Yesterdays door of this calendar introduced the bioluminescent animals of the deep sea.

In the parts of the ocean where sunlight reaches (the photic zone), production of ones own light is not common. This is because it is costly (energetically), and when the surroundings already are light, the effect is almost inexistent. An exception to this is the use of counter-illumination that some animals have: lights that when seen from underneath the animal camouflages them against the downwelling light from above.

But what then with the ocean during the polar night? Last Thursdays blog told the story of the dark upper waters during the constant dark of the arctic winter, and how the quite scanty light of the moon is enough to initiate vertical mass movements. Another thing we see in the dark ocean is that processes that at other latitudes are limited to the deep sea come up nearly to the surface during the polar night.

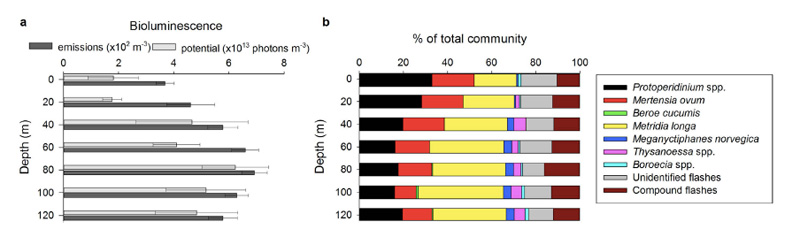

So – in the Arctic winter we don´t have to use robots and remote cameras to observe biioluminescent animals: we can often observe them using normal sport diving equipment or even from above the surface. A very recent study (Cronin et al, 2016) has measured the light from different communities in the Kongsfjord of Svalbard during the polar night. They found that going from the surface and down, dinoflagellates produced most light down to 20-40 m depth, the lighting “job” was then in general taken over by small copepods (Metridia longa). Most light was produced around 80 m depth.

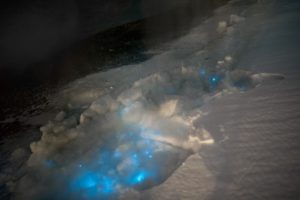

Bioluminescent dinoflagellates shining through the winter sea ice in Kongsfjorden. Photo: Geir Johnsen, NTNU

It is possible to recognise different species from the light they make; a combination of the wavelength, the intensity and the length of the light-production gives a quite precise “thumbprint”. If we know the possible players of the system in addition, an instrument registering light will also be able to give us information about who blinks most often, at what depths, etc. Cronin and her coauthors have made a map of the lightmakers in the Kongsfjord.

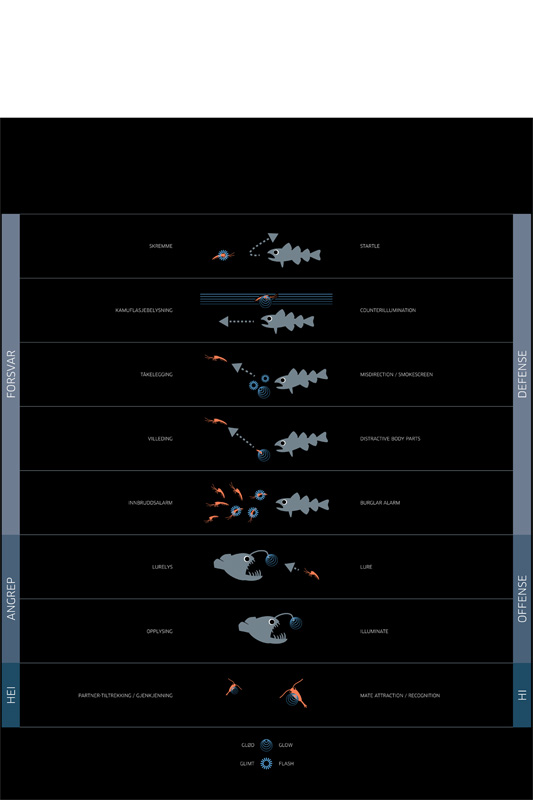

This is all well and good, but the next question is of course WHY. There can be several uses for light, and we can bulk the different reasons into 3 main groups: Defense, offense and recognition.

