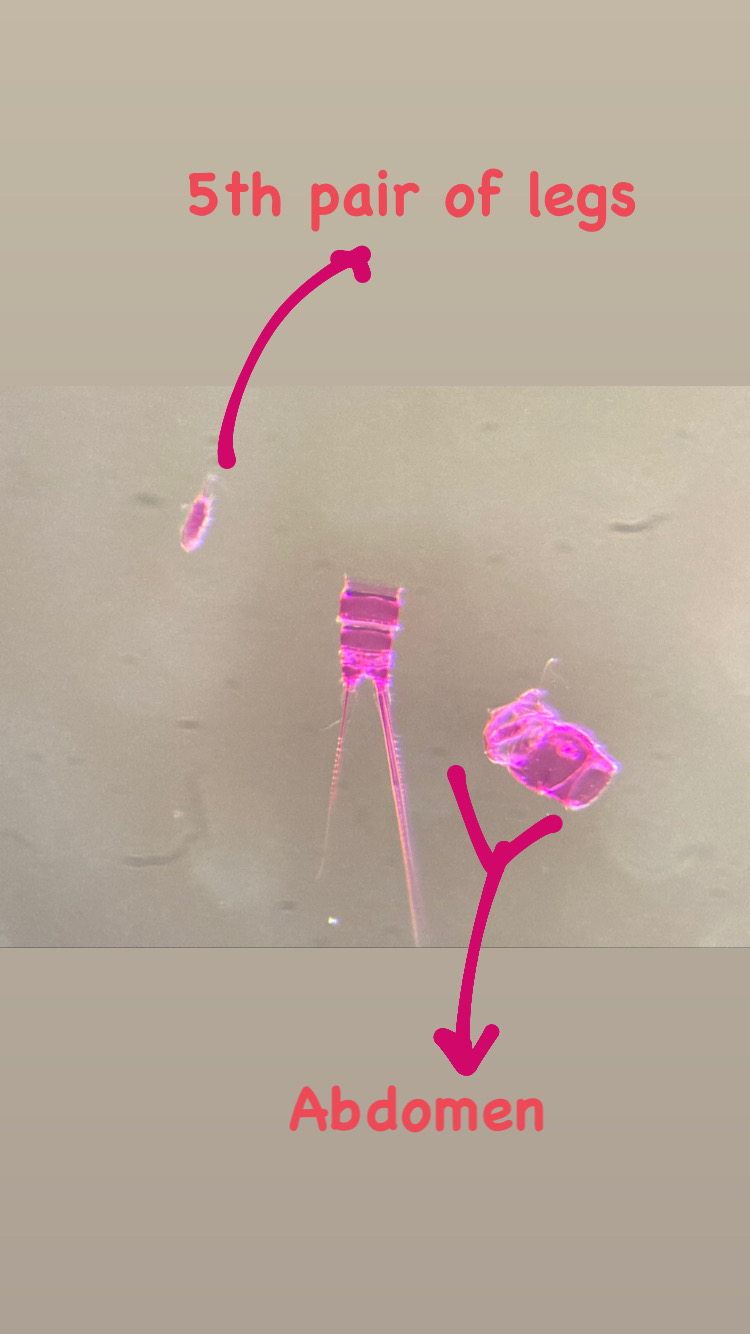

One colony of the species Podocoryna areolata was growing on the shell of a living mollusk. The mollusk provides a nice substrate because the movements of the snail provide the polyps with more opportunities to encounter food. Also, the colony is protected by the small wrinkles of the shells surface where the polyps can hide. The polyps of this species are super difficult to measure, but most are smaller than 0.5 mm. When disturbed, the polyps shrink to small blobs even smaller than this. When relaxed, they can extend a bit longer in size. Especially the tentacles reach out to get hold of any potential food that swims by, such as small crustaceans. This species releases medusae, which can frequently be found in the plankton in this area.

