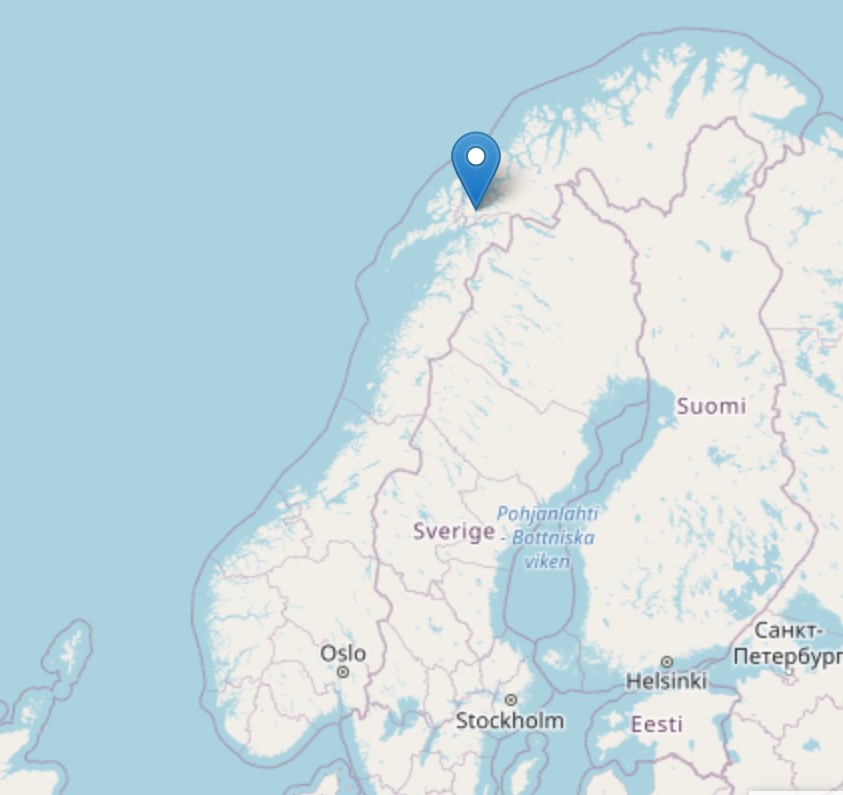

From Monday 12th of October till Monday the 19th a bunch of different projects funded by the Norwegian taxonomy initiative travelled up North together to meet up with researchers from NTNU in the NTNU Sletvik field station.

Sletvik fieldstation is NTNU owned and is a short drive from Trondheim. The Germans built the station during the Second World War. Ever since it has been used as a town hall, a school and a shop. In 1976 the NTNU University took over the building and transformed it into a field station, which it remains ever since. The entire station contains of two buildings that has room for a total of 75 people (Before Corona). The main building has a kitchen, dining and living room plus a large teaching laboratory, a multilab and two seawater laboratories. Besides it has bedrooms, sauna, laundry rooms, and showers, fully equipped! The barracks have additional bedrooms and showers, all in all, plenty of space.

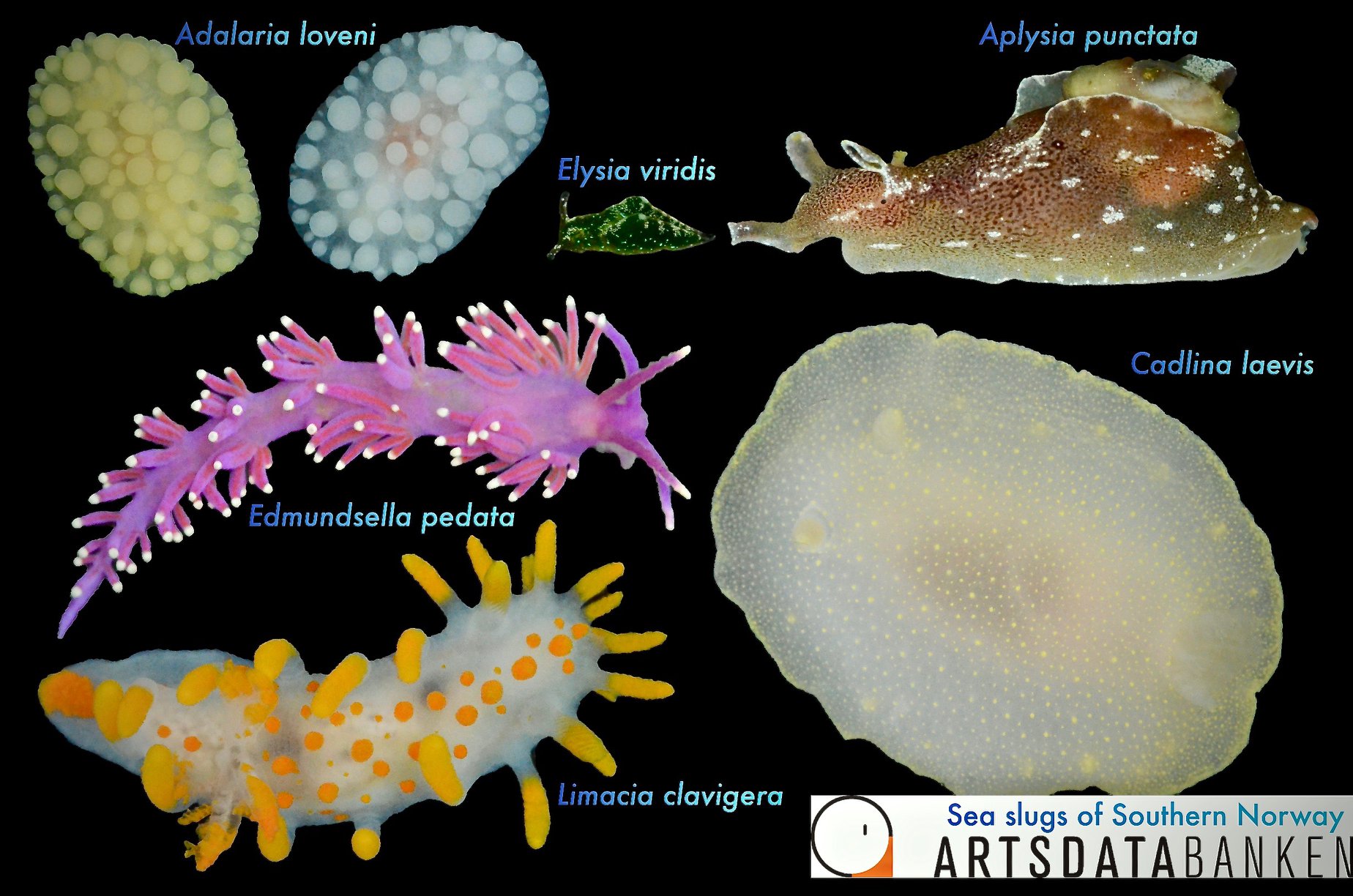

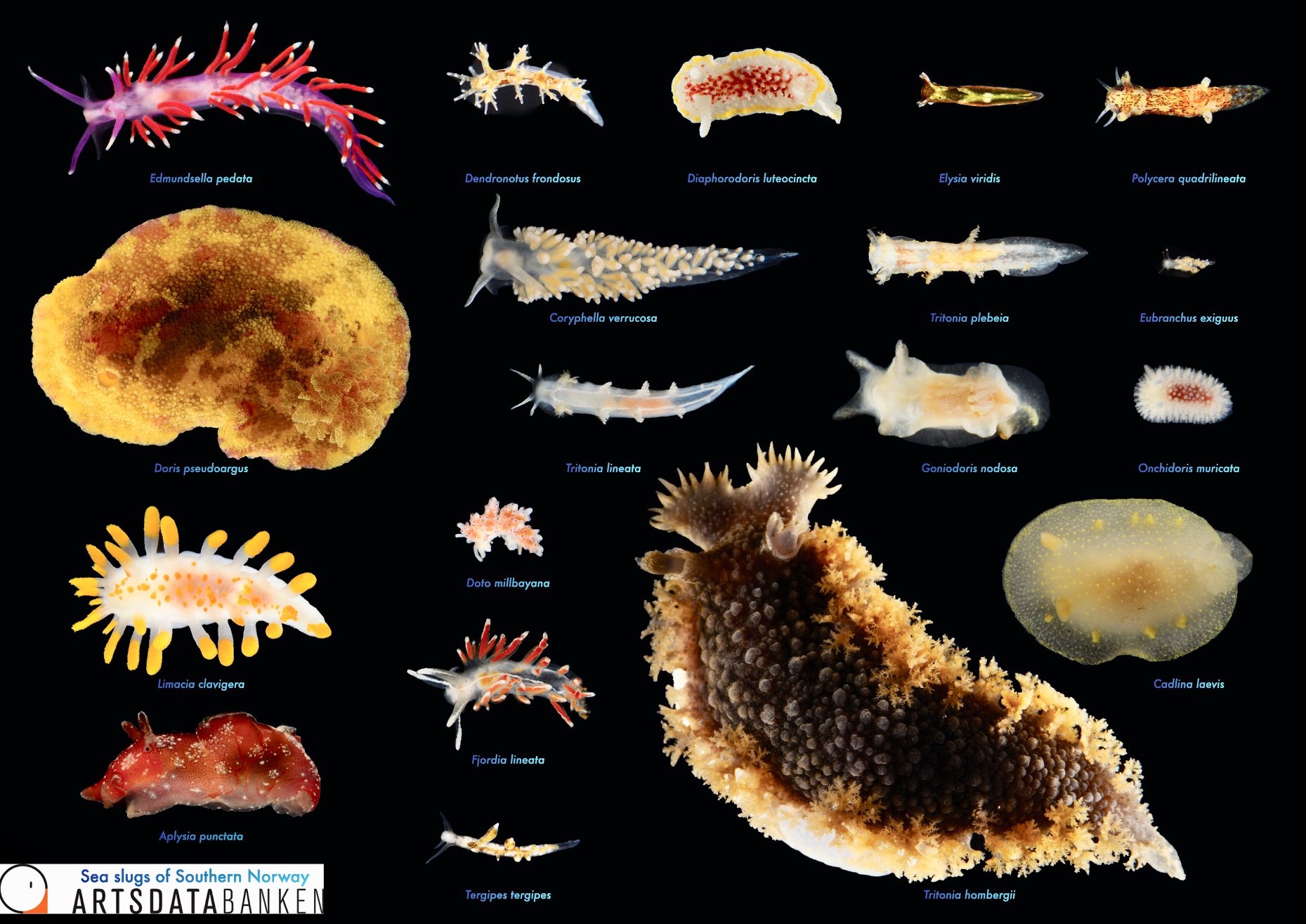

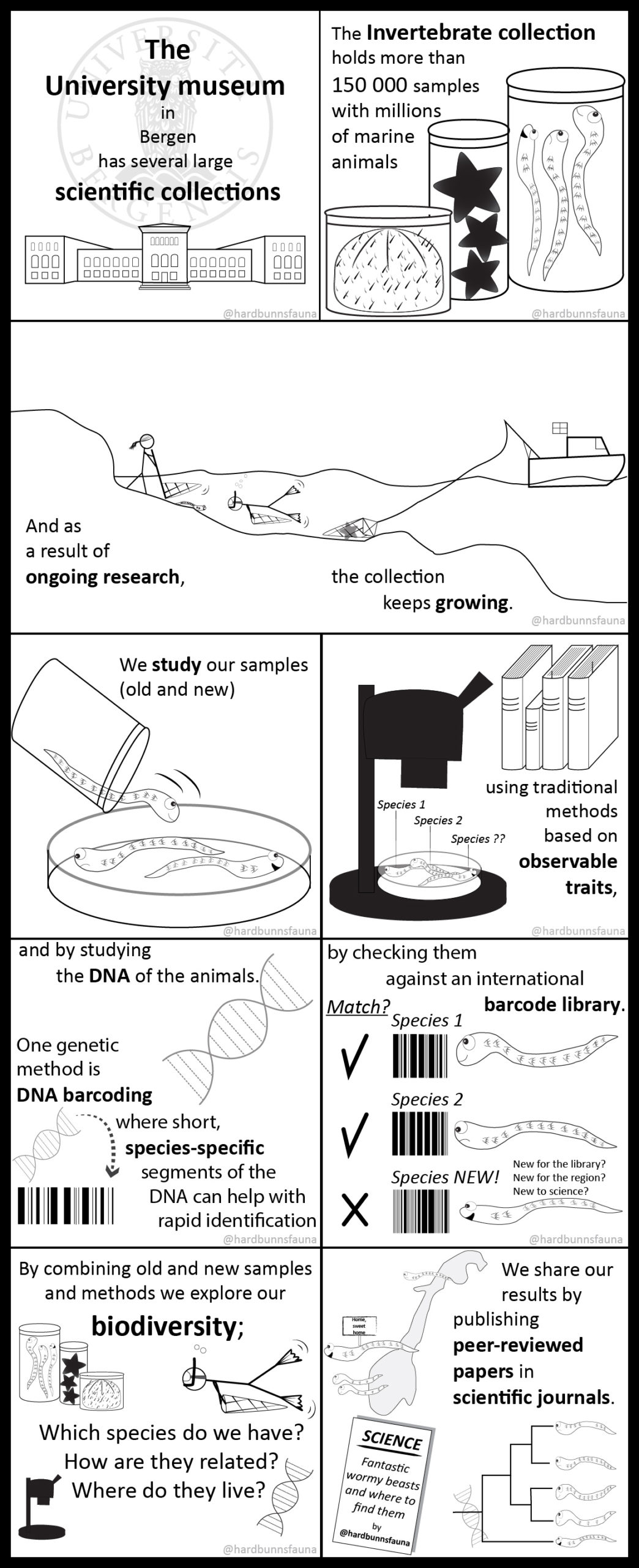

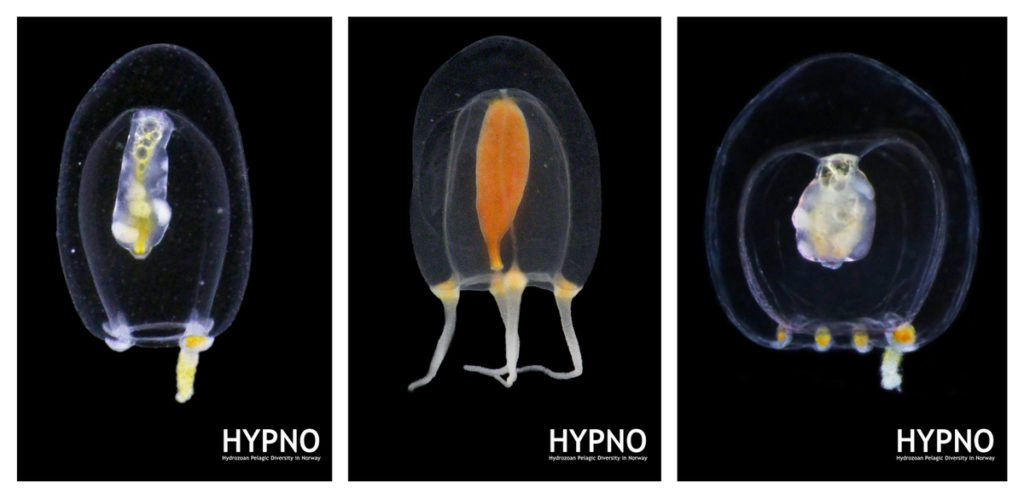

From the Natural History Museum of Bergen, 5 current running projects would use the NTNU fieldstation facilities for a week in order to work on both fixed as well as fresh material. Besides HYPCOP (follow @planetcopepod), we had Hardbunnsfauna (Norwegian rocky shore invertebrates @hardbunnsfauna), Norhydro (Norwegian Hydrozoa), Norchitons (Norwegian chitons @norchitons) and NorAmph2 (Norwegian amphipods) joining the fieldwork up North!

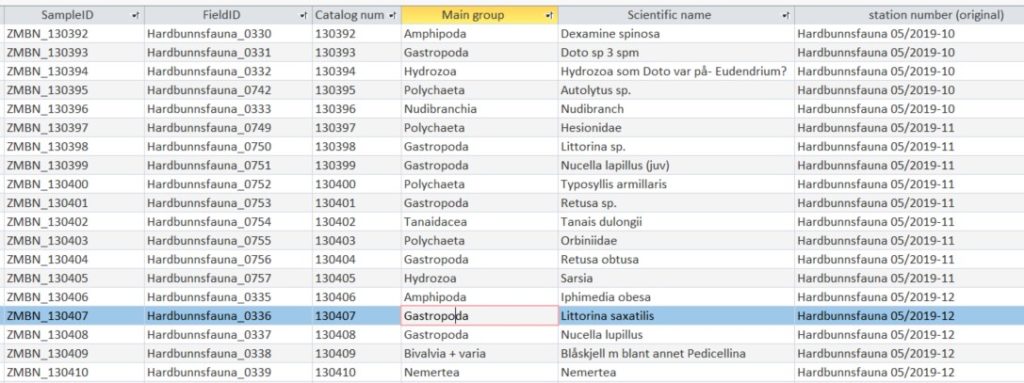

At the Sletvik fieldstation, a lot of material from previous fieldwork was waiting for us to be sorted.

For HYPCOP we wanted to focus mostly on fresh material, as this was a new location for the project. And not just new, it was also interesting as we have never been able to sample this far north before. Almost every day we tried to sample fresh material from different locations around the fieldstation

On top of that we aimed to sample from different habitats. From very shallow heavy current tidal flows, rocky shores, steep walls, almost closed marine lakes (pollen called in Norwegian) and last but not least, sea grass meadows

Sampling we did by either dragging a small plankton net trough the benthic fauna or the most efficient way, going snorkeling with a net bag

Benthic copepod species tend to cling on algae and other debris from the bottom, so it is a matter of collecting and see in the laboratory whether we caught some copepods, which, hardly ever fails, because copepods are everywhere!

