The final week of March was teeming with activity, as no less than three Norwegian Taxonomy Projects (Artsprosjekt) from the Invertebrate Collections arranged a workshop and fieldwork in the University of Bergen’s Marine biological field station in Espegrend.

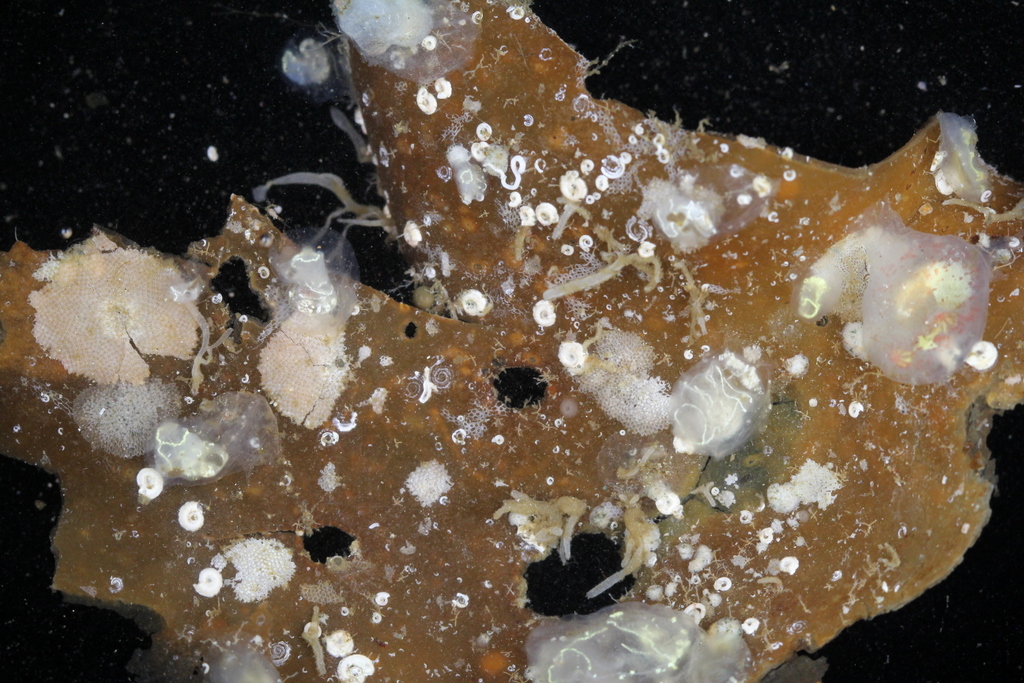

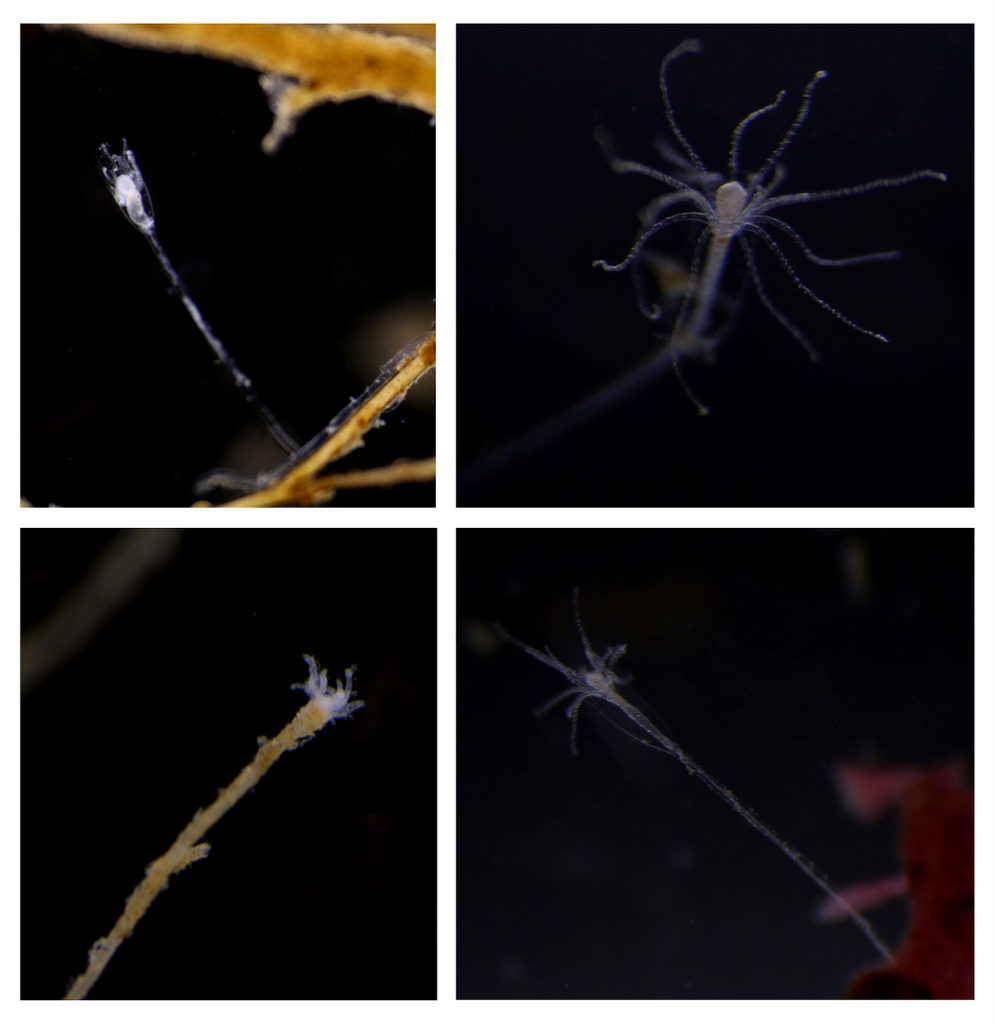

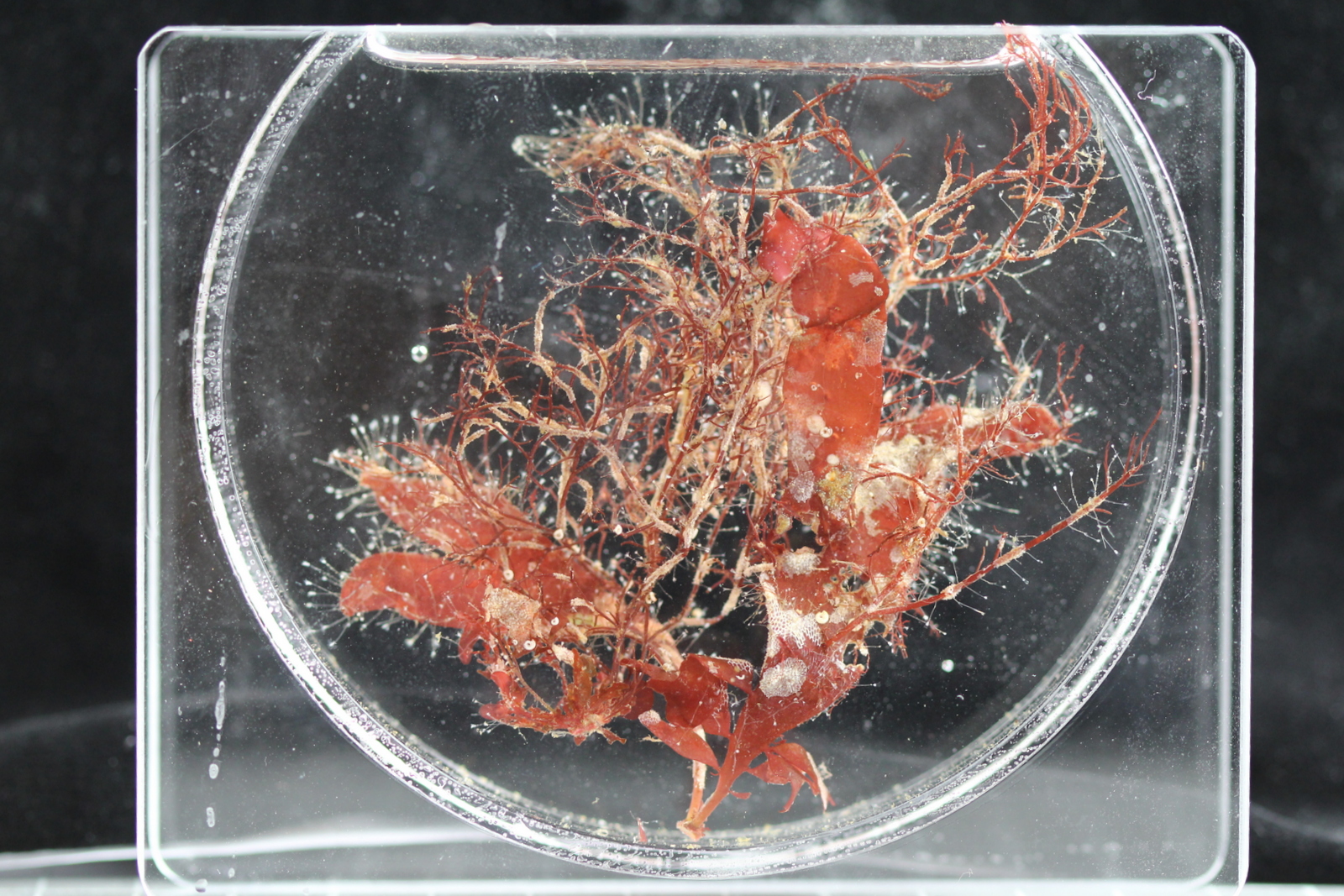

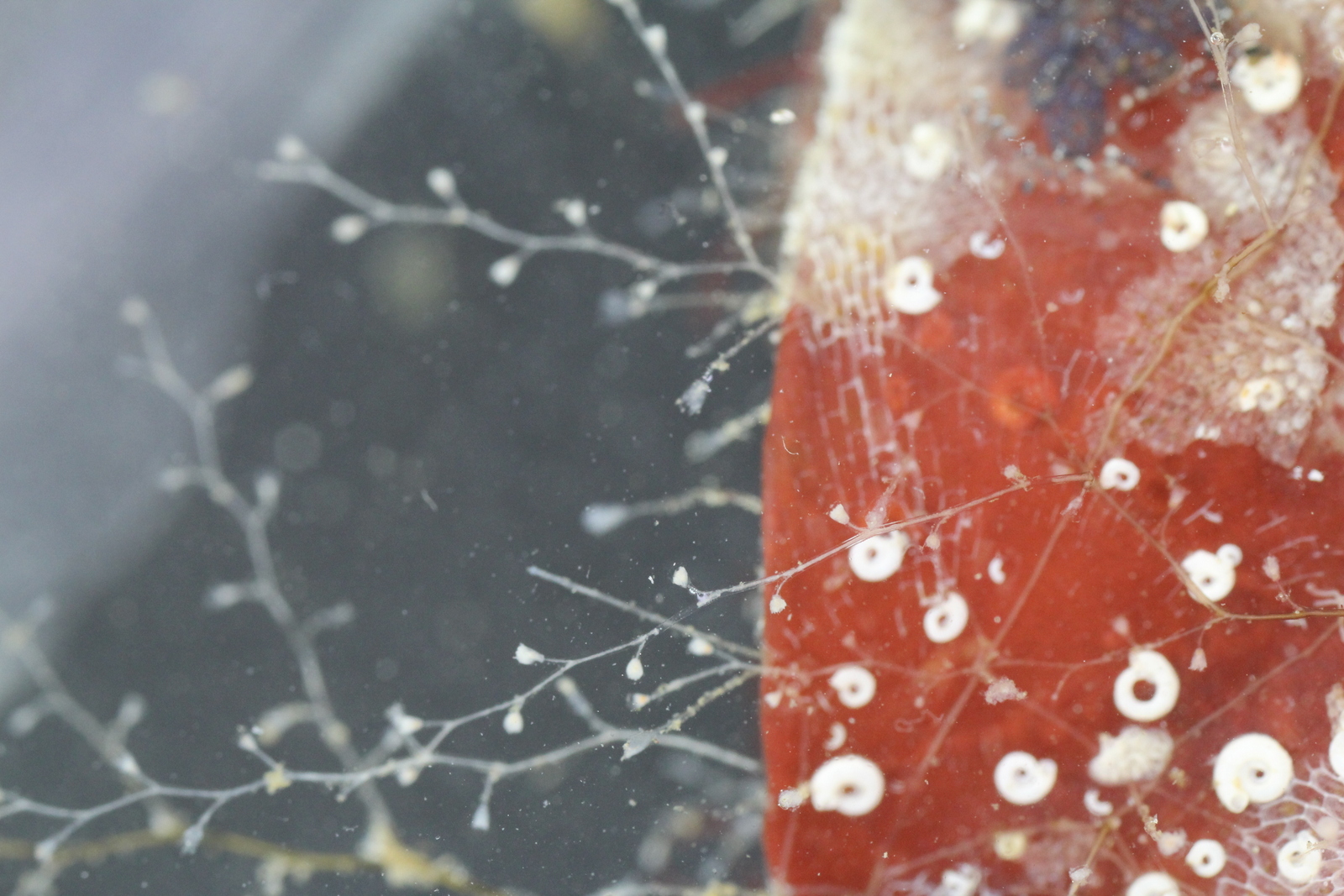

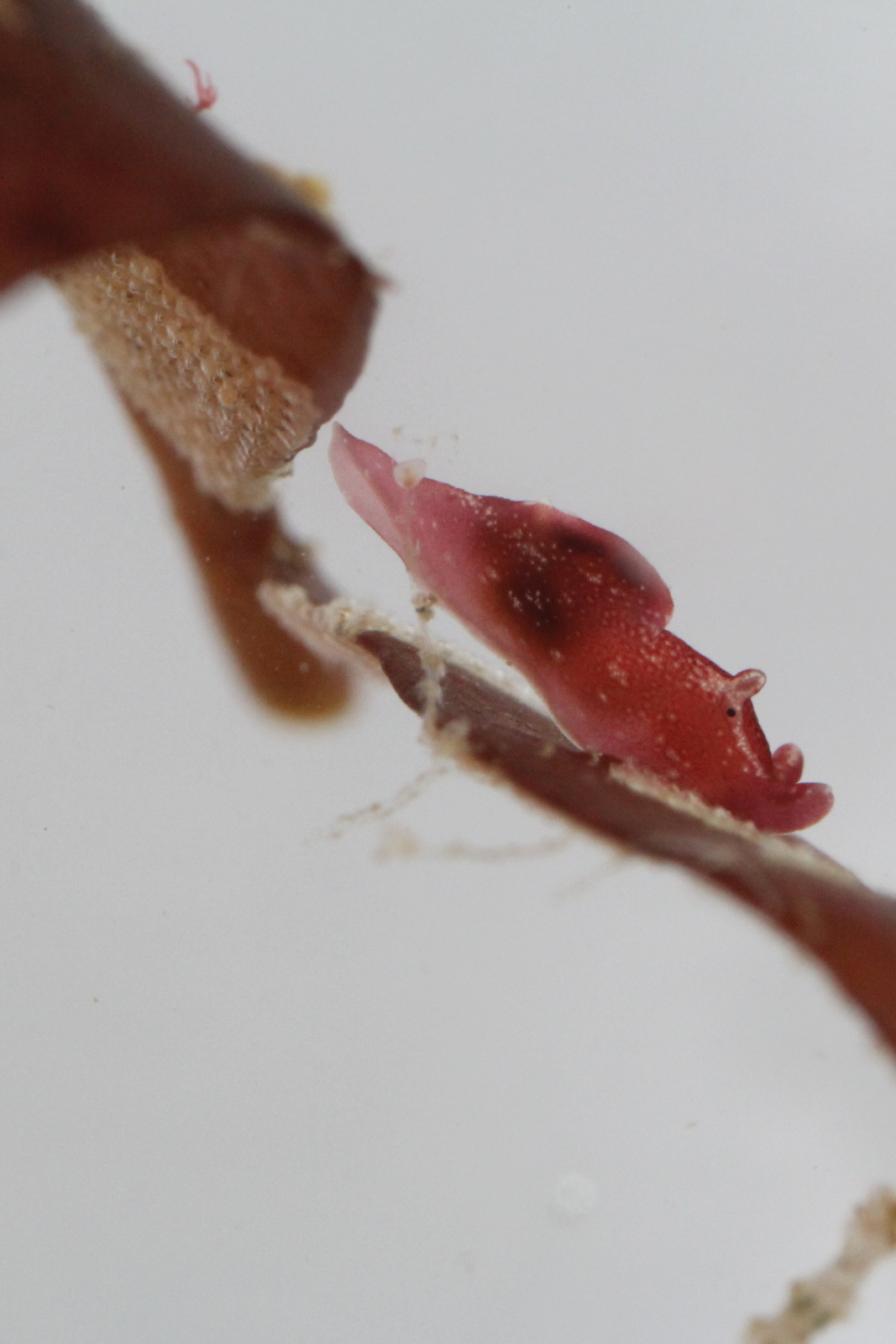

The projects – Sea Slugs of Southern Norway(SSoSN), Norwegian Hydrozoa (NorHydro) and Invertebrate fauna of marine rocky shallow-water habitats: species mapping and DNA barcoding (Hardbunnfauna) fortunately overlap quite a bit in where and how we find our animals (as in, Cessa’s seaslugs are eating the organisms the rest of us are studying..!), and so it made sense that we collaborated closely during this event.

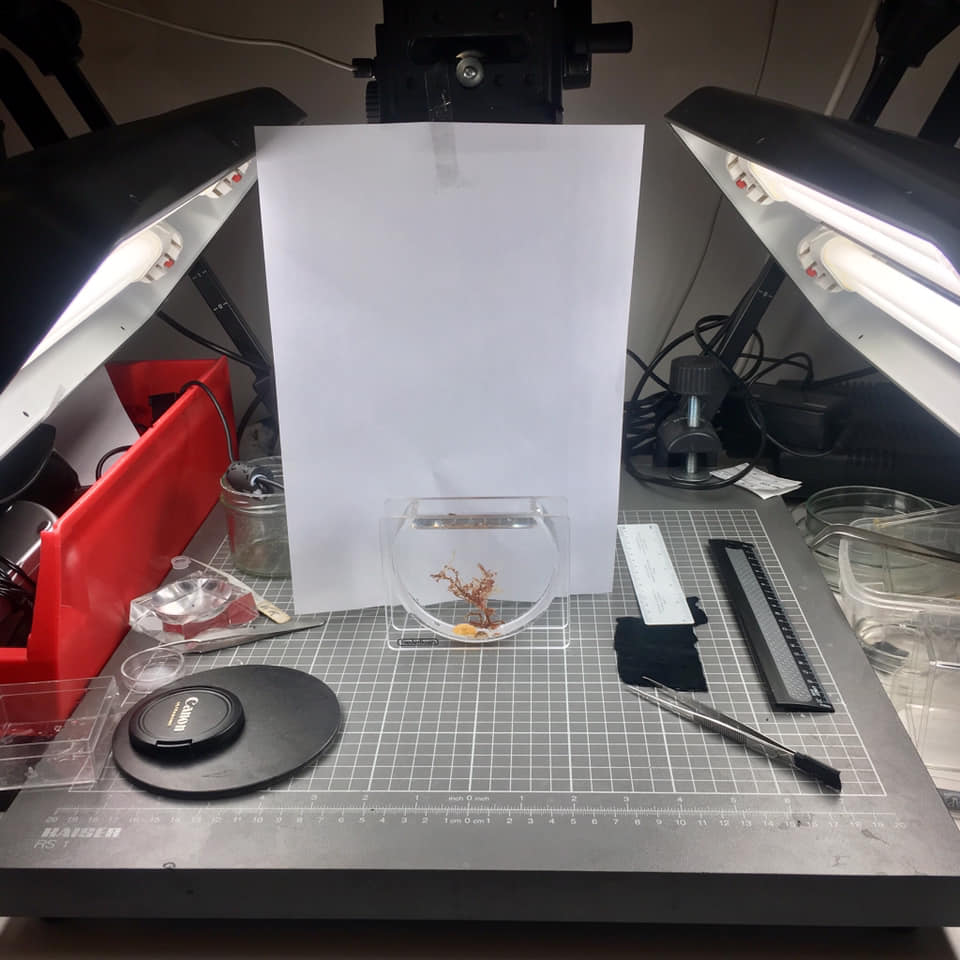

That meant more hands available to do the work, more knowledge to be shared – and definitely more fun! All projects had invited guests, mostly specialists in certain groups, but also citizen scientists, and our students participating. We stayed at the field station, which has excellent facilities for both lodging and lab work.

Participants on our Artsprojects workshop in March. Left from back: Peter Schuchert, Manuel Malaquias, Bjørn Gulliksen, Jon Kongsrud, Tom Alvestad, Gonzalo Giribet. Middle row from left: Heine Jensen, Luis Martell, Endre Willassen, Eivind Oug, Front row from left: Katrine Kongshavn, Cessa Rauch and Jenny Neuhaus (Photo: Heine Jensen)

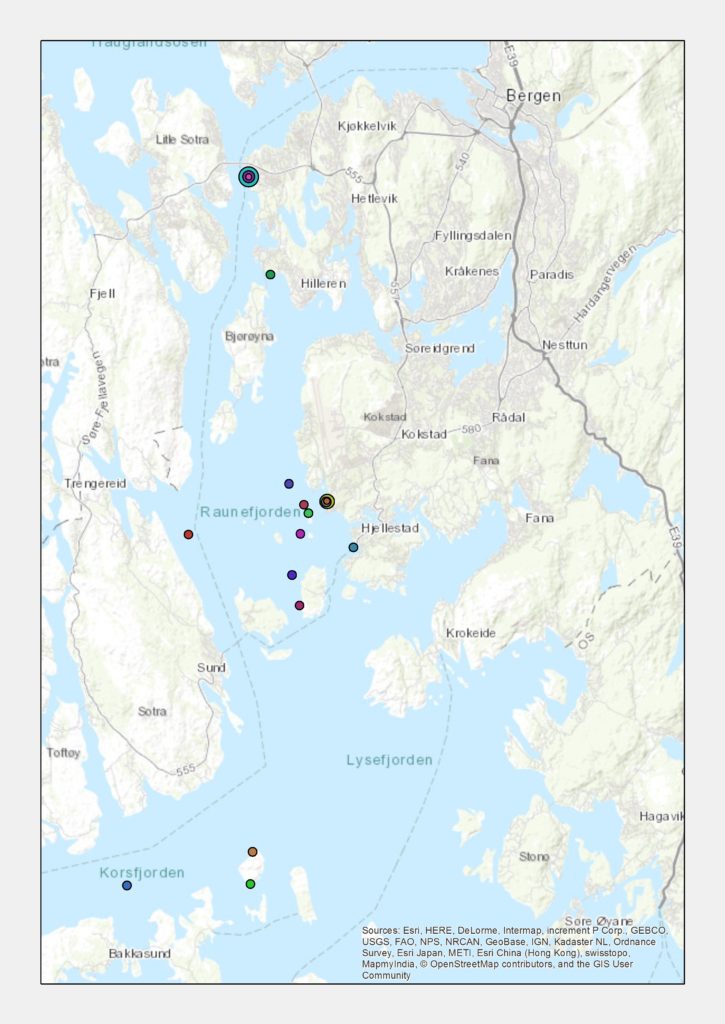

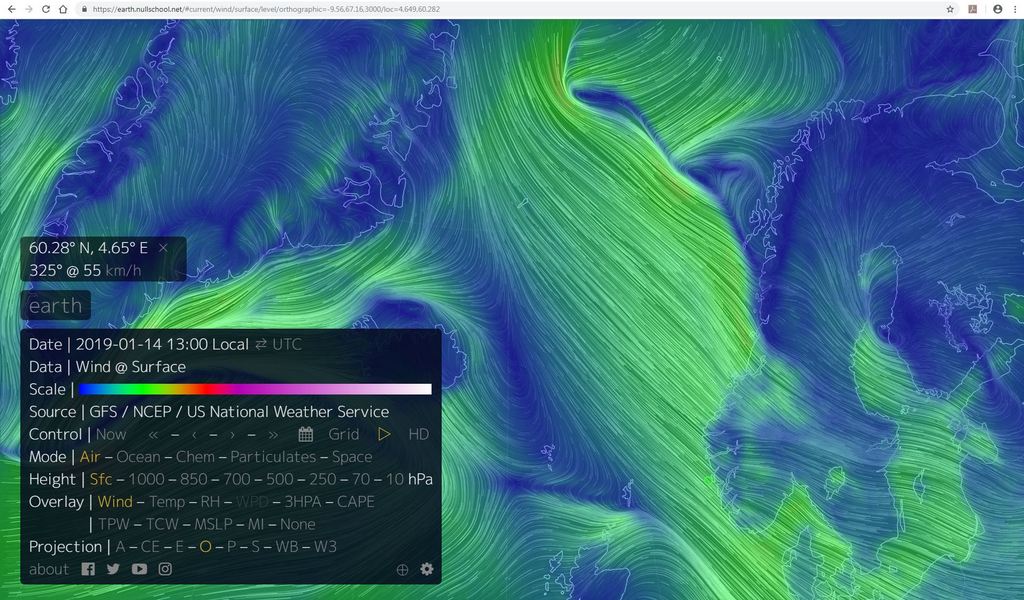

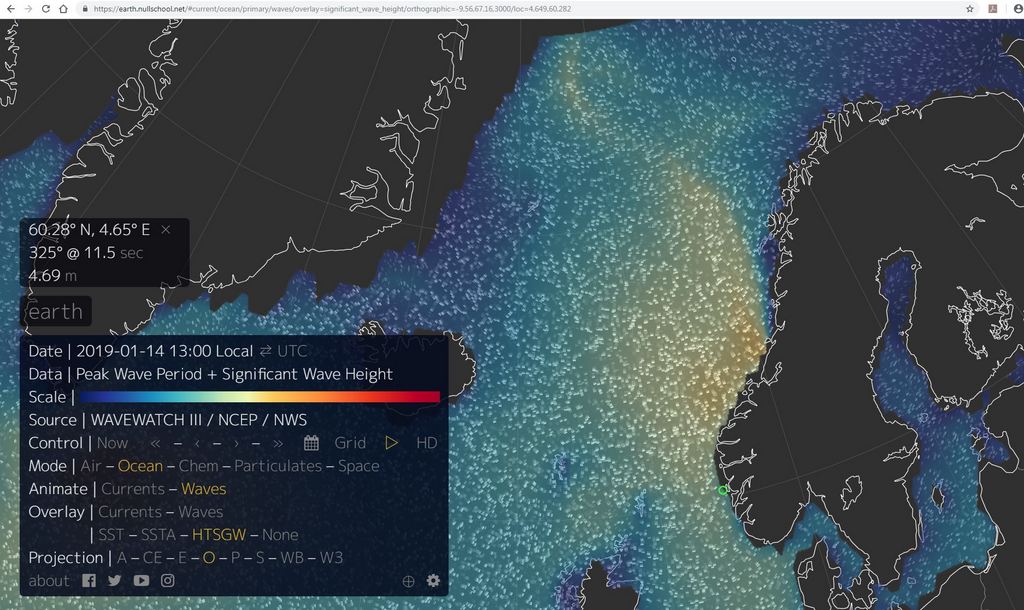

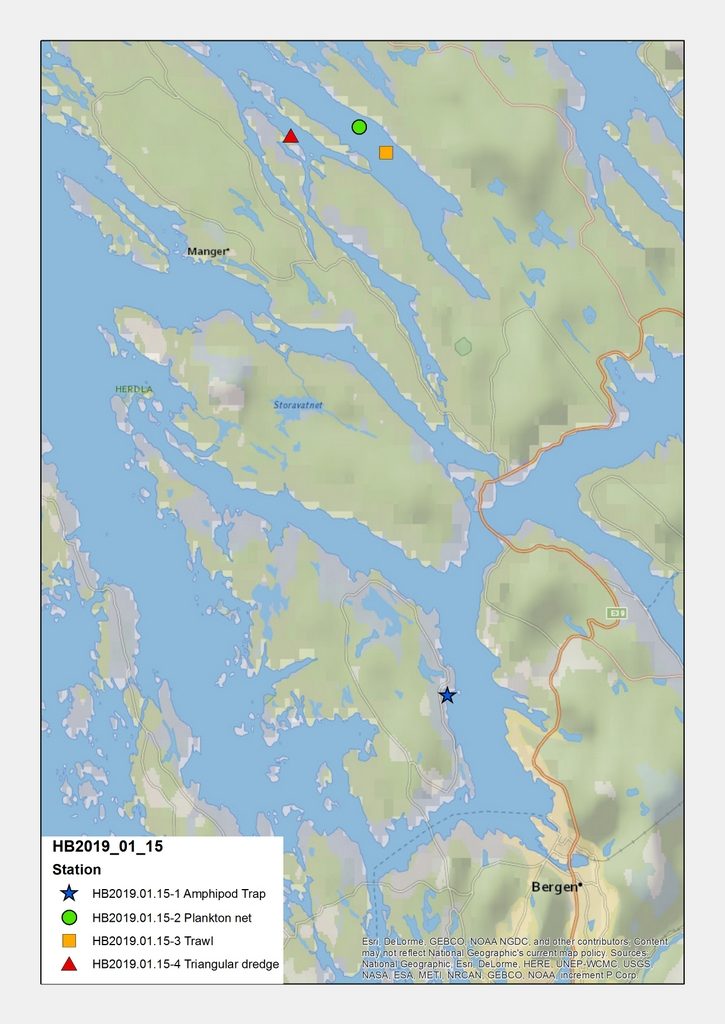

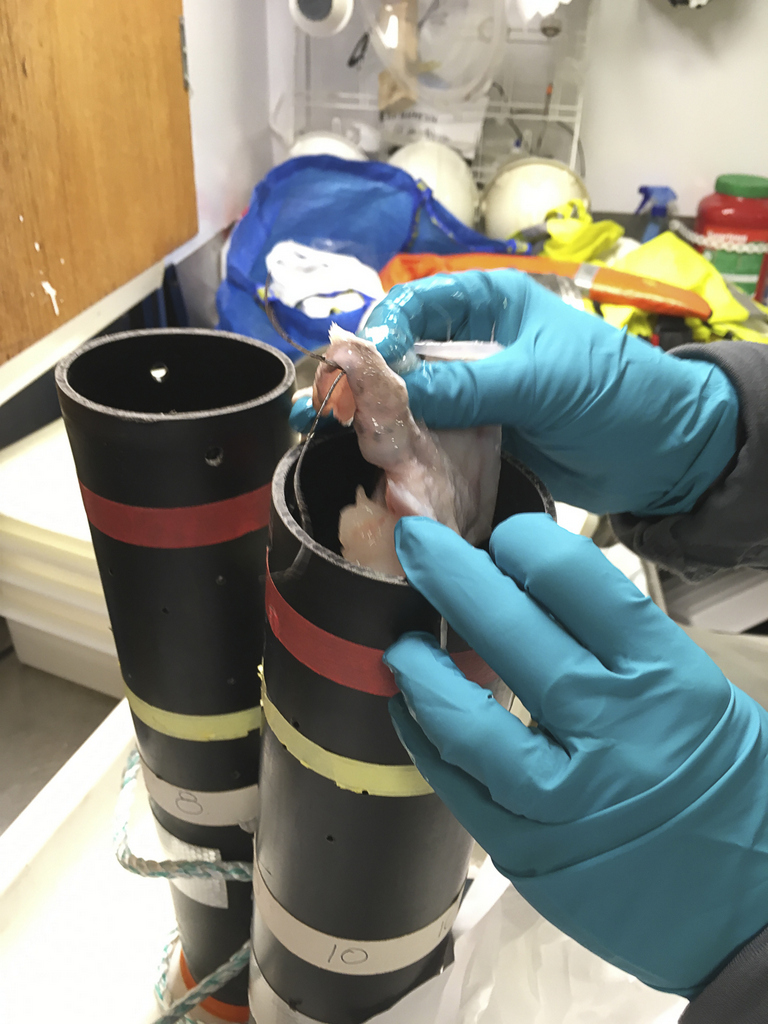

The fieldwork was carried out in the Bergen region, and was done in various ways. We had the R/V “Hans Brattstrøm” available for two days, where we were able to use triangular dredges, plankton net, and grab to sample.

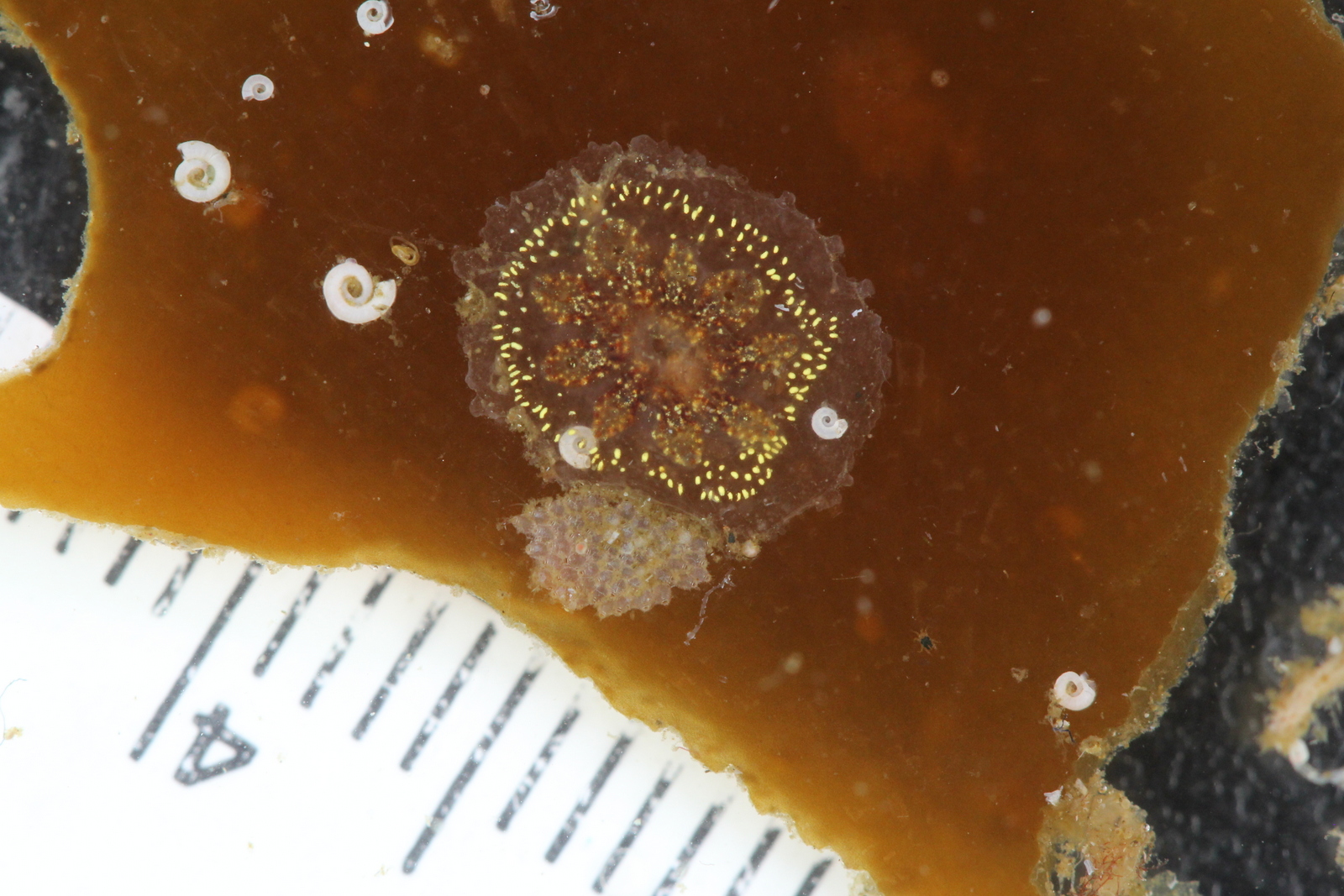

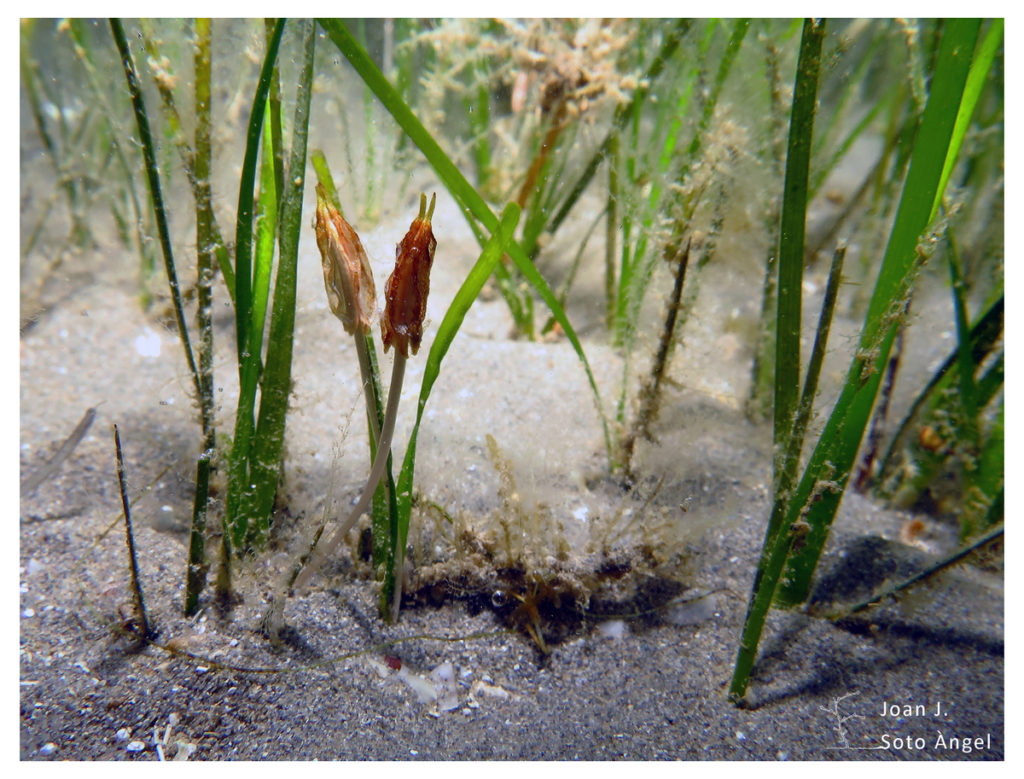

Other days we used a small boat from the station to go to the islands close to Espegrend to examine the tide pools and tidal belt. We also went to local marinas and scraped off what was living on the piers, and a brave soul donned her wet suit and went snorkeling, which enabled us to sample very specific points of interest (“take that green thing over there!”).

- R/V Hans Brattstrøm coming to pick us up (Photo: K.Kongshavn)

- This should have been filmed in slow motion with epic music in the background – we are ready to commit some serious science! ((Photo: K.Kongshavn)

- “Team Brattstrøm” on Thursday: Peter, Lina, Katrine, Luis, Cessa and Heine (front, and photographer)

- Luis waiting for the (neverending) sample of plankton at Marstein – the net needs to be pulled up very slowly so as to not damage the animals – which means a lot of waiting when it is 600 meters deep. (Photo: Heine Jensen)

- Hurray, we got the sample! It was rather wawy out at Marstein, so we were glad when we could move further into the fjords to dredge (Photo: Heine Jensen)

- A nice triangular dregde sample makes for a happy Katrine. Photo: Heine Jensen

- Endre collecting algae from just below the tide mark (photo: K. Kongshavn)

- Cessa snorkelling for sea grass whilst Manuel stands guard (photo: K.Kongshavn)

- Jon and Tom looking for ascidiacea and bryozoa on a pier (Photo: C. Rauch)

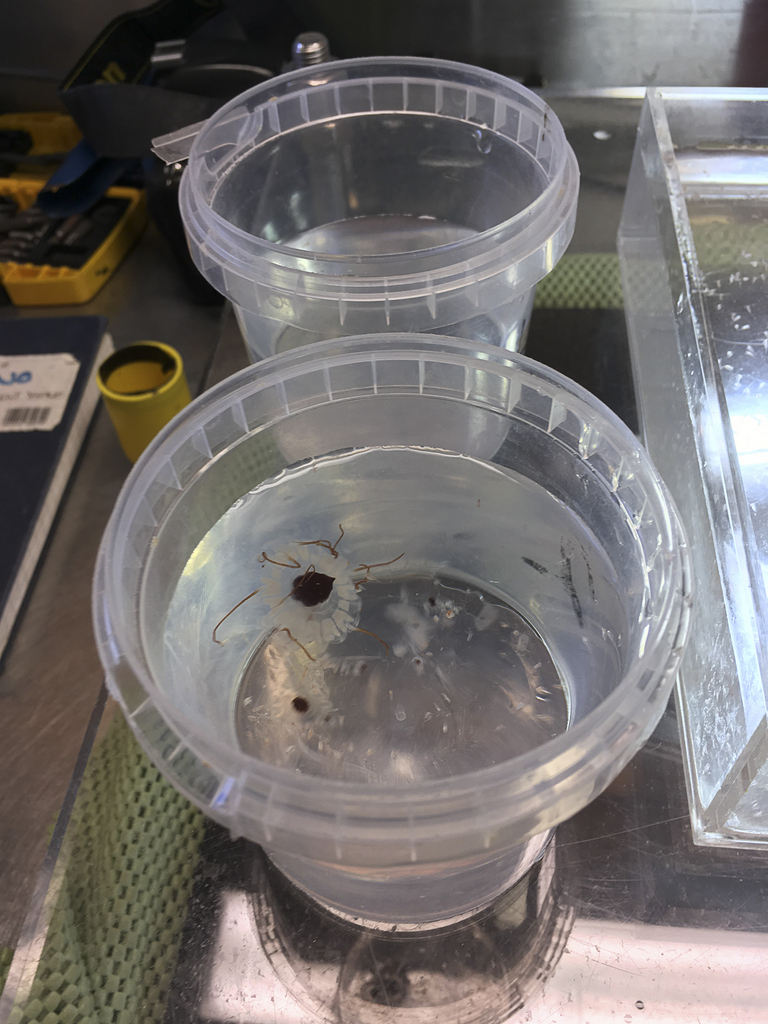

- Sorting a catch onboard R/V Hans Brattstrøm (photo: K. Kongshavn)

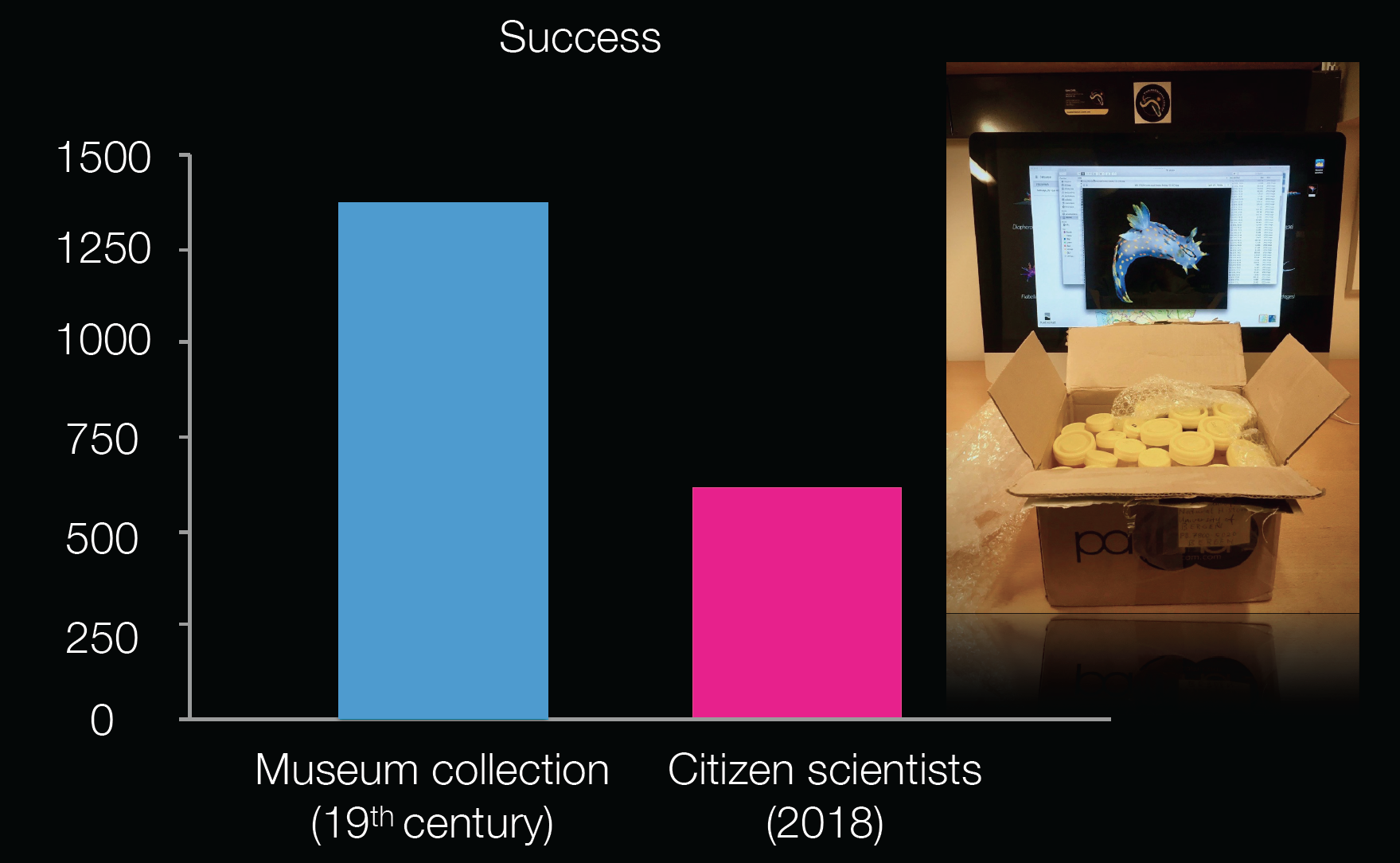

We are fortunate here in Bergen in that we have a very active local student dive club, SUB-BSI, whose divers kindly kept an eye out for – and even collected – some of our target animals, as well as sharing their photos of the animals in their natural habitat, all of which is amazing for our projects!

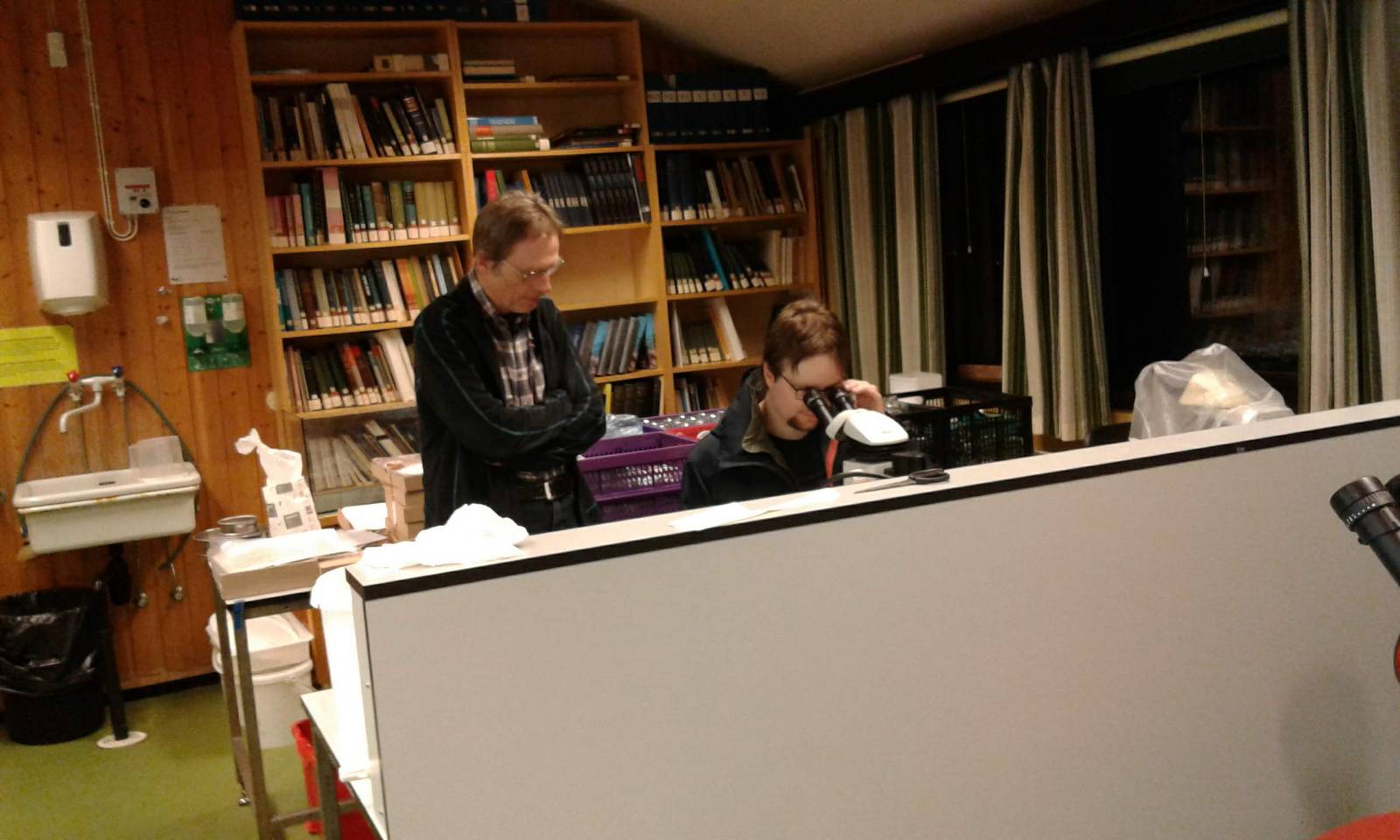

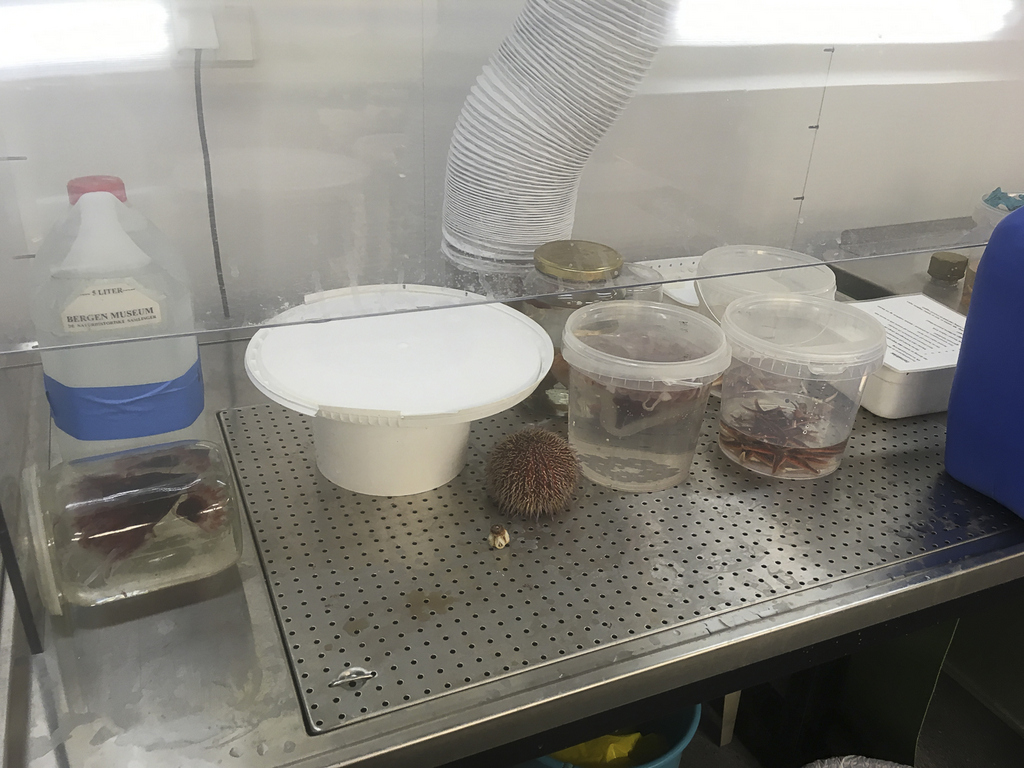

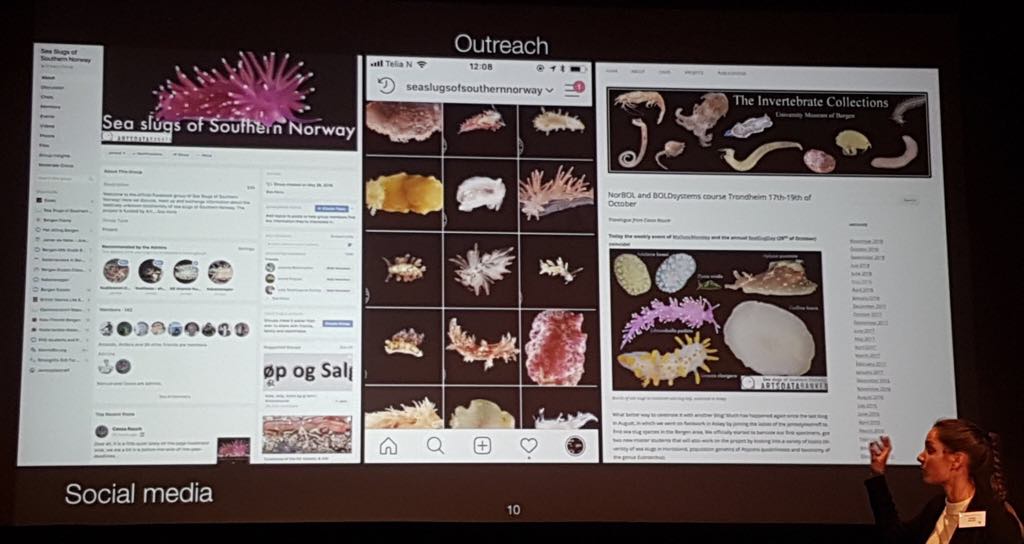

We gave short presentations of each of the projects at SUB in the beginning of the week, and invited the divers out to the lab to on the following Thursday to show some of the things we are working on. