This summer I started my master degree project at the University Museum of Bergen and joined the research of Luis Martell and Aino Hosia. I’m a student in the program ‘Biodiversity & Systematics’ at the University of Stockholm and for my 1-year thesis project I wanted to learn more about hydrozoans. Looking for hydrozoan biologists, which there are not so many, I came across the project NorHydro led by Luis and Aino and I decided to go to Bergen to study and learn more about this fascinating group.

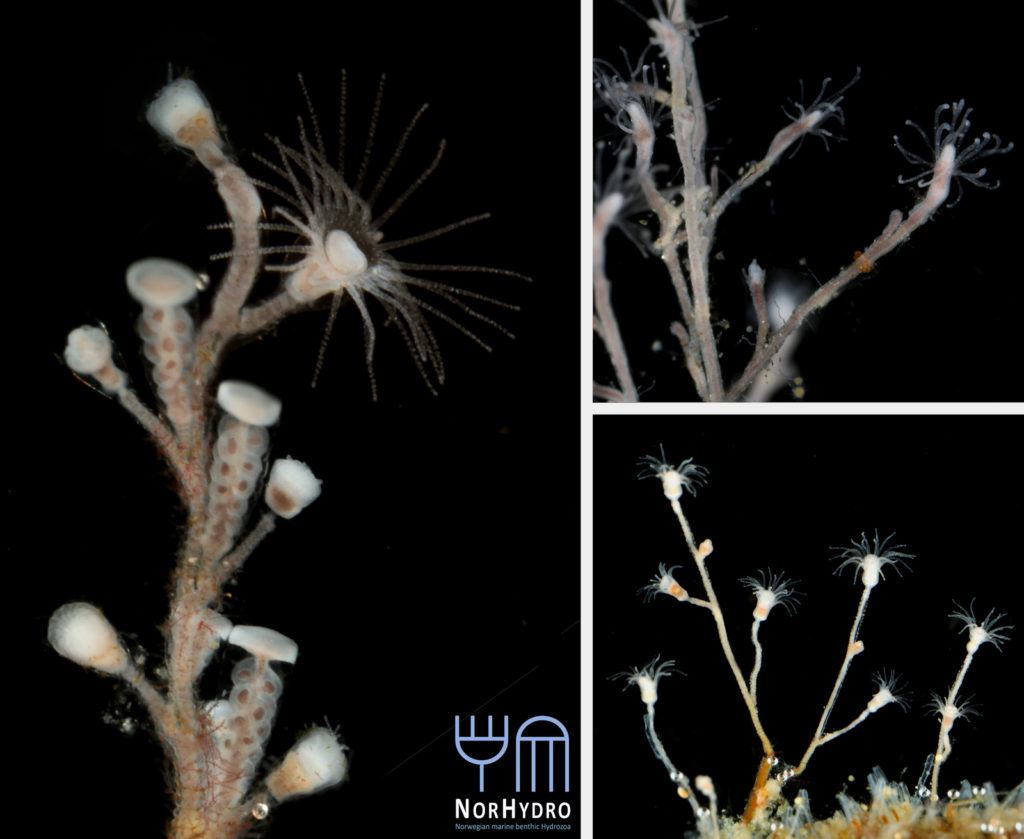

My thesis project especially focuses on the diversity of the hydrozoan family Hydractiniidae. Most commonly hydractiniids are encountered on snail- or hermit crab shells where they can build a mat of polyps. Those shells are often inhabited by other animals and the polyps feed on the left-over meals of those and in return defend their host against predators. With their small tentacles, which are equipped with hundreds of cells containing venomous stingers (the nematocysts) they are great predators and catch tiny animals from the plankton.

Schuchertinia allmanii growing on Pagurus pubescens hermit crab. Picture credit: Bernard Picton

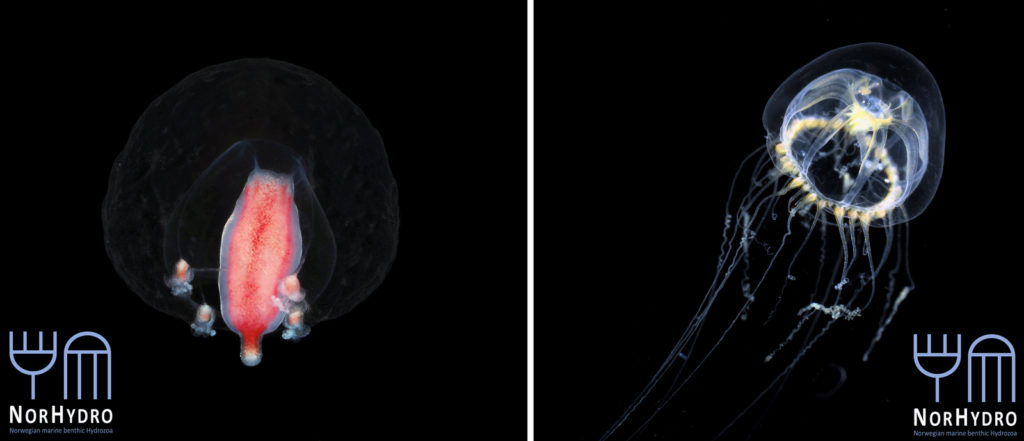

Each individual polyp is connected to each other and build a colony of polyps with different functions. Some act as food suppliers, some as reproductive polyps. From those polyps some hydractiniid species grow tiny medusae (jellyfish) which will be released in the water column. The medusa is morphologically comparable to the polyps, equipped with tentacles, a stomach, gonads and nematocysts – but living upside down and not attached to the sea floor. With their ability to swim around they contribute to disperse themselves in the water and can produce a lot of offspring.

Video of a Pagurus bernhardus hermit crab. A hydractiniid polyp colony is growing on the underside of the shell. Video credit: Lara Beckmann

Several species in this family are often used in development biology or immunology research. For example the species Hydractinia echinata led among other organisms to the discovery of stem cells and is still widely used as a so-called model-organism nowadays. This is because this animal group shows a high ability to regenerate and if you cut a hydroid polyp in two pieces, it will just re-grow again to its initial state.

The life-cycle in hydractiniids can include a polyp and medusa stage. Species of the genus Podocoryna release medusae from their colony. Other genera in this family develop only reduced medusae and lack a free-swimming jelly. Illustration credit: Lara Beckmann

The hydromedusa Podocoryna borealis is released from a polyp colony that can grow on various substrates such as snails or worm tubes. Picture credit: Lara Beckmann.

But despite this spotlight to some species, the diversity of this family is still poorly known and there is little attention to hydractiniid species because of their inconspicuousness and difficult identification. To highlight the problem I did some research: how many and what species are commonly recorded in Norway? Which species could potentially occur in this region according to species descriptions? In private observations and ecological surveys only three species were commonly recorded. However, our preliminary results suggest at least 6 species in Norwegian waters with some surprisingly frequent species that are rarely recorded in surveys. This indicates, that there happens a lot of misidentification in the field and we need to get a better estimate of the true diversity of Hydractiniidae in this region in order to improve awareness and to prevent misidentification in the future.

Two polyps of a colony of the species Clava multicornis. You can see reproductive units (so-called sporosacs) growing on the polyp body, which will release eggs or sperm when fully grown. Picture credit: Luis Martell

In order to do that I study this group in much detail. A great advantage of being a taxonomists in these days is that we can use a variety of different sources of information to develop and test for species hypothesis. This so-called integrative approach includes morphological, ecological and genetical information in order to define taxa diversity from several perspectives.

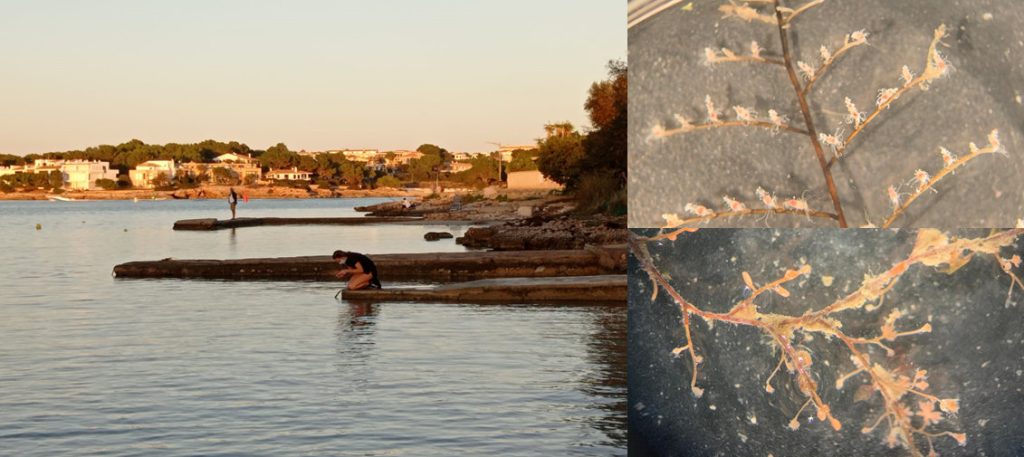

The first step in this process is to gather polyps and medusae of Hydractiniidae from various spots in Norway ranging from Olso, via Bergen and up north to Bodø. I will use already collected samples from previous years and hopefully will also be able to add some more samples from field-trips in the next months.

Getting the plankton-net back on board – and Maryam and me trying to open the jar carefully without spilling the fragile plankton inside. After removing the jar from the net, we directly pick the hydrozoans and put them in a cold environment, so that we can look at them alive when we are back in the lab. Picture credit: Maryam Rezapoor

With fresh material the first step is to take pictures of the living animal. Since hydrozoans tend to shrink and lose a lot of it characteristic traits in the ethanol preservative it is important to take pictures right away when the animal is still alive. Furthermore the samples are identified using a microscope, identification keys and additional literature. With additional collected data such as habitat, location, sample depth and so forth we create a large database for our samples and develop so-called e-vouchers: an electronic data storage for each individual to ensure to gather and store as much information as possible. That makes it possible to go back to the database and look at the specimen data e.g. where did it live? On what substrate was it growing on? How deep was the sampling site? This way I don’t only rely on the preserved material but can easily use the e-voucher material and the additional collected data that can be useful for further analyses.

Besides the morphological and ecological data I also include molecular information: what does the DNA tell us about the specimen? For that I use three different genetic markers (short DNA fragments, or genes) to see how those differ in their sequence of bases between the sampled hydractiniid specimen. In the course of evolution, DNA sequences change due to selection, genetic drift, gene flow and random mutations. That is why we are able to infer evolutionary relationships between biological entities – in this case we are interested in species – and with mathematical models and some simplified assumptions we can delimit species based on their molecular attributes.

Me in the DNA lab waiting for the first results of lab work for this project! Picture credit: Maryam Rezapoor

In order to do so, I will process the sampled material in the lab. First, I extract the DNA from a tiny piece of polyp or medusa tissue and then amplify the specific target region using PCR (Polymerase-Chain-Reaction). This short DNA fragment will further be sequenced which outcome I will check, process and analyze using different computer programs and algorithms. The final results will be summarized and visible in so-called gene trees, revealing the evolutionary history of those three different DNA markers. I will use the gene genealogies to delimit the species and observe how much diversity of hydractiniids we have in Norway.

Using specific genes also facilitate us with species barcodes which are used to create a reference library. This in return enables researchers to identify a specimen without the need to identify the sample using its morphology. This can be the case e.g. for metabarcoding projects (sequencing a mass of DNA from unknown origin) or if samples are unidentifiable. The scientist will then sequence the barcode gene and compare it to the reference library and will eventually be able to tell the species. Those barcodes can be informative in biodiversity studies but by no means substitute taxonomists, which are still needed to describe and identify species when no DNA is available.

A monograph of the Gymnoblastic or Tubularian hydroids by George James Allman, published in 1870. I found this book in the library of the Tjärnö laboratories in Sweden. Allman was a pioneer in hydrozoan research and described many species. Nowadays it is much easier to access original descriptions since many book are available online. You can find a PDF* of this book in the Biodiversity Library. Picture credits: Lara Beckmann

Also, the DNA does not help us when we have no reference we can map the specimen to in order to determine the species. That is why this master project also aims to create a barcode-library for the species in the family Hydractiniidae.

What I really like about this project is that it contributes to our basic understanding of the diversity in our oceans – in this case even in two completely different environments: the water column as well as the seafloor.

Even if hydractiniids are just a little part of the ecosystem, they play their role and influence the ocean in their own way. Also, my work is super diverse and I need to be an allrounder in many respects: trying to find species descriptions I search and read taxonomic literature from the 19th century (coming in Latin, German, English, Swedish or French). Then I work in the laboratory where I combine traditional working methods like drawing, microscopy or photography with modern techniques from DNA sequencing to computational science and bioinformatics.

I love this kind of work, and it is great to contribute just a little bit to reveal the mysteries of our oceans.

– Lara

You want to learn more about hydrozoans and why it is important to study them? Read more about it in my blog article for Ecology for the Masses (link).

Also, keep up with the activities of NorHydro (link to project home page) here in the blog, on the project’s facebook page (link) and in Twitter with the hashtag #NorHydro.

*Link to pdf of A monograph of the Gymnoblastic or Tubularian hydroids by George James Allman