We greet December with our 2016 edition of the invertebrate advent calendar, and will be posting a new blog post here every day from today until the 24th of December! Be sure to check in often! All posts of this year’s calendar will be collected here: 2016 calendar, and all of the post in last year’s event are gathered here in case you would like a recap: 2015 edition. First out is Anne Helene and a Northern amphipod:

December is over us, the Advent Calendar from the invertebrate section lets you open the first door today, and many children (both small and slightly older) are eagerly awaiting the answer to their letter to Santa Claus. Mr Claus is supposed to live on the North Pole, and many letters addressed there have been coming through different post-offices the last months.

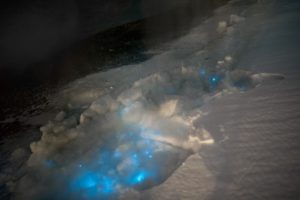

Many of us are wondering if Santa Claus might be a Species dubius (a species it is slightly doubtful exists), but if he exists, his homestead is becoming endangered. We are seeing a rapid decline of the Arctic sea ice (here is a video from NOAA showing the extent and age of the icecap from 1987 to 2014), and this will undoubtedly have a large effect on the Earths climate.

A polar bear mother and cub walking on the top of the sea ice. Photo: AHS Tandberg

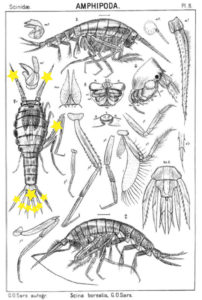

In addition to the theoretical possibility of Santa, there are several true and precious species that depend on the sea ice for their life. Most probably think about polar bears and seals now, but there is an even more teeming abundance of life right under the ice, many of them live as the sea ice is an upside-down seafloor. The largest animal biomass of all the many invertebrate species connected to the sea ice (we call these sympagic species), comes form the amphipod Gammarus wilkitzkii Birula 1897.

Gammarus wilkitzkii is the largest of the invertebrates that hang out (literally) under the ice; they can reach almost 3 cm length. They are whitish-grey, with red-striped, long legs. The hind legs have hooks that allow them to easily attach to the sea ice, and hanging directly under the ice instead of swimming saves a lot of energy for them. This behaviour is so necessary to them that if we keep them in an aquarium, they need something to hang on to – be it the oxygen-pump, a piece of styrofoam, the hand of a researcher or the edge of the lid. There are a few observations of swimming G. wilkitzkii sampled from the middle of the water-column, but this seems to be specimens that have lost their hold in life – we do not think they can live long swimming around (that would take too much energy).

A male (white) Gammarus wilkitzkii holding a female (yellow) Gammarus wilkitzkii. The male is also holding on to the sea-ice with his hind legs. Photo: Bjørn Gulliksen, University of Tromsø and UNIS.

Being such large animals, and in such large abundance, G. wilkitzkii are preyed upon mostly by diving sea-birds, but they have also been found in the stomach-content of harp-seals and to a small degree the small and stealthy polar cod. Most of these animals are mainly found in what we call the marginal ice zone – where the sea ice meets the open water. This is also the place where G. wilkitzkii can find most of its own food: algae, other small invertebrates and ice-bound detritus.

A diver under the sea ice. Photo: Geir Johnsen, NTNU

G. wilkitzkii is also found in great quantities under the multi-year ice, where it probably leads a safer life. Being at the edge of the ice presents a problem: this is the ice that melts during the summer, and that will force the amphipods to move further into the ice as its habitats disappear. The underside of the ice is not a flat field – it is a labyrinth of upside-down mountains and valleys, with several small and large caves. Many nice hiding-places, but if you swim or crawl along the ice-surface, the distance is longer than we would measure it on the top of the ice.

Where the ice is thin, or where there is no snow covering the ice, some light will shine through. This means that the edge of the ice normally lets a lot more light through than the multi-year ice. We dont know what this does for G. wilkitzkii, but they have eyes that are of similar size and shape as the other species in the genus, so they possibly use their eyes for hunting for food or checking for enemies.

-

-

Ice-floats and more permanent ice. Svalbard. Photo: AHS Tandberg

-

-

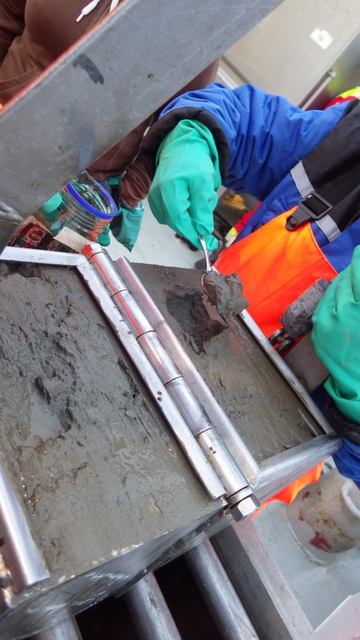

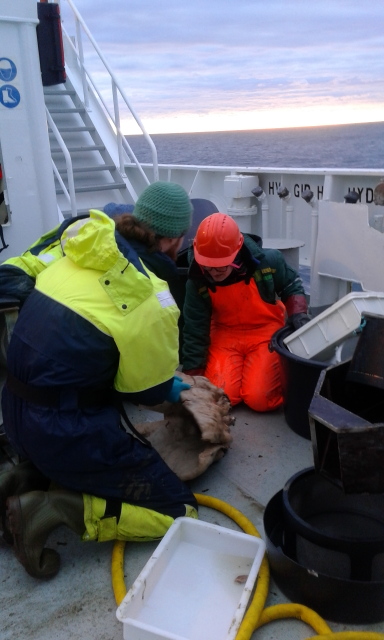

A diver gets ready to sample Gammarus wilkitzkii under the sea ice. Photo: AHS Tandberg

