Endre, Katrine, Nataliya and Tom have recently been on a journey far removed from the ocean – although the location did hold a lot of fresh water…!

It really does look and feel a lot like an ocean…

We have – together with Torbjørn Ekrem from the NTNU University Museum – been teaching DNA barcoding at the Russian-Norwegian course “Data mobilization skills: training on mobilizing biodiversity data using GBIF and BOLD tools”, which was held in Naratey on the western shore of Lake Baikal September 14-20, 2018!

-

-

It was a long journey from Bergen..

-

-

..to Irkutsk, and then by bus..

-

-

..to Naratey (Наратэй)..

-

-

..close to Olkhon Island in Lake Baikal

The course consisted of two modules focusing on GBIF and BOLD tools. The GBIF part was taught by Dag Endresen from UiO, Laura Russell and Dmitry Schigel from the GBIF Secretariat.

The course consisted of two modules focusing on GBIF and BOLD tools. The GBIF part was taught by Dag Endresen from UiO, Laura Russell and Dmitry Schigel from the GBIF Secretariat.

It included both online preparatory work for the students and (mainly) onsite components. The online portion consisted of tasks that the students completed on GBIF’s eLearning portal.

The onsite work was comprised of 20 different sessions of lectures and practical exercises, the latter with a significant component of group work.

16 students from Norwegian and Russian intuitions participated, and did a wonderful job of assimilating a lot of information in a short amount of time, and turning it into practical skills.

-

-

Solving barcoding tasks. Photo: N. Budaeva

-

-

Students at work. Photo: N. Budaeva

-

-

Group work. Photo: K. Kongshavn

-

-

Deep concentration as MEGA is explored (note the local fauna that sneaked in!) Photo: N. Ivanova

-

-

Tom is ready to assist

-

-

Happy students – we like it! Photo: N. Budaeva

The two main platforms we used were GBIF and BOLD – two large depositories for different kinds of biodiversity data. The GBIF-part of the course focused on the technical aspects of data mobilization, such as data capture, and management and online publishing of biodiversity data in order to increase the amount, richness and quality of data published through the GBIF network.

