Guest researcher: Eric

Eric, from the Federal University of ABC, visited the University Museum in November. We asked him about his time in Bergen examining some of the least common species of siphonophores in the collections and this is what he told us:

My name is Eric Nishiyama, and I am a PhD student from Brazil. The main focus of my research is the taxonomy and systematics of siphonophores, a peculiar group of hydrozoans (Cnidaria, Medusozoa) notorious for their colonial organization, being composed of several units called zooids. Each zooid has a specific function within the colony (such as locomotion, defense or reproduction) and cannot survive on its own.

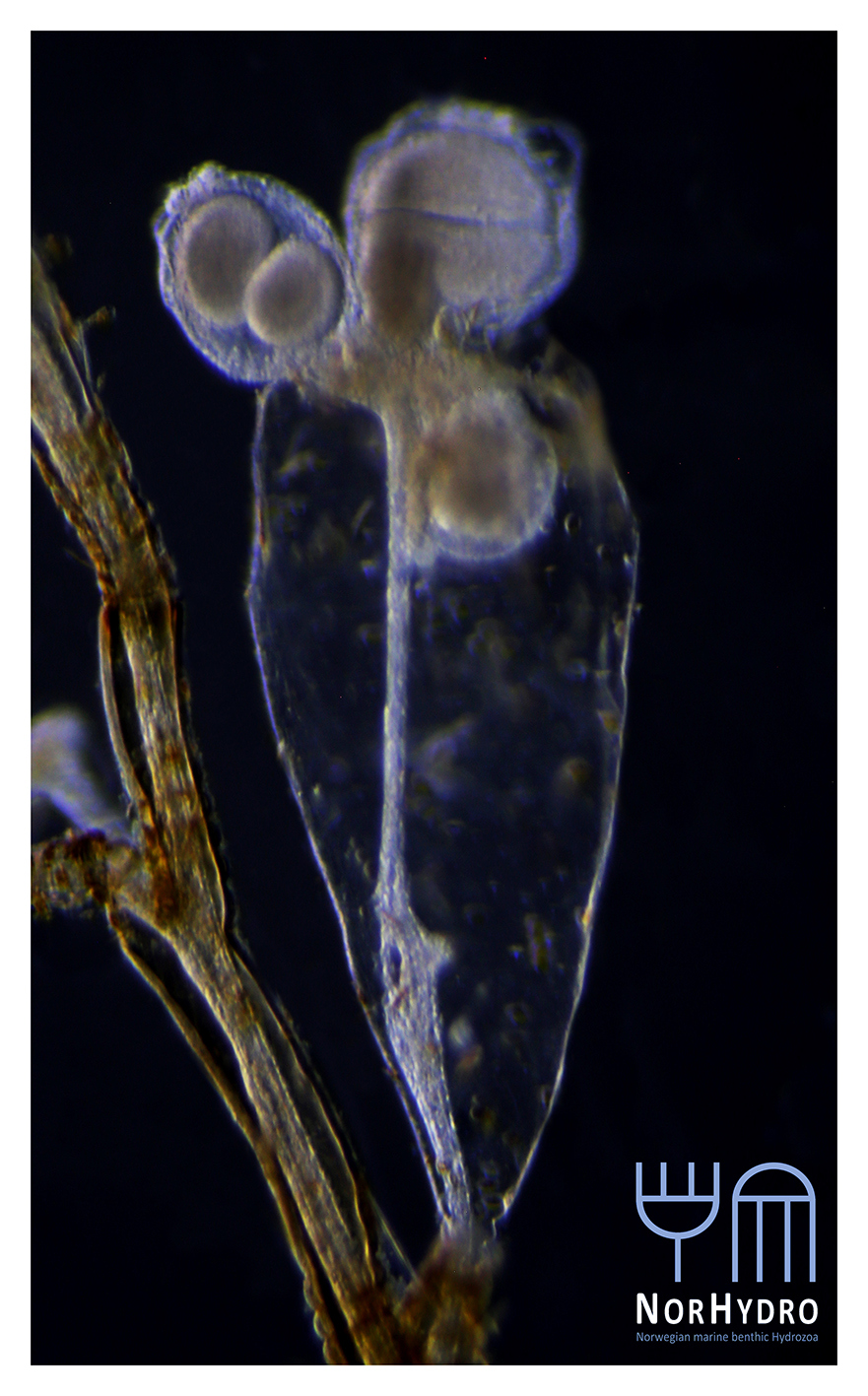

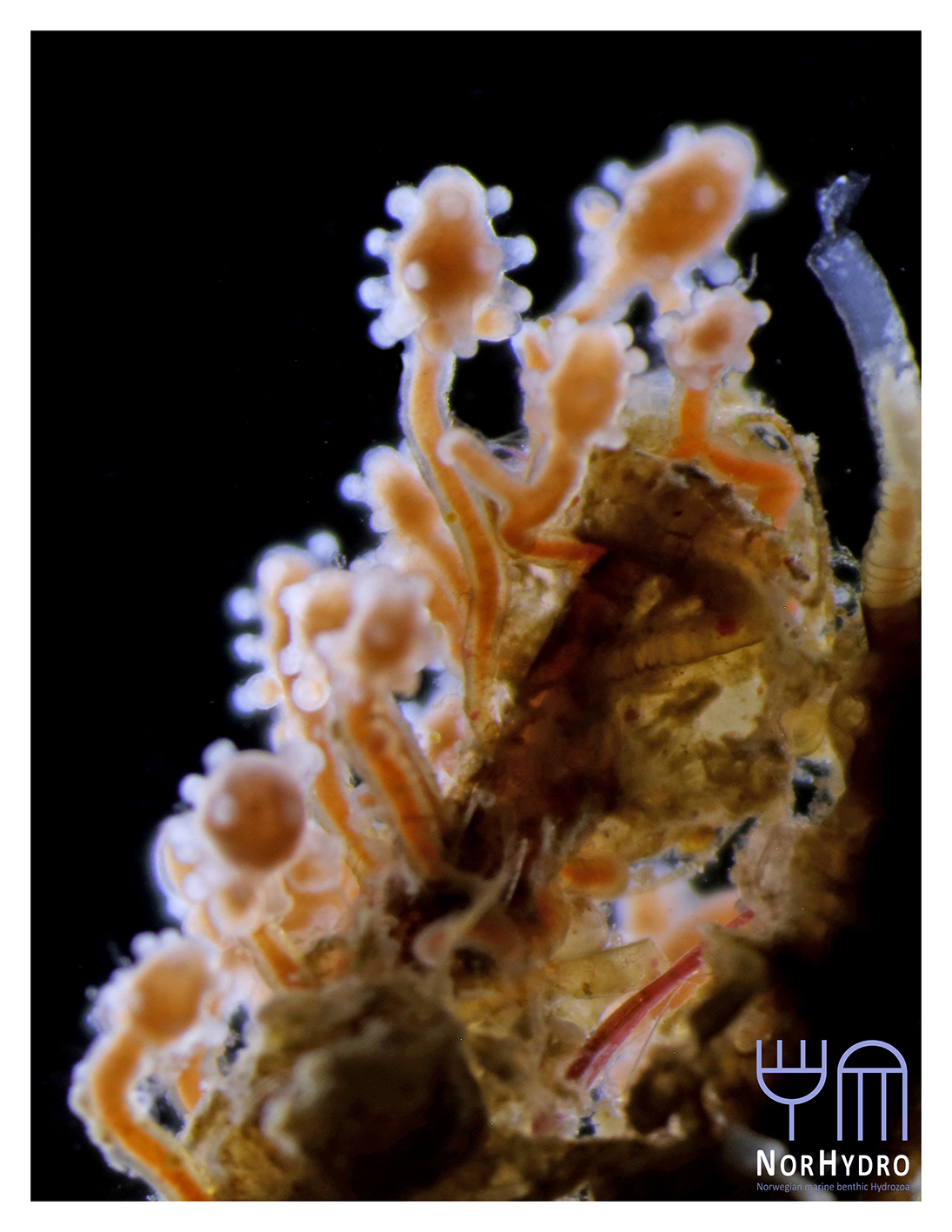

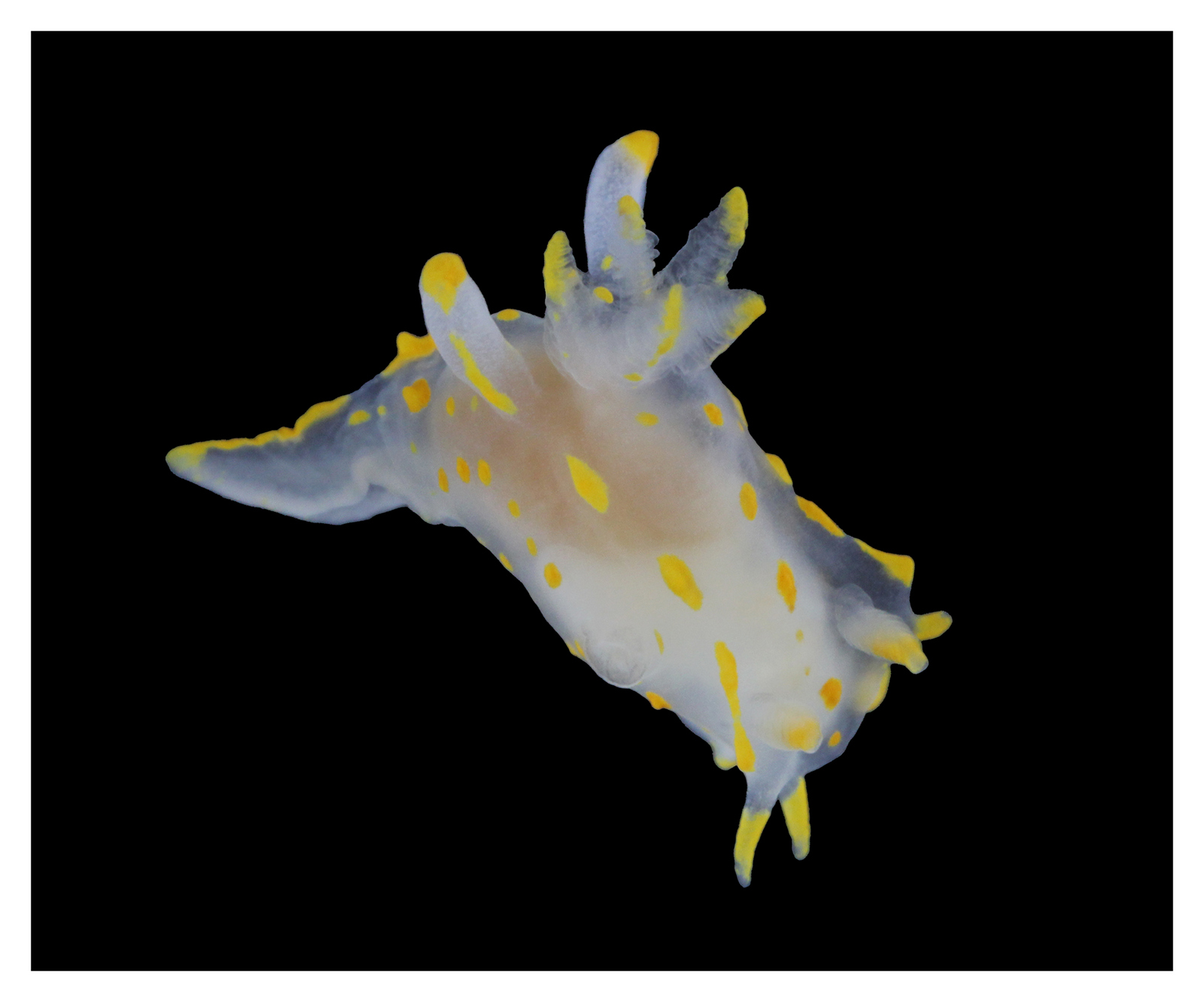

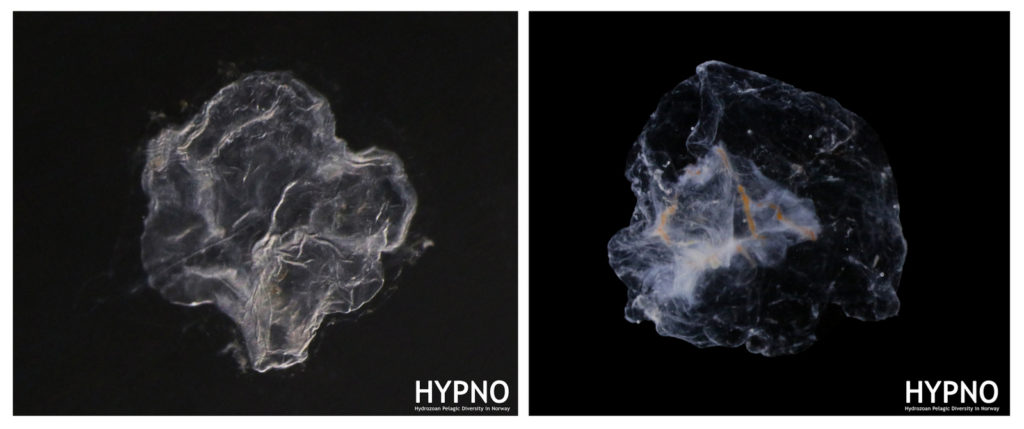

Fig_1. I had the opportunity to examine both ethanol- and formalin-fixed material from the museum. For morphological analyses, specimens preserved in formalin are preferable because ethanol-fixed individuals are usually severely deformed due to shrinkage.

Understanding how zooids evolved could provide major insights on the evolution of coloniality, which is why I am looking at the morphology of the different types of zooids. In this sense, siphonophore specimens available at museum collections provide valuable information for visiting researchers such as myself.

