The 6th International Jellyfish Blooms Symposium was the last big academic event in 2019 attended by team NorHydro, and we were very happy to have presented our project in such a relevant meeting!

Team NorHydro at the 6th Jellyfish Blooms Symposium, from left to right: Maciej Mańko (University of Gdansk – Poland), Aino Hosia (UiB – UMB), Joan J. Soto (UiB – Sars Center), and Luis Martell (UiB – UMB).

In many ways, the Jellyfish Bloom Symposium (JBS) is the most important meeting of scientists working with medusozoans in the world. Professionals from different countries, backgrounds and lines of research meet every 3 years in this symposium to present their results, discuss new findings, and chat with colleagues about the state of knowledge in the group. So of course our Artsdatabanken project NorHydro had to be present, especially after a session focused on polyps was announced for this particular edition. The importance of polyp stages – the object of study of NorHydro – is now widely recognized in jellyfish biology, and understanding the ecology and diversity of polyps has become a key point in the study of jellyfish blooms.

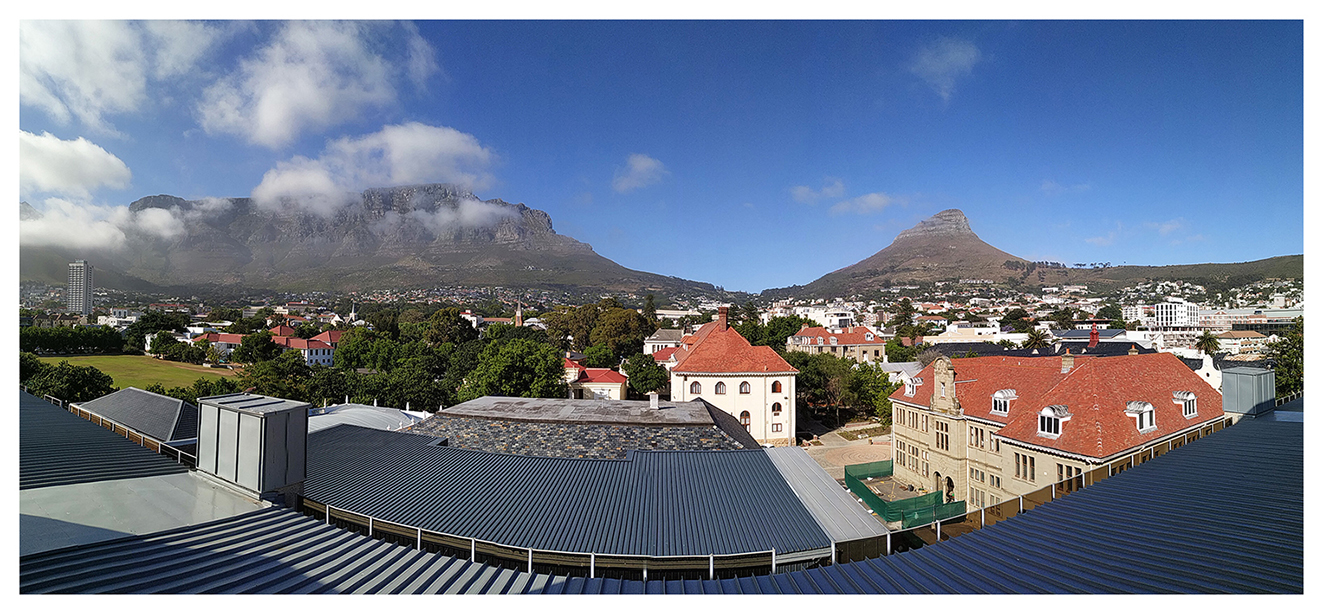

This time, it was the turn of the University of the Western Cape, Iziko South African Museum and the Two Oceans Aquarium to host the JBS, which was held in Africa for the first time.

Iziko Museum was the venue for the oral presentations and poster sessions. The way to the auditorium was marked by jellyfish but we still had to pass under the vigilant eyes of a giraffe.

The city of Cape Town provided a beautiful setting for discussions on gelatinous matters and sharing of jellyfish-related stories, and we even got to see some of the local hydrozoans from the surroundings, both in the aquarium and in the sea.

- We had a fantastic view of Table Mountain from just outside the auditorium…

- and an even more spectacular one from the top of Lion’s Head. Pictures: Joan J. Soto Àngel.

Not everyone was happy with the high concentration of jellyfish researchers in Table Mountain. Photo: Joan J. Soto Àngel

We were lucky to see some hydrozoans by the sea. Several specimens of the siphonophore Physalia physalis (top left) and the anthoathecate Velella velella (top right) were stranded in Diaz Beach, near the Cape of Good Hope (bottom).

The oral presentations and poster sessions covered many subjects on jellyfish biology, not only the dynamics of polyps but also the relationship between jellyfish and humans, the role of jellyfish in the ecosystem, and the diversity of medusa, ctenophores and salps.

