In November 2025, I got the chance to work closely together with Jon Kongsrud and Arne Hassel at the Invertebrate Laboratory of the Universitetsmuseet i Bergen on a sample set of pycnogonids collected by the MAREANO Programme (https://www.mareano.no). Norway’s museum collections hold immense information of the past and present biodiversity state, which are the basis for any faunistic research on the future development of the Arctic Ocean. As the oceans continue to warm, boreal and warm-water species are expanding their distribution range northwards – also called ‘borealisation’ or ‘Arctic Atlantification’. This phenomenon is known on Arctic shelves, but how will environmental changes affect the Arctic deep sea?

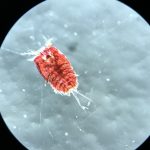

Before we can actually observe and describe shifts, we need to document the current status quo. Under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Saskia Brix (University of Hamburg) and Prof. Dr. Bodil Bluhm (Universitetet i Tromsø), I am investigating in my PhD the taxonomic and genetic biodiversity of boreal and Arctic deep-sea fauna as part of the “ALONGate” project (“A Longterm Observatory of the North Atlantic Gateway to the Arctic”). To cover different trophic levels of the food-web, my taxonomic focus is on the commonly called hooded shrimps (Cumacea) and sea spiders (Pycnogonida). While most cumaceans are detritus feeders and smaller than 1 cm, sea spiders are usually predators and can easily be detected with the bare eye, reaching a leg span of up to 30 cm in the Arctic (Fig. 1). Both are benthic taxa living associated with the seafloor and share a brood-caring lifestyle, which results in lower dispersal abilities compared to taxa with planktonic larvae.