During my short stay at the University Museum of Bergen in November, I was able to examine a few siphonophore samples deposited at the museum’s collections. By examining the specimens under a stereomicroscope, and using photography and image processing tools, I was able to gather a lot of information on the morphology of several species.

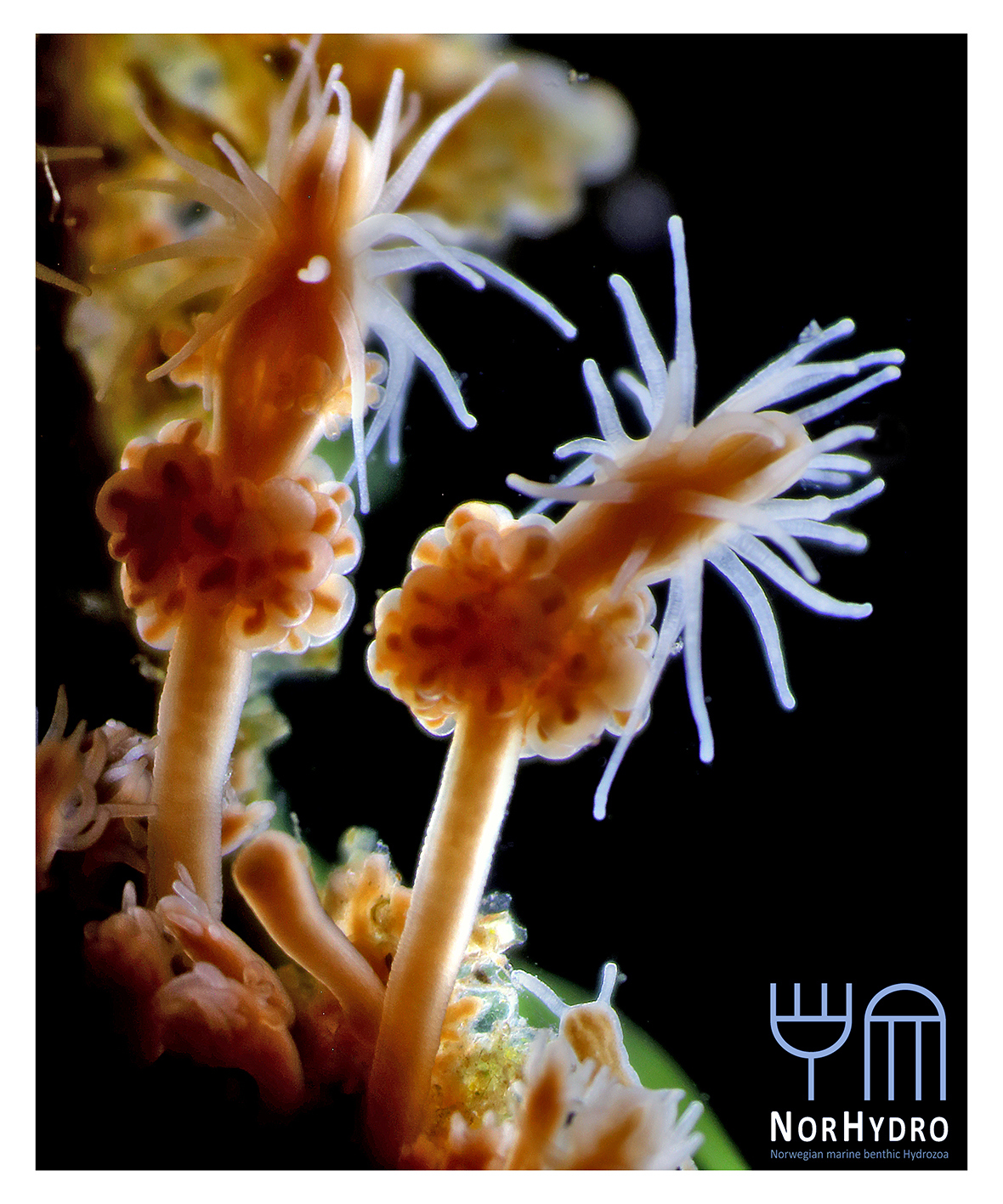

Fig_2. Documenting the morphology of the nectophores of Rudjakovia plicata (left) and Marrus or-thocanna (right) was particularly interesting because these species are not commonly found in museum collections.

Fig_3. Other ‘unusual’ siphonophores that I was able to examine were Crystallophyes amygdalina (left) and Heteropyramis maculata (right).

The data obtained will allow me to score morphological characters for a phylogenetic analysis of the whole group, and hopefully will help me revise the group’s taxonomy.

– Eric

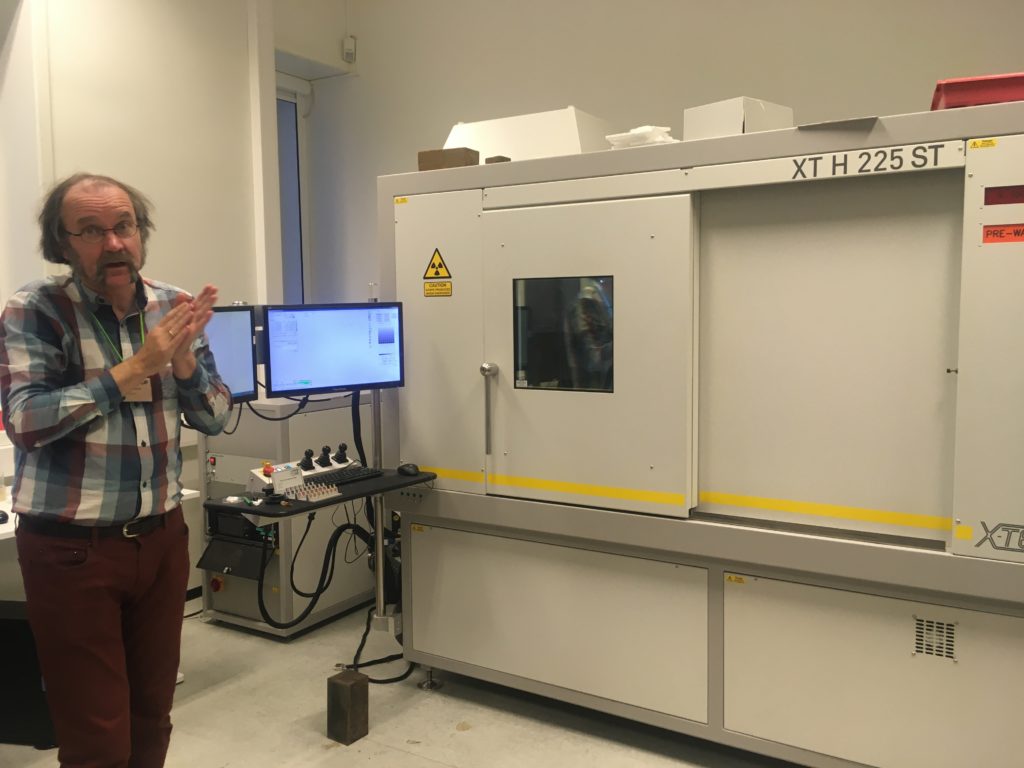

CT scan all the things!

Oslo Natural History Museum 02.12.2019 – 06.12.2019

From December 2 till December 6 Justine Siegwald, Manuel Malaquias and I (Cessa) attended a CT scanning course in Oslo at the Natural History Museum.

The course was organized by the Research School in Biosystematics (ForBio) and Transmitting Science.

