Once again, it is time to celebrate our segmented friends from the sea – the Polychaetes, or bristle worms!

The tradition began in 2015 as a way to commemorate Kristian Fauchald, a key figure in the polychaetologist community for many years – as as a way for us to show off the cool critters that we work with!

We here at the Invertebrate collections have been celebrating in blog form each year, you can find the previous posts here:

2015: The 1st International Polychaete Day!

2016: Happy International Polychaete Day!

2017: Happy Polychaete Day!

For the 2015 celebration we were lucky enough to receive some stunning images from polychaete photographers extraordinaire Fredrik Pleijel and Arne Nygren (as well as some of mine), I think those deserve another round in the spotlight:

[slideshow_deploy id=’2648′]

As readers of this blog may be aware of, polychaetes are mainly marine, and live from the intertidal down to the abyssal zone. There’s more than 12 000 species of them world wide, and they can be active swimmers or live in burrows, be hunters, scavengers, carnivores or herbivores, filter feeders, or parasites. The group display a wide varity of body shapes, life modes and colours. Many are quite beautiful!

Phyllodoce citrina, Photo by Arne Nygren CC-BY-SA

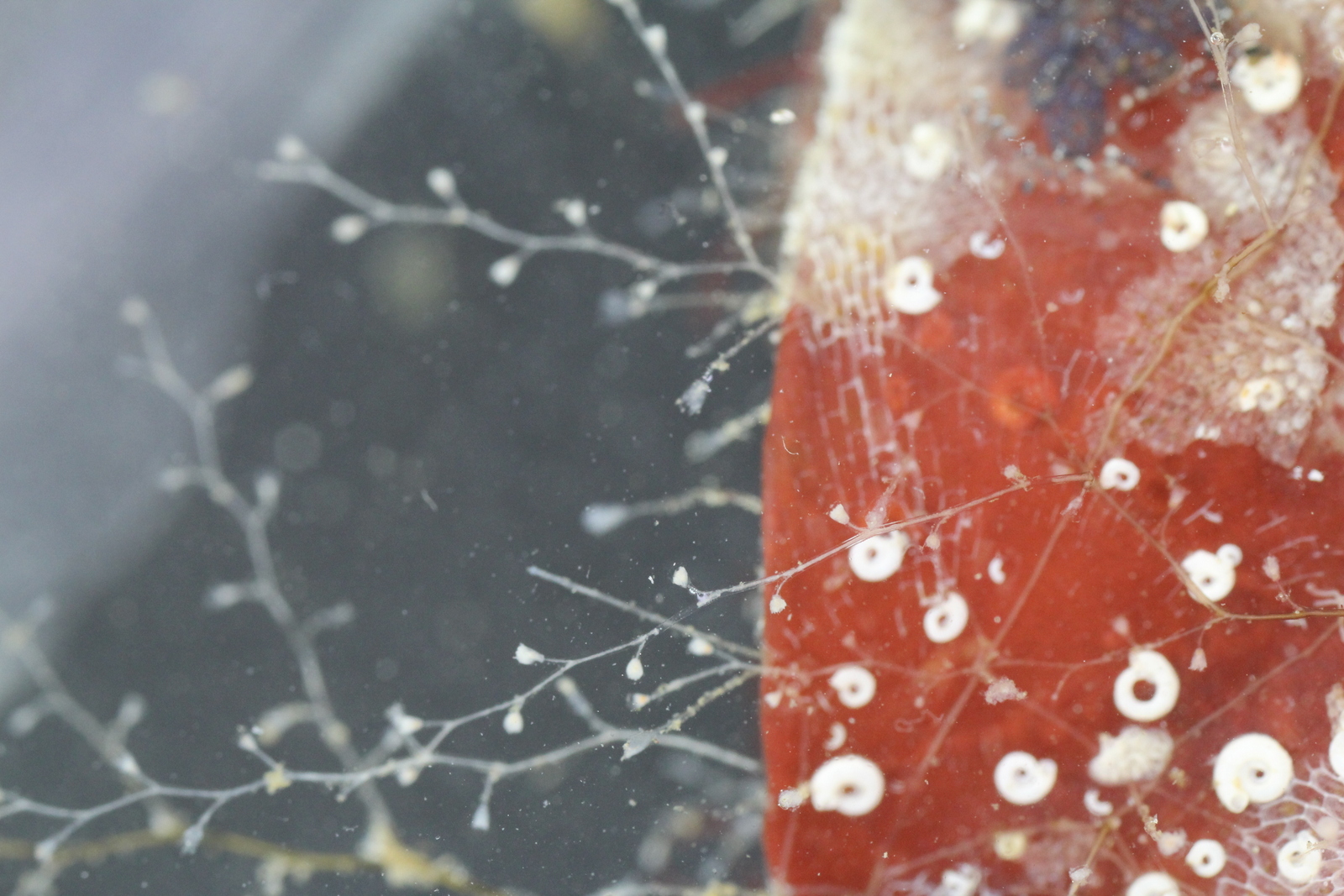

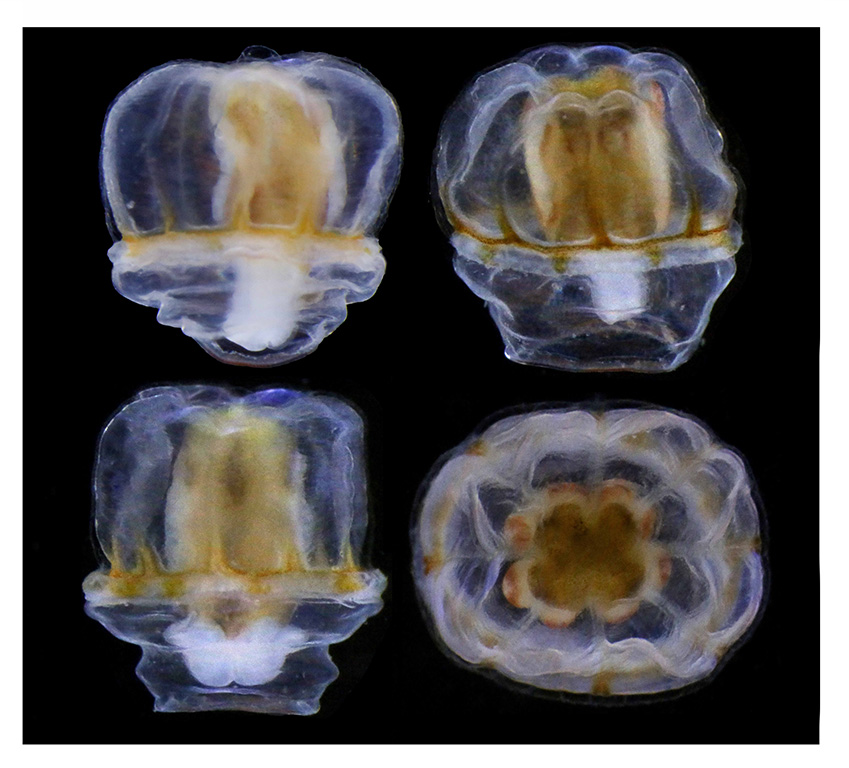

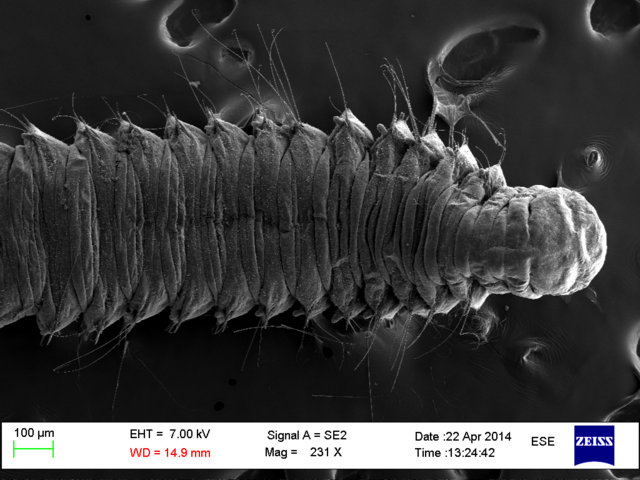

This year we would like to highlight some of the science that employees here have contributed to, and share some glimpses of what we work on. People sometimes wonder if we “ever find new species?” and the answer to that is an unequivocal “YES”. It really is not entirely uncommon to come across undescribed species (especially of the minute variety) – the challenge often lies more in finding the time to formally describe them. We have a couple of species in the pipeline at the moment, such as this Orbiniella sp. n. from the Bergen region that we hope to finish describing quite soon

New to science!

Who works with polychaetes? On the recent International Polychaete Conferences (blog posts from2013 and 2016, web page for the upcoming in 2019) there was around 150 attendees.

-

-

Group photo of the assembled polychaetologists in Sydney in 2013 (photo

© the IPC 2013 crew)

-

-

Polychaetologists assembled on the steps of the National Museum Cardiff (c) IPC2016

The “polychaetologists”, or polychaete researchers, are a collaborative bunch, and most of our work involves co-authors from other institutions, and often also from several countries. We share material, go on and receive research visits, arrange workshops and field work, and co-author. Pictured here are some of the recent new species that have been described by people from the invertebrate collections (with co-authors, of course!):

-

-

Neosabellides lizae from the intertidal From: Alvestad, T & Budaeva, N (2015)

-

-

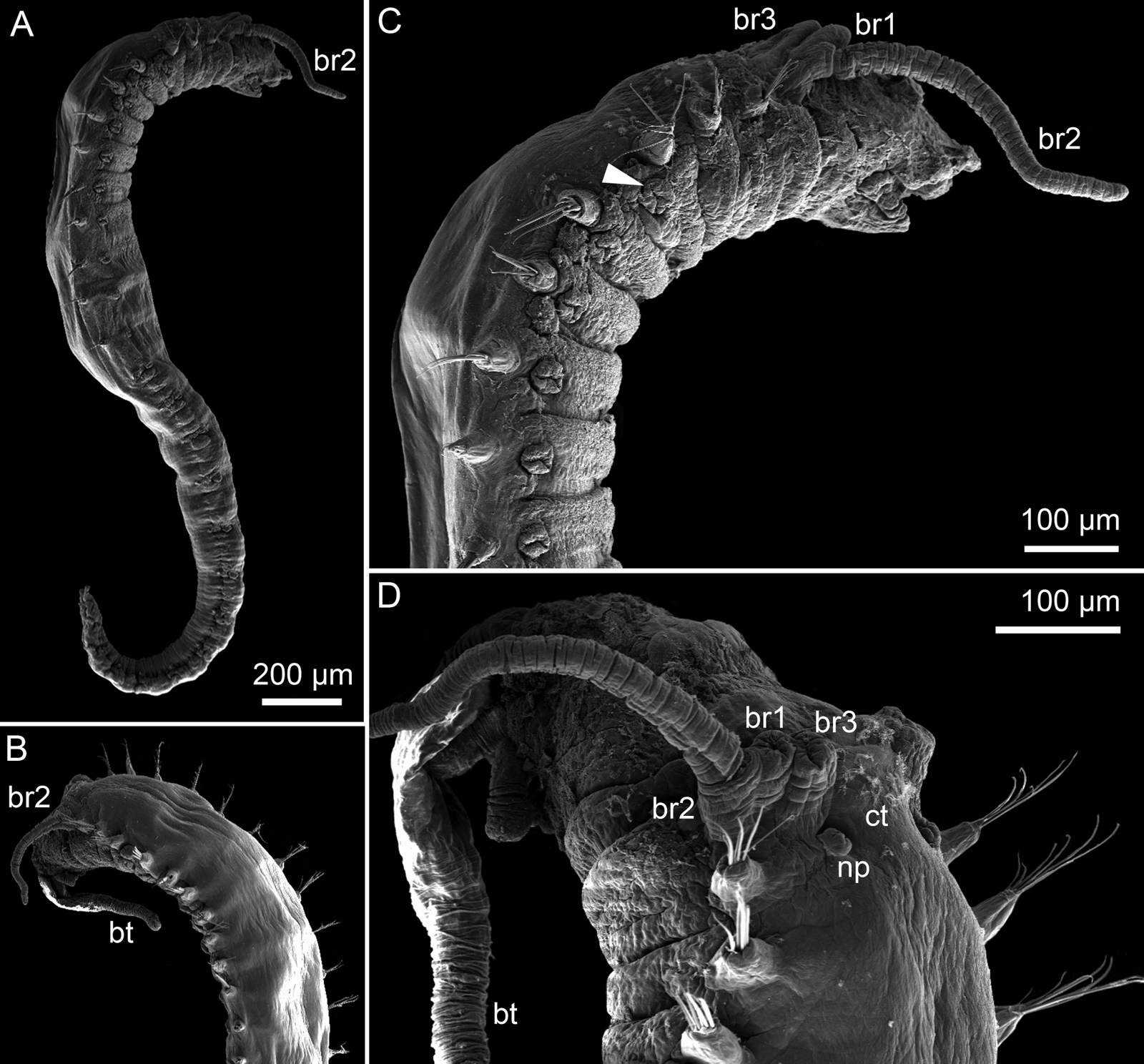

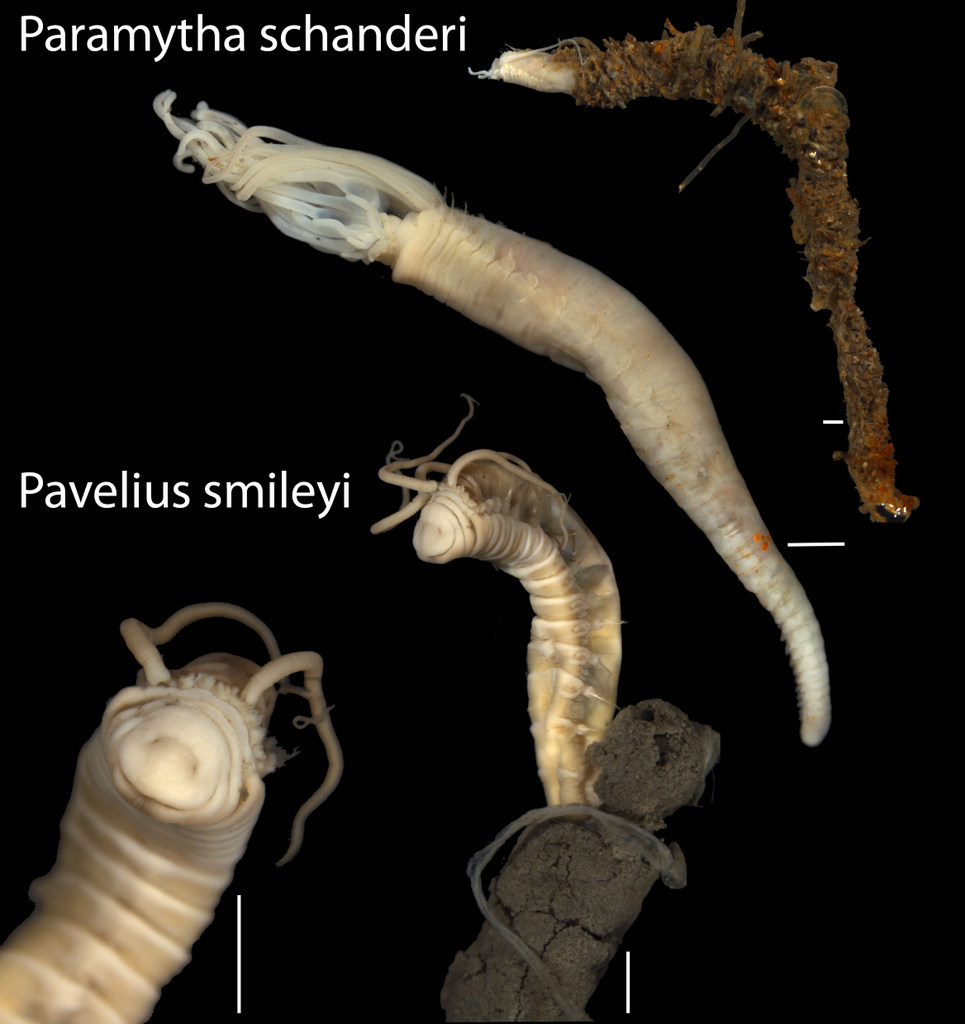

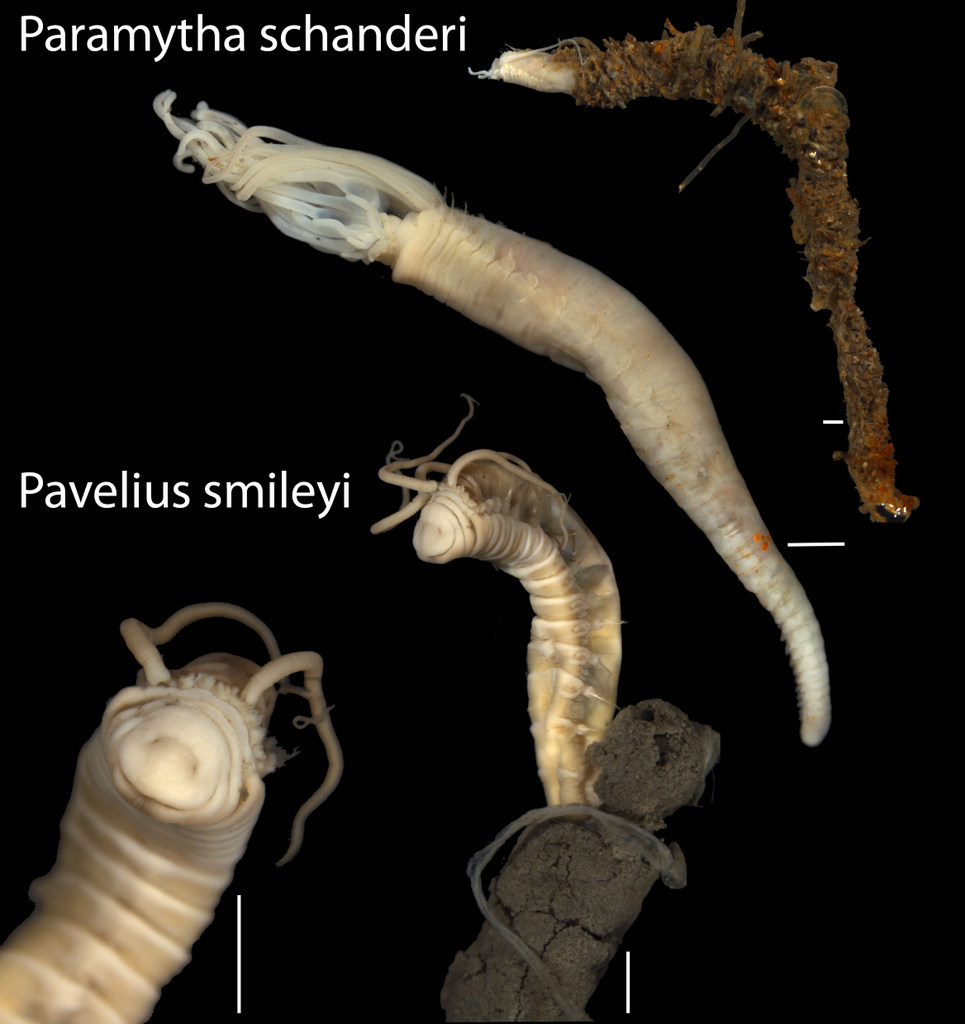

New species from the Arctic Loki’s Castle vent field: one named for our good friend Christoffer Schander, and the other for it’s happy contenance From: Kongsrud et al 2017

-

-

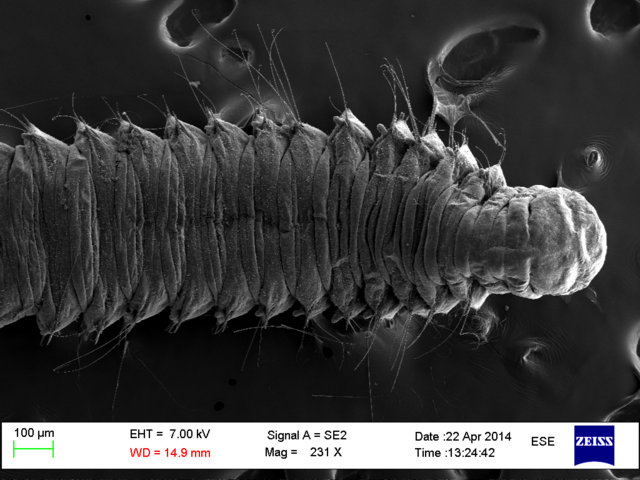

Scalibregma hanseni decribed from Norwegian waters. From: Bakken, T., Oug, E., Kongsrud, J.A. (2014)

-

-

Ampharete undecima. From: Alvestad, T., Kongsrud, J.A., Kongshavn, K. (2014)

To better our understanding of the diversity of the group, we use a combination of traditional morphology based identifications, and genetic methods.