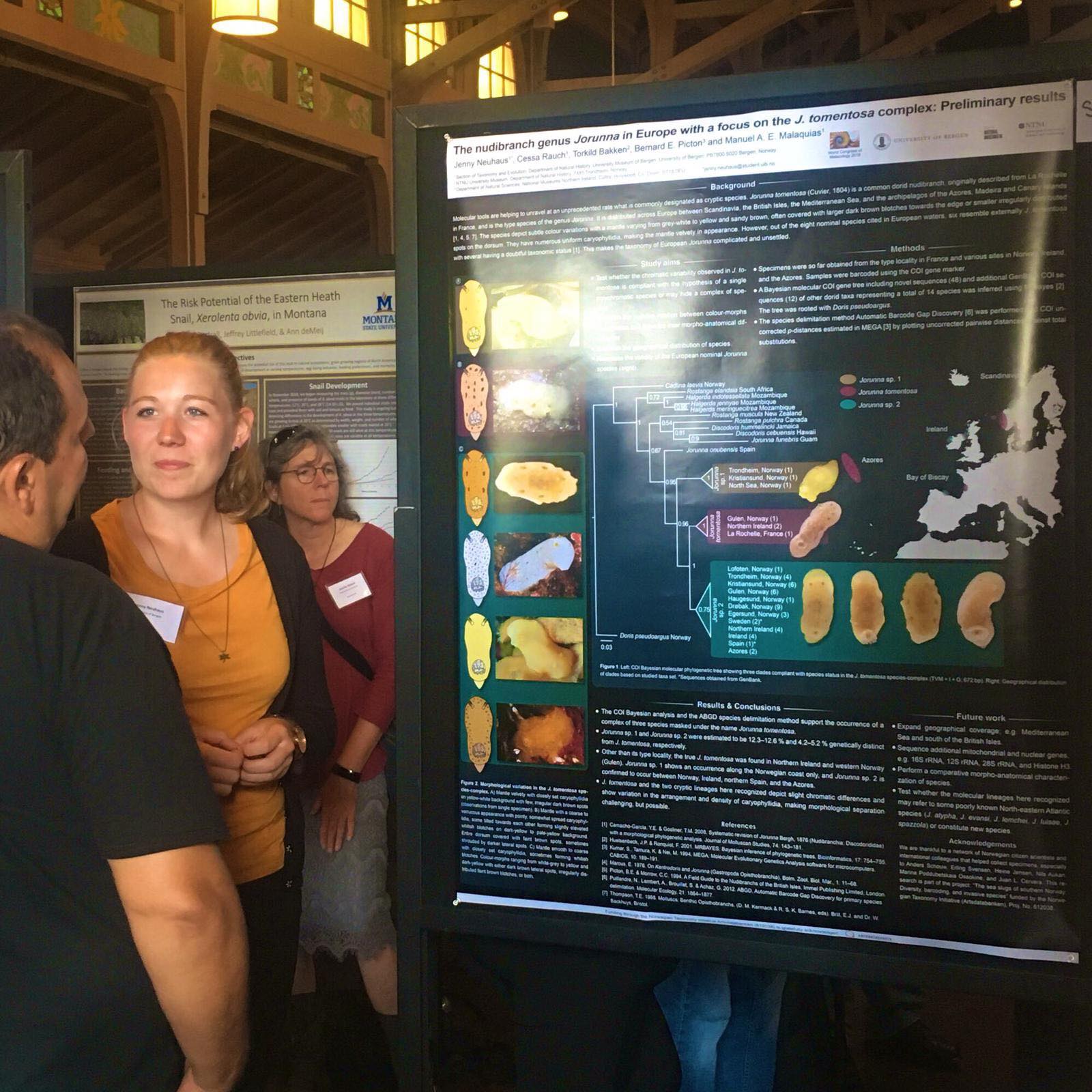

- Snapshots of the presentations given by NorHydro partners and friends.

- The whale hall where the poster sessions took place. NorHydro partner Maciej Mańko won the best poster award for his work on Arctic jellies.

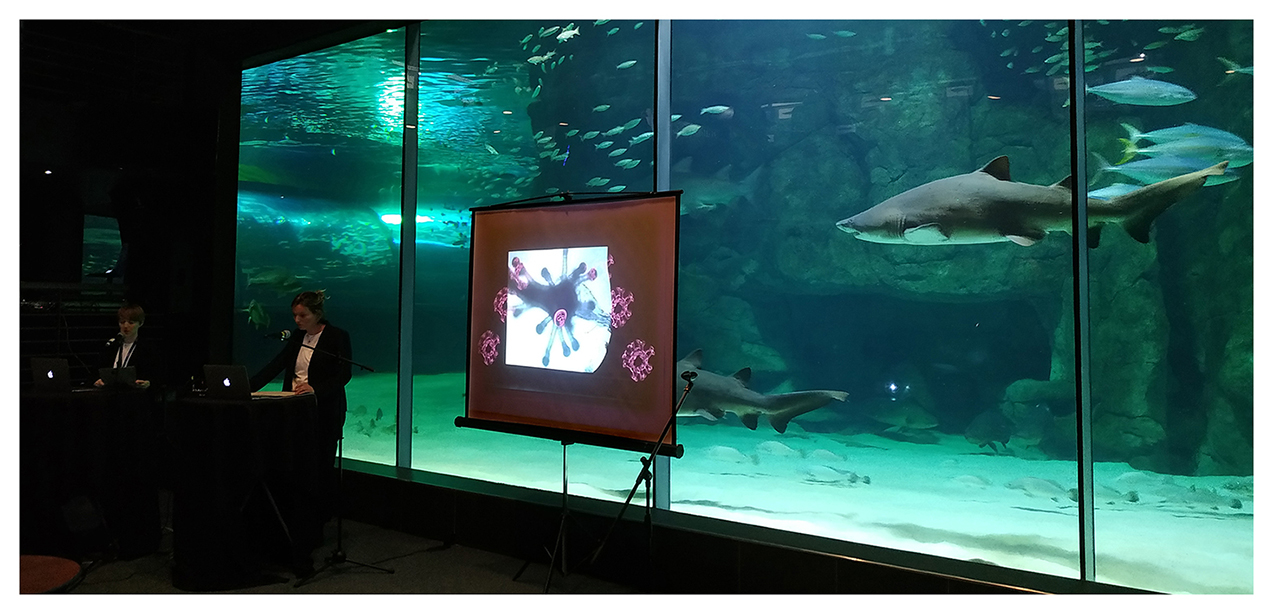

- The symposium started with an artistic performance called “The Institute of Jellyfish”, followed with attention by the sharks of the aquarium.