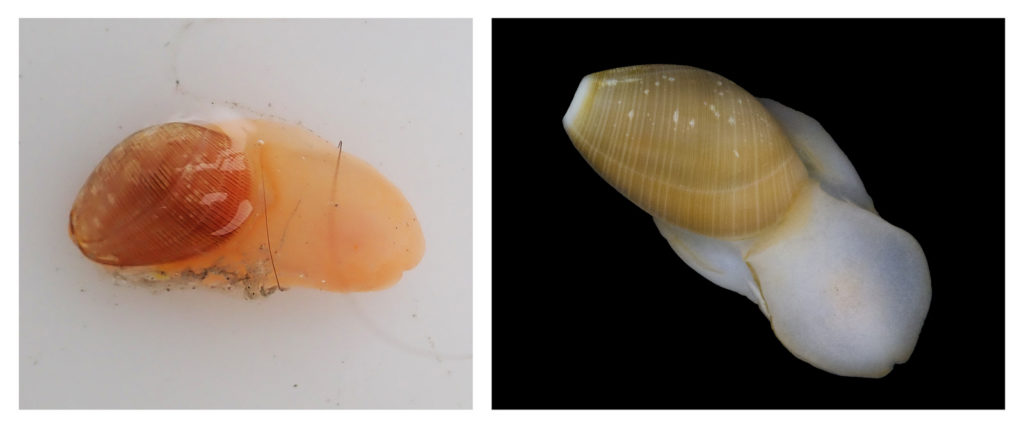

The three of us all work on mollusks and one of the main reasons to deepen ourselves in CT scanning techniques is because of studying the internal anatomy of these often small and delicate specimens.

Species descriptions are not only based on external morphology and/or DNA barcoding, a lot of the species differences are small details within the internal structures. Like the reproductive organs and digestive system (e.g. radular teeth) of the animals. This is very laborious work, and can be challenging especially with the smaller specimens of only a few millimeters long. Besides some species are difficult to collect and can be a rare collection item of the museum. Once you cut these animals to study them, there is no turning back and the specimen is basically destroyed. Being able to see the insides of the animal without touching it would therefore be ideal. CT scanning comes very close to that and with powerful X-ray we can almost see every detail of the insides of the animals without the need to cut them open

However, how easy as this sounds, CT scanning soft tissue comes with some challenges. Soft tissue means that the x-ray contrast is often very low. Even with modern good x-ray detectors it is still difficult to detect the different internal structures. Therefore, during the course, we were taught how to artificially increase the contrast of the tissue by staining the specimens before mounting them in the CT scan machine.

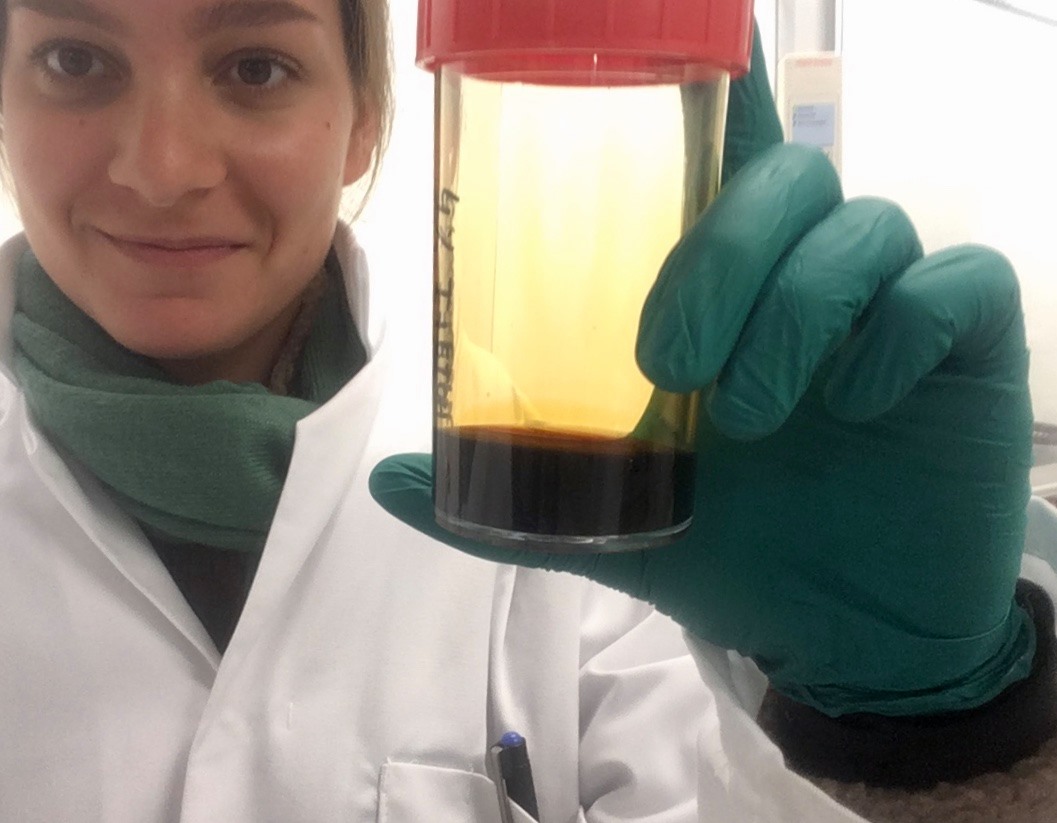

Coating a specimen with a metal (e.g. gold or platinum) is only useful if you want to see external details of the study object, coating will not help revealing internal structures. For radio contrasting the internal anatomy, you can stain specimens with high density liquids like iodine to enhance the x-ray contrast. So, we went for this option and left our specimens in iodine ethanol solution overnight

- Preparing the iodine solution

- Sea slug in iodine solution

After the staining process, we needed the wash out any extra iodine before mounting the specimen into the CT scan. A good scan is not simply pressing the button of the machine; there are a bunch of settings that can be adjusted accordingly (e.g. tube voltage, tube current, filament current, spot size, exposure time, magnification, shading correction, etc.). The scan itself can take hours and file sizes of 24GB for a single object are not uncommon, which means you need a powerful computer with decent software to process this information. Part of the course was also about how to visualize and analyze the files of the CT scan with software like Avizo

Video 1. Software Avizo has a user-friendly interface for analyzing all sorts of CT scanning files.

The week gave us some very promising first results (se video below), and also new insights about how to increase the X-ray contrast of our sea slug samples (lots of hours of staining and very short washing steps).

Video 2. 3D reconstruction of one of Justine’s shell samples

It was a very fruitful week and besides interesting new ideas for scanning our museum specimens, we also met many old and new friends during the week that was as inspiring. ForBio and Transmitting Science did a really great job with setting up this course and I can highly recommend it to anyone who is interested in CT scanning.

Explore the world, read the invertebrate blogs!

-Cessa

Field season’s end

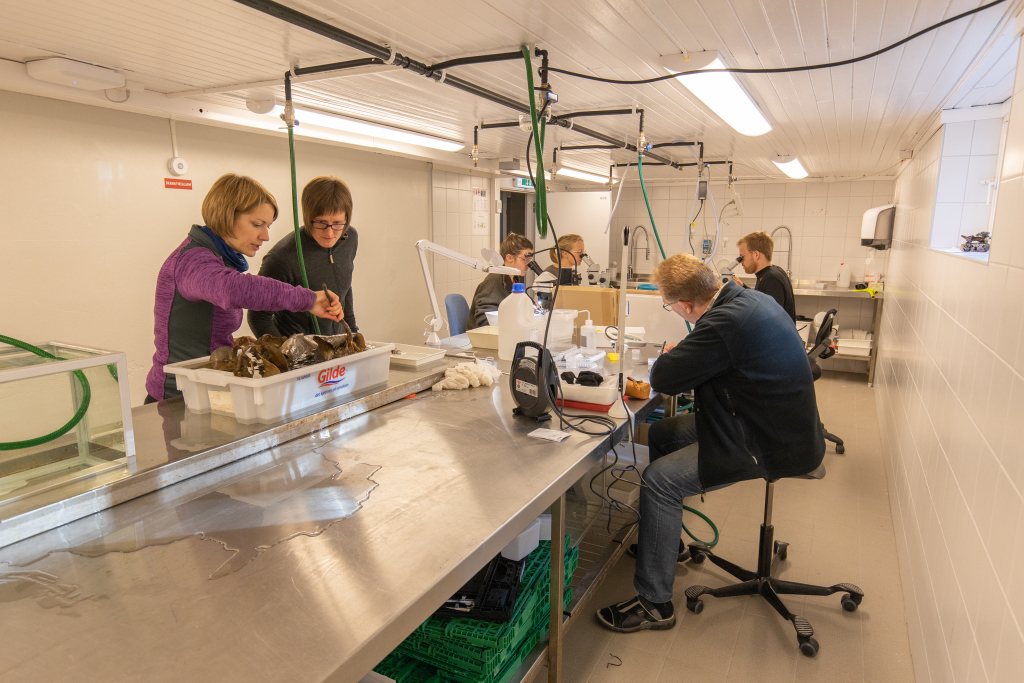

Sletvik field station, October 15th-23rd 2019

- Sletvik field station, Agdenes

We wanted to make a write-up of the last combined fieldwork/workshop we had in 2019, which was a trip to the marine field station of NTNU, Sletvik in Trøndelag, in late October. From Bergen, Luis (NorHydro), Jon, Tom, and Katrine (Hardbunnsfauna) stuffed a car full of material, microscopes, and drove the ~12 hours up to the field station that we last visited in 2016. Beautiful fall in Trøndelag

Beautiful fall in Trøndelag

There we joined up with Torkild, Aina, Karstein, and Tuva from NTNU university museum, students August and Marte, and Eivind from NIVA. We also had some visitors; Hauk and Stine from Artsdatabanken came by to visit (if you read Norwegian, there’s a feature about it here), and Per Gätzschmann from NTNU UM dropped by for a day to photograph people in the field.

During a productive week the plan was to work through as much as possible of the material that we and our collaborators had collected from Kristiansand in the South to Svalbard in the North. Some of us went out every day to collect fresh material in the field close to the station.The Artsprosjekts #Sneglebuss, Hardbunnsfauna, NorHydro, and PolyPort gathered at Sletvik, and with that also the University museums of Trondheim and Bergen. Of course we were also collecting for the other projects, and the museum collections.

- The littoral zone was teeming with biologists (and some invertebrates). Photo: Per Gätzschmann, NTNU

- Busy lab, where we were sorting the fresh samples Photo: Per Gätzschmann, NTNU

- Photo: Per Gätzschmann, NTNU

- Luis in the field, showing a catch of hydroids. Photo: Per Gätzschmann, NTNU

- A squat lobster that would not let go of the red gloves before having its picture taken Photo: K. Kongshavn

- The great Littorina escape; Sletvik edition – we found them all over, as usual. One managed to clog a sink enough to cause a minor flood – that’s when it is good to be in a wet lab.

One of the things Hardbunnsfauna wanted to do whilst in Sletvik was to pick out interesting specimens to submit for DNA barcoding. This means that the animals need to be sorted from the sediment, the specimens identified, and the ones destined to become barcode vouchers must be photographed and tissue sampled, and the data uploaded to the BOLD database. We managed to complete three plates of gastropods, select specimens for one with bivalves, and begin on a plate of echinoderms, as well as sort through and select quite a few crustaceans and ascidians for further study.

- Photolab – trying to convince the amphipods to stand still so we can capture their colours Photo: K. Kongshavn

- Some seaweed to cling to helps

- Many of the gastropods were truly *tiny*, the scale above shows millimeters

- Aina did a fantastic job persuading tissue samples out of the shells of the (mostly minute) snails, and filling the three plates with tissues samples.

