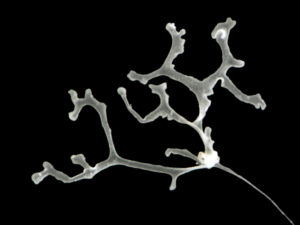

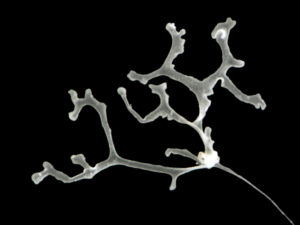

Bircenna thieli seen from the front and the side. SEM photo, Fig 6 in Hughes and Lörz, 2019.

This question (or a version of it) is something a lot of us taxonomists are faced with quite often when we try to explain what we do for a living. And I do understand the need to ask – couldn´t our talents be used better doing something it might be easier to understand the use of? We think the study of taxonomy is higly important, and does bring about useful knowledge for the world. Therefore, we have several taxonomic projects in our group, and we write about them here in the blog. (If you read norwegian, you can read about our projects here)

March 19th was the world Taxonomist Appreciation Day – a day we have “celebrated” since 2013. Why do we need this day? Taxonomy is the science of naming, defining, describing, cataloguing, identifying and classifying groups of biological organisms. We do this in labs and on fieldwork, and the natural history museums (these days represented from our home offices) have a special responsibility for this work, since one part of the formal description of a taxon is to designate a type and store that in a museum collection. We will come back to the importance of types in a later blog here.

Terry McGlynn, the professor and blogger who initiated the Taxonomist Appreciation Day wrote: ” I want to declare a new holiday! If you’re a biologist, no matter what kind of work you do, there are people in your lives that have made your work possible. Even if you’re working on a single-species system, or are a theoretician, the discoveries and methods of systematists are the basis of your work. Long before mass sequencing or the emergence of proteomics, and other stuff like that, the foundations of bioinformatics were laid by systematists. We need active work on taxonomy and systematics if our work is going to progress, and if we are to apply our findings. Without taxonomists, entire fields wouldn’t exist. We’d be working in darkness.”

Every year a large number of new taxa are described – last year almost 2000 of the new species described were marine. March 19th every year, the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) and LifeWatch publish their favourite 10 marine species described in the previous year, and this year – corona-shutdown and all – was no exception.

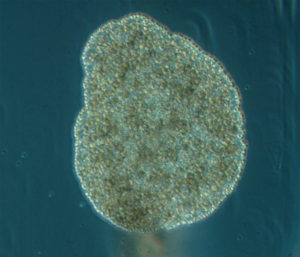

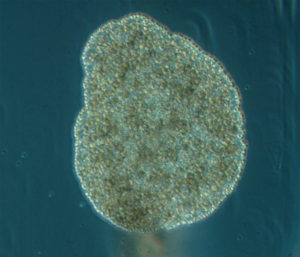

All ten new species are fun, beautiful and remarkable – but Polyplacotoma mediterranea Osigus & Schierwater, 2019 deserves special mentioning. P. mediterranea is the third species described ever in the phylum Placozoa – who are viewed as one of the key-taxa to understand early animal evolution. They were first described in 1883 (by Schulze), and the name Placozoa indicated what they looked like: small (around 1 mm for the largest of the specimens) platelike animals. 2018 saw the second species of placozoans described – genetically, as it was impossible to separate morphologically – but then our new placozoan came – and it is 10mm large, is branched, and has its natural habitat in the mediterranean intertidal! Phylum Placozoa will never be the same again, and our understanding of the early evolution of animals has become even more interesting.