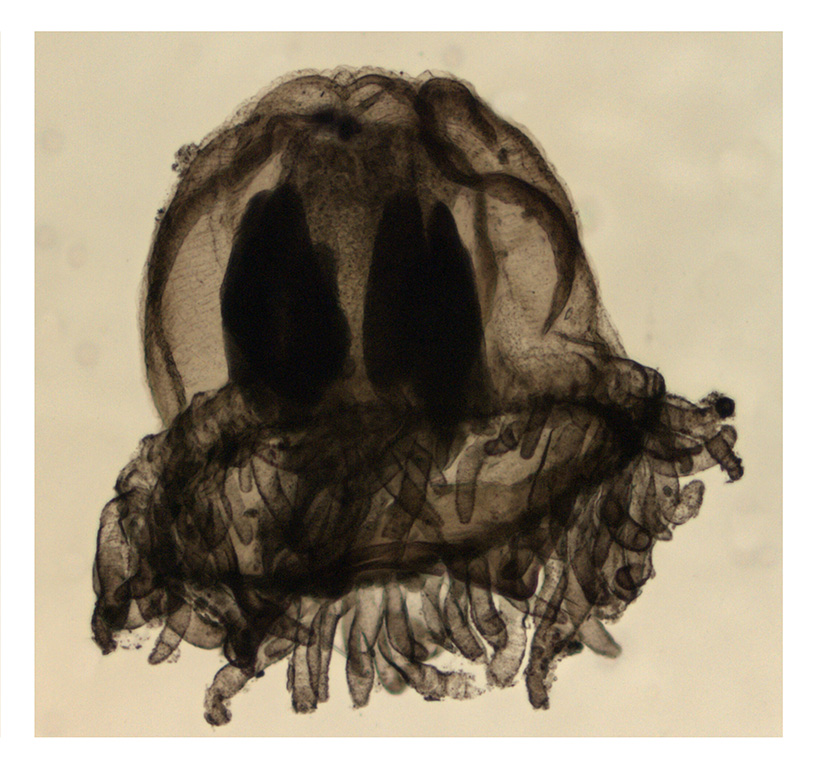

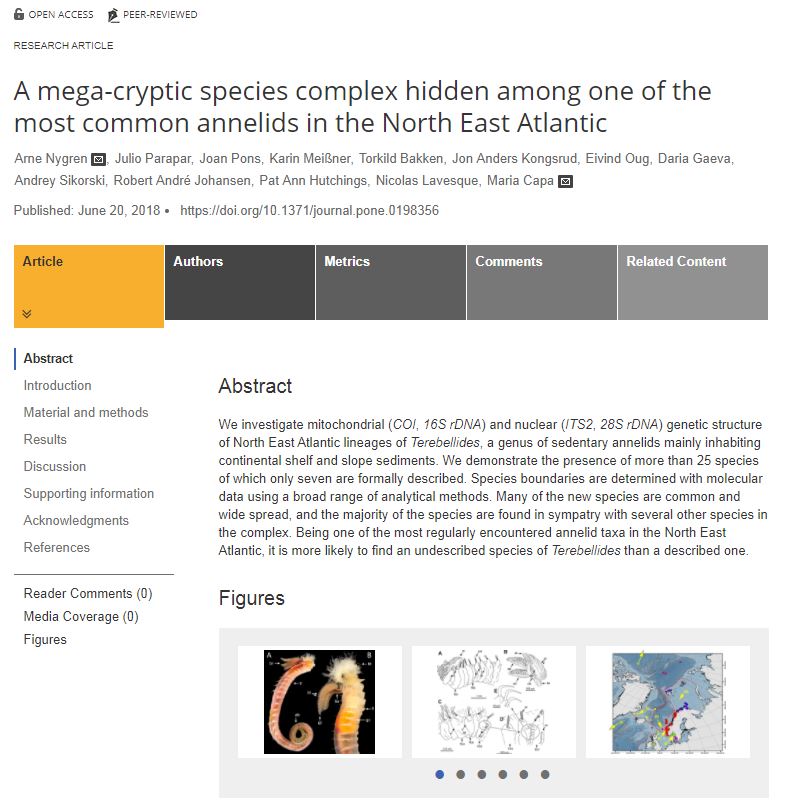

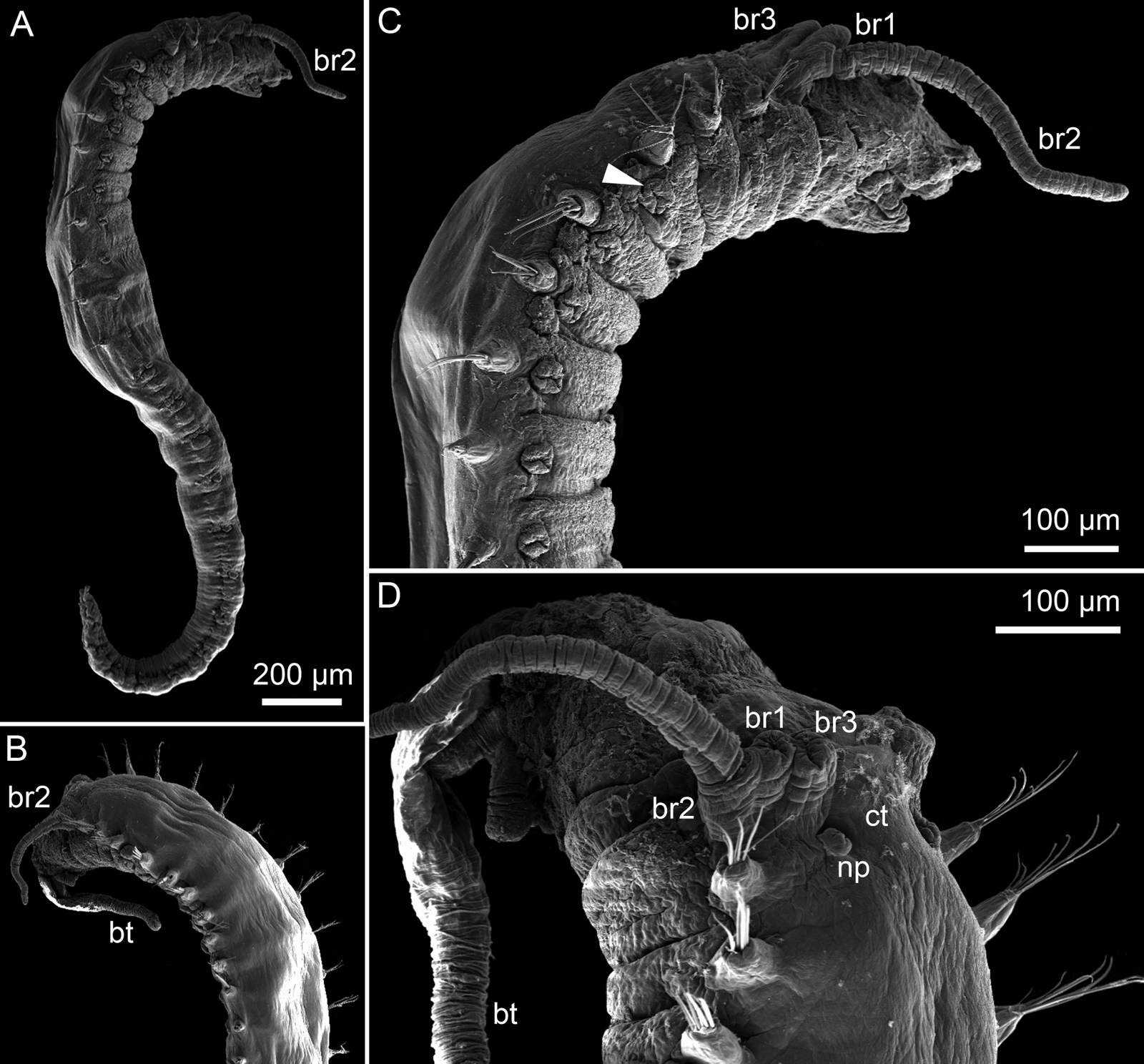

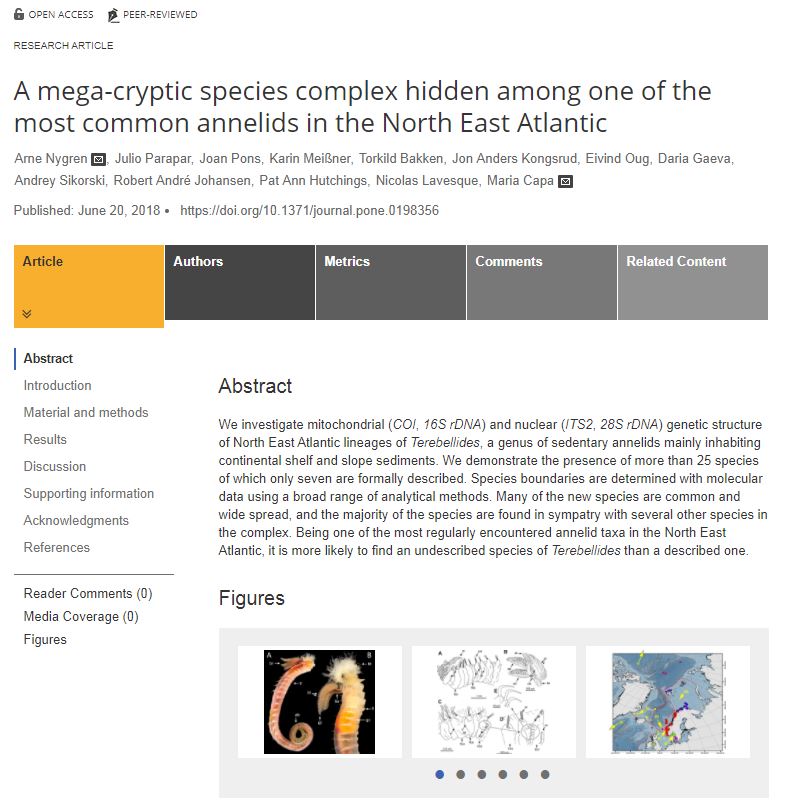

The recent paper by Arne Nygren et al. (2018) A mega-cryptic species complex hidden among one of the most common annelids in the North East Atlantic, published in PLOS ONE 13(6) e0198356. and available through open access here: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198356 is a striking example of how much higher the diversity might be. The paper examines the cryptic species diversity of the genus Terebellides in the North-East Atlantic, and reveals a stunning genetic diversity:

“Many of the new species are common and wide spread, and the majority of the species are found in sympatry with several other species in the complex. Being one of the most regularly encountered annelid taxa in the North East Atlantic, it is more likely to find an undescribed species of Terebellides than a described one“

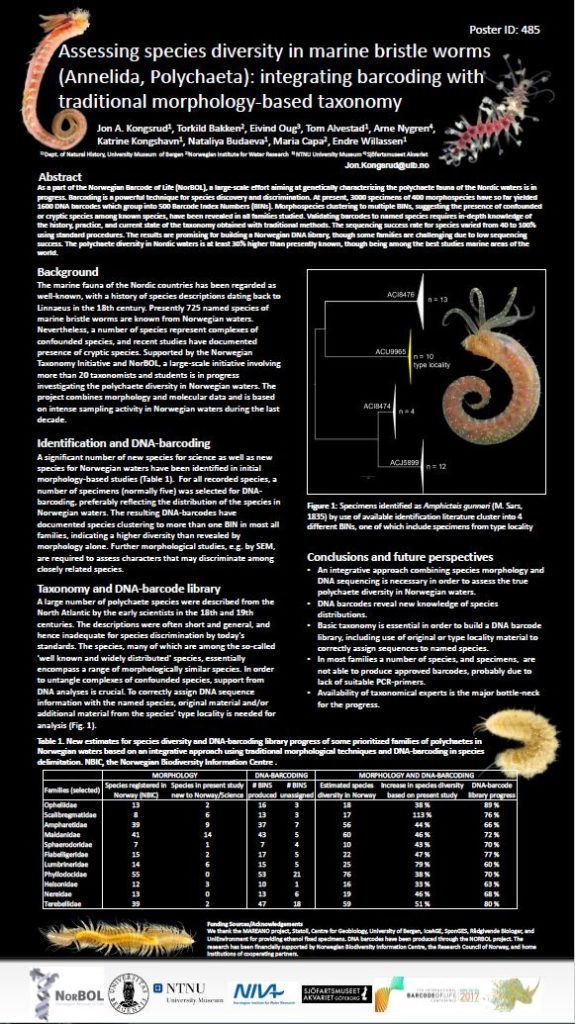

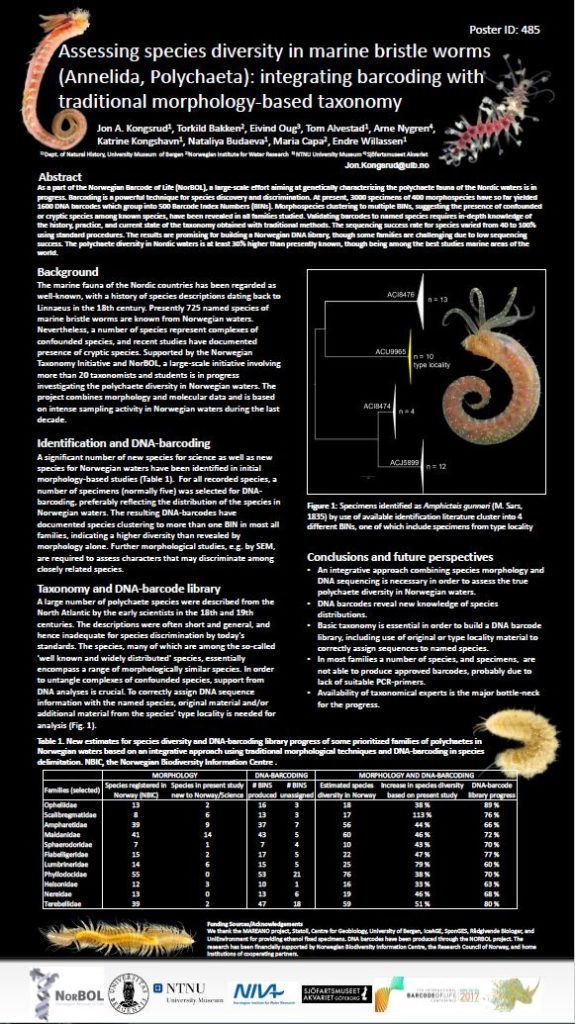

This fits well with what we have observed though our work on polychaete diversity in the Nordic seas through several Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative Projects (“Artsprosjekt”), and studies of the museum material. We presented a summary of our findings for some polychaete families at the IBOL conference in South Africa. We find that there is a clear need for thorough vetting of reference databases of genetic barcodes so that the barcodes can be validated to named species – and to do that, we first need to figure out who is who! This requires in-depth knowledge of the history, practice, and current state of the taxonomy obtained with traditional methods. We find that the polychaete diversity in Nordic waters is at least 30% higher than presently known, even though this is among the best studied marine areas of the world.

All the posters can be found on the conference web site, ours is #825.

In other words, there is much left to explore!

To continue the Polychaete Day celebrations, head on over to Twitter and #PolychaeteDay!