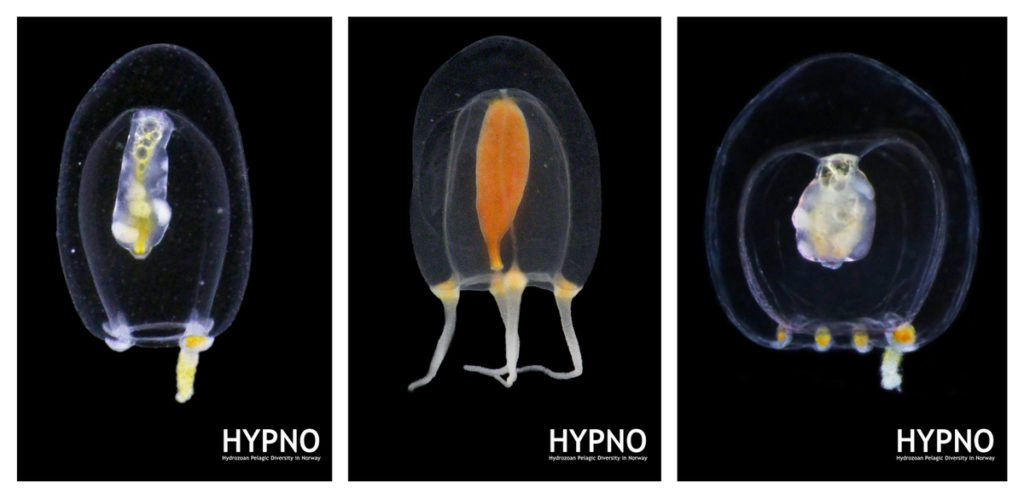

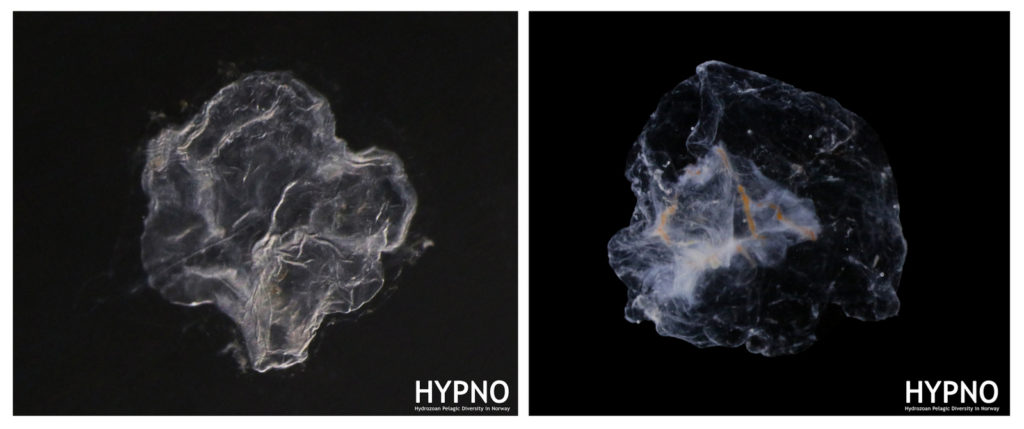

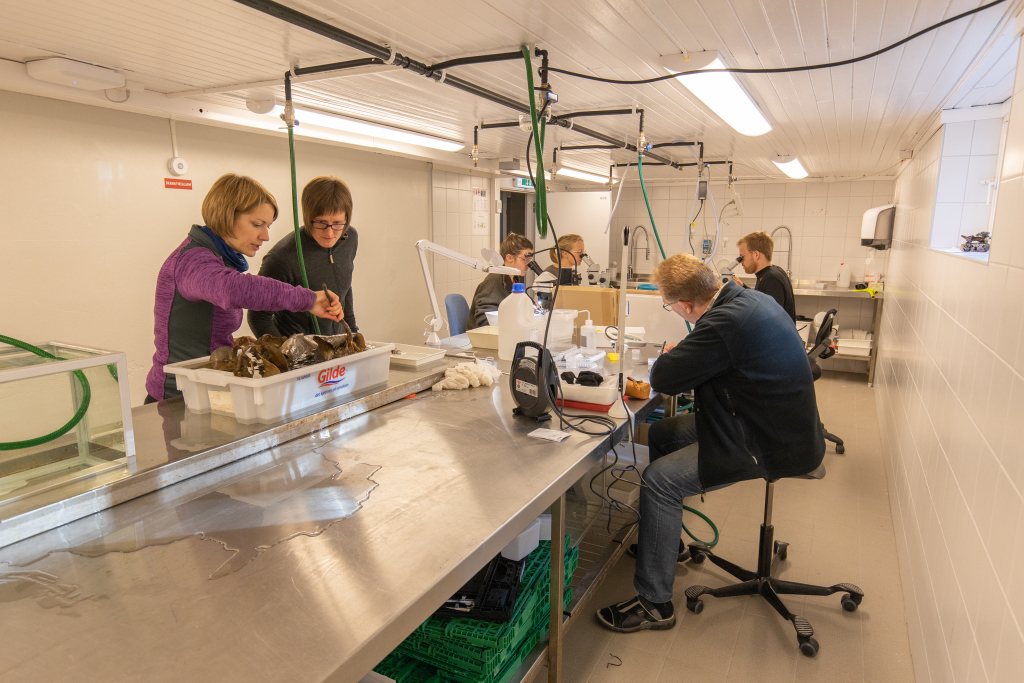