- Samples for barcoding

- We also managed ~half a plate of echinoderms, we’ll fill the rest as we go through more material

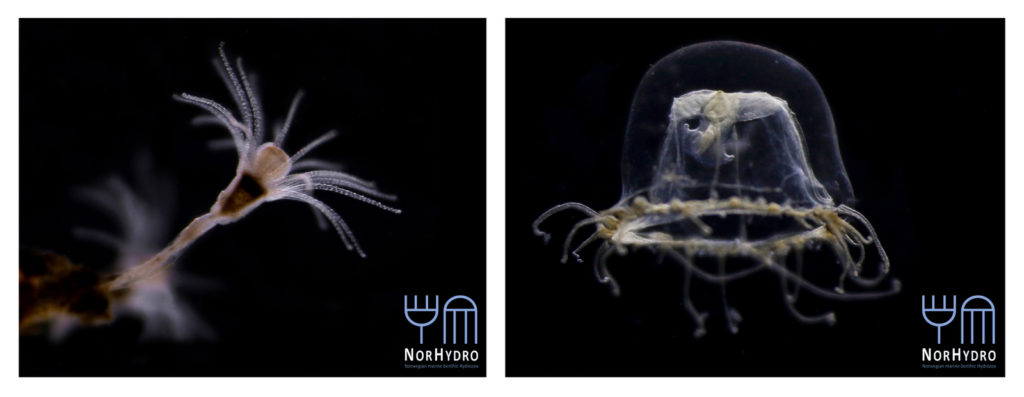

Collecting some fresh material was particularly important for NorHydro because the hydroids from the coasts of Trøndelag have not been thoroughly studied in recent years, and therefore we expected some interesting findings in the six sites we managed to sample. We selected over 40 hydrozoan specimens for DNA barcoding, including some common and widespread hydroids (e.g. Dynamena pumila), some locally abundant species (e.g. Sarsia lovenii) and exceptionally rare taxa, such as the northernmost record ever for a crawling medusa (Eleutheria dichotoma). We also used a small plankton net to catch some of the local hydromedusae, and found many baby jellyfish belonging to genus Clytia swimming around the field station.

- Dynamena pumila. Photo: L. Martell

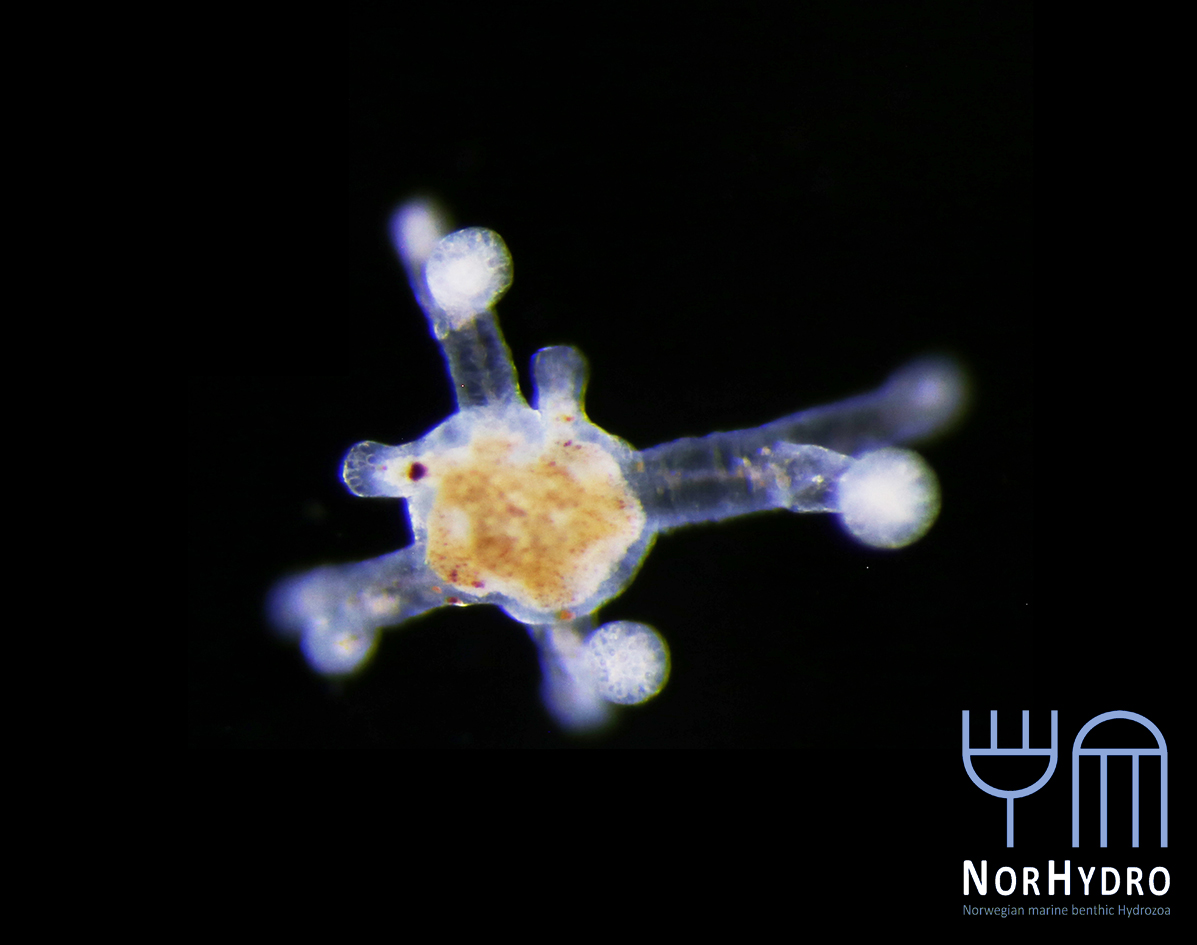

- Eleutheria dichotoma. Photo: L. Martell

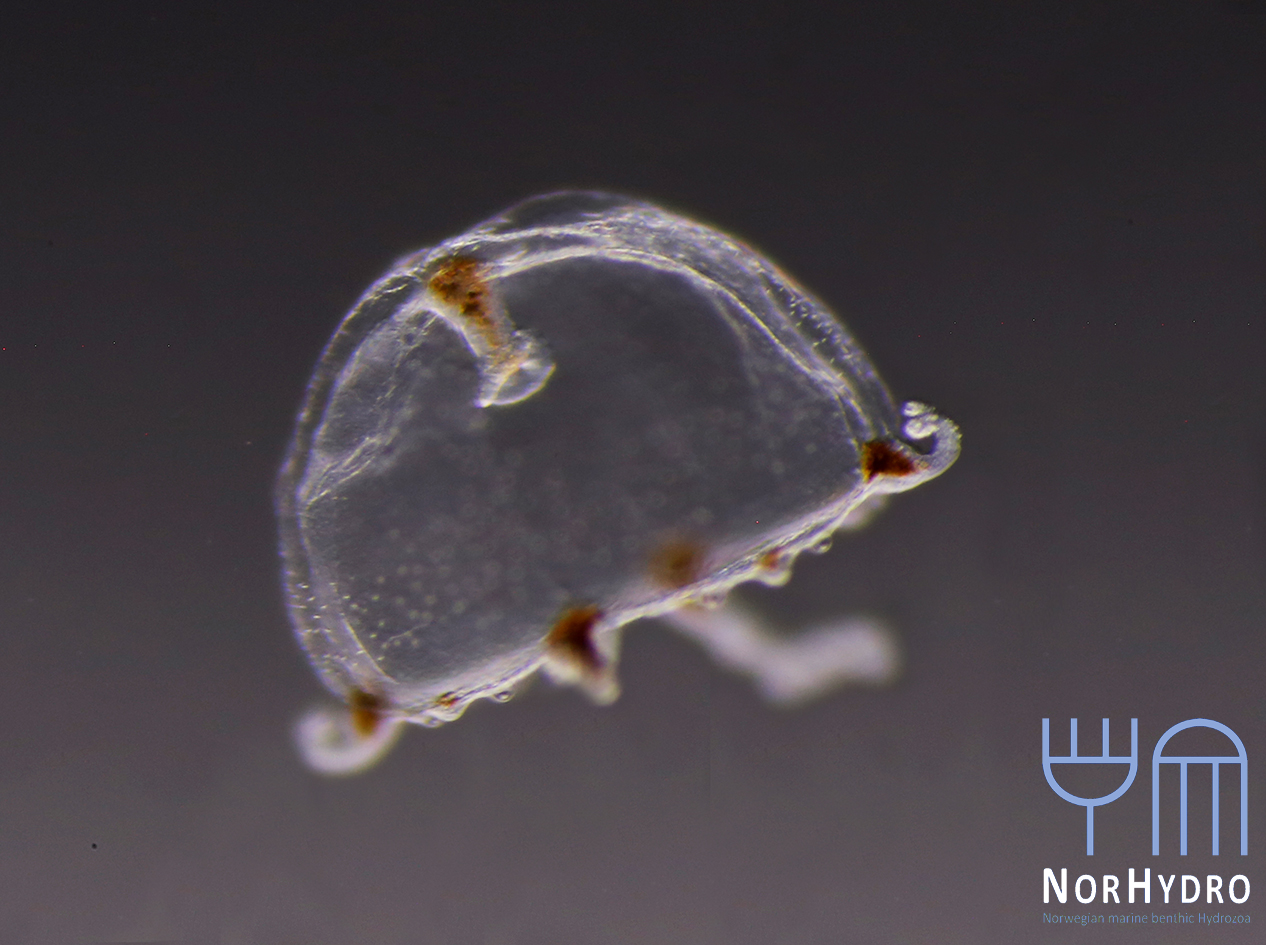

- Clytia sp. Photo: L. Martell

Plan B when the animals (in this case Leuckartiara octona) won’t cooperate and be documented with the fancy camera; bring out the cell phones!

It was a busy week, but combining several projects, bringing together material spanning all of Norway, and working together like this made it extremely productive!

Thank you very much to all the participants, and to all the people who have helped us gather material so far!

-Katrine & Luis

Sea slugs from Vestfold

Larvik & Sandefjord 22.10.2019 – 27.10.2019

From October 22 to October 27, Sea slugs of Southern Norway crossed the Hardangervidda mountain pass to pay a visit to Larvik Dykkeklubb (LDK) and Sandefjord Dykkeklubb (SDK). Vestfold, in particularly the Larvik area, was a thorn in the side for the sea slug project. With fieldwork and collection trips covering most of the Hordaland area (Bergen, Espegrend), Rogaland (Egersund), Mandal (Vest-Augder), Drøbak (Oslofjord area) a lot was left to be discovered still for Aust-Agder and Vestfold. Therefore, a visit to Vestfold was very high on our bucket list.