Different strategies for Bioluminescence. Fig 7 from Haddock (2010), redrawn for representation of the Polar night bioluminescence by Ola Reibo for the exhibition “Polar Night”

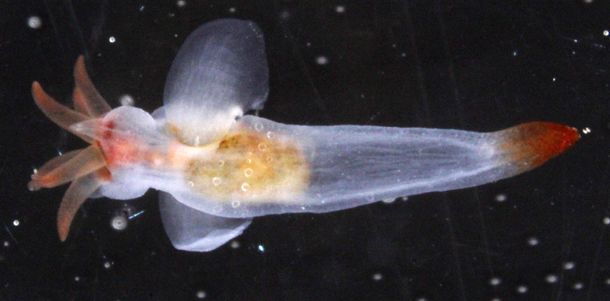

The bioluminescent cloud from an escaping krill. Kongfjorden, during the Arctic polar night. Photo: Geir Johnsen, NTNU

Defence has already been mentioned above: the counterillumination against downwelling light is helping an animal defend itself against predation. Some will leave a smokescreen, or even detach a glowing bodypart while swimming away in the dark, and others blink to startle the enemy or to inform their group-mates that an enemy is getting close.

Offense is mainly to use the light to get food (this is typical angler-fish-behaviour), and recognition is very often about flirting. Instead of flashing your eyelashes at your your chosen potential partner, you flash some light at him or her…

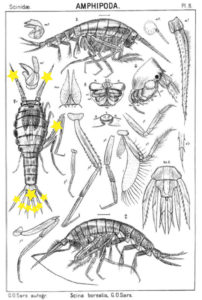

Thursdays are about amphipods in this blog, so here they come. Bioluminescent amphipods are present mainly in the hyperiid genera Scina (a Norwegian representative of this genus is Scina borealis (Sars, 1883).) Hyperiids are amphipods that swim in the free watermasses, like most other bioluminescent animals.

The bioluminescent amphipod Scina borealis (Sars, 1893). The added stars indicate where the bioluminescence occurs. Original figure: G.O.Sars, 1895.

Crustacea use more different ways to produce bioluminescence than most other groups – this points to a possibility that the use of bioluminescence has evolved several independent times in this group. So the copepod Metridia longa will use a different chemical reaction than the krill, and the amphipods use again (several) different reactions. Some research on the bioluminescence of amphipods was undertaken already in the late 1960s, where P Herring collected several Scina species and kept them alive in tanks. There he exposed them to several luminescence-inducing chemicals and to small electrical shocks, to see where on the body light was produced and in what sort of pattern. He reported that Scina has photocytes (lightproducing cells) on the antennae, on the long 5th “walkinglegs”, and on the urosome and uropods. They would produce a nonrythmical rapid blinking for up to 10 seconds if attacked, and at the same time the animal would go rigid in a “defence-stance” with the back straight, the antennae spread out in front of the head, and the urosome stretched to the back. This definitely seems to be a defence-ligthing, maybe we should even be so bold as to say it would startle a predator?

Anne Helene

Literature:

Cronin HA, Cohen JH, Berge J, Johnsen G, Moline MA (2016) Bioluminescence as an ecological factor during high Arctic polar night. Scientific Reports/Nature 6, article 36374 (DOI: 10.1038/srep36374)

Haddock SHD, Moline MA, Case JF (2010) Bioluminescence in the Sea. Annual Review of Marine Science 2, 443-493

Herring PJ (1981) Studies on bioluminescent marine amphipods. Journal of the Marine biological Association of the United Kingdoms 61, 161-176.

Johnsen G, Candeloro M, Berge J, Moline MA (2014) Glowing in the dark: Discriminating patterns of bioluminescence from different taxa during the Arctic polar night. Polar Biology 37, 707-713.