Team GBIF getting set up Photo: N. Ivanova

BOLD; Barcode of Life Data Systems

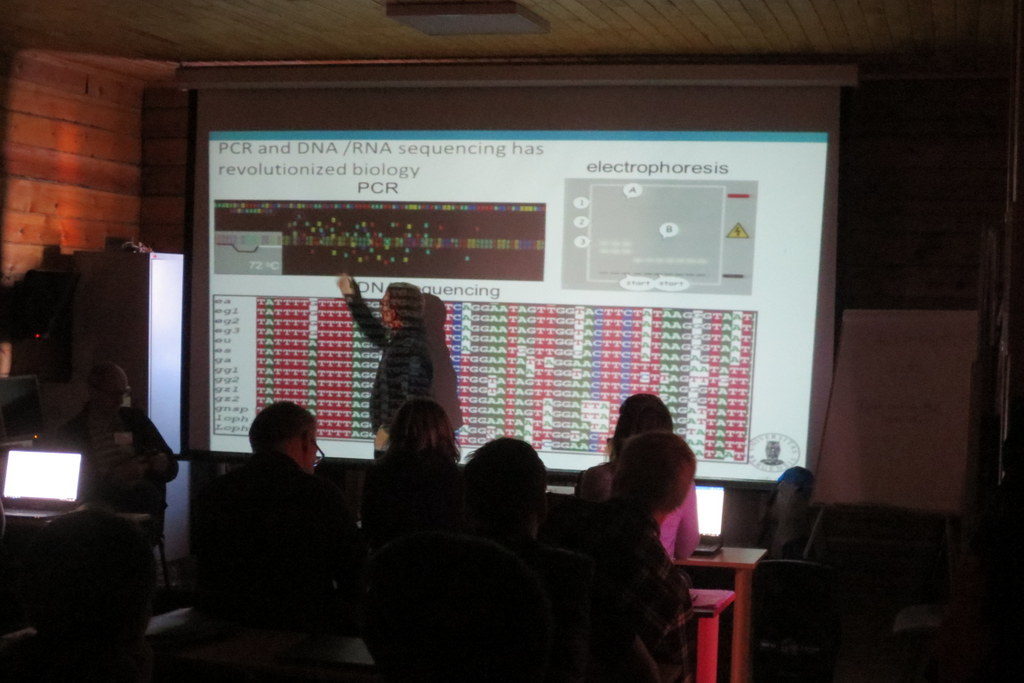

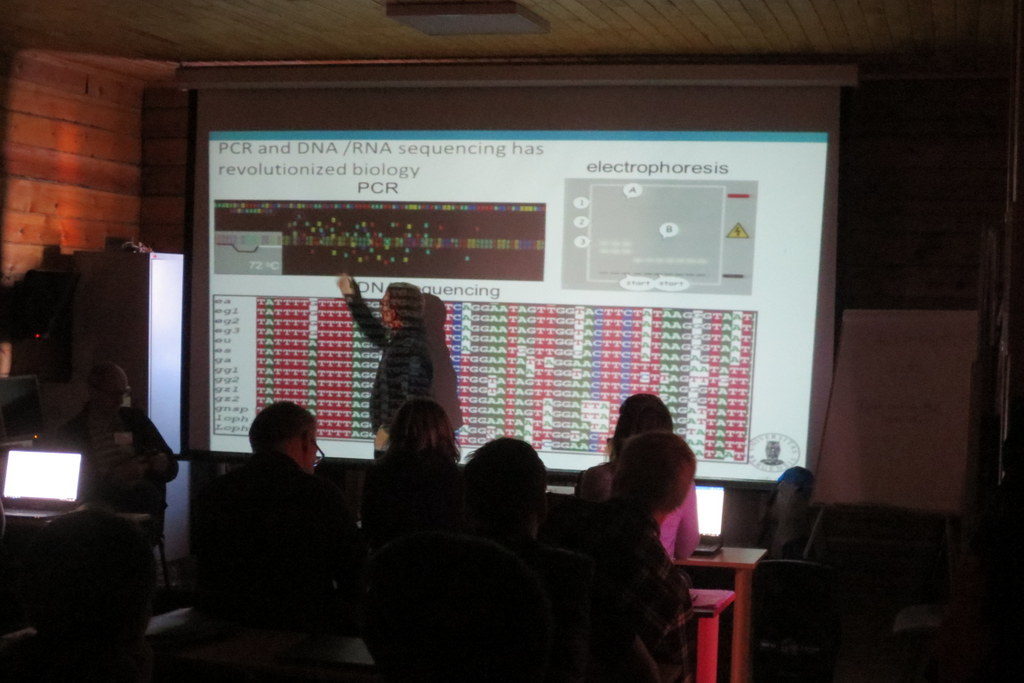

The barcoding part was aimed at both users and providers of barcoding data, and began with an introduction to the barcoding concept, and a case study of integrating data from BOLD and GBIF. This was followed by a session on the use of BOLD: creating projects and datasets, and the uploading of data, images, sequences and trace files. The students got to try all of this for themselves, and we were impressed by how well they worked together to find solutions and teach each other valuable tricks to solve the challenges.

-

-

Endre is becoming one with the sequences..

-

-

Torbjørn presenting the biodiversity challenge

Following the lessons on how to get sequence data into the database, we covered basics of sequence analysis, and gave an introduction to the free software MEGA X which can be used for sequence alignment, translation and phylogeny.

Working in MEGA Photo: k. Kongshavn

This was again followed by a practical session in MEGA on a given data set. We also had a session presenting the analytical tools in BOLD, with a practical session exploring a dataset from NTNU. Our lessons were very well received by the students, with an average score of 4.8 out of a possible 5 on the evaluations – nice feedback for the teachers!