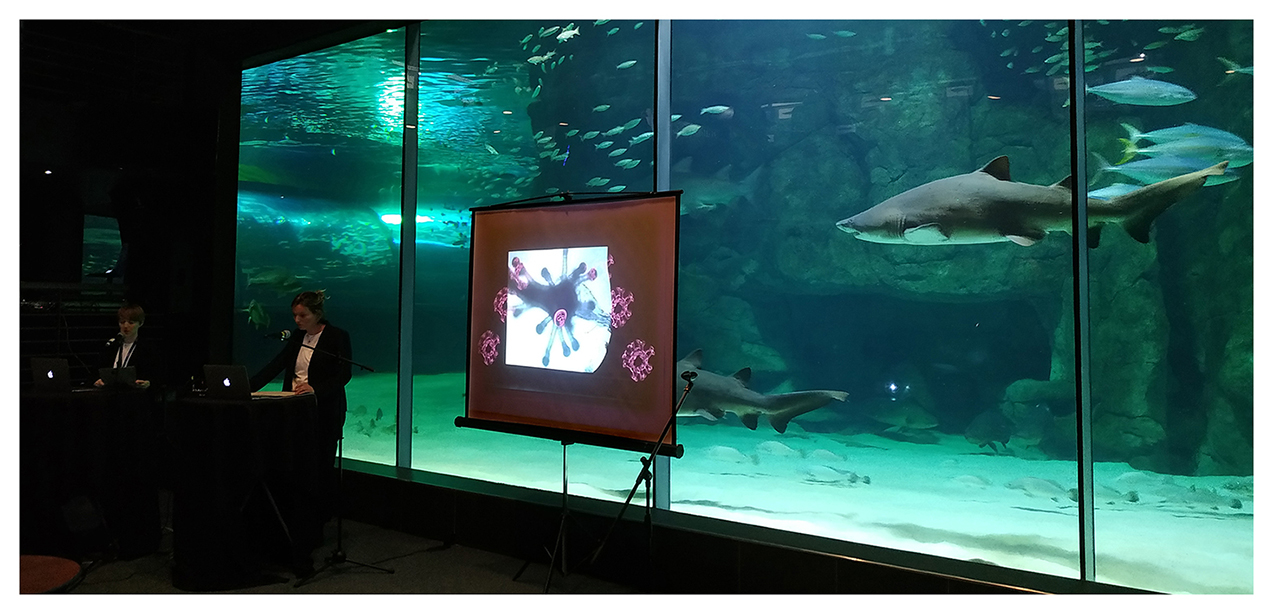

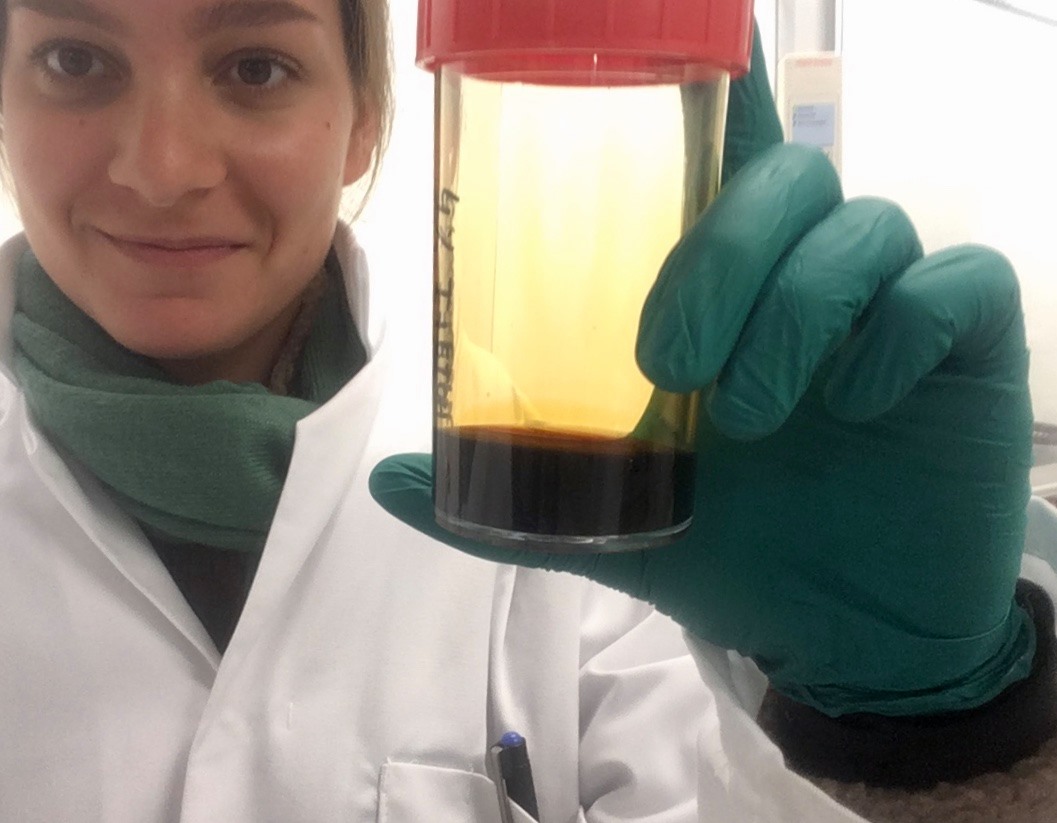

Copepods are difficult to identify due to their small nature, differences between males, females and juveniles’ and the high abundance of different species. Therefore, we rely heavily on genetic barcoding in order to speed up the process of species identification. So, after collecting fresh material, we would make pictures of live specimens to document their unique colors, and then proceed to fixate them for DNA analyses.

The other projects had a similar workflow so you can imagine, with the little time we got, the Sletvik fieldstation turned into a busy beehive! One week later we already had to say goodbye to the amazing fieldstation, and after a long travel back (even with some snow in the mountains), we finally arrived back in Bergen where unmistakably our work of sorting, documentation and barcoding samples continued!

If you are interested to follow the projects activity, we have social media presence on Twitter (@planetcopepod, @hardbunnsfauna, @norchitons), Instagram (@planetcopepod, @hardbunnsfauna, @norchitons) and Facebook (/planetcopepod /HydrozoanScience).

-Cessa