With Winter just around the corner, we decided to squeeze in a short fieldwork trip to Larvik just before the end of 2019. Me and Anders Schouw drived from Bergen to Larvik with our rented caddy to meet up with Tine Kinn Kvamme and members of the LDK. On Tuesday morning, after packing our mobile laboratory in the car, we drove off to Larvik. In the early evening we arrived at the LDK, there we were welcomed by Lene Borgersen from LDK, who facilitated access to the clubhouse for sorting sea slugs during our stay. That evening was also a club members evening, and I took that opportunity to give a presentation about sea slugs and the Sea slugs of Southern Norway project

- Sea slug presentation for the Larvik Dykkeklubb members. Photo credits Lene Borgersen

- Sea slug presentation for the Larvik Dykkeklubb members. Photo credits Tine Kinn Kvamme

It was a great evening talking about sea slugs with interested club members while eating pizza! The next day Tine, Anders and I met up with LDK member Mikkel Melsom, who joined to help on our hunting for sea slugs

Picture 2. Some sea slugs from Larvik; from left to right; Limacia clavigera, Edmundsella pedata, Diaphorodoris luteocincta, Tritonia hombergii, Tritonia lineata and Cadlina laevis. Photo credits Anders Schouw

Later that day we met up at the SDK clubhouse with Stein Johan Fongen, where I had the opportunity to once again talk about sea slugs this time to the SDK members. This was a very special evening because among the audience, besides SDK members, we also had students from Sandefjord videregående skole (Sandefjord High School)

Sea slug presentation for students of the Sandefjord videregående skole and Sandefjord Dykkeklubb members. Photo credits Tine Kinn Kvamme

In the following days several members of the SDK also joint us collecting sea slugs. Despite the fact that October is known for being not an ideal season to find sea slugs (most species are observed during Winter and (early) Spring) we still somehow ended up with hours of sorting work at the Larvik clubhouse

Cessa Rauch & Anders Schouw sorting sea slugs in the Larvik clubhouse. Photo credits Tine Kinn Kvamme

Overall, we collected 21 different species, all newly registered specimens for the project with regard to this part of the country. It would be great to see what the species abundance would be during a sea slug season like February or March!

Besides sea slugs and enthusiastic club members, another highlight of the week was a visiting seal at SDK! On our last day of fieldwork, a young seal was very bold and decided to rest close to the clubhouse in the harbor. It let people come up really close, which was great for making cute seal pictures. Cherry on the cake, in my opinion!

On Sunday the tree of us had to say goodbye, Tine would go back to her hometown Oslo and Anders and I would cross the snowy mountains again back to Bergen. It was a short but sweet visit and great opportunity to meet members of Larvik and Sandefjord dykkerklubbs. I therefore want to thank LDK and SDK for their interest, enthusiasm and help for the few days Anders, Tine and I were around. I surely hope we will meet again next year, and find many more sea slugs. And of course, thanks to Anders and Tine for helping again, hope we can share many more sea slug adventures together

Left to right; Tine Kinn Kvamme, Cessa Rauch and Anders Schouw in front of the Larvik Dykkeklubb were most of the ‘lab’ work was done. Photo credits Lene Borgersen

More sea slugs:

Do you want to see more beautiful pictures of sea slugs of Norway? Check out the Sea slugs of Southern Norway Instagram account; and don’t forget to follow us. Become a member of the Sea Slugs of Southern Norway Facebook group, stay updated and join the discussion! Hunger for more sea slug adventures, check our latest blog posts.

Explore the world, read the invertebrate blogs!

– Cessa

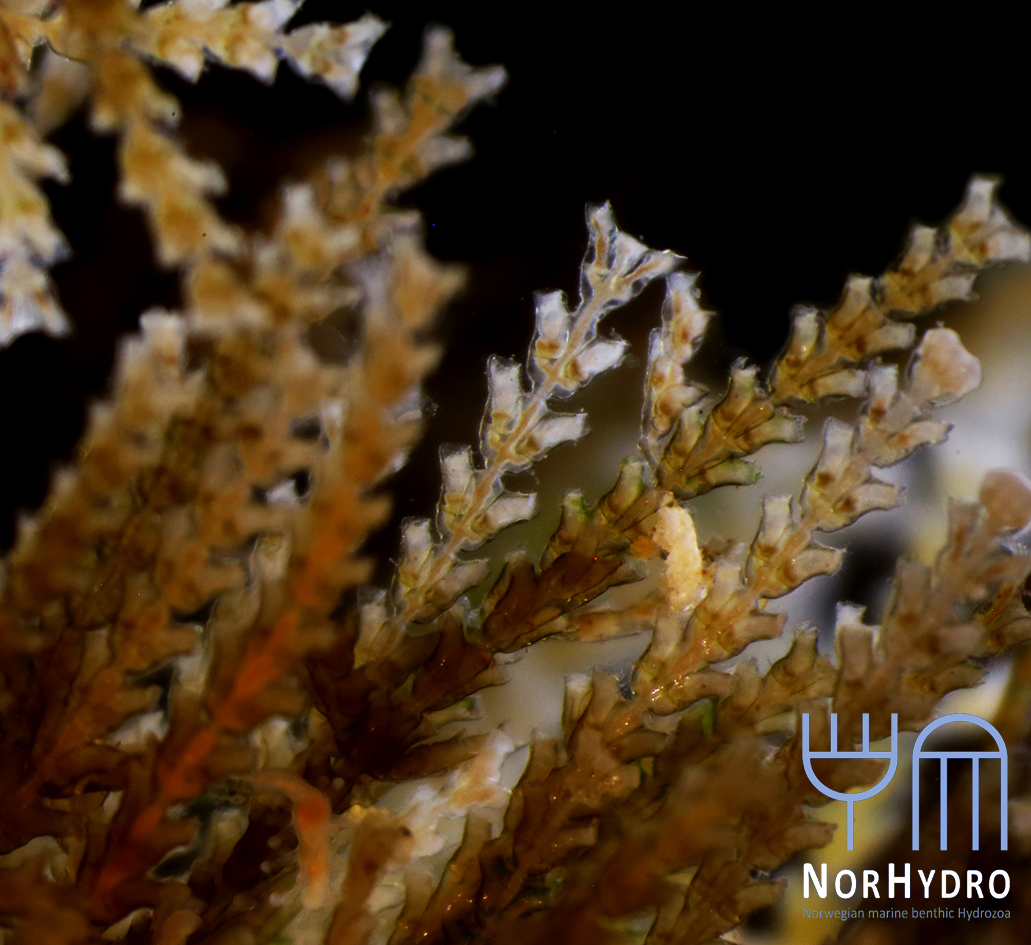

Invertebrates in harbours

Harbours and marinas are interesting places to look for marine creatures. These environments are usually teeming with life, but a closer look often reveals that their communities are strikingly different from the ones living in adjacent natural areas. Piers and pontoons offer new surfaces for many algae and animals to grow, and the maritime traffic of large and small boats allow for an intense movement of organisms, making harbours some of the preferred spots for newcomers (what we called introduced species) to settle. Many surprises can be expected when sampling for invertebrates in these man-made habitats, which is why our artsprosjekt NorHydro teamed up with project PolyPorts (based at the NTNU University Museum) to explore the hidden diversity of worms and hydroids in the Norwegian harbours.

Last year, PolyPorts sampled extensively in some of the main Norwegian harbours (including Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, and Stavanger); but for this year’s sampling season our two projects headed first south (to the harbours and marinas of Sørlandet), and then west (to Bergen).

In the south, we sampled several ports and marinas from Kristiansand to Brevik (including Lillesand, Grimstad, Tvedestrand, and Risør, thus covering a large portion of southern Norway). In Vestlandet we concentrated our efforts in the area of the port of Bergen, Puddefjorden and Laksevåg, as well as Dolvika.

- The sampling team in Sørlandet included Torkild Bakken and Marte Svorkmo Espelien (NTNU University Museum), Eivind Oug (NIVA) and me (UMB and NorHydro)

- We sampled small marinas…

- and larger harbours and port areas.

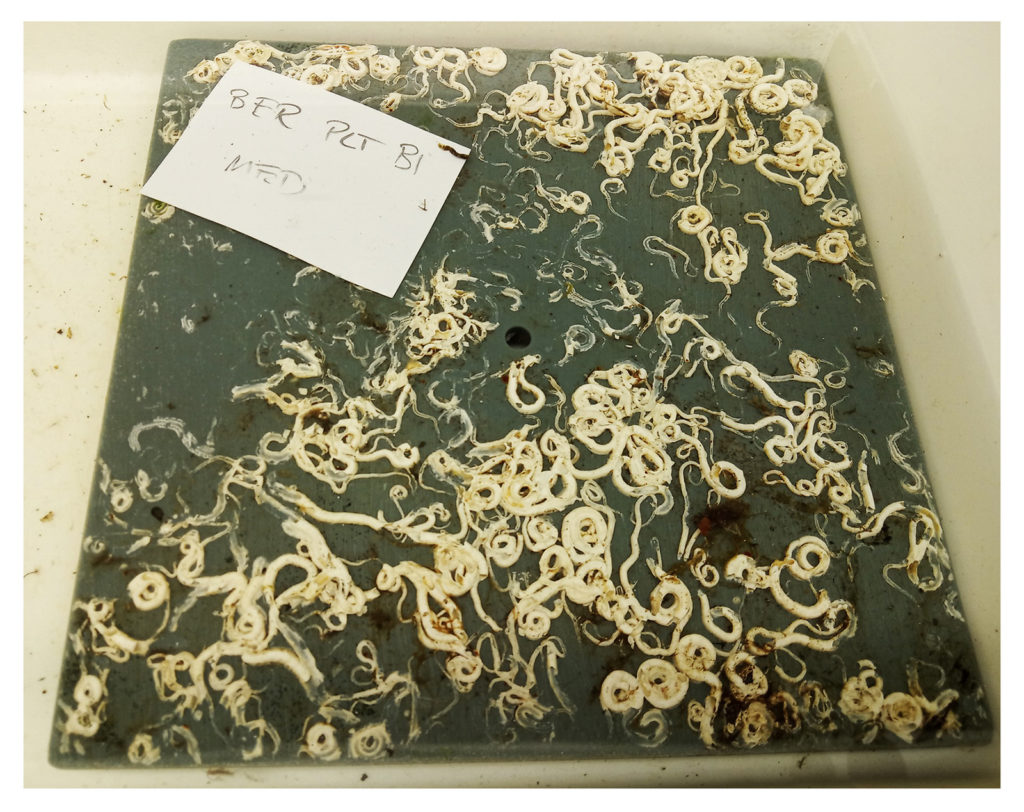

- Last year we put a series of panels in 9 sites in the port of Bergen to see what would grow on them. Looks like this one was particularly attractive for polychaetes. Photo: Maria Capa

- The research vessel Hans Brattström took us sampling in small marinas in Hordaland. Photo: Maria Capa

Although it could be surprising that heavily trafficked (and sometimes quite polluted) harbours support a high diversity of invertebrates, this was actually the case for every single port we surveyed.

- The most surprising result for NorHydro during our trip was finding Cordylophora caspia in almost all the localities we visited.

- Ectopleura larynx was one of the most common – and conspicuous – hydroids in marinas and harbours.

