Earlier this year, the Cnidaria and Ctenophora group at UMB organized the 10th International Workshop of the Hydrozoan Society. The event was a success, and we asked visiting researcher Marta Gil to tell us a little more about it.

This is what Marta, who is currently collaborating in our Artsdatabanken projects ParaZoo and NOAH, has to say:

Hello to everyone!

I’m Dr Marta Gil, a researcher at the association Ecoafrik and a member of the Marine Zoology Group at the University of Vigo, Spain. This spring I began a research stay at the University Museum of Bergen to collaborate with Dr Luis Martell on project PARAZOO. I have visited the museum several times, but this visit had a special meaning for me. This year, in May, the 10th Workshop of the Hydrozoan Society was celebrated, organised by the Cnidaria and Ctenophora Group at the Department of Natural History, so I took advantage of my stay in the city and decided to attend.

This was my first time at this event and I must say it was a very rewarding experience, I don’t think I could have enjoyed it more. We were welcomed by the organisers at the public collections of the Natural History Museum, which was open only for the occasion, creating a fantastic atmosphere to meet the participants and many of the hydrozoan experts.

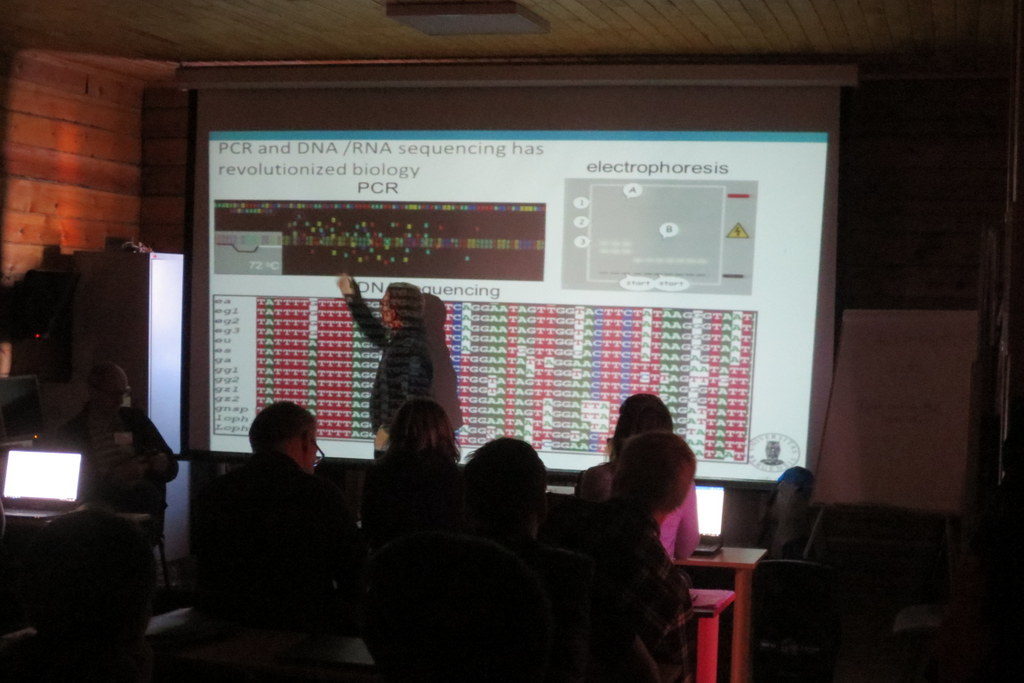

Over the next three days, we listened to talks from students who are just starting as well as presentations from established researchers who have been working with hydrozoans for years. We have had great speakers such as Dr. Nicole Gravier-Bonnet, Prof. Carina Östman, and Dr.Gill Mapstone; and how to forget the enthusiasm of Prof. Paul Bologna’s group, all the questions and remarks from Dr. Dhugal Lindsay, and the sampling demonstration from our Japanese colleagues Gaku Yamamoto and Aya Adachi? The discussions that took place after each talk and the engaging poster session made this workshop more than a simple scientific meeting, it was a group of friends talking about their favourite animal group: hydrozoans!

The conference part of the Workshop brought many interesting talks from a wide array of topics, together with fruitful and interesting discussions and networking.

There was a dedicated poster session (and catering) to further discuss about hydrozoans in a more relaxed environment. Many great projects and preliminary results were presented!

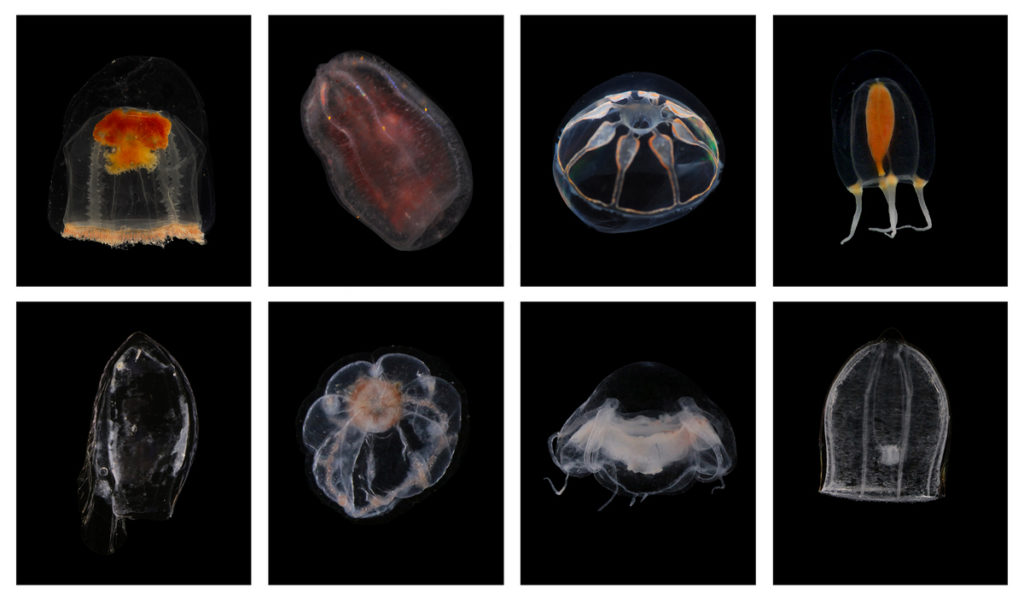

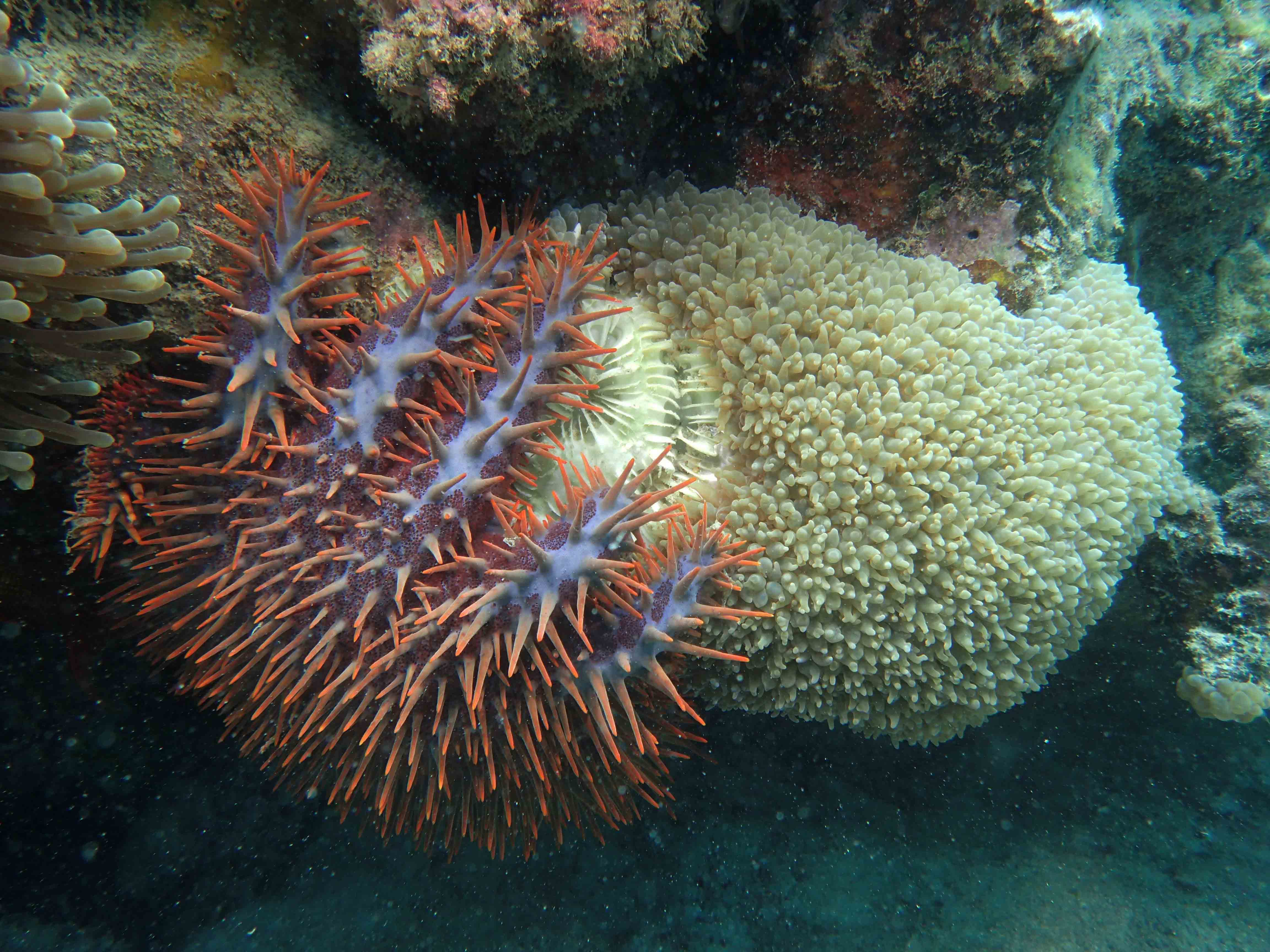

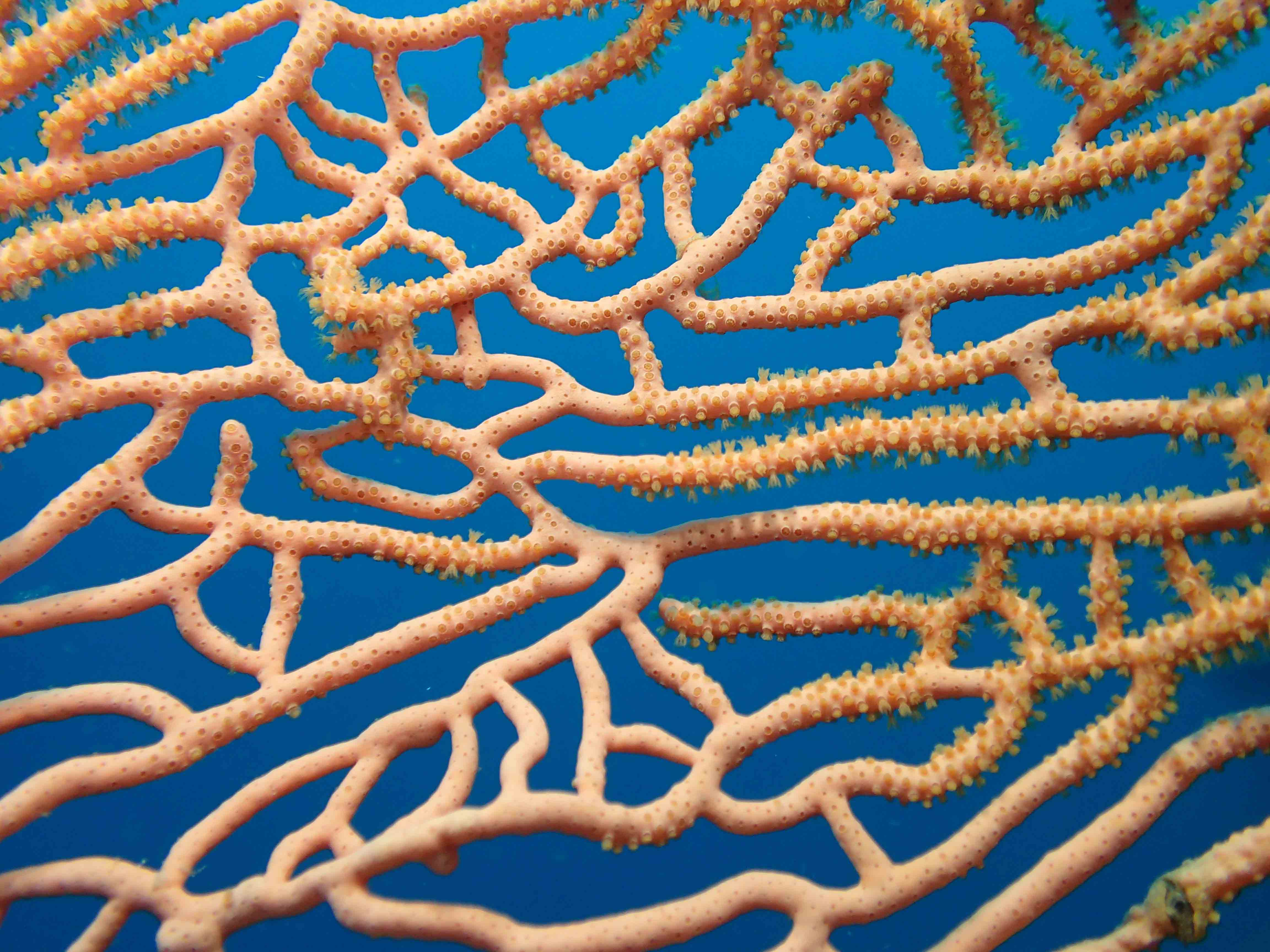

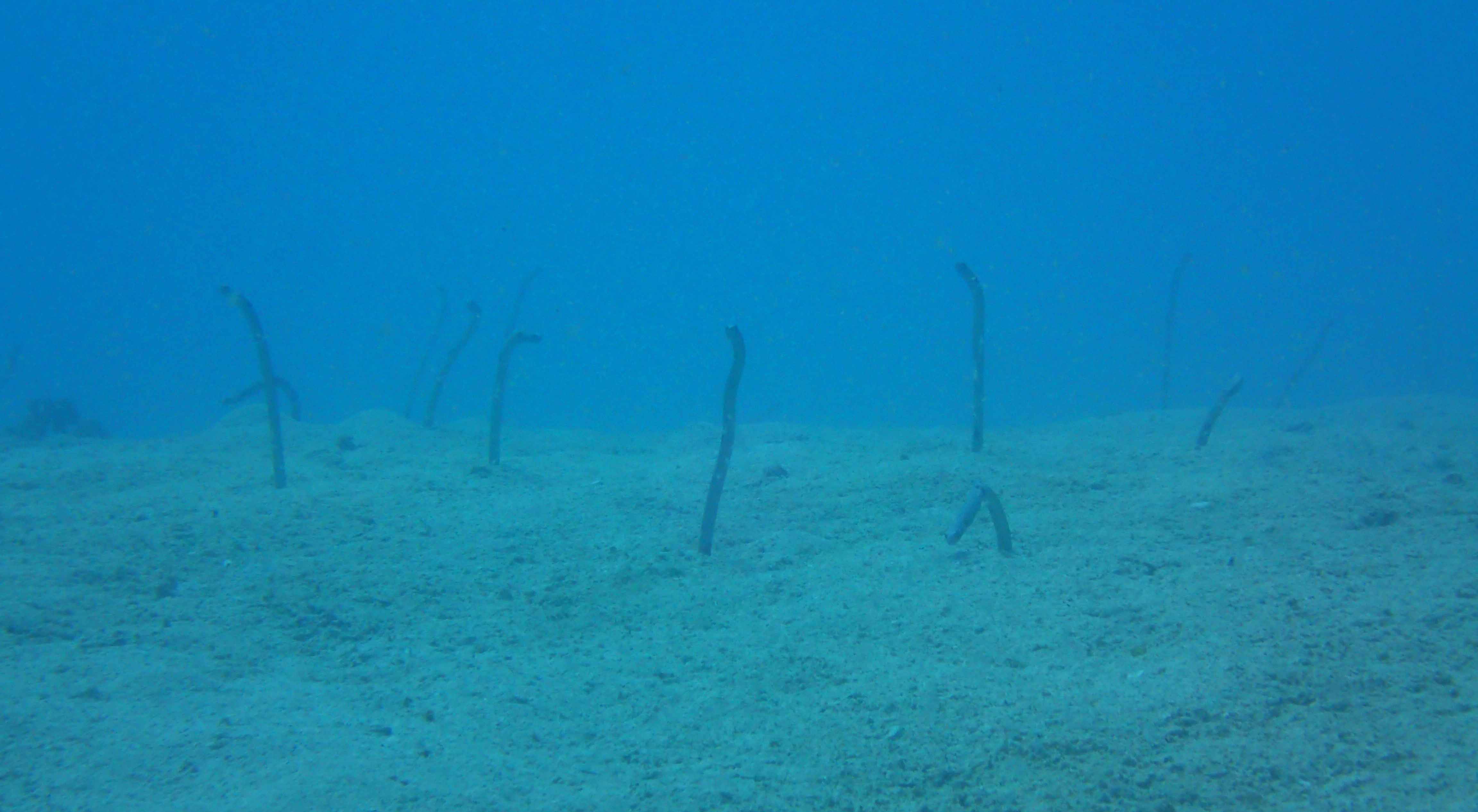

After the talks and presentations were over, the sampling part started, which was the most fun for me! We were able to sample benthic hydroids and pelagic hydromedusae and siphonophores on board the Emiliania and the R/V Prinsesse Ingrid Alexandra, and we later studied them at the Espegrend Marine Biological Station. This part gave us the opportunity to learn and share knowledge, techniques and very useful tips from other experts to study hydrozoans throughout their life cycle.

Two busy samplings days followed the conference part, where we all exchanged our expertise on sampling, handling and culture techniques. This were a couple of very productive sessions.

To round off an amazing week, on Saturday morning we visited the UNESCO World Heritage Site at Bryggen, where we learned about the history and traditions of Bergen. At sunset, we took the cable car up to Mount Ulriken and, after enjoying the incredible views, we held the award ceremony and the election of the new president of the Hydrozoan Society, who was unanimously elected: Dr. Lucas Leclère!

The social activities included a visit to Bryggen, an excursion to Fløyen, and the conference dinner in the top of Mount Ulrikken. The best student presentation awards were given and the new President of the Hydrozoan Society was elected. Exciting times ahead!

The third group picture we took in just a few days, this time with an incredible view of the city of Bergen as a background.

I would like to close this chronicle by thanking UMB’s Cnidaria and Ctenophora group: Aino Hosia, Luis Martell and Joan Soto, for their incredible work in coordinating the presentations, transfers and field work and for hosting such a rewarding event. I would also like to mention the great work done by all the students of the group, who helped organize the meals on the sampling days and other various activities. Thanks to all of them, the rest of us simply enjoyed the week.

It was definitely an experience worth repeating. I’m already looking forward to the next workshop in France!

-Marta Gil