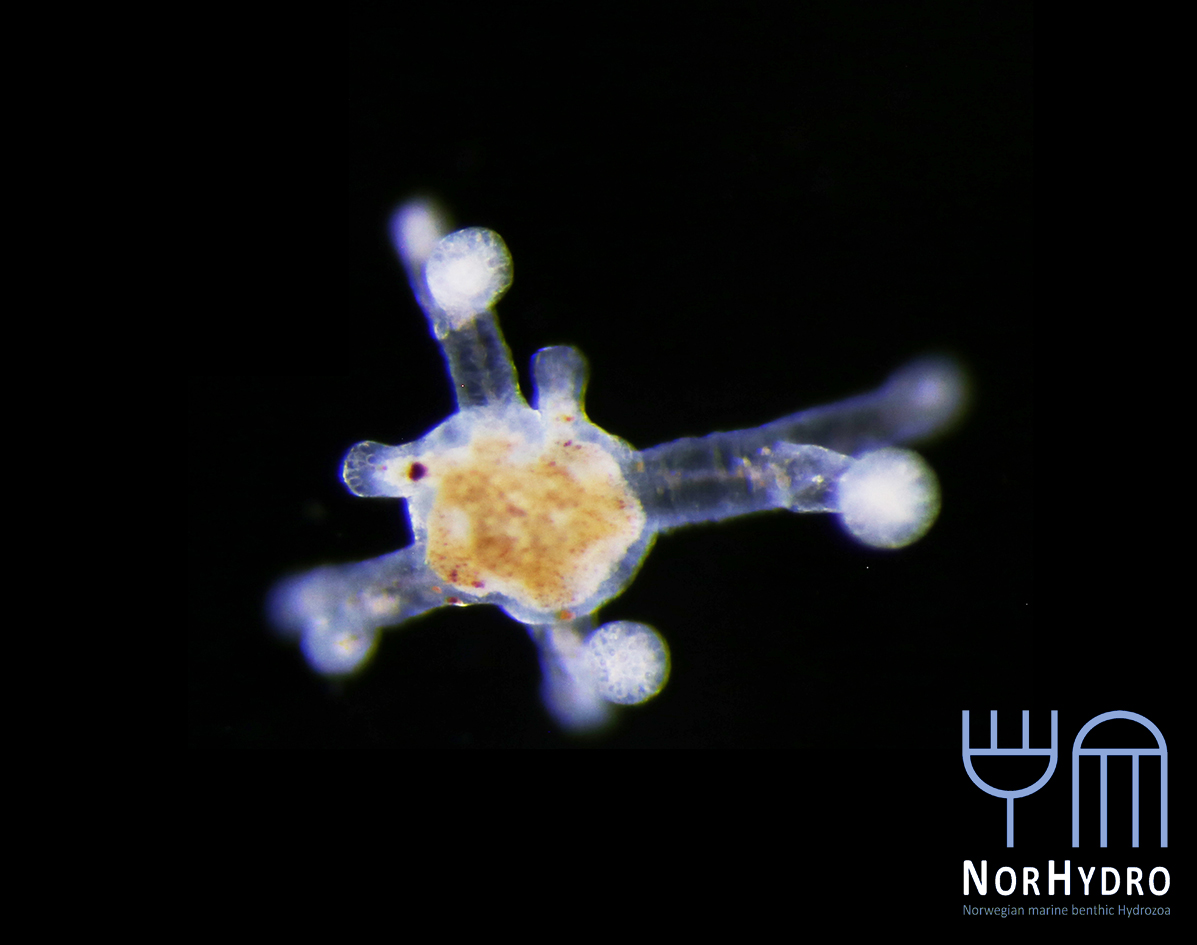

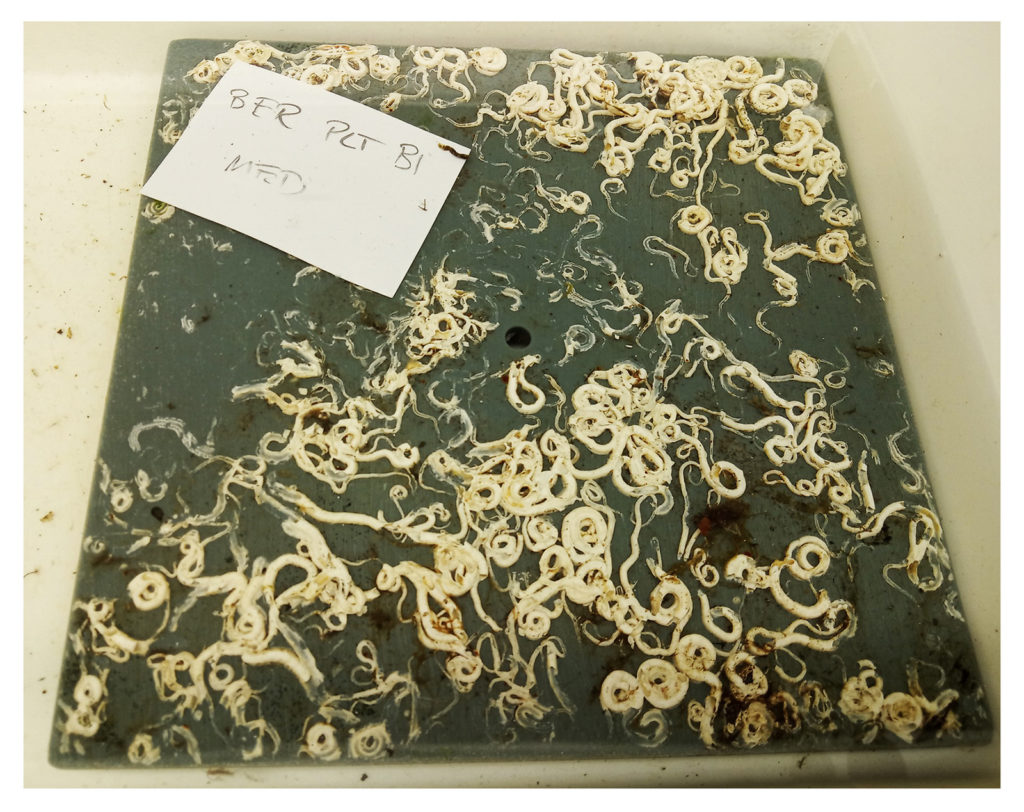

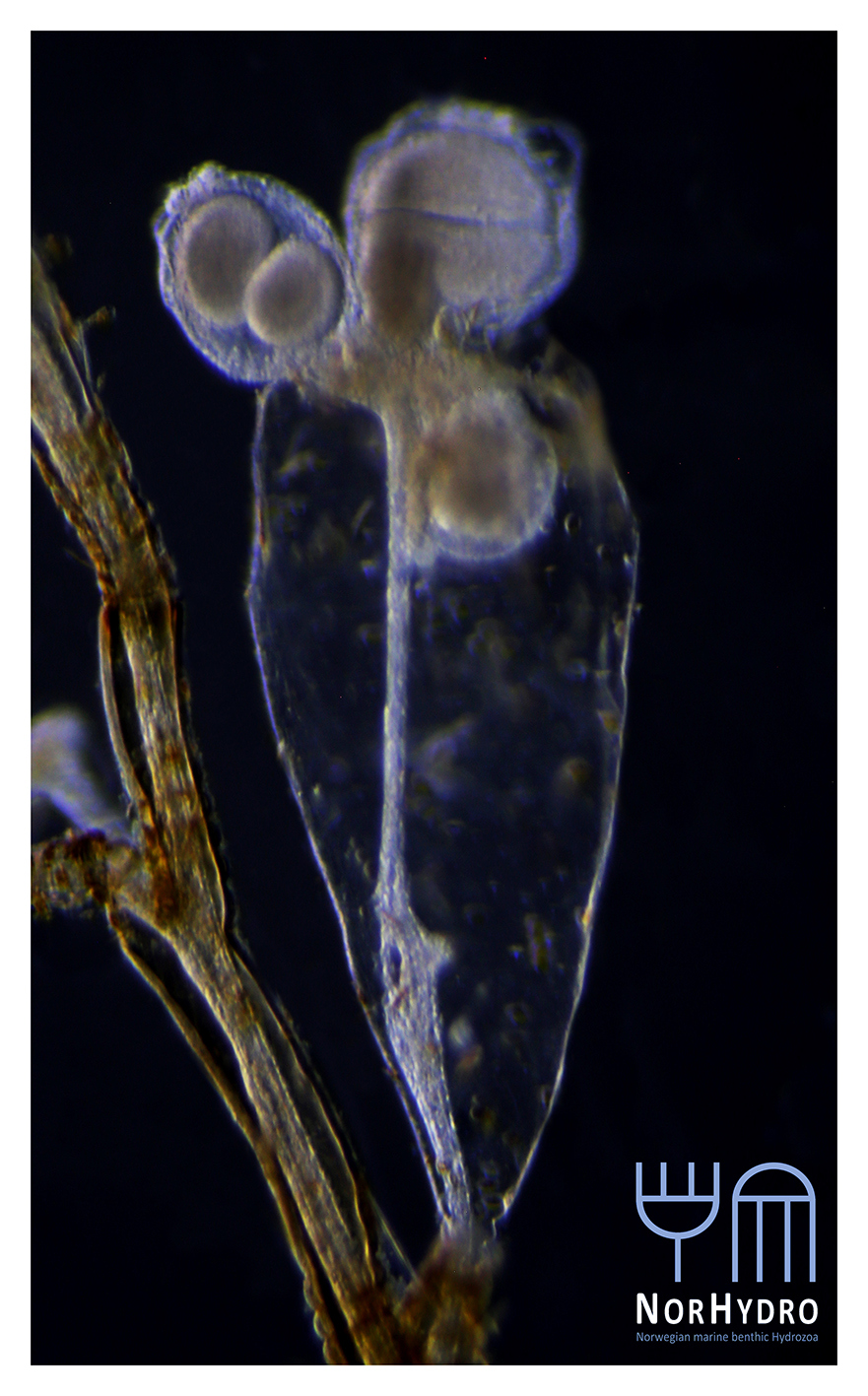

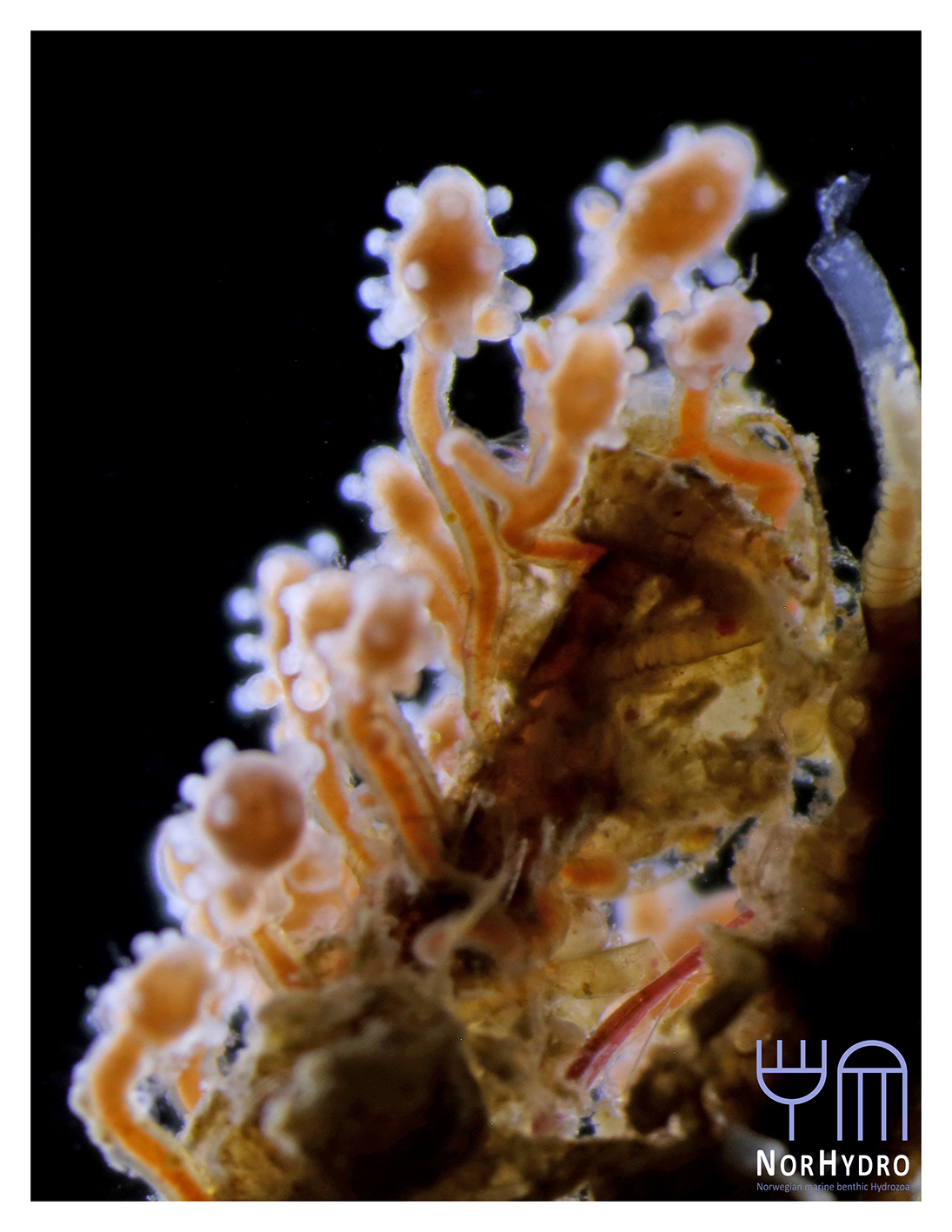