- Many jellyfish belonging to genera Aurelia and Cyanea were present during the sampling.

- The hydroids were home to many other organisms, including the introduced skeleton shrimp Caprella mutica

- In Sørlandet we found many reproductive colonies, like this Gonothyraea lovenii, but at the same time those species had already stopped reproducing in the colder waters of Bergen.

- The ascidian Styella clava was another of the introduced species we constantly found.

All our sampling areas had pontoon pilings and mooring chains covered in colourful seaweeds and animals, and reefs of native and introduced mussels and oysters that provided a home for sea squirts, skeleton shrimps, bryozoans and hydroids. For NorHydro, perhaps the most surprising result came from the brackish areas that we analyzed, where large populations of Cordylophora caspia were found. This species is not native to Norway and had not been observed in so many Norwegian localities before, making for an interesting finding to explore even further through the analysis of DNA.

– Luis

Keep up with the activities of NorHydro here in the blog, on the project’s facebook page and in Twitter with the hashtag #NorHydro.

World Congress of Malacology 2019: 10 – 17 August 2019

On August 10, four delegates from the University Museum of Bergen made their way to Monterey Bay California, USA.

Attending the World congress of Malacology 2019, from left to right; Jenny Neuhaus, Justine Siegwald, Manuel Malaquias & Cessa Rauch

This year the World Congress of Malacology took place at the Asilomar conference grounds in Pacific Grove, Monterey. Monterey Bay is well known among many marine biologists due to its world-famous aquarium and aquarium research institute (MBARE), many marine protected areas (7; including the Asilomar State Marine reserve, close to where the conference was held), Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University, Steinbeck Center (although located in Salinas, close enough to make it count). The latter was named after the famous marine biologists John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts from the Monterey County; Among other works they contributed to marine biology with their famous books ‘The sea of Cortez’ and ‘Between Pacific Tides’. All in all, Monterey Bay seems like an exciting place to be for us marine biologists.

The World Congress of Malacology was organized and chaired by the famous Terry Gosliner (Terry described more than 1000 species of sea slugs!) a senior curator of the California Academy of Sciences. About 300 participants contributed to a very lively and busy scheduled week

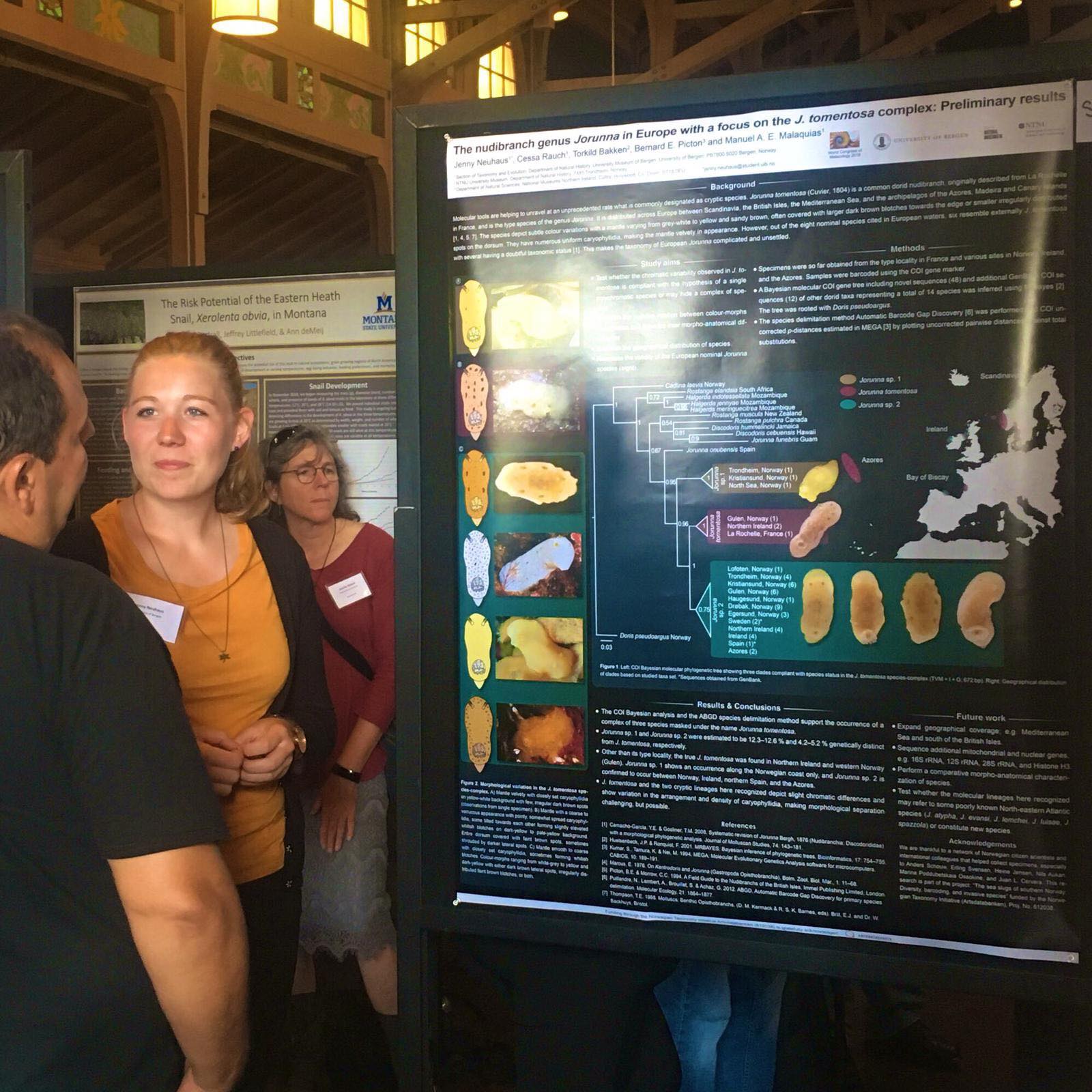

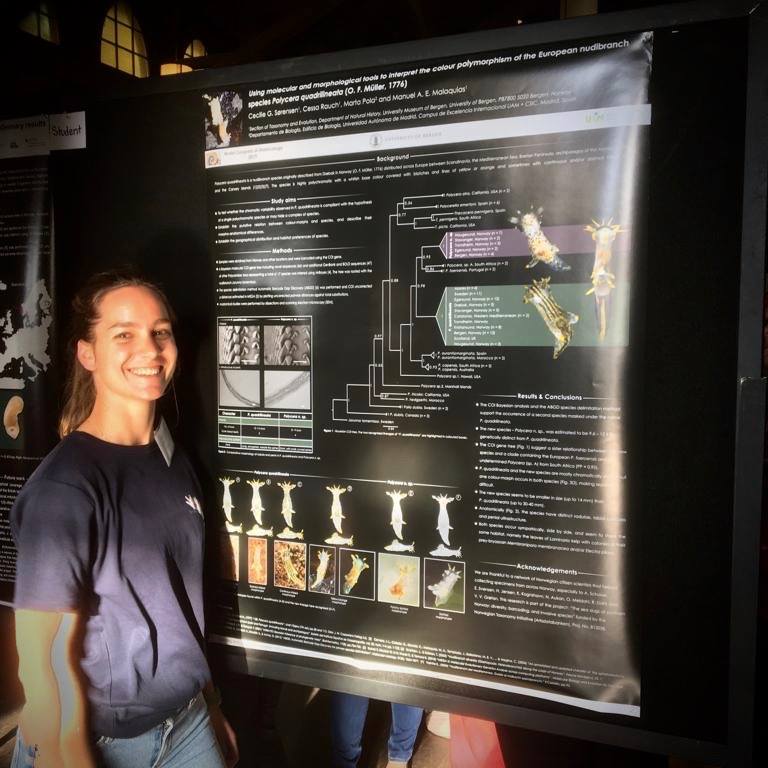

Registration for the conference started on Sunday the 11th of August, but Monday was the real kick off of the program with fabulous keynote speakers such as Geerat Vermeij, David Lindberg, Susan Kidwell, etc.. During the poster session Jenny Neuhaus and Cecilie Sørensen, two of our master students working in close collaboration with the Museum project Sea Slugs of Southern Norway have presented their preliminary results. Unfortunately, Cecilie could not join us due to time constraints, and the poster was presented by Cessa

- Jenny presenting her work on Jorunna tomentosa

- Cessa presenting Cecilies work on Polycera quadrilineata

On Tuesday we had a crammed agenda with multiple speakers talking at the same time, divided over the different halls in a variety of sessions. It was a busy day of running around trying to catch those talks one were most interested in. Justine had her talk in the Systematics session about her PhD research on Scaphander titled; First global phylogeny of the deep-sea gastropod genus Scaphander reveals higher diversity, a possible need for generic revision and polyphyly across oceans. It received a lot of attention and numerous questions afterwards, it was great to see how her research was perceived with so much curiosity and enthusiasm.

Wednesday we had a day off filled with several excursions. Jenny went to the whale watching trip, Justine went to spot marine mammals and Cessa to a trip along the coast to meet and greet the Californian red giants. The trips were all well organized and a very nice break off the week as the many presentations and sessions made the days long and intense. The whale watching trip took place in Monterey Bay and Jenny was lucky enough to observe the mighty blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus, plenty of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), and several sunfish (Mola mola) swimming at the surface. It was an incredible experience for her to be able to watch the animals thrive in the great Pacific Ocean.

The trip to South Monterey was along the California’s rugged coastline and provided one of the most spectacular maritime vistas in the world. It has peaks dotted with the coast redwoods that go all the way to the water’s edge. The trip took you to Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park where we got the opportunity to walk through the redwood forest. Along the way we stopped at numerous scenic vistas, it was definitely a memorable day .

On Thursday, all well rested, we had another hectic day full of presentations, this time it was Cessa’s turn, she would talk about the ‘Sea slugs of Southern Norway project as an example of citizen science’ (Picture 8. Cessa presenting the sea slugs of Southern Norway project). It was placed in the citizen science session and many that attended had questions about citizen science which constituted a great opportunity to share our experience acquired during the last year of our project.

Friday, on the last day of the conference, Manuel had his talk about the phylogeny and diversity of the Indo-West Pacific gastropods Haloa sensu lato (Cephalaspidea: Haminoeidae): Tethyan vicariance, generic diversity, and ecological specialization. This was part of the recent collaborative work his previous PhD student Trond Oskars

The day was closed off with a big dinner and the award ceremony. Prizes were handed out to the best student’s oral and poster presentations. Jenny was awarded by the Malacological Society of London the prize for the best student poster. This was a very exciting way to end a successful conference trip!

-Cessa & Jenny

Many hands (plus some tentacles and legs) make light work

In the last months, our project NorHydro has been very busy with sampling trips and outreach; we have been collecting hydroids in Southern Norway, presenting our results in festivals, and hunting for hydrozoans inside mythical monsters as well as around Bergen, the project’s hometown. All of these activities sound like a lot of work, and they certainly take a fair amount of time and effort, but the good thing is that NorHydro has never been alone in its quest for knowledge of the marine creatures: on the contrary, this has been the season of collaborations and synergies for our project!

At the end of August, for example, we attended the marine-themed festival Passion for Ocean; where we shared the stand of the University Museum of Bergen with a bunch of colleagues, all working on several kinds of marine creatures, from deep sea worms and sharks to sea slugs and moss-animals. It was a great opportunity to talk to people outside academia (including children!) about our work at the museum, and also to show living animals to an audience that does not venture too often into the sea.

Our stand at the Passion for Ocean festival was incredibly popular with the public – we feel like most of the 5-6000 people who attended P4O must have dropped by to talk to us! Photos: K. Kongshavn and M. Hosøy

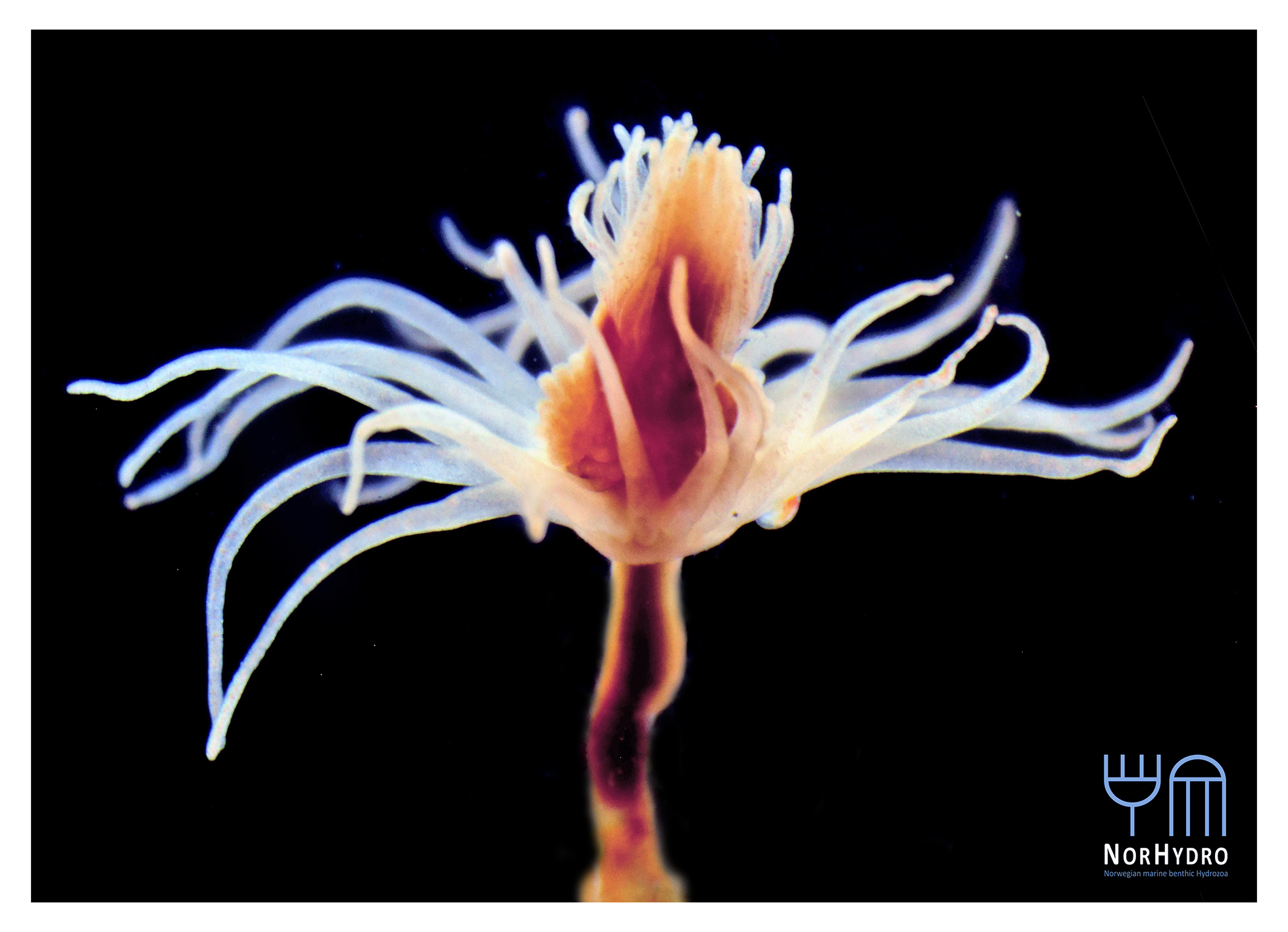

Although most of the people in Bergen are familiar with jellyfish, very few of them would know that most jellies are produced by flower-looking animals living in the bottom of the ocean, so the participation of NorHydro was met with a lot of surprise and curiosity. The festival was a big success (you can read a more about the experience in the Norwegian version of the blog), and hopefully we will get the chance to join again next year.

Later on, in September, we set off for a field trip to the northerly area of Saltstraumen, in the vicinity of the Arctic city of Bodø. For this trip NorHydro was again in collaboration with the UMB-based project “Hardbunnfauna” (Jon and Katrine represented the hard-bottom dwelling invertebrate fauna scientists) and also with Torkild Bakken (from NTNU University Museum, with his project “#Sneglebuss”). For me, Saltstraumen was definitely an exciting place to go; the strong currents of Saltstraumen have been the cause of death of too many sailors and seamen in the past, so in the collective mind the area has become some sort of man-eating whirlpool similar to the Mediterranean Charybdis… I don’t get to sample inside a mythological creature very often! Underneath the water though, Saltstraumen is teeming with life.

During this trip, we were prepared to sample in the littoral zone (and we did), but more importantly we were lucky enough to meet several enthusiast citizen and professional scientists that were diving in the area and shared with us some of their observations.

We were treated to extremely nice underwater pictures of invertebrates by Bernard Picton and Erling Svensen, and all the participants in the activities of the local diving club (Saltstraumen Dykkecamp) were very keen in providing us with suggestions, animals, images and impressions that made our sampling trip a total success.

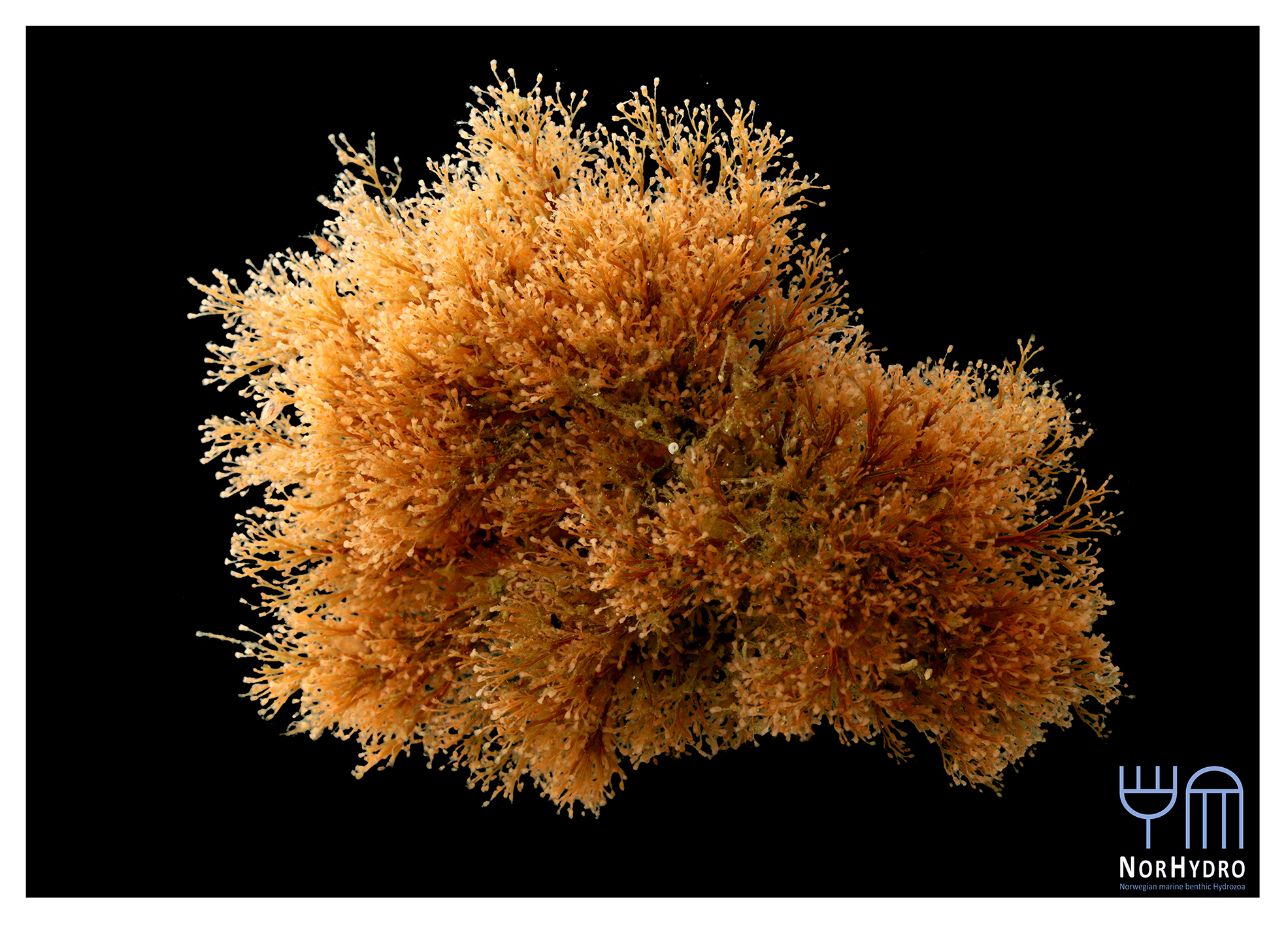

The area was dubbed as a “hydroid paradise” (likely due to the strong currents that favor the development of large hydrozoan colonies), and many new records and even perhaps new species are present in the region.

- A colony of Hydractinia growing on the shell of a hermit crab

- Large hydroids like Tubularia indivisa provide refuge and food for many other species of invertebrates

- A medusa of Bougainvillia about to be released from the hydroid colony

- Small corynid hydroids were often growing on other invertebrates and algae

- Polyps of Clava multicornis

- Large colonies of hydroids (like this Eudendrium) were common in the area.

For those of you that know Norwegian, you can read another interesting account of our trip here, and there is even a small service covering our adventures filmed by the regional TV channel NRK Nordland here.

For those of you that know Norwegian, you can read another interesting account of our trip here, and there is even a small service covering our adventures filmed by the regional TV channel NRK Nordland here.

The TV service is worth a look to see the beautiful underwater images of the Norwegian coast even if you’re not familiar with the language!