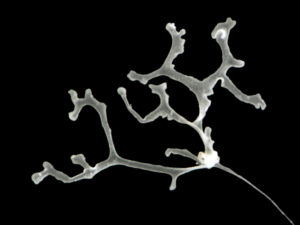

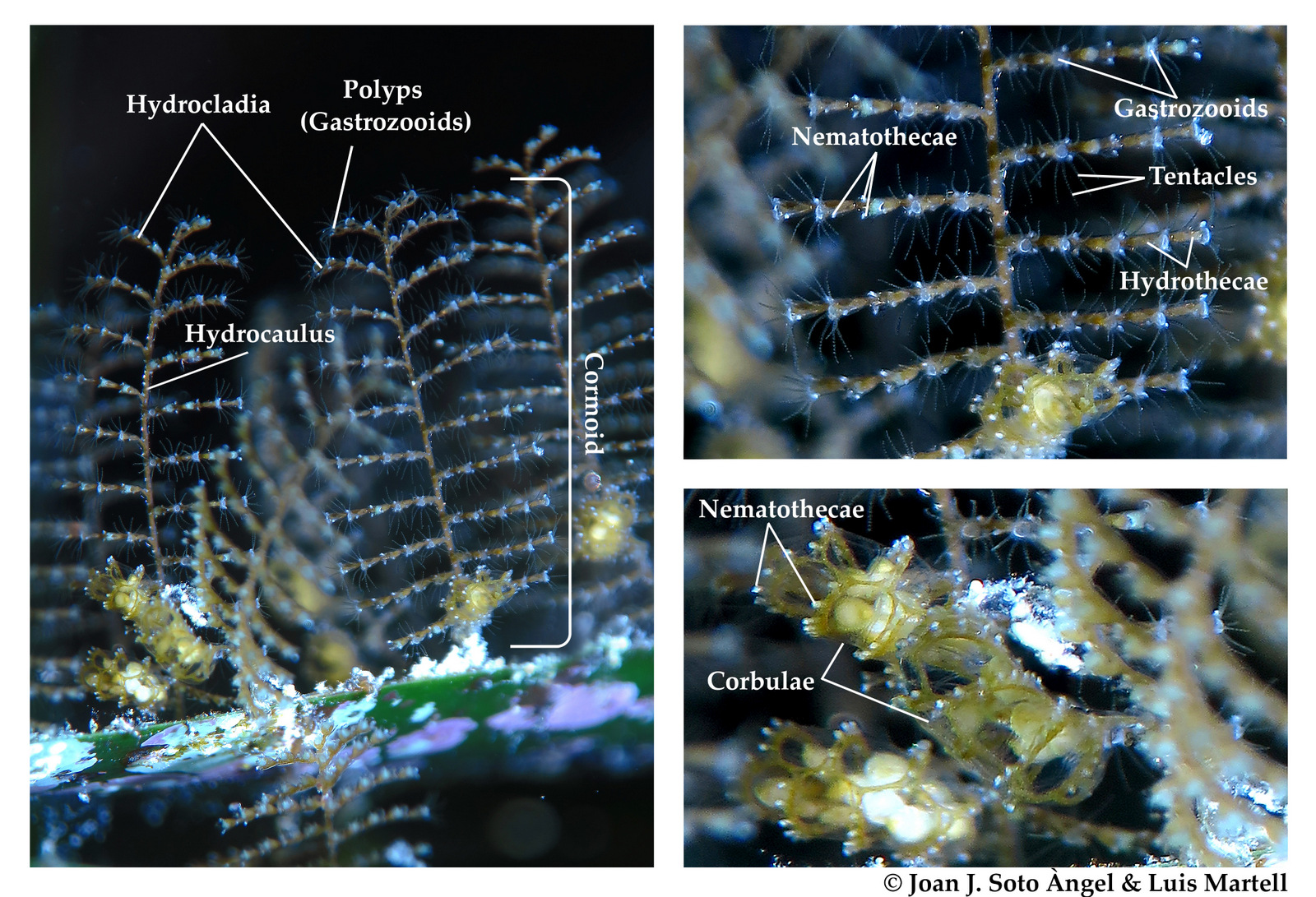

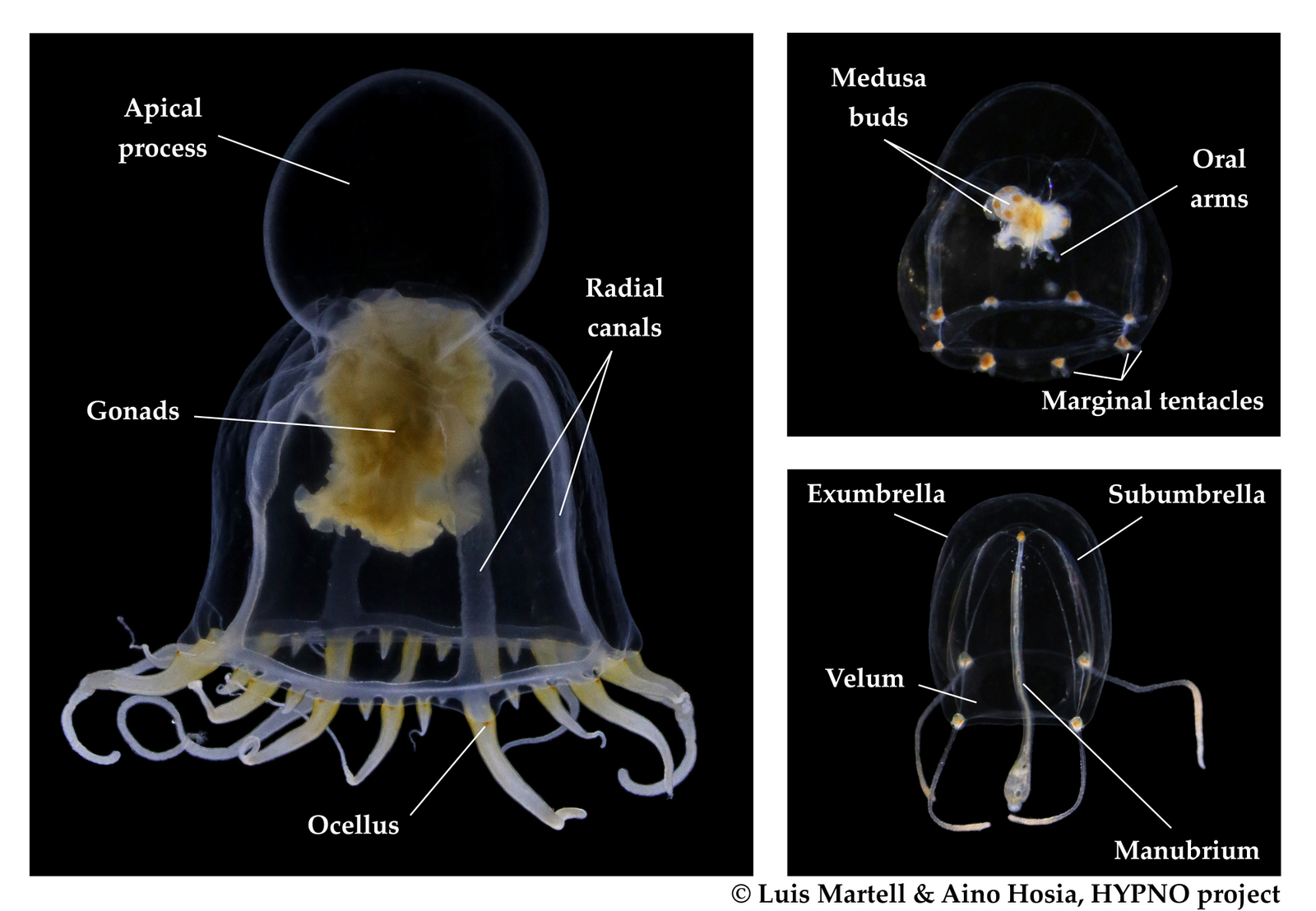

What fascinates me most about pycnogonids is the way their peculiarities come together. They are made out of limbs connected to a trunk and compensate their minimalistic bodies with housing most organs in their legs (Brenneis et al. 2017 called them the ‘no-bodies’). Basically, they breathe through their legs, while their gut acts as a heart. Most species live predatory using their massive proboscis like a straw to suck out soft bodied, sessile prey such as sponges or anemones while they are still alive, just like mosquitoes (Fig. 2).