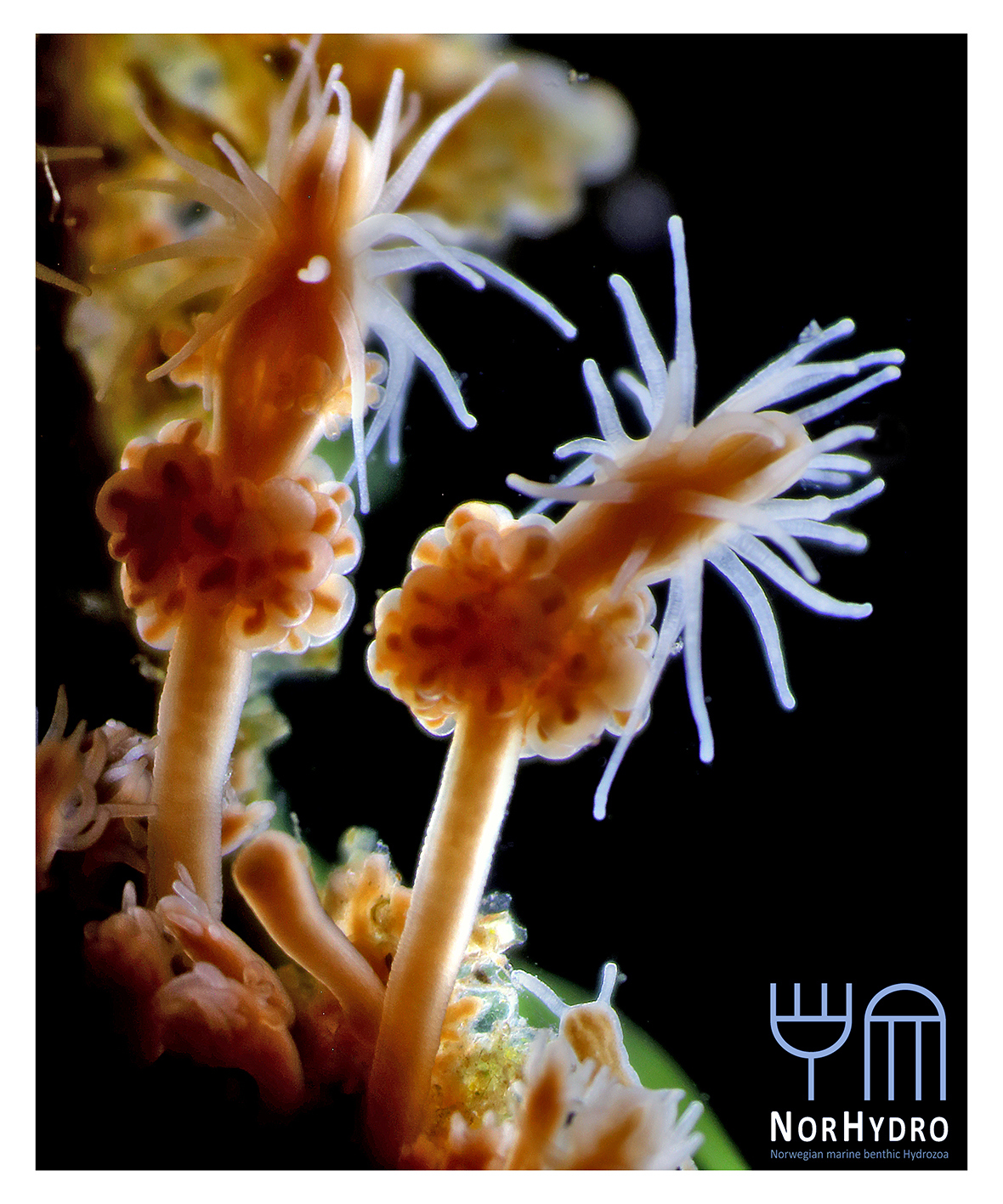

- . One of the exhibits of the aquarium featured some bougainvilliid polyps (and medusa buds) that were being shown to the public with the aid of a camera coupled to a stereomicroscope. That’s exactly how we do it in NorHydro as well!