-

-

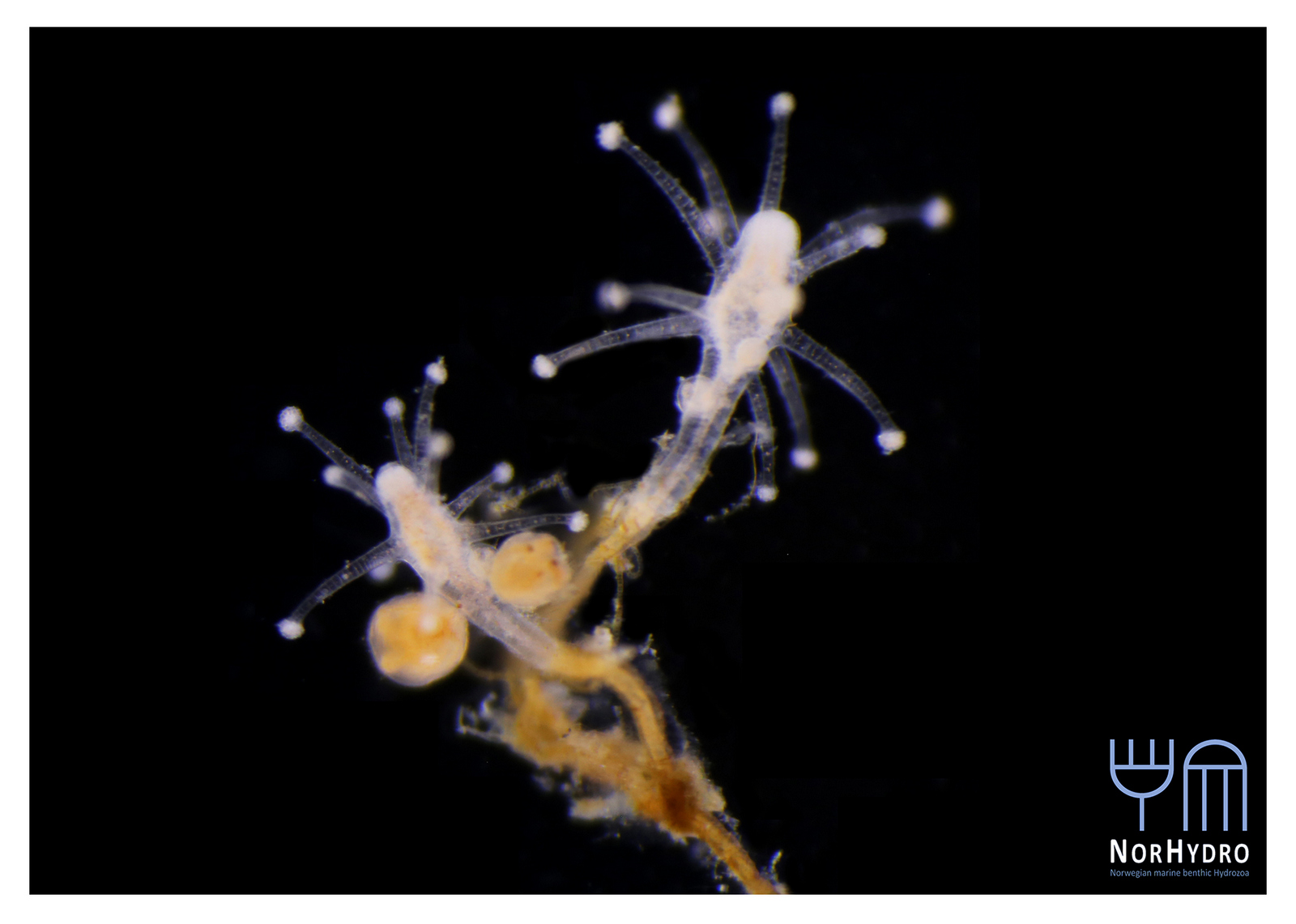

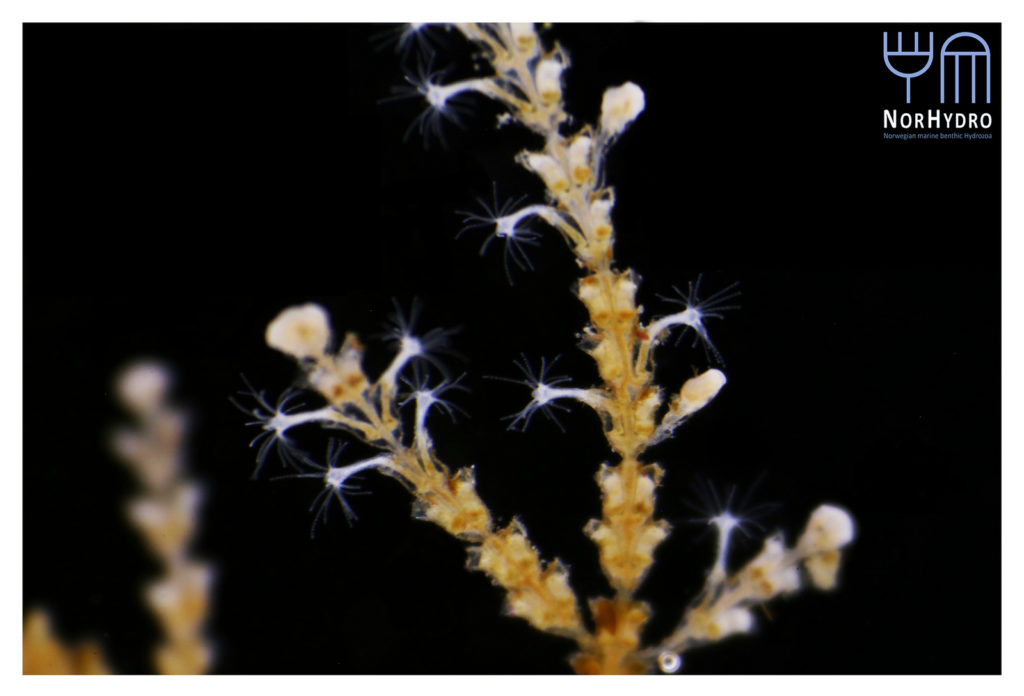

Polyplacotoma mediterranea. Photo by Hans-Jürgen Osigus, Schierwater lab, Stiftung Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover (cc-nc-sa)

-

-

Trichoplax adhaerens Schulze, 1883 Photo by Bernd Schierwater in Eitel M, Osigus H-J, DeSalle R, Schierwater B (2013) this animal is 0.5 mm in size.

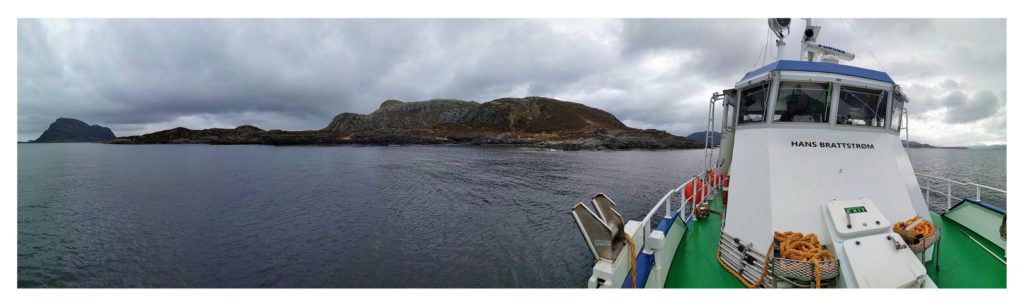

What then about the boring amphipods? Or course they are not boring as in saying they are dull! The “boring amphipod” Bircenna thieli Hughes & Lörz, 2019 bores in the sense that they excavate tunnels into the stem of the common bull kelp Durvillaea potatorum (Labillardière) Areschoug, 1854 in the intertidal and shallow waters by Tasmania.

-

-

Bull kelp, Durvillaea potatorum (Labillardière) Areschoug, 1854. Photo by Peter Southwood – CC BY-SA 3.0

-

-

Bircenna spp. in their habitat: boring into Durvillaea potatorum in Tasmania. Fig. 9 from Hughes and Lörz 2019.

-

-

Bircenna thieli Fig 4 from Hughes and Lörz, 2019

Bircenna thieli has a head almost like an ant, and a quite unusual shape of its back-body. Fig 8 from Hughes and Lörz, 2019

Their head has an ant-like ball-shape unlike many other amphipods where the head is more ornate or has a visible rostrum, but the exciting morphology comes at the other end of the animal – where the telson and last segment have structures never seen before in amphipods, and structures that only other vegetation-boring amphipods show.

So why do we think describing tiny animals, plants, fungi, bacteria and other organisms is so important? Let us ask you back: how can you appreciate what you have and care about what might be lost if you dont know who they are?

Anne Helene

(this post was written March 19th, but posted later..)

Literature:

Eitel M, Osigus H-J, DeSalle R, Schierwater B (2013) Global Diversity of the Placozoa. PLoS ONE 8(4): e57131. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057131

Hughes, L.E.; Lörz, A.-N. (2019). Boring Amphipods from Tasmania, Australia (Eophliantidae: Amphipoda: Crustacea). Evolutionary Systematics 3(1): 41-52. https://doi.org/10.3897/evolsyst.3.35340

Osigus, H.-J.; Rolfes, S.; Herzog, R.; Kamm, K.; Schierwater, B. (2019). Polyplacotoma mediterranea is a new ramified placozoan species. Current Biology 29(5): R148-R149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.068

Do you want to find out more about Taxonomist Appreciation Day or about all the 10 exciting species?

Ten remarkable new marine species from 2019

Today is Taxonomist Appreciation Day!

A compendium of taxonomists on ORCID

and not least – you can still follow the #TaxonomistAppreciationDay on Twitter (and be prepared for 2021!)