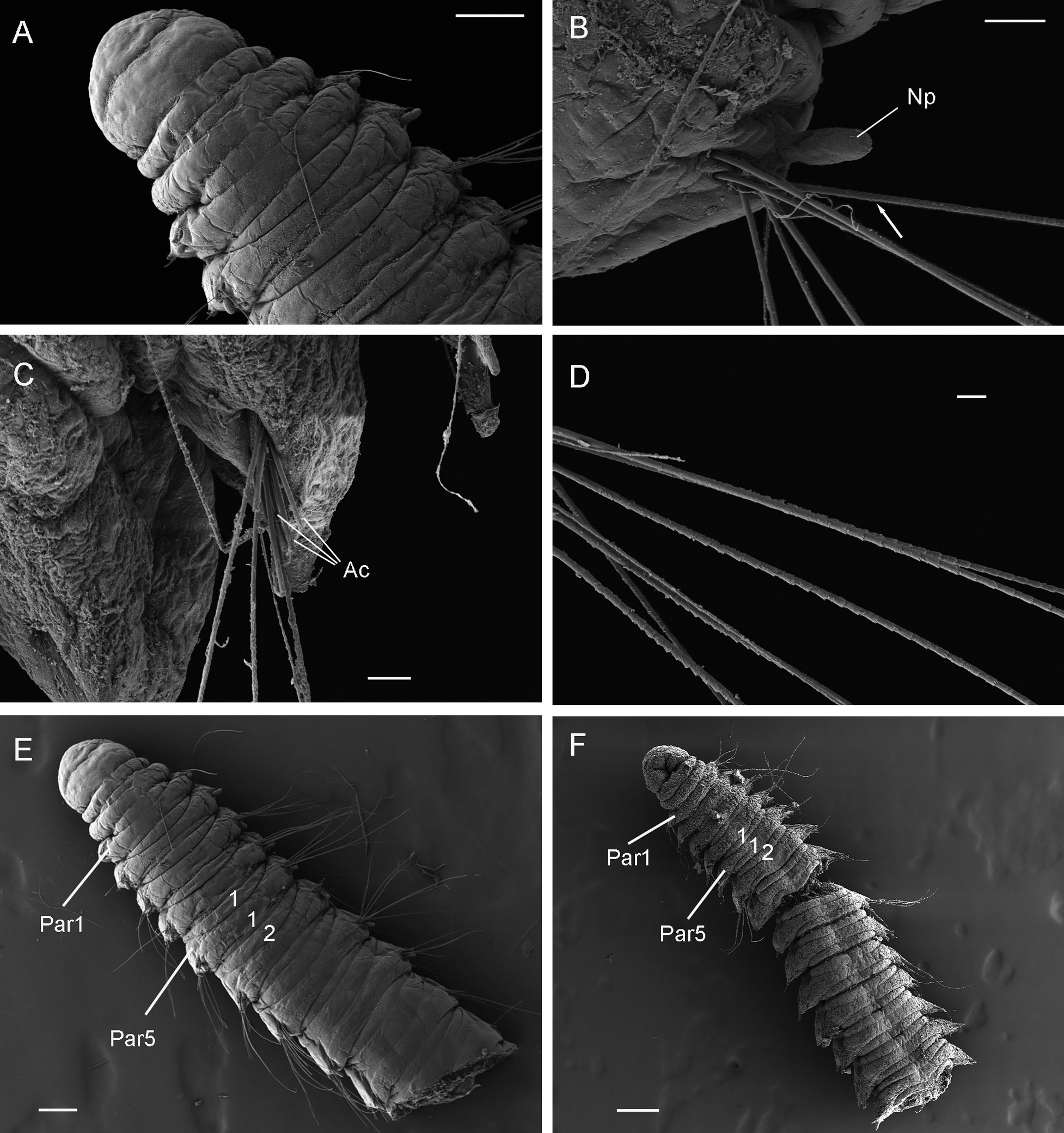

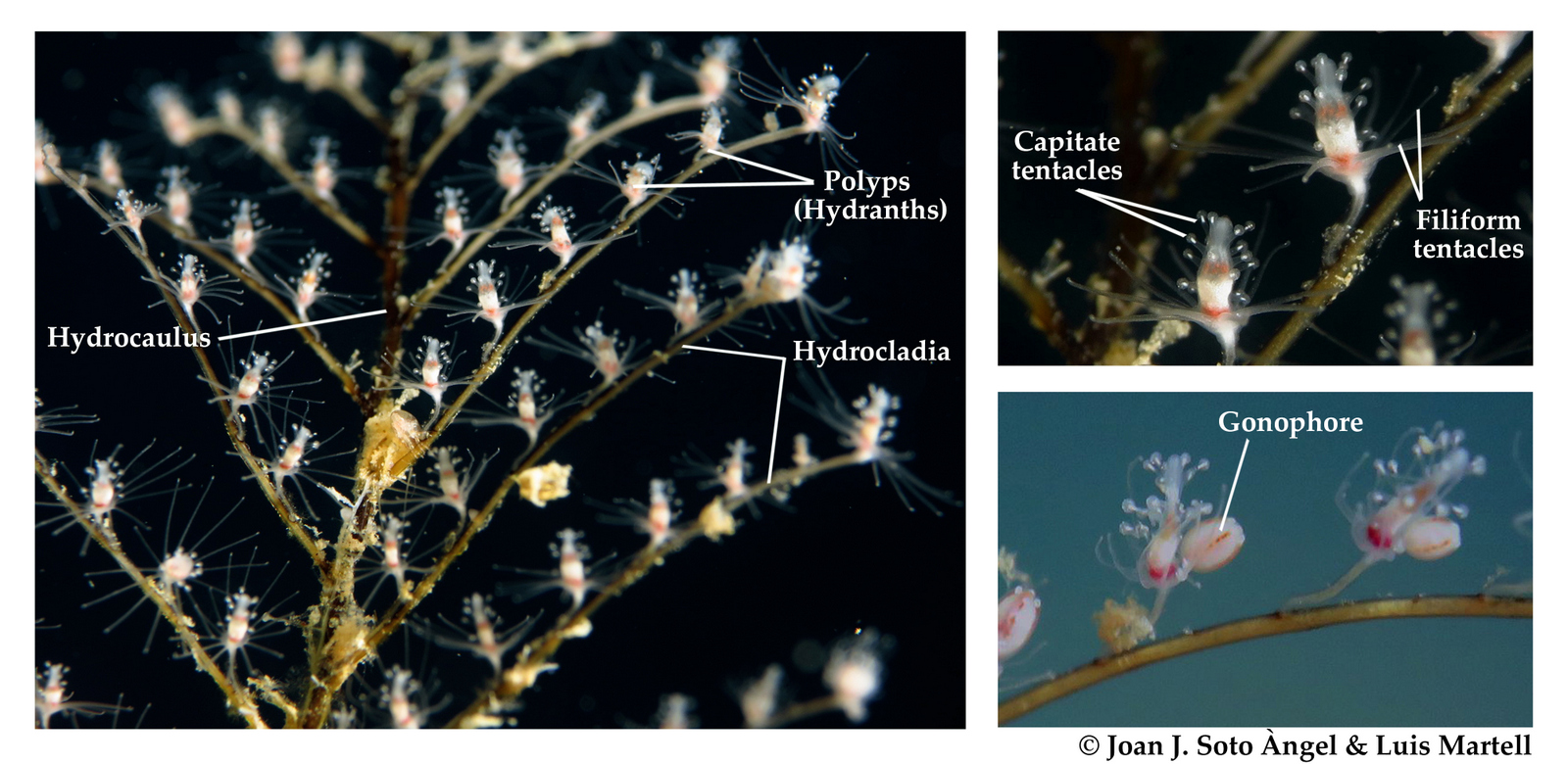

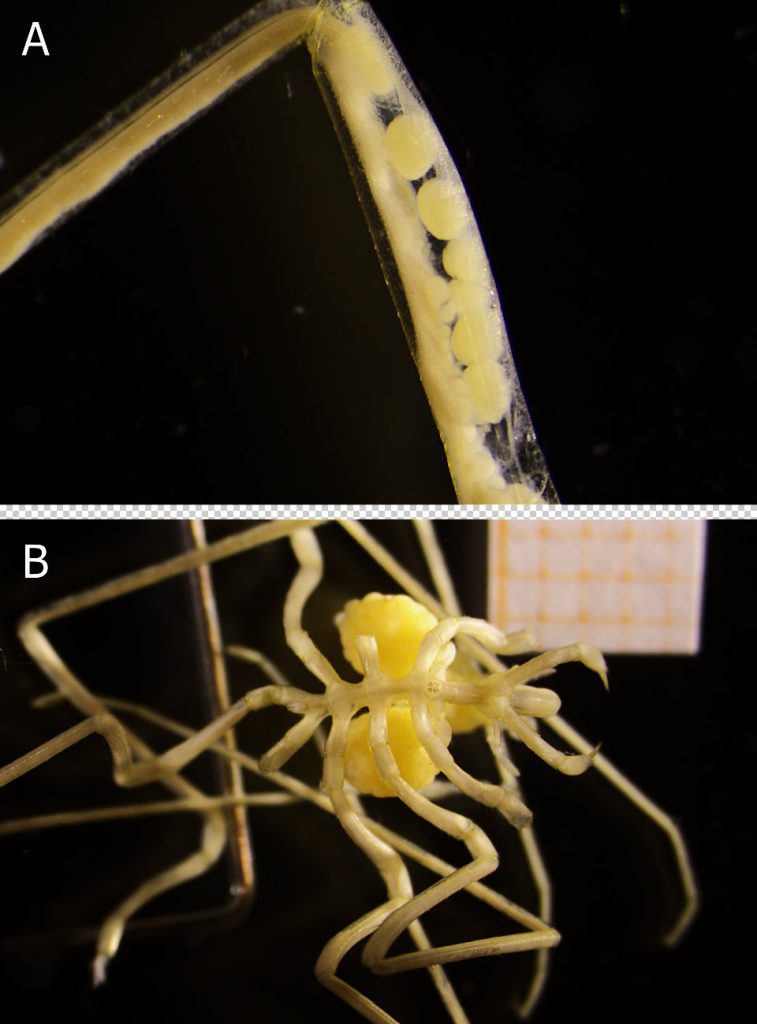

Even though pycnogonids are evolutionarily seen an old lineage, their parental brooding responsibility cannot be more modern: The female grows eggs in her swollen, muscular legs (Fig. 3A). While mating, the eggs are fertilised externally and then transferred to the male. He glues them as egg-masses to his ovigerous legs (Fig. 3B) and, after the embryos hatch, he carries them until they leave as young juveniles. This paternal brooding strategy sounds strange, but makes perfectly sense as it maximizes the offspring survival, increases the chances for multiple mating partners during a breeding season and allows the female to invest more energy in egg production (Bain & Godvich 2004).