Students and teachers gathered in the Siberian sun

Photo: Dmitry Schigel, CC-BY-SA

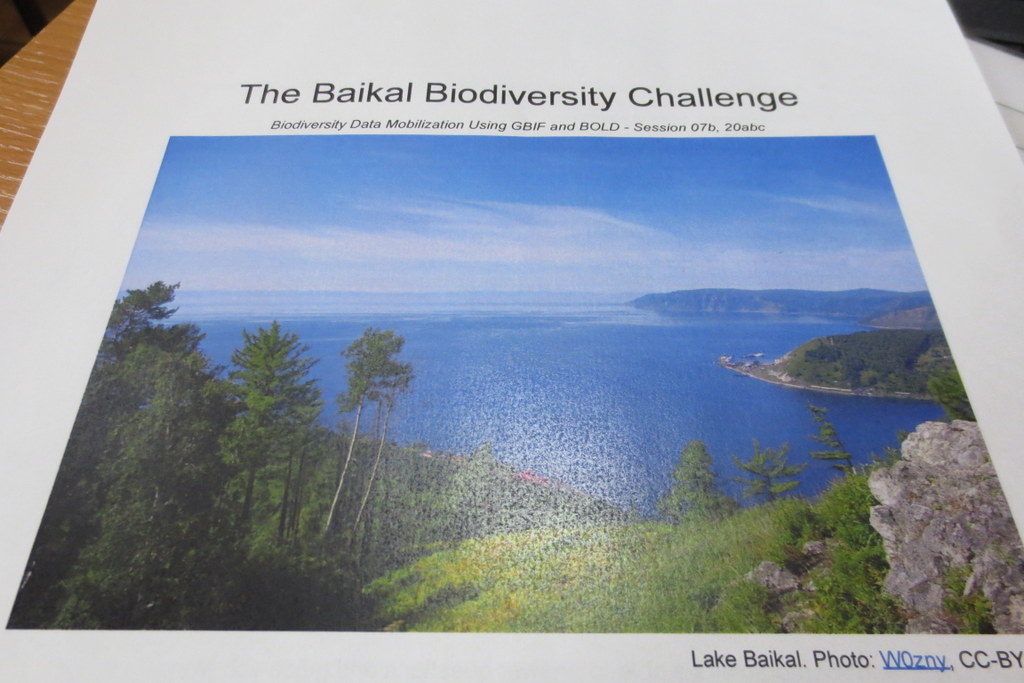

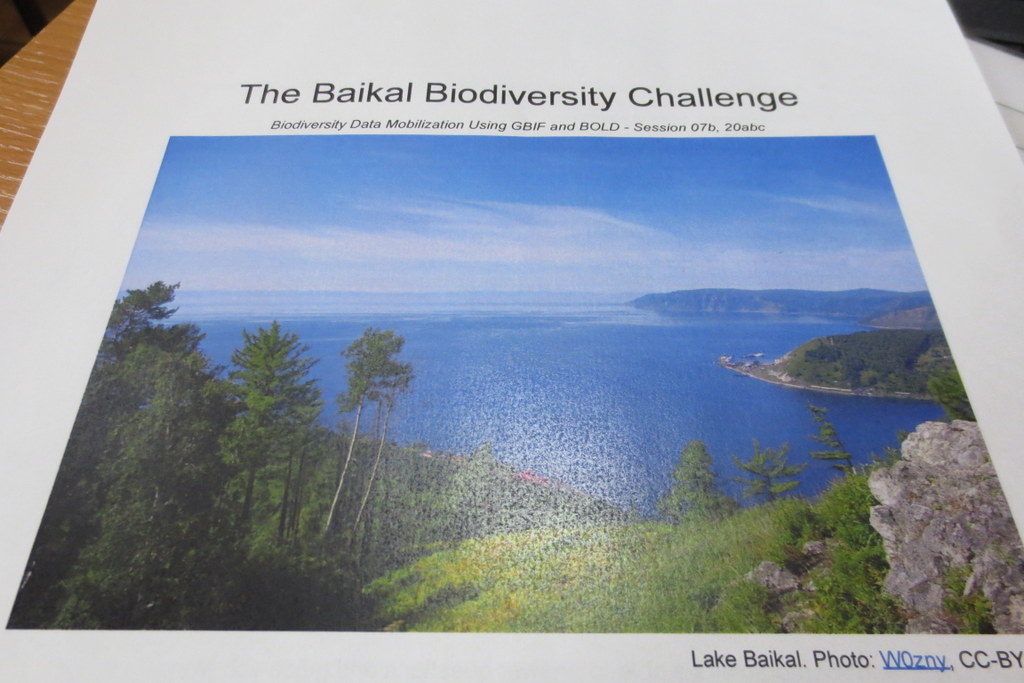

The final task for the students was to present their presentations for “The Baikal Biodiversity Challenge”, which they were presented with on the first day of the course.