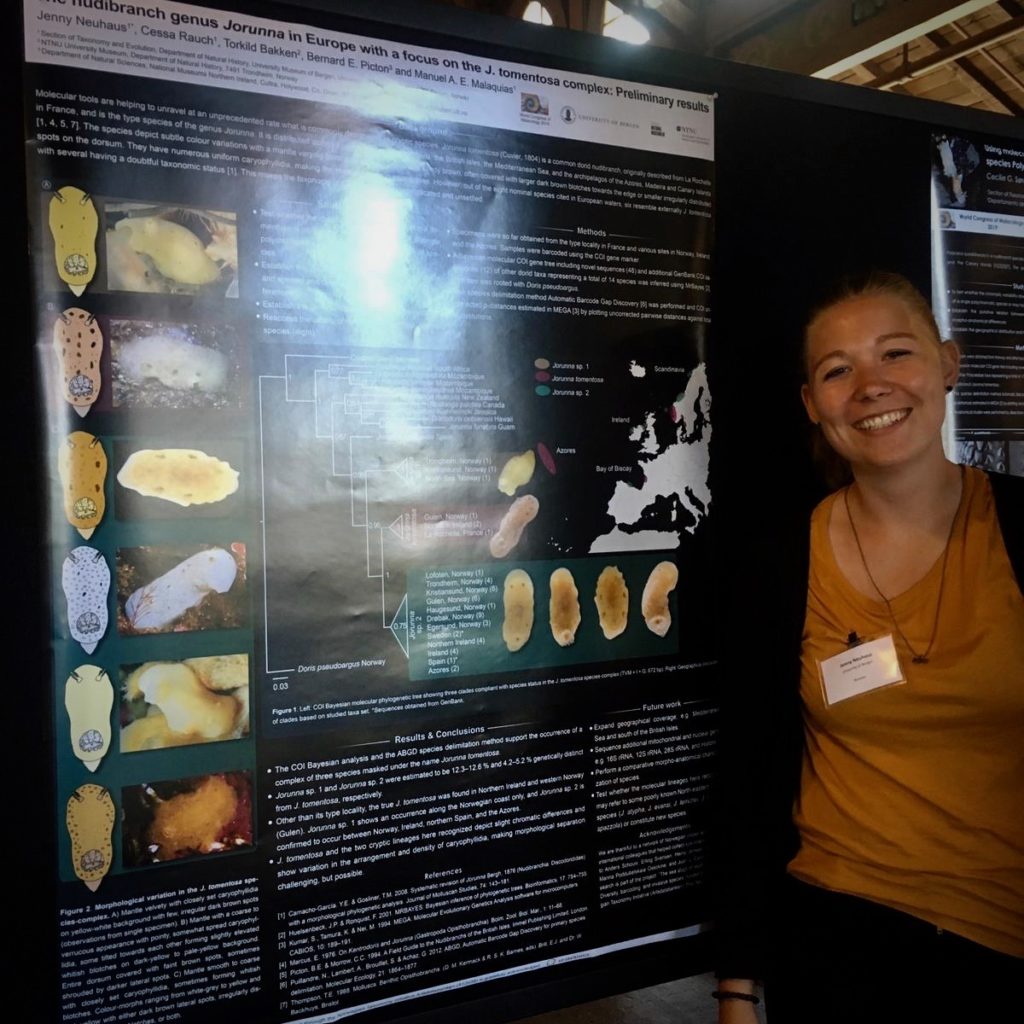

On shells inhabited by hermit crabs of the species Pagurus bernhardus, I found several colonies of a yet unidentified species of the genus Podocoryna. This species is very commonly found as polyp almost along the entire Norwegian coast. I’m still studying the specimen to figure out the correct identification. Since there is a lot of confusion in the hydractiniid taxonomy, I need to combine genetic information and morphology to overcome the existing problems in their identification and naming. The colony was reproductive and medusa buds were growing on it. Interestingly the medusa of this species is rarely found in the plankton.

Polyps of the genus Podocoryna. On the right are parts of the grasping claws visible belonging to the hermit crab Pagurus bernhardus. Picture Credit: Lara Beckmann

All over the colony were medusa buds. These are growing medusae, which will be released in the water when they are mature. The medusae can do what the colony itself can’t: releasing eggs and sperm and thus reproduce sexually. Picture Credit: Lara Beckmann