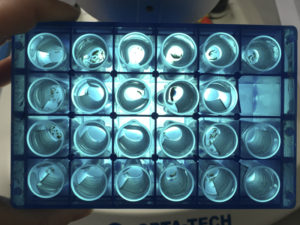

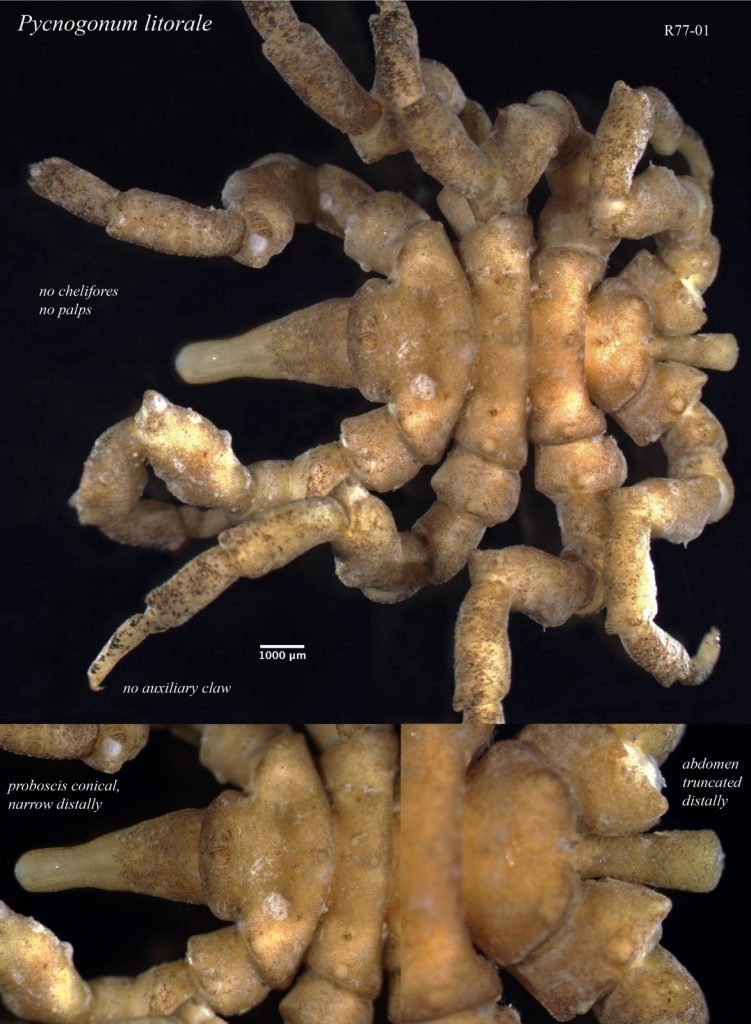

The goal of my research visit was to identify sea spider specimens catalogued in the museum collection, ground-truth previous taxonomic identifications and check their congruence with the results of genetic barcoding. Within about 300 individuals, we could distinguish 32 morphologically distinct species from shallow waters close to the Norwegian shore (e.g. Pycnogonum litorale (Strøm, 1762), Fig. 4) and the Arctic deep-sea beyond 4000 m depth (e.g. Ascorhynchus abyssi Sars, 1877, Fig. 5).

Our international collaboration will contribute to a current status-quo inventory of pycnogonid species in boreal, Sub-Arctic and Arctic waters, following up the research by Ringvold et al. (2015). We will discuss the morphological and genetic diversity of sea spiders, how their communities are structured across different habitats and regions. We expect this comprehensive dataset to enable us matching species to their preferred habitats and biotopes. This will provide fundamental information for observing distribution shifts in how sea spiders respond to future changes in the ocean.

Besides the valuable scientific input, I particularly appreciated the hospitable atmosphere and would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jon for our long-standing, trust-based collaboration and his exceptional scientific insight; to Arne, who generously shared his passion and profound knowledge about sea spiders from Norwegian waters; to Irina Zhulay, Nataliya Budaeva, Katrine Kongshavn, Rebecca Ross, Yngve Johansen, Kjell Bakkeplass, Kenneth Meland, Brenda Lizbeth Esteban and Christian Ludvig Nilsson for their warm welcome, support and the inspiring discussions. I look forward to further teamwork!

Carolin Uhlir

Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (SGN)

Bain, B.A., & Govedich, F.R. (2004). Courtship and mating behavior in the Pycnogonida (Chelicerata: Class Pycnogonida): a summary. Invertebrate reproduction & development, 46(1), 63-79.

Brenneis, G., Bogomolova, E.V., Arango, C.P., & Krapp, F. (2017). From egg to “no-body”: an overview and revision of developmental pathways in the ancient arthropod lineage Pycnogonida. Frontiers in Zoology, 14(1), 6.

Ringvold, H., Hassel, A., Bamber, R.N., & Buhl-Mortensen, L. (2015). Distribution of sea spiders (Pycnogonida, Arthropoda) off northern Norway, collected by MAREANO. Marine Biology Research, 11(1), 62-75.