Travelogue from Cessa Rauch

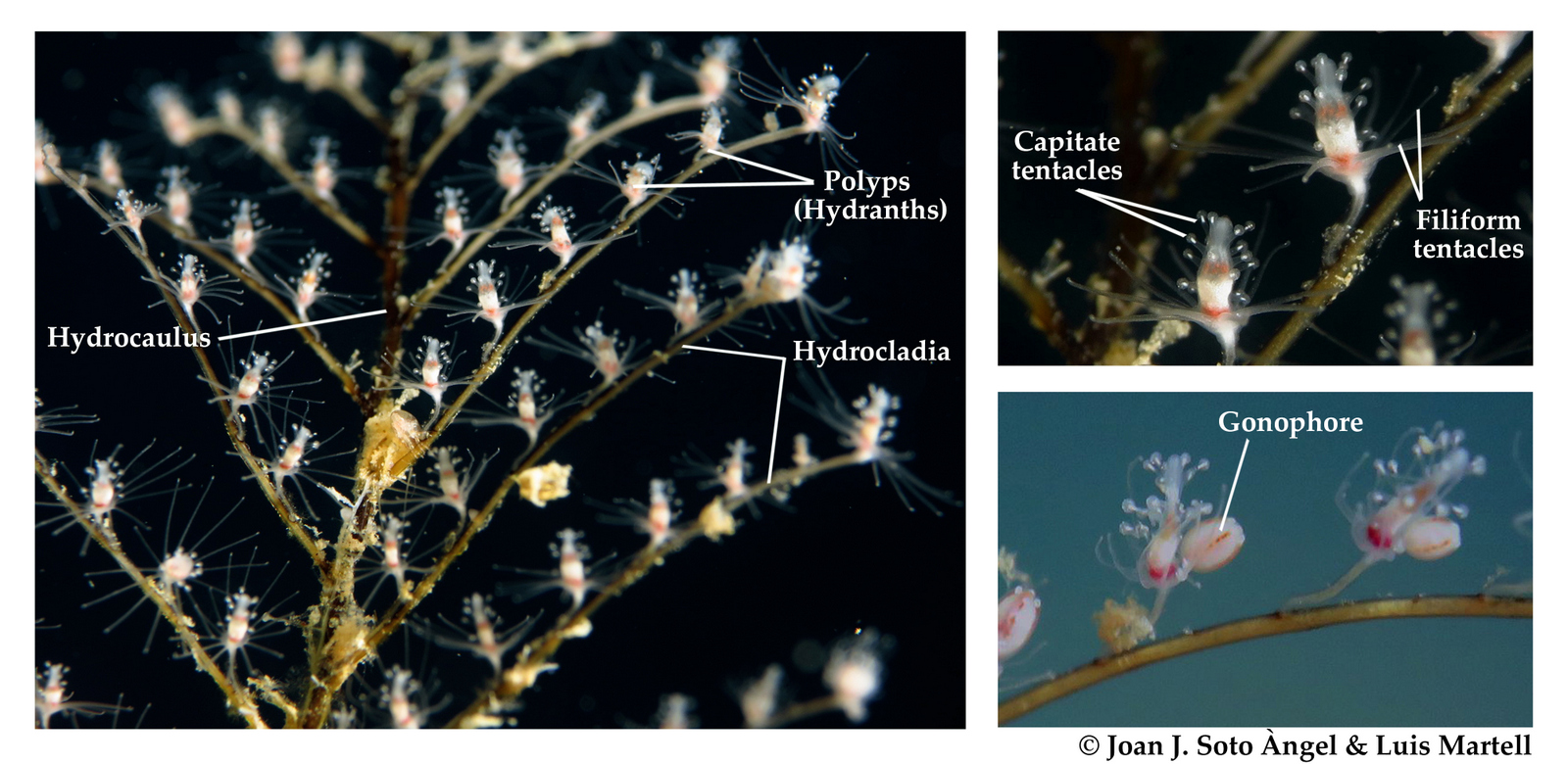

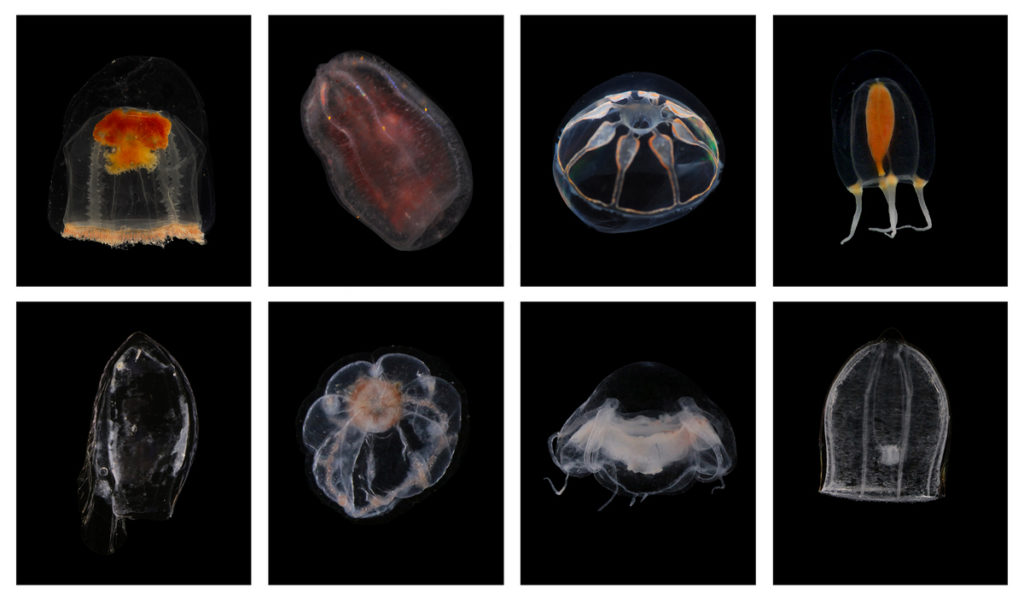

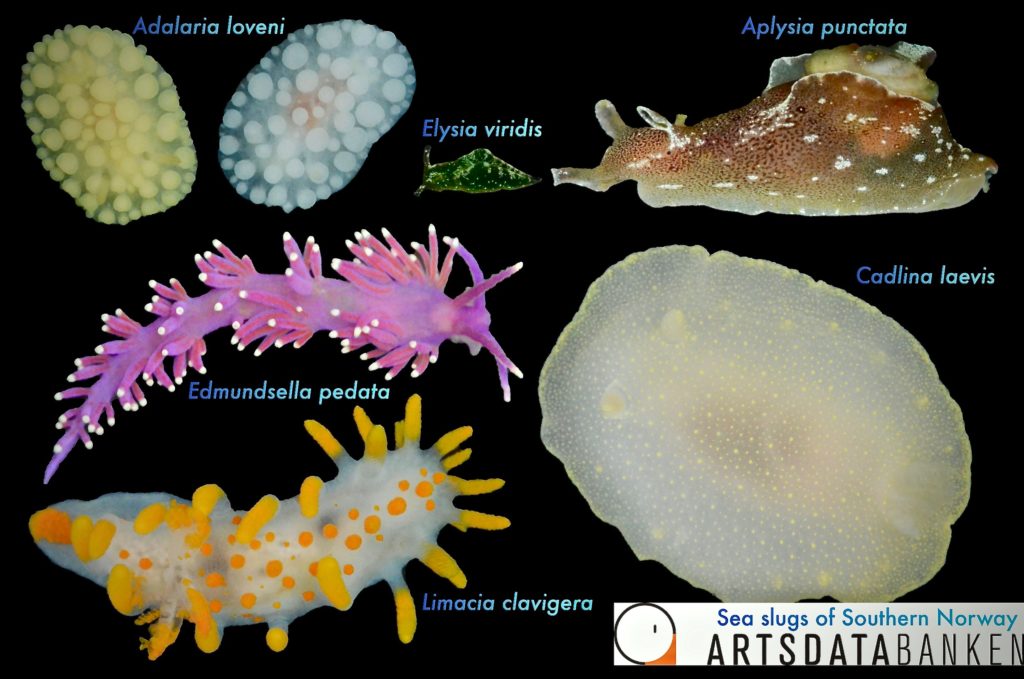

Today the weekly event of MolluscMonday and the annual SeaSlugDay (29th of October) coincide! Bunch of sea slugs to celebrate sea slug day, collected in Askøy

Bunch of sea slugs to celebrate sea slug day, collected in Askøy

What better way to celebrate it with another blog! Much has happened again since the last blog in August, in which we went on fieldwork in Askøy by joining the ladies of the jentedykketreff to find sea slug species in the Bergen area. We officially started to barcode our first specimens, got two new master students that will also work on the project by looking into a variety of topics (diversity of sea slugs in Hordaland, population genetics of Polycera quadrilineata and taxonomy of the genus Eubranchus).

In this blog I will share with you how we are uploading our slugs to the World Wide Web with help of the Barcode of Life data system and how the Norwegian Barcode of Life is helping us getting this done by organizing an informative course in Trondheim.

First step in trying to decode our precious species

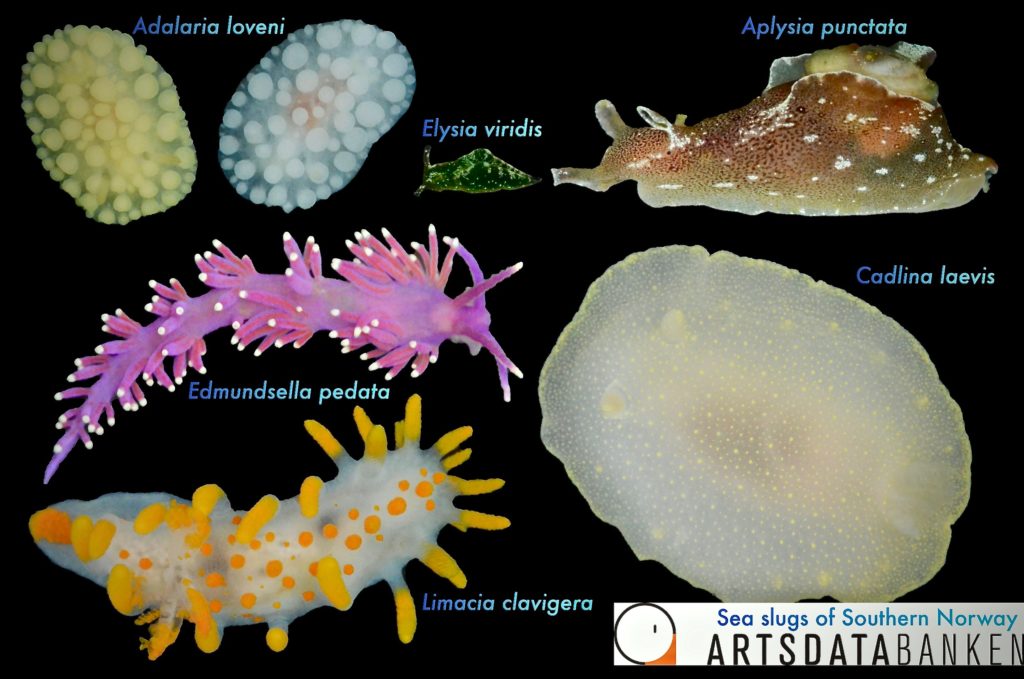

The sea slugs of Southern Norway project is a two-year project funded by Artsdatabanken (The Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative) with the aim of mapping the biodiversity of sea slugs along the Southern part of the Norwegian coast

Sea slugs of Southern Norway being eaten by Doris pseudoargus

The focal area stretches from Bergen, Hordaland, all the way down to the Swedish border. In May, July and August of this year the project successfully completed its first fieldwork trips with an additional of 500 new registered museum specimens that cover roughly 90 sea slug species. The species names are attributed based on morphological characteristics, but several species exhibit amazing colour polymorphism, possibly hiding cryptic diversity.

Moreover, we cannot discard the possible occurrence of alien species with similar morphotypes to the native fauna. Therefore, we will need to DNA barcode our specimens to either confirm or change the species names credited to our collected specimens. Besides it will give us an overview for the relatedness of the sea slugs to one another and unravel maybe new species!

In order to successfully sequence 500+ specimen the project collaborates with the Norwegian Barcode of Life project (NorBOL). NorBOL is a network of Norwegian biodiversity institutions and individual scientists that coordinates the establishment of a library of DNA sequences (barcodes) of the fauna and flora of Norway. These barcodes)will be submitted to the open access database BOLD (Barcode of Life Data System), as part of the global Barcode of Life initiative and the International Barcode of Life project (iBOL).

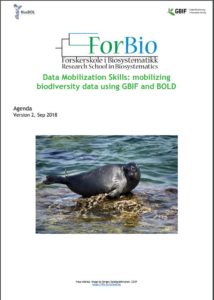

Barcode of Life Data System course

Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) is a globally orientated online workbench and database that supports the assembly and use of DNA barcode data, and is open access to the scientific community and public. At the moment it holds a record of 6235000 barcodes; 194000 of those are animal species, 67000 plant species and 21000 fungi and other species. The BOLD system is an amazing tool to work with for those interested in biodiversity research. Initially it can be a little overwhelming to fill in all available data into Excel file after Excel file, as this is mandatory and needs to be uploaded first to the system before any sequencing can be done. Especially for those who have many specimens to work with. But afterwards the reward is very fulfilling as you, in an instant, can see distribution maps, trees and images of all the specimens uploaded.

Distribution map from Google earth with collected sea slugs from the Oslo area

Image library of all the collected sea slugs

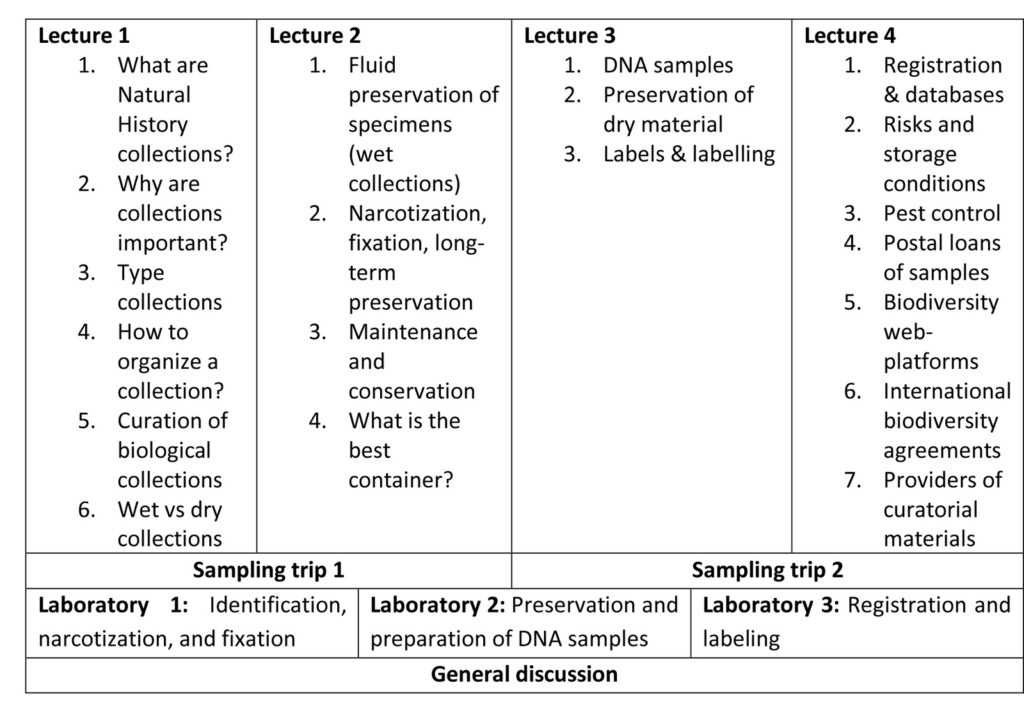

It is the perfect tool for digitizing, analysing, storing and accessing your genetic and image library data from everywhere anytime. BOLD system standards for uploading actual specimen data are pretty high, the quality of what you can find on the platform is good, but in order to keep these standards great, NorBOL organizes special multi day courses for users in order to guide them through all the steps and features of the BOLD system. This year the course was organized by the NorBOL National coordinator NTNU in Trondheim.

It would take three full days of getting together with fellow participants and going through all the steps necessary in order to start a successful project in the BOLD platform. This year it took place from 17th till 19th of October and as such, me, Anna and Per travelled that Wednesday the 17th very early in the morning to Trondheim. The course was well attended with participants traveling from all over Norway and even from its neighbouring country Sweden. The first day consisted mainly of introduction talks and familiarizing ourselves with the many new abbreviations; NorBOL, BOLD, iBOL (et cetera).

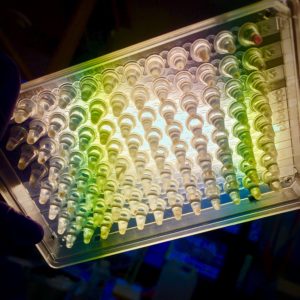

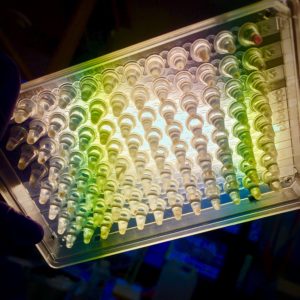

It was a nice experience to meet and talk to other biologists working on such interesting topics, varying from flies, mites, sponges, jellyfish, worms, variety of plants, etc. Everything was taken care off, we could check in to our hotels and in the evening, we had a dinner together with the organizers and participants. The next two course days we were asked to work with our own brought specimens. The days consisted of registering the specimens, filling in as much data per specimens as possible. After finishing and uploading the first datasets, it was time to make pictures of every species, before sampling them for DNA barcoding tissue. Almost all participants brought a 96 wells plate worth of specimens so you can imagine the work that was put into getting everything finished in such a short amount of time.

Sea slug tissue in a 96 well plate ready to be shipped for barcoding

The course was an excellent way to get used to the different steps necessary in order to make the submission process a success. And it was very helpful that at any given moment we could ask the course organizers for advice during the preparations of the datasets and the submission.

All the participants were very excited about the course and happy they attended, it was nice meeting new people and as for someone that moved to Norway, a good opportunity to finally also see Trondheim, with its amazing large Cathedral, a real eyecatcher

-

-

Trondheim Cathedral in all its glory

-

Sea slug goals

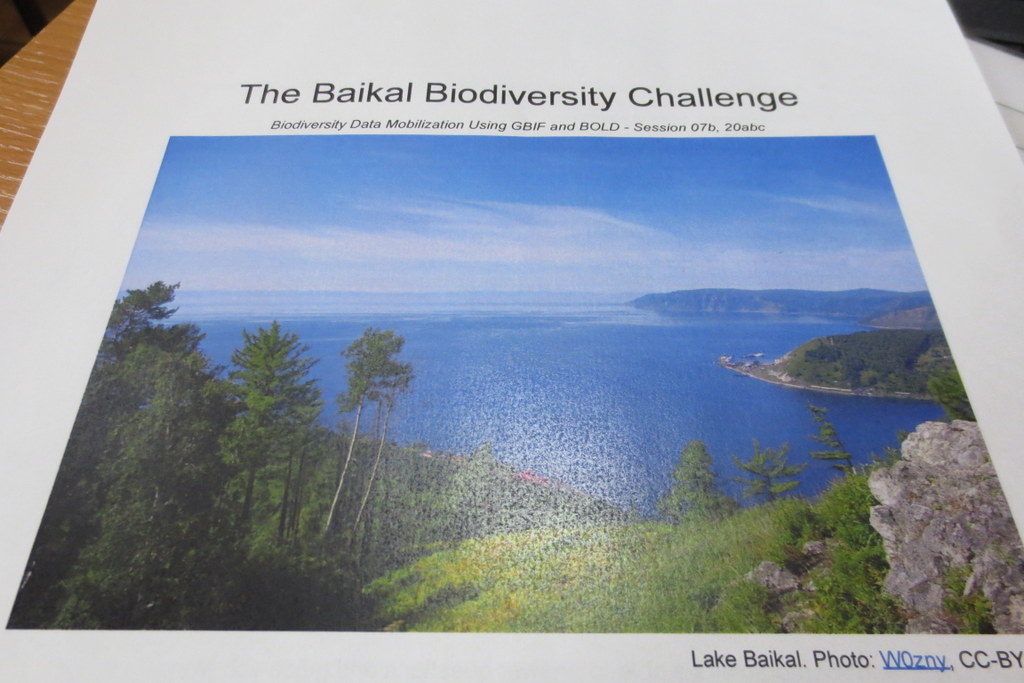

The goal for the sea slugs of Southern Norway project is to barcode all, or at least as much as possible, collected specimen, in order to attribute species names to them, expose cryptic species, maybe find new species and look out for invasive and or alien species. Thanks to this course the first 95 species will be barcoded soon and be added to the image library that we already managed to set up (Image 8. Screenshot of the project page of sea slugs of Southern Norway in the BOLD system workbench).

Screenshot of the project page of sea slugs of Southern Norway in the BOLD system workbench

We are very much looking forward for the first results to be accessible and to analyse the data; keep an eye on the invertebrate blogs because for sure the follow up of this story is going to be pretty exciting.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Aina Mærk Aspaas for the coordination of the course, Katrine Kongshavn to help out with my first introduction to NorBOL and the BOLD system workbench and Anna Beata Seniczak and Per Djursvoll for being great colleagues during the course and lovely companions in discovering Trondheim together as real Bergen tourists!

Furthermore

Sea slugs of Southern Norway recently got its own Instagram account! Perfect for on the go if you would like to quickly check some species or just want to look at pretty pictures; click here, and don’t forget to follow us.

Sea slugs of Southern Norway recently got its own Instagram account! Perfect for on the go if you would like to quickly check some species or just want to look at pretty pictures; click here, and don’t forget to follow us.

Curious about what we have been doing so far, read about it in our blogs on the invertebrate website;

First fieldwork blog Drøbak may 2018;

Second fieldwork blog Haugesund July 2018;

Third fieldwork trip august 2018

Become a member of the sea slugs of southern Norway facebook group, stay updated and join the discussion; https://www.facebook.com/groups/seaslugsofsouthernnorway/

Why is it SeaSlugDay today? Read more about that here! (link goes to Echinoblog)

Explore the world, read the invertebrate blogs!

-Cessa