Polychaete papers involving authors from the Invertebrate Collections:

Alvestad, T & Budaeva, N (2015) Neosabellides lizae, a new species of Ampharetidae (Annelida) from Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Zootaxa 4019 (1): 061–069

Alvestad, T.,Kongsrud, J.A., Kongshavn, K. (2014) Ampharete undecima, a new deep-sea ampharetid (Annelida, Polychaeta) from the Norwegian Sea. Memoirs of Museum Victoria 2014; Volume 71. pp. 11-19

Arias A., Paxton H., Budaeva N. 2016. Redescription and biology of Diopatra neapolitana (Annelida: Onuphidae), a protandric hermaphrodite with external spermaducal papillae. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 175: 1–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2016.03.002

Budaeva, N. (2014) Nothria nikitai, a new species of bristle worms (Annelida, Onuphidae) from the Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean. Marine Biodiversity 2014, DOI:10.1007/s12526-014-0244-1

Budaeva, N., Jirkov, I., Savilova, T., Paterson, G. (2014) Deep-sea fauna of European seas: An annotated species check-list of benthic invertebrates living deeper than 2000 m in the seas bordering Europe. Polychaeta. Invertebrate Zoology 2014 ;Volum 11.(1) s. 217-230

Budaeva, N., Pyataeva, S., Meissner, K. (2014) Development of the deep-sea viviparous quill worm Leptoecia vivipara (Hyalinoeciinae, Onuphidae, Annelida). Invertebrate biology. 2014; Volume 133.(3) s. 242-260

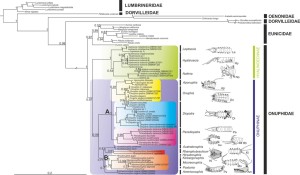

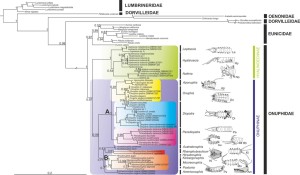

Phylogenetic tree of a bristle worm family Onuphidae (Budaeva et al., 2016)

Budaeva N., Schepetov D.,Zanol J., Neretina T., Willassen E. (2016) When molecules support morphology: Phylogenetic reconstruction of the family Onuphidae (Eunicida, Annelida) based on 16S rDNA and 18S rDNA. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 94(B): 791–801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2015.10.011

Eilertsen, M., Georgieva, M., Kongsrud, J.A, Linse, K., Wiklund, H.G., Glover, A., Rapp, H.T. (2018). Genetic connectivity from the Arctic to the Antarctic: Sclerolinum contortum and Nicomache lokii (Annelida) are both widespread in reducing environments. Scientific Reports 8:4810 | DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-23076-0

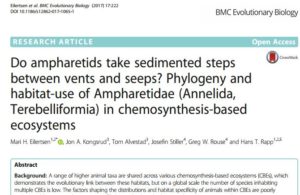

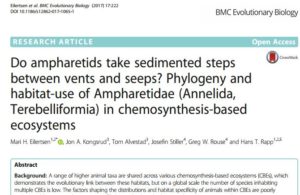

Eilertsen, M., Kongsrud, J.A, Alvestad, T., Stiller, J., Rouse, G., & Rapp, H.T (2017). Do ampharetids take sedimented steps between vents and seeps? Phylogeny and habitat-use of Ampharetidae (Annelida, Terebelliformia) in chemosynthesis-based ecosystems. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17. 222. Doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-1065-1.

Kongsrud J.A., Eilertsen M.H., Alvestad T., Kongshavn K., Rapp HT. (2017) New species of Ampharetidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from the Arctic Loki Castle vent field. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 137: 232-245. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2016.08.015

Kongsrud J.A., Eilertsen M.H., Alvestad T., Kongshavn K., Rapp HT. (2017) New species of Ampharetidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from the Arctic Loki Castle vent field. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 137: 232-245. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2016.08.015

Kongsrud, J.A., Budaeva, N., Barnich, R., Oug, E., Bakken, T. (2013) Benthic polychaetes from the northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge between the Azores and the Reykjanes Ridge, Marine Biology Research, 9:5-6, 516-546, DOI: 10.1080/17451000.2012.749997

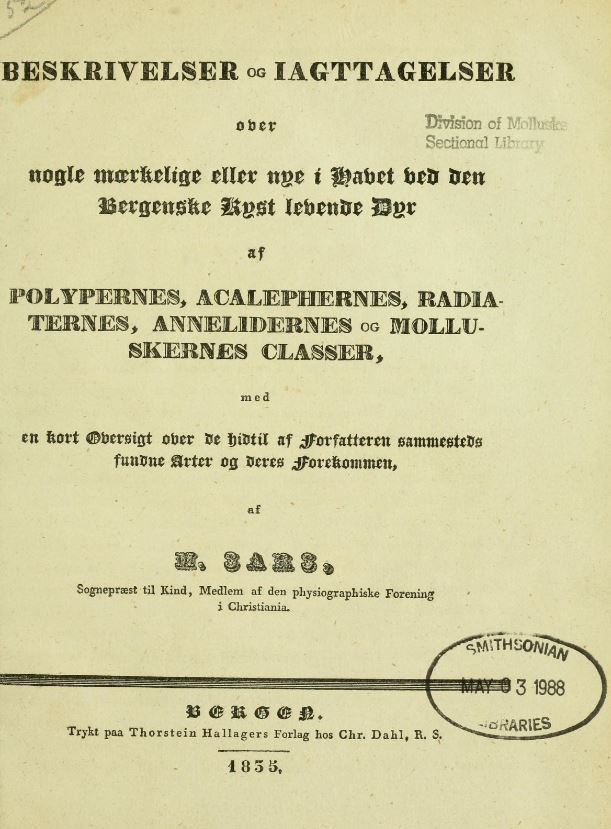

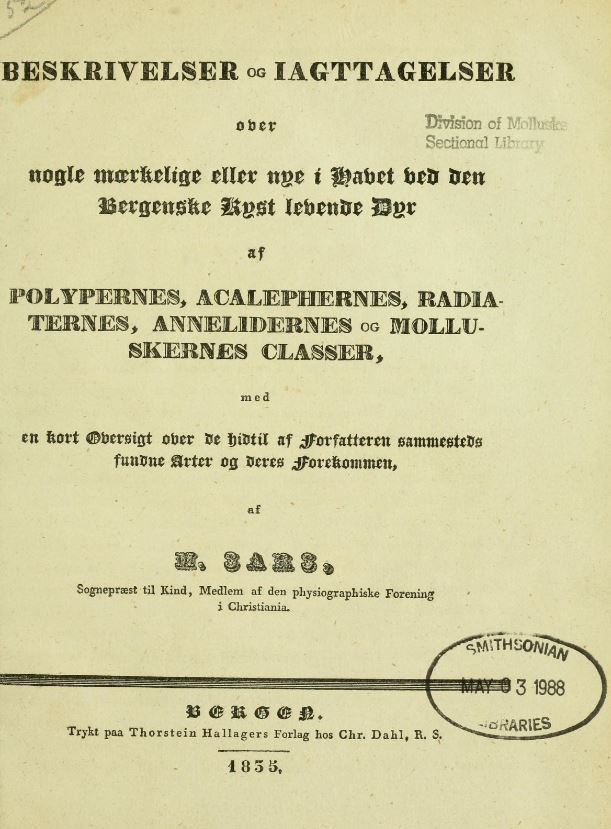

Oug, E., Bakken, T. & Kongsrud, J.A. (2014) Original specimens and type localities of early described polychaete species (Annelida) from Norway, with particular attention to species described by O.F. Müller and M. Sars. Memoirs of Museum Victoria 71, 217-236 http://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.2014.71.17

-

-

From type locality..