The Baikal Biodiversity Challenge

The challenge was to develop a biodiversity inventory project to map and analyze the diversity of a selected animal group. To do so they would need to use available information in BOLD, GBIF and other sources to examine what was known and identify information that was missing, and come up with suggestions on how it could be solved. It was not the easiest of tasks, however all four groups gave excellent presentations.

Group selfie wearing the NorBOL buff scarves – #mydnabarcode! Photo by Laura Russell, CC-BY-SA

The course was arranged as collaboration between the University of Bergen, the Siberian Institute of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Russian Academy of Sciences (SIPPB SB RAS), the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) Secretariat. NorBOL (Norwegian Barcode of Life) supplied the teachers for the barcoding part of the programme, namely Endre, Torbjørn, Katrine and Tom. Funding came from the Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (previously SIU, now DIKU), GBIF and the Research School in Biosystematics (ForBio).

For those who might not know, ForBio is a teaching and research initiative coordinated by the Natural History Museum in Oslo, the University Museum of Bergen, the Tromsø University Museum and the NTNU University Museum. It is funded by the Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative and the Research Council of Norway. The Research School offers a wide variety of both practical and theoretical courses in biosystematics, and provides a platform for facilitating teaching and research collaboration between Nordic research institutes. The course portfolio is likely to have something of interest to offer if you work with anything related to biosystematics –and is open (and often free) to you if you are student, researcher or staff at universities, institutes and consulting companies.

For those who might not know, ForBio is a teaching and research initiative coordinated by the Natural History Museum in Oslo, the University Museum of Bergen, the Tromsø University Museum and the NTNU University Museum. It is funded by the Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative and the Research Council of Norway. The Research School offers a wide variety of both practical and theoretical courses in biosystematics, and provides a platform for facilitating teaching and research collaboration between Nordic research institutes. The course portfolio is likely to have something of interest to offer if you work with anything related to biosystematics –and is open (and often free) to you if you are student, researcher or staff at universities, institutes and consulting companies.

Most of the ForBio courses are arranged in Norway or other Nordic countries – but this course was the second of a total six that are arranged as part of the SIU-funded MEDUSA*-project (Multidisciplinary EDUcation and reSearch in mArine biology in Norway and Russia), which is coordinated by Nataliya. The six courses are

- ForBio and DLN course: Comparative Morphology Methods (Trondheim, Norway 2018)

- Data mobilization skills: training on mobilizing biodiversity data using GBIF and BOLD tools (Siberia, Russia 2018)

- Zooplankton communities – taxonomy and methods (Espegrend Marine Biological Station, UiB, Norway, tentatively May 2019)

- Systematics, Morphology and Evolution of Marine Mollusks (Vostok Marine Research Station, Institute of Marine Biology, Vladivostok, Russia, September 2019)

- Systematics, Morphology and Evolution of Marine Annelids (Espegrend Marine Biological Station, UiB, Norway, tentatively June 2020)

- Diversity and Evolution of Meiobenthos (White Sea Biological Station, Moscow State University, Russia, September 2020)

We enjoyed the opportunity to visit such a remote locality, and to get to know the students and teachers – thank you all for making this such a wonderful experience!

Thanks also to the BOLD support team for excellent help before and during the course!