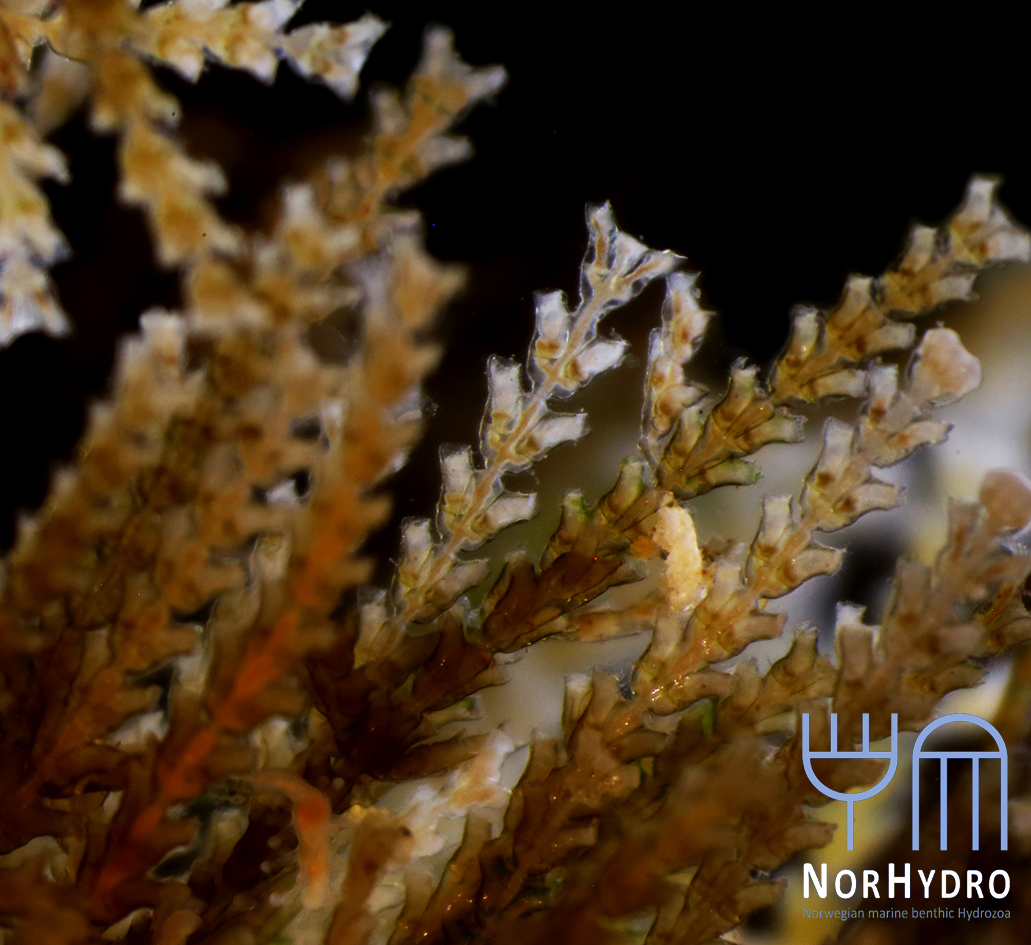

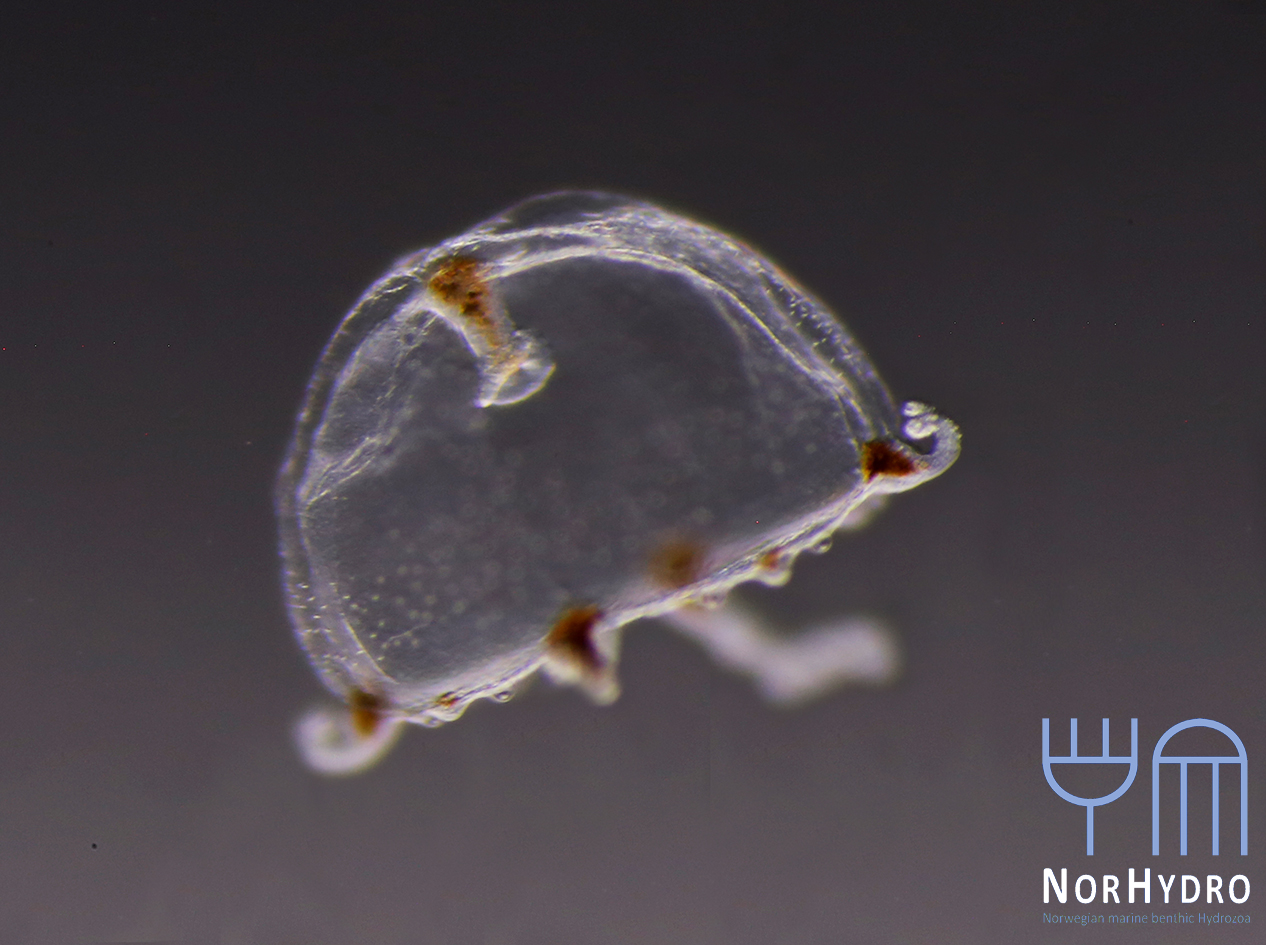

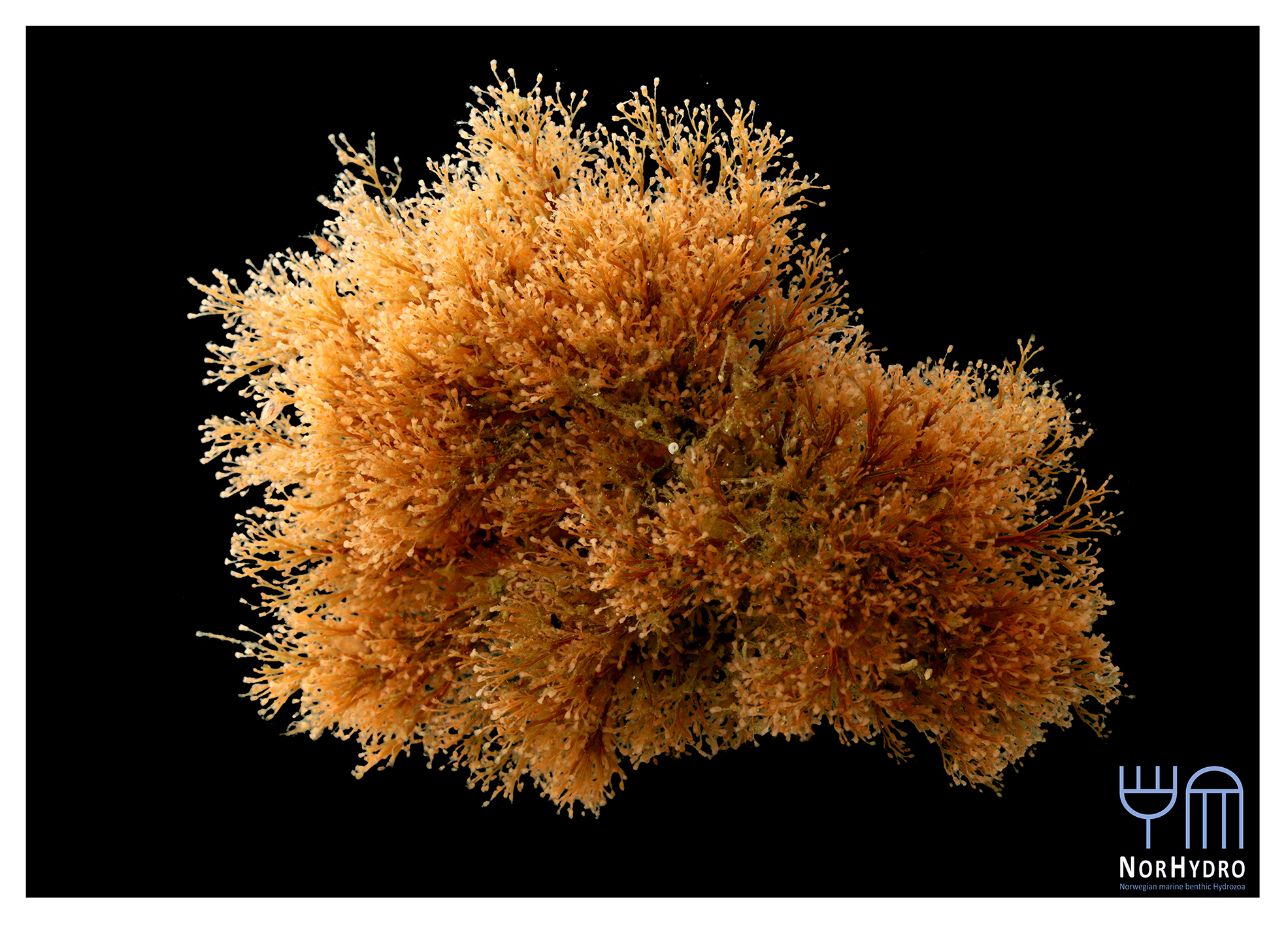

- We were happy to find a hidden hydroid colony (Family Oceaniidae) in one of the tanks of the aquarium.

Overall, the participation of NorHydro in the JBS was very succesful. We received positive feedback about the results presented, and people were very interested in our upcoming activities, particularly the course on hydrozoan biology and diversity (read more and apply here).

NorHydro was so warmly welcomed that we are already looking forward to sharing more about the hydrozoans of Norway in the next JBS in 2022!

– Luis

Keep up with NorHydro in Facebook and in Twitter with hashtag #NorHydro.