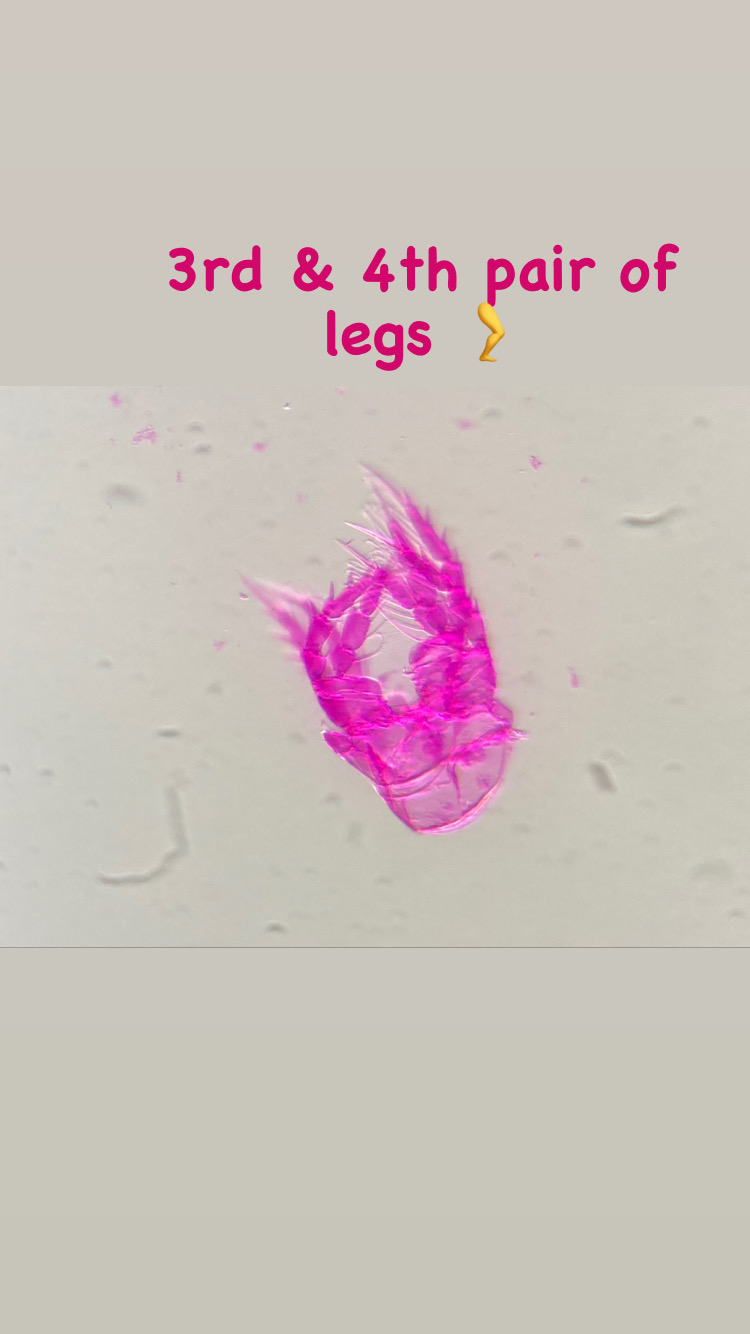

Besides the polyps, I found several other organisms living with the colonies on the shells including Crustaceans, Nudibranchia, Foraminiferans and other hydroids. The shells provide a home for a diverse range of marine life and it resembles a tiny forest. But it is not all peace and harmony in there, the smallest amphipods were quickly munched by the Podocoryna polyps. Those, in turn, get eaten by nudibranchs, that crawl on the colonies and some species feed specifically on hydroid polyps.

Video: An amphipod that lives on top of the hermit crab shell, walking through the colony of Podocoryna polyps. Video Credit: Lara Beckmann

I didn’t find any more hydrozoan species that were interesting for NorHydro during the sampling trip (at least not while scanning with the bare eye). But, I want to show one more very common species around Bergen –Ectopleura larynx– just because it is such a nice-looking hydrozoan. It even was reproductive and released its larvae right into my petri-dish. The small bulbs that grow between the polyp tentacles contain the larvae, which are called actinula. They break free and swim around, swinging their tiny tentacles until they will settle on a piece of algae for example, and grow to a large colony again.

The species Ectopleura larynx is a common species at the Norwegian coast. On the left the released larvae, called actinula. On the right a polyp that usually grows in a large colonies with up to a hundred polyps. Picture Credit: Lara Beckmann

-Lara

You want to learn more about hydrozoans and why it is important to study them? Read more about it in my blog article for Ecology for the Masses: link.

Also, keep up with the activities of NorHydro here in the blog, on the project’s facebook page and in Twitter with the hashtag #NorHydro.