A few snapshots from the area – it was stunning! Photos by K. Kongshavn

A beautiful view from Olkhon Island (after the course), photo by K.Kongshavn

ps: we also tweeted using #ForBio_GBIF during the course

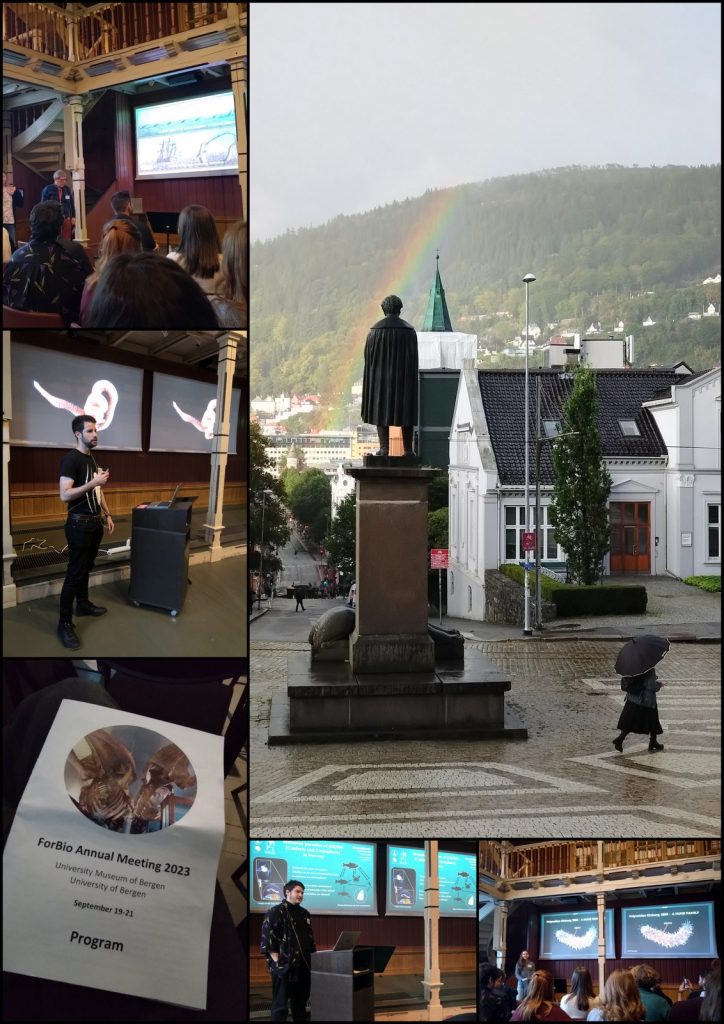

Sixty participants from Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Czech Republic, Poland, Germany and Peru presented their research results in various fields of biosystematics.

Sixty participants from Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Czech Republic, Poland, Germany and Peru presented their research results in various fields of biosystematics.