is an animal that is accustomed to a tough life. The sea temperature right under the ice normally lies around -1.8ºC, (so below what we think of as “freezing”) this is because of the high salinity of the water. As sea-water freezes, the salt leaks out, and flows in tiny brine-rivers trough the ice and down into the water below. They have specialised their life cycle to fit with the available food – so that their young are released when there is much food to be found, and they can live up to 6 years reproducing once every of the last 5 years, probably to make sure at least some of their offspring survive.

We have 24 more days before we find out if Santa “exists”, though this might not give us the answer to him having become a climate-refugee. Hopefully, we will have to wait much longer to find out what will happen with the many ice-dependent invertebrates, but becoming climate-refugees might not be easily accomplished for them.

Anne Helene

Literature:

Arndt C, Lønne OJ (2002) Transport of bioenergy by large scale arctic ice drift. Ice in the environment – Proceedings of the 16th IAHR International Symposium on Ice, Dunedin , NZ. p103-111.

Gulliksen B, Lønne OJ (1991) Sea ice macrofauna in the antarctic and the Arctic. Journal of Marine Systems 2, 53-61.

Lønne OJ, Gulliksen B (1991) Sympagic macro-fauna from multiyear sea-ice near Svalbard. Polar Biology 11, 471-477.

Werner I, Auel H, Garrity C, Hagen W (1999) Pelagic occurence of the sympagic amphipod Gammarus wilkitzkii in ice-free waters of the Greenland Sea – dead end or part of life-cycle? Polar Biology 22, 55-60.

Weslawski JM, Legezinska J (2002) Life cycles of some Arctic amphipods. Polish Polar Resarch 23, 2-53.

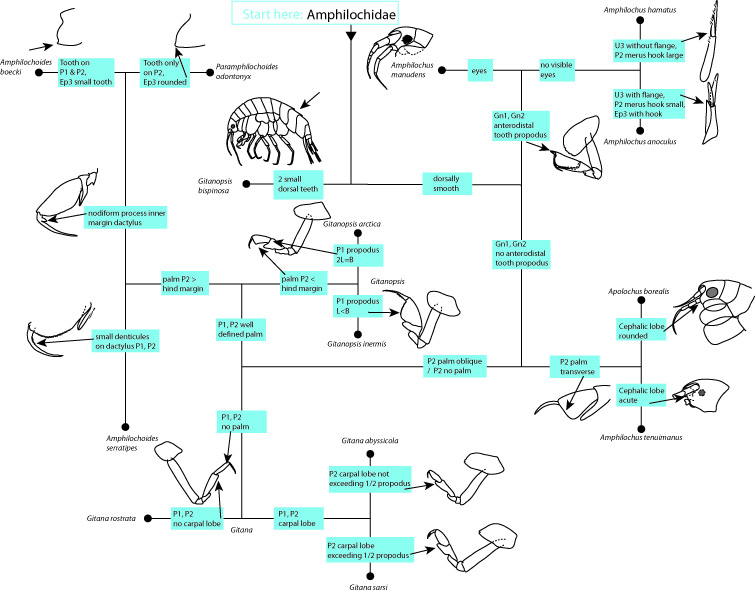

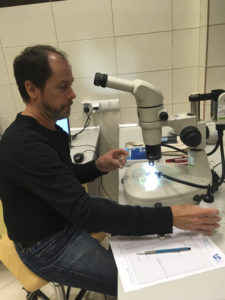

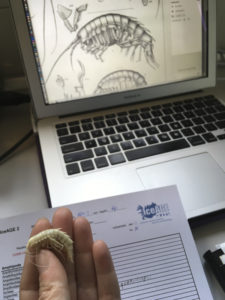

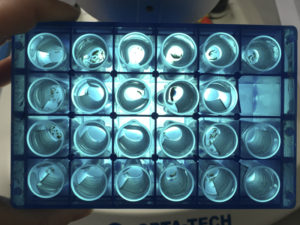

The key is a product of a collaboration between the NorAmph-project and the German-lead IceAGE project that examines benthic animals around Iceland, and the technical production and web-hosting of the key is from the Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative (Artsprosjekt) (who – we have to say – also have financed the NorAmph-project!) Hurrah for a great collaboration!

The key is a product of a collaboration between the NorAmph-project and the German-lead IceAGE project that examines benthic animals around Iceland, and the technical production and web-hosting of the key is from the Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative (Artsprosjekt) (who – we have to say – also have financed the NorAmph-project!) Hurrah for a great collaboration!