-

-

…to type descriptions…

-

-

…to fresh specimens, here Amphicteis gunneri, collected at type locality. Photo: K.Kongshavn

Oug, E., Bakken, T., Kongsrud, J.A., Alvestad, T. (2016) Polychaetous annelids in the deep Nordic Seas: Strong bathymetric gradients, low diversity and underdeveloped taxonomy. Deep-sea research. Part II, Topical studies in oceanography. 137: 102-112. Publisert 2016-07-06. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2016.06.016

Parapar, J., Kongsrud, J.A., Kongshavn, K., Alvestad, T., Aneiros, F., Moreira, J. (2017). A new species of Ampharete (Annelida: Ampharetidae) from the NW Iberian Peninsula, with a synoptic table comparing NE Atlantic species of the genus. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlx077,https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx077

Queiros JP, Ravara A, Eilertsen MH, Kongsrud JA, Hilário A. (2017). Paramytha ossicola sp. nov. (Polychaeta, Ampharetidae) from mammal bones: reproductive biology and population structure. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 137: 349-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2016.08.017

Vedenin A., Budaeva N., Mokievsky V., Pantke C., Soltwedel T., Gebruk A. (2016) Spatial distribution patterns in macrobenthos along a latitudinal transect at the deep-sea observatory HAUSGARTEN. Deep-Sea Research Part I 114: 90–98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2016.04.015

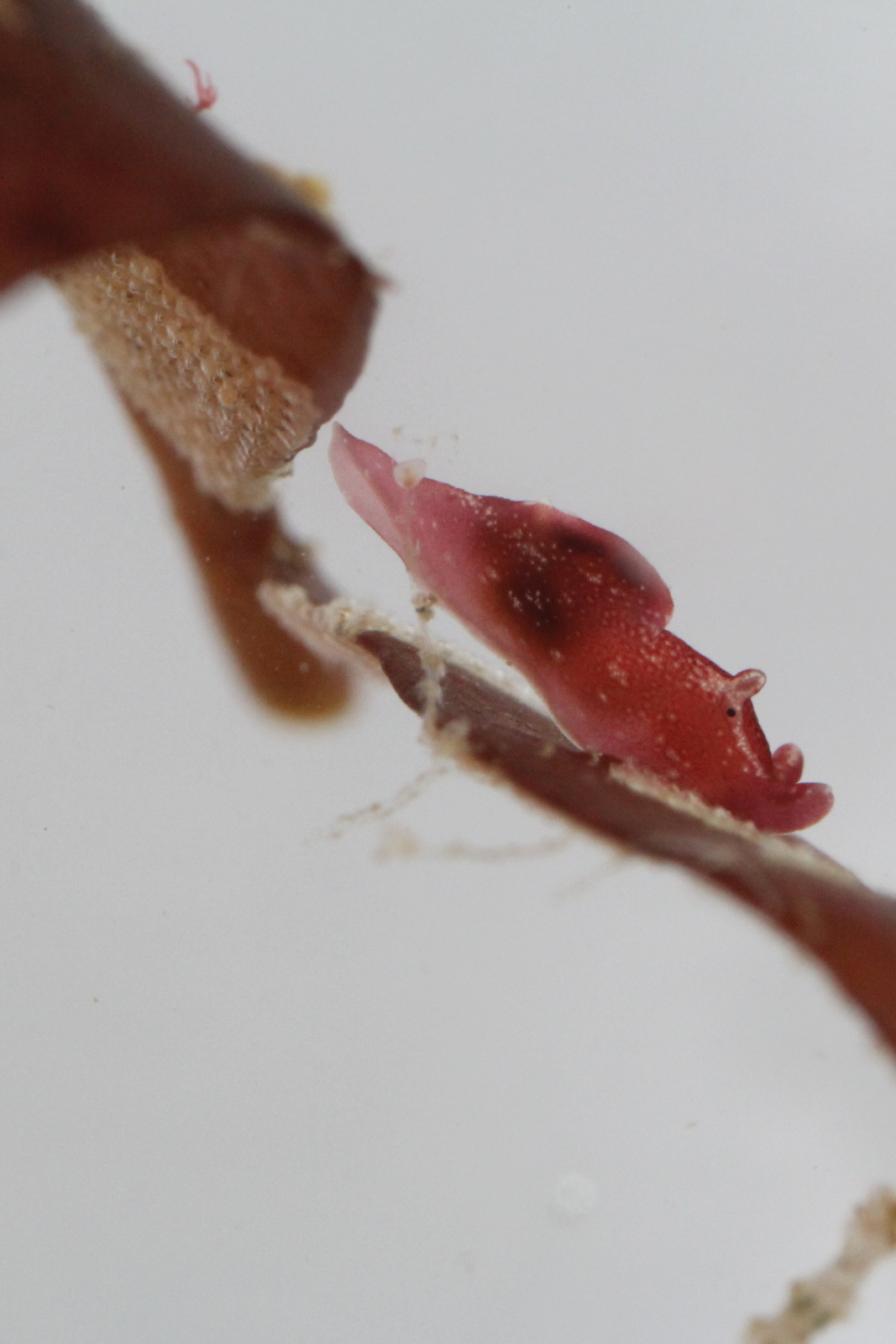

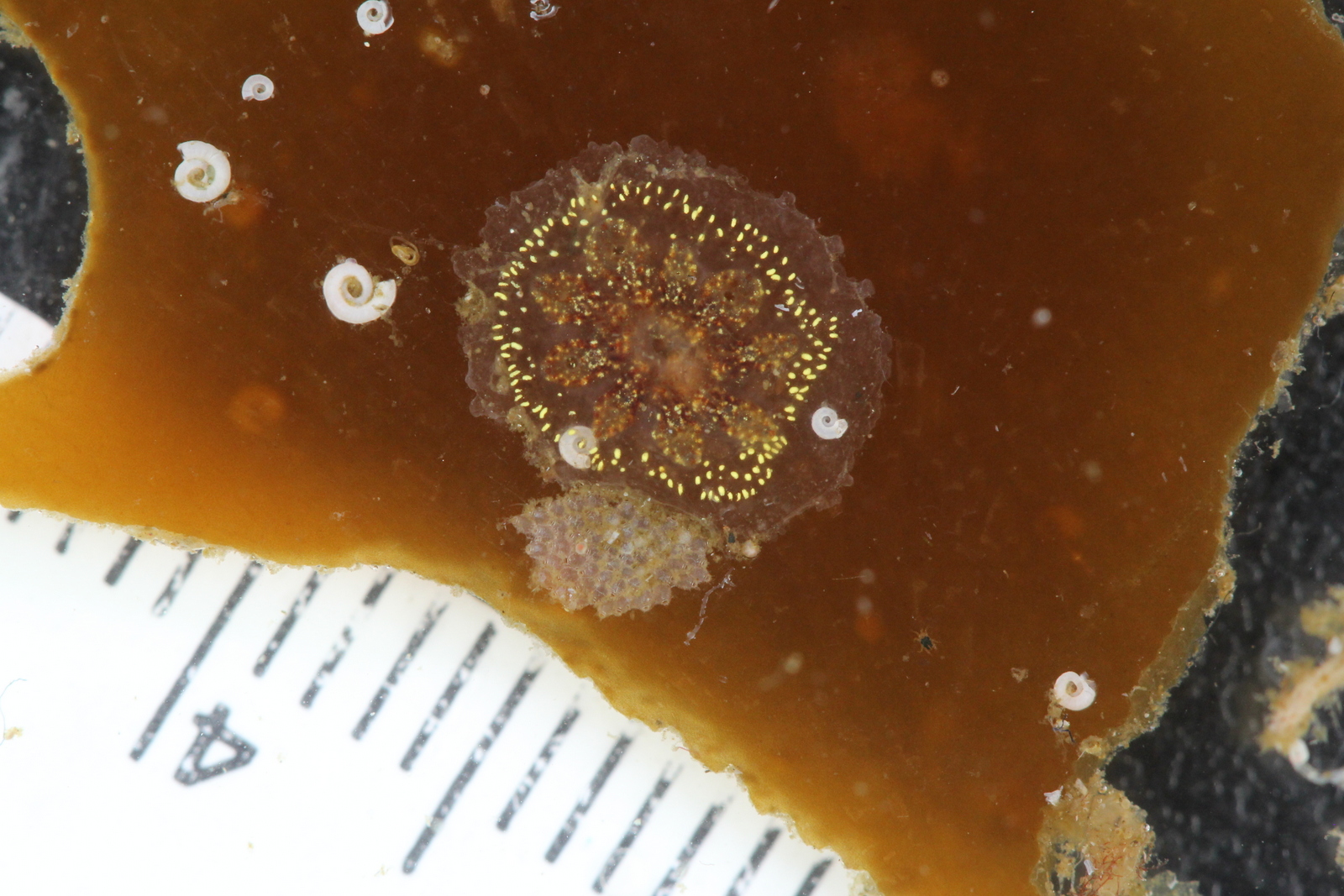

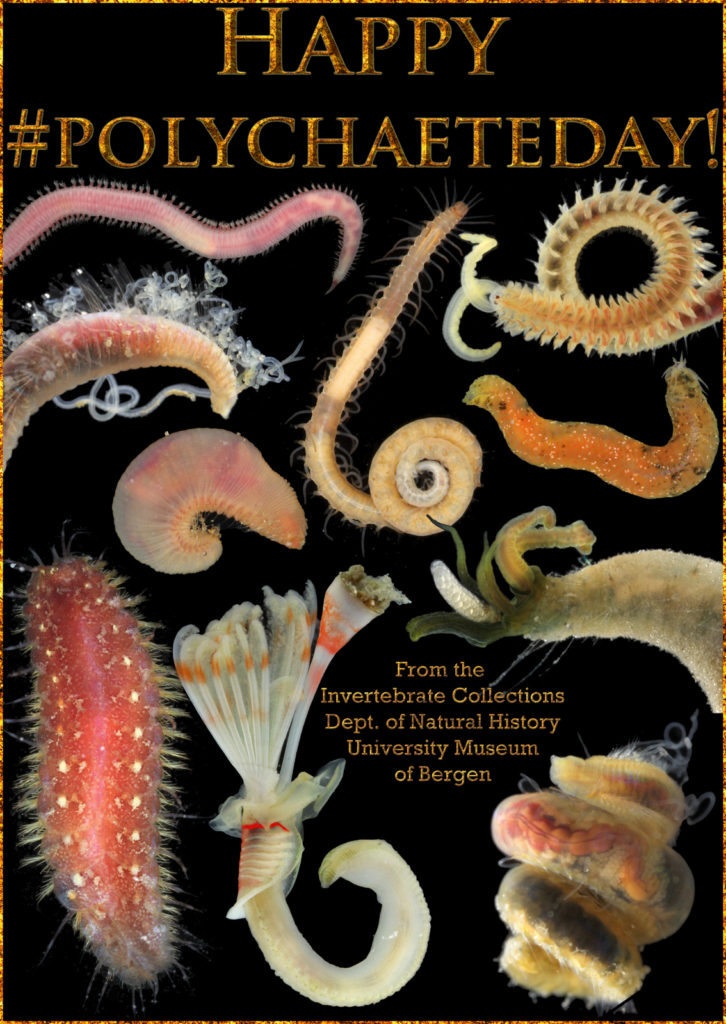

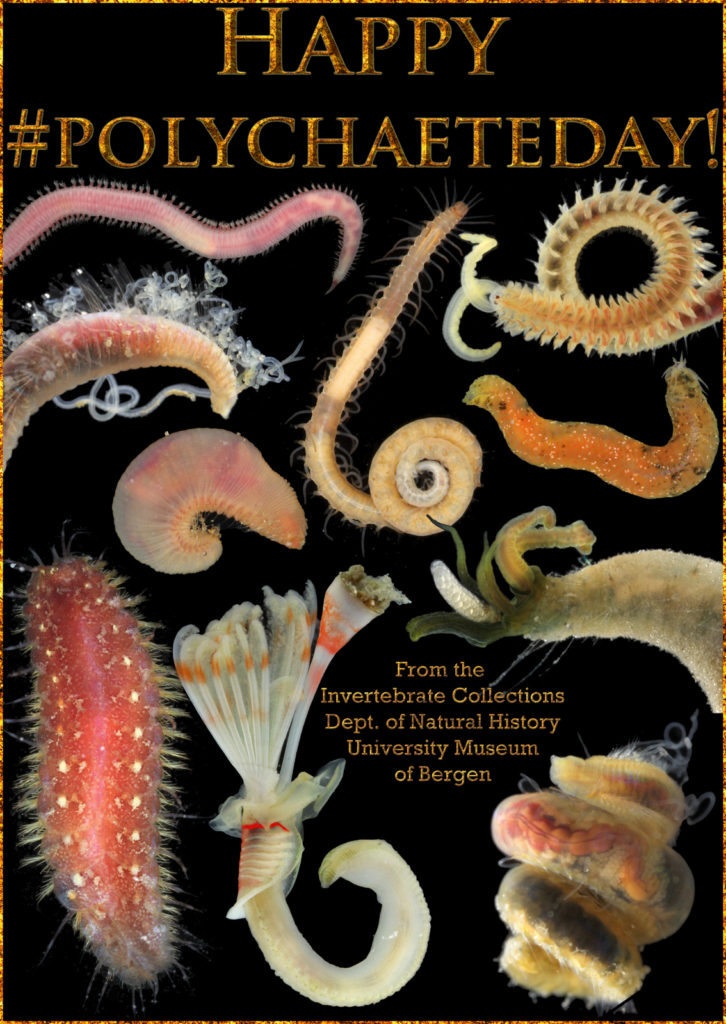

Some of the wonderful worms that were collected during #AnnelidaCourse2017. From top left: Glyceridae, Syllidae, Spionidae, Cirratulidae, Phyllodocidae, Scalibregmatidae, Flabelligeridae, Polynoidae, Serpulidae and Cirratulidae. Photos: K.Kongshavn

Some of the wonderful worms that were collected during #AnnelidaCourse2017. From top left: Glyceridae, Syllidae, Spionidae, Cirratulidae, Phyllodocidae, Scalibregmatidae, Flabelligeridae, Polynoidae, Serpulidae and Cirratulidae. Photos: K.Kongshavn

-Katrine