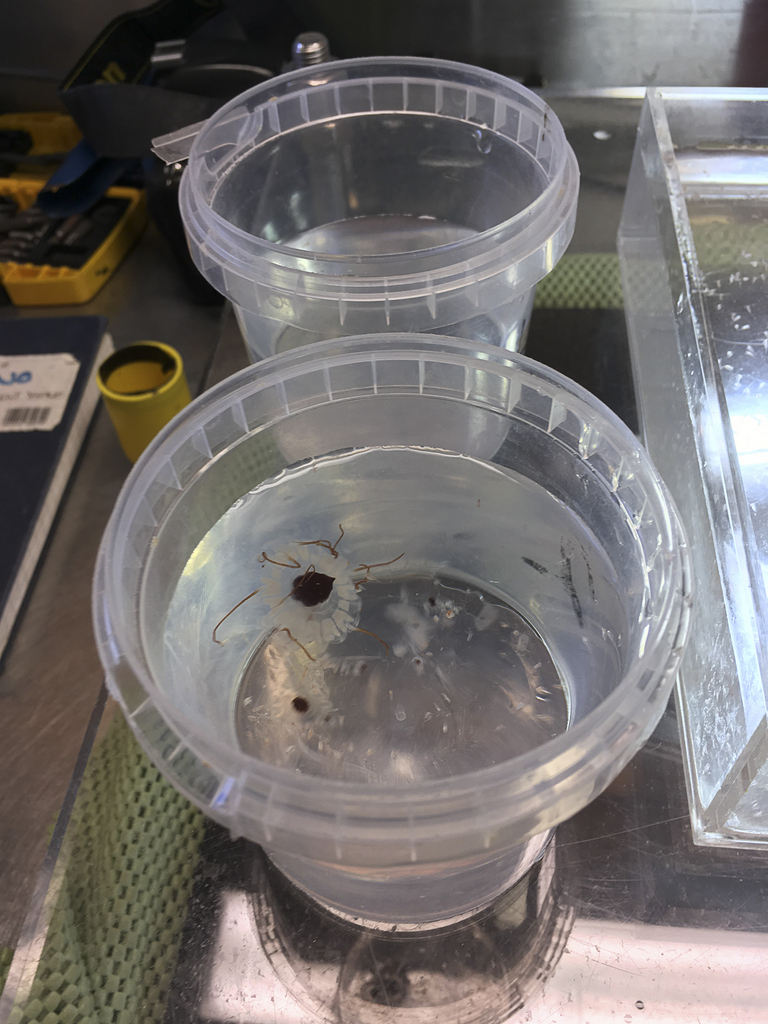

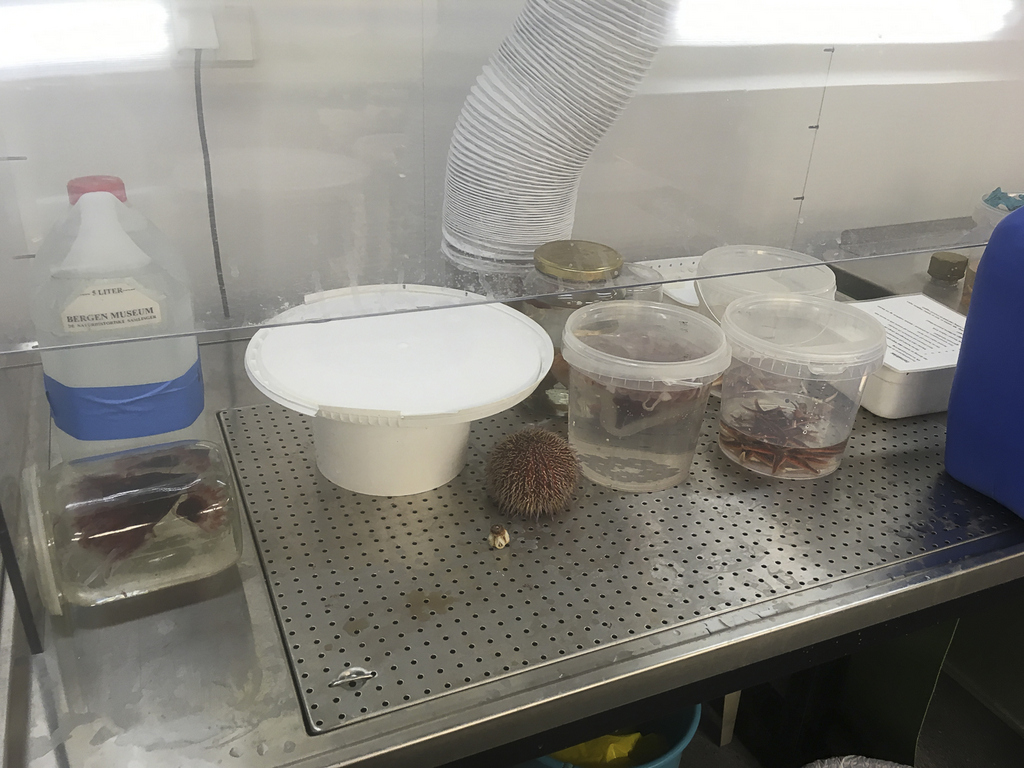

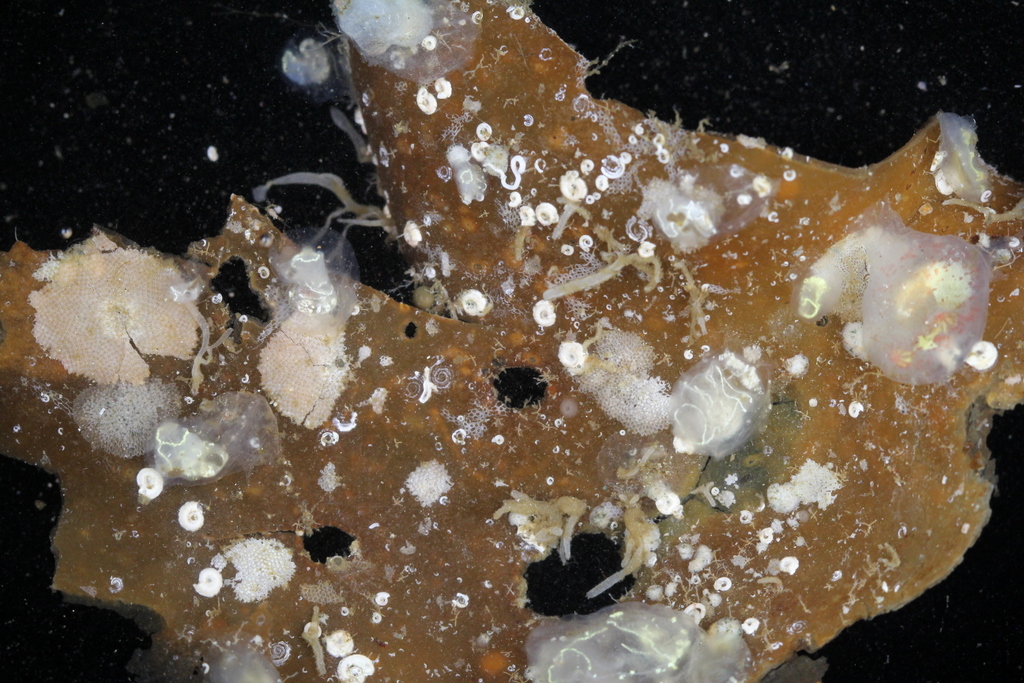