– Luis

Success in the South; fieldwork in Mandal

From May 20th to 27th the sea slugs of Southern Norway team headed South to Mandal to pay a visit to the Mandal dykkerklubb and try to find more enthusiastic citizen scientist to join the sea slug project. We had a few special guests invited for the week and the team consisted of Cessa Rauch, Manuel Malaquias, Anders Schouw, Erling Svensen, Nils Aukan, Tine Kvamme and Heine Jensen. In Mandal the head of the club Erling Tønnessen would be there to help us around and organize club activities for collecting the sea slugs.

The first day basically consisted of traveling to Mandal and setting up our “hyttes” for a week of sea slug hunting. As usual we underestimated the amount of space needed to bring our ‘mobile’ lab to the camping site in Mandal. Even though a station wagon theoretically fit a family of five plus luggage, it was barely enough space for a family of sea slug hunters with their equipment.

We ended up with a challenging Tetris game and me being squeezed between microscopes and jars in the back seat, still, no complaints! At least I was spared for driving the long hours from Bergen all the way to Mandal, that every local would be able to fix in less than 7 hours, we managed to take 12. I guess the car was heavy loaded! Manuel did a fantastic job while Anders and me where dozing off. Eventually we managed to arrive safely in Mandal and there we were greeted by our team of citizen scientists that helped us out through the week. They as well had to travel from all corners of the country; Kristiansund, Egersund, Oslo and Sarpsborg. It was quite special to arrive all together in Mandal with only one thing in our minds; finding sea slugs!

The next days in collaboration with the local Mandal dykkerklub and their fantastic club boat equipped with a lift to get people in and out of the water, we operated most of the sampling activities. After a day out collecting we would all go back to our cabins and start photographing and registering the samples.

- After a long day in the field, sorting and documenting the sea slugs would be done in the hytte, with Tine (middle), picture Erling Svensen

- With (left to right) Heine, Nils and Anders, picture Erling Svensen

Even though late spring is supposedly not the best season for collecting sea slugs, due to low abundance of the different species, together we were still able to collect 47 different species!

On our last day of the expedition, the Mandal dykkerklubb organized an evening social gathering for their members in which we had the chance to give a presentation about sea slugs and the project, and to give away a few sea slug sampling kits to all those interested.

Picture 5. Cessa and Manuel presenting the sea slugs of Southern Norway project, picture Erling Svensen

Picture 6. Interested dive members of the Mandal dykkerklubb showing up to learn more about sea slugs and having a good time, picture Erling Svensen

With every fieldwork trip we get more experienced in the organization and execution of the event and this is definitely paying off in the diversity of species we manage to collect. We were not able to register so many species before as with this fieldwork trip to Mandal. This was by far the most successful expedition and together with the joined efforts off all the excellent citizen scientist we formed a real professional sea slug team!

Picture 7. Group picture of the expedition members on board of the Mandal dykkerklubb boat, left to right; Heine Jensen, Erling Svensen, Anders Schouw, Cessa Rauch, Tine kinn kvamme, Nils Aukan and the expedition leader Manuel Malaquias in front, picture Erling Svensen

At the moment we are waiting for the first DNA barcode results in order to confirm the species diversity we found that week. An update will follow; but Manuel and I would like to take this opportunity to gratefully acknowledge all the efforts and interest of our team members of that week and the good times we had together! Hope to meet you all again soon during yet another sea slug hunt! Tusen takk!

-Cessa

Royal hydrozoans and noble snails at Her Majesty the Queen of the fjords

As part of our continuous quest for hydrozoans and snails, we (Luis and Justine) recently embarked on a trip to the mighty Hardangerfjord on board the RV Hans Brattström. This is an area that we at the museum are keen to explore, since there have not been many sampling efforts in Hardanger in recent years, at least not after the joint survey carried out in the years 1955–1963 and in which Hans Brattström himself (the scientist, not the ship) took part. The Hardangerfjord has changed a lot since the 1960s, developing into one of the major fish-farming regions of Norway while at the same time retaining its touristic and agricultural vocation, so it is very interesting to come back and see if and how the invertebrate communities have also changed.

…but it quickly turned into a more ‘typical’ western Norwegian weather. Fortunately we were prepared for the rain!

The Queen of the fjords, as Hardangerfjord is sometimes known, is the second longest fjord in Norway and the fourth longest in the world, which means that we had quite a lot of ground to cover in our two day-trip if we wanted to have at least a brief look at the diversity of habitats and animals living in its waters. For this trip, we settled for a sampling scheme involving 9 stations distributed in the middle and outer parts of Hardanger, and we decided to leave the innermost part of the fjord for a future occasion. We looked at the animals living in the bottom of the fjord (benthos), the water column (plankton) and also deployed a couple of traps in order to catch specific critters. We explored rocky sites, sandy bottoms, muddy plains and kelp beds, and found an interesting array of animals in all our samples.

Some of the animals we saw (most of them were actually returned to the sea):

- Aphrodita aculeata

- Porania pulvillus

- Tubulanus annulatus

- The hermit crab Pagurus prideaux with the cloack anemone Adamsia palliata

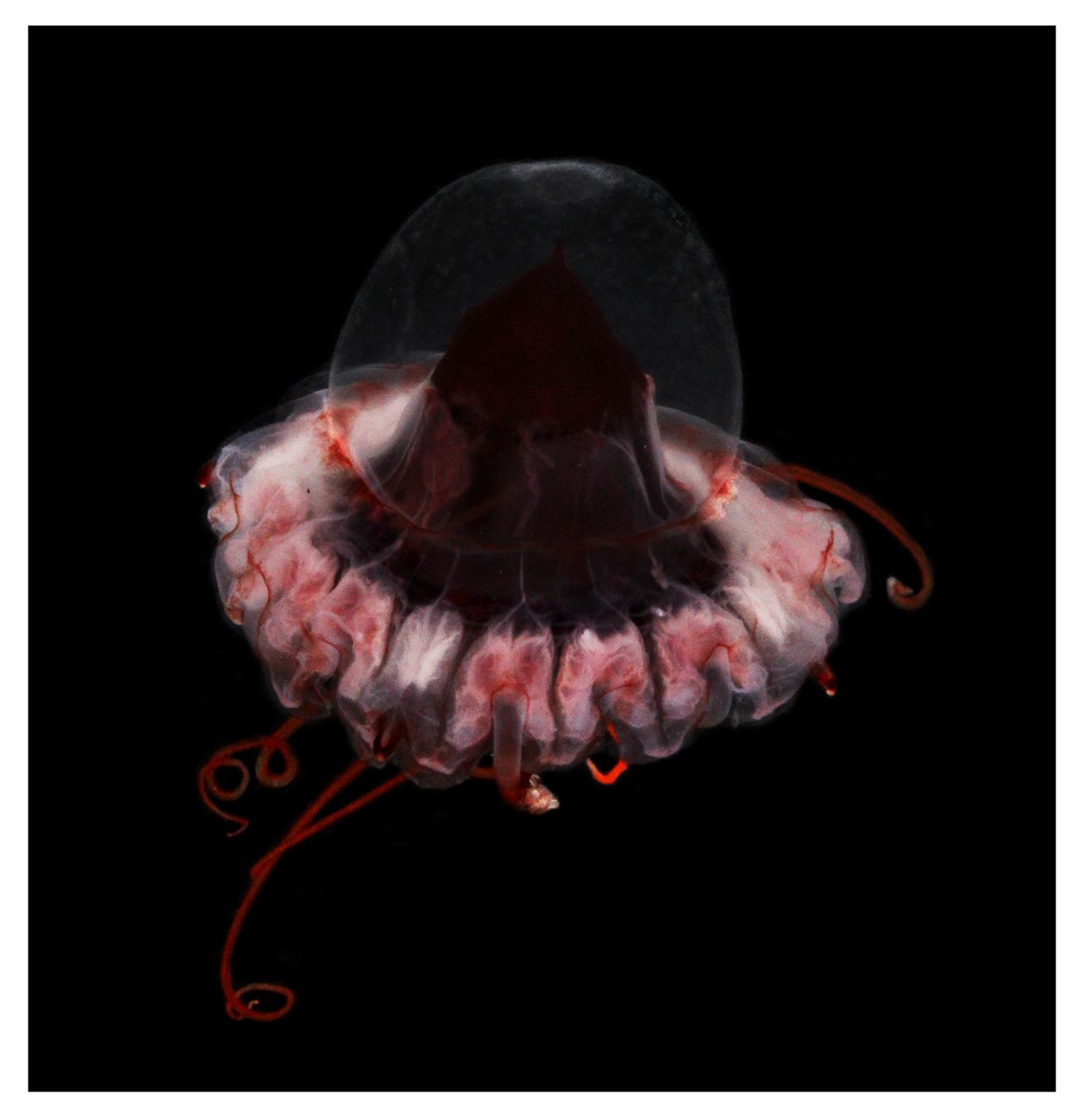

- Periphylla periphylla

- Ceramaster granularis

- Polycera quadrilineata

Without any doubt, the highlights of our trip were the snail Scaphander lignarius and the hydrozoans Eudendrium sp. and Laodicea sp. The colonies of Eudendrium sp. were relatively abundant in shell- and rock-dominated bottoms, but their small size and not reproductive status prevented us from identifying them to species level right away. For a correct identification, we now have to look closely at the stinging cells (nematocysts) of the hydroids, and of course we will also try to get the DNA barcode of some of the specimens. Unlike Eudendrium sp., which lives in the bottom of the sea, our specimens of Laodicea sp. were swimming around in the water column. This species is interesting because previous DNA analysis have shown that, although they look like each other, different species of Laodicea coexist in Norwegian waters, so we are looking forward to obtain the DNA barcode of the jellies from Hardanger to compare it with the sequences we have from other parts of Norway.

Scaphander lignarius was quite the surprise finding. We really wanted to collect some individuals, but our hopes were not very high and we were mostly convinced that we would not see any during our trip. Luckily for us, there were several of them happily crawling around the mud in two of our stations! S. lignarius is one of the few representatives of the Scaphandridae family in Norway. This family of bubble snails is of particular interest to us to study the biogeography and speciation process of invertebrates in the deep sea on a worldwide scale, since members of the family are distributed all around the world, and most tend to inhabit depths below 500m. Sampling some of them will definitely help that project!

All around, this was a quite successful sampling trip, with many specimens collected to be added to the Museum Collections, and which will be very useful to many different research projects!

– Justine and Luis

PS: You can find more updates on our Artsdatabanken project NorHydro here in the blog, on the project’s facebook page and in Twitter with the hashtag #NorHydro.

References and related literature about the survey of the Hardangerfjors in 1955–1963

Braarud T (1961) The natural history of the Hardangerfjord, Sarsia, 1:1, 3-6.

Brattegard T (1966) The natural history of the Hardangerfjord 7. Horizontal distribution of the fauna of rocky shores, Sarsia, 22:1, 1-54.

Lie U (1967) The natural history of the Hardangerfjord 8. Quantity and composition of the zooplankton, September 1955 – September 1956, Sarsia, 30:1, 49-74.