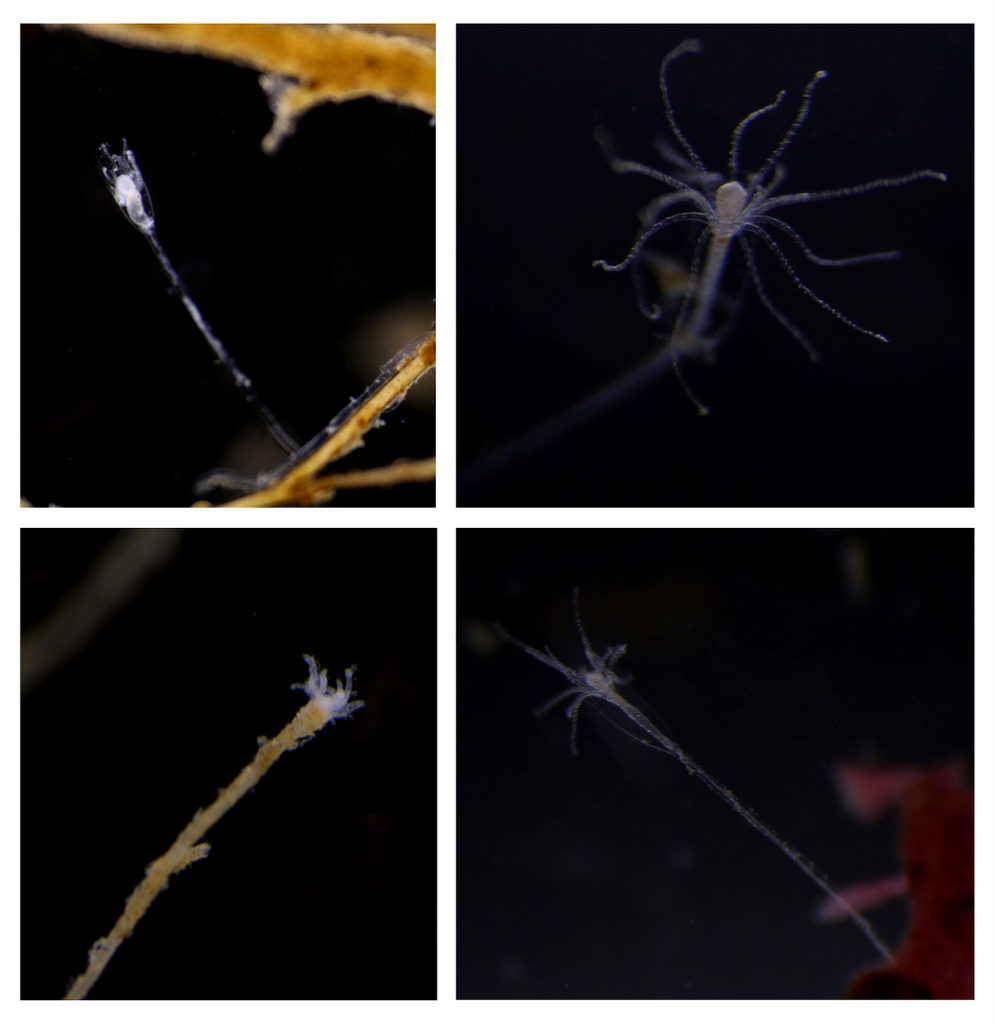

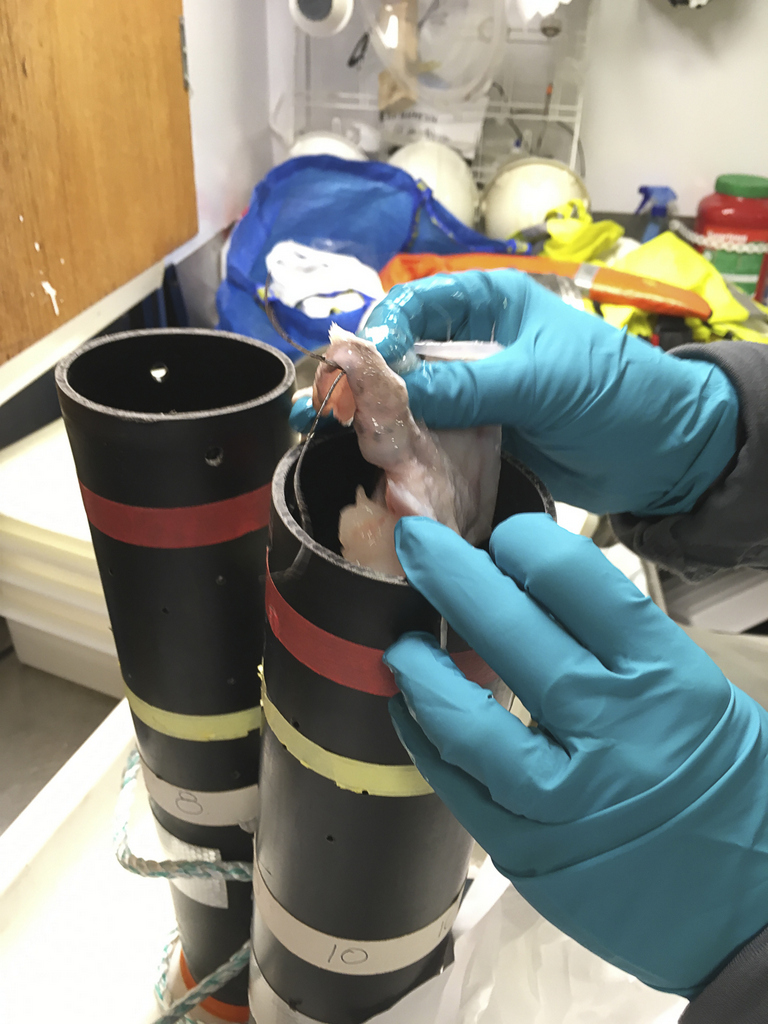

Last days in the lab: full house! The underwater film team: Mette and Jenny

Last days in the lab: full house! The underwater film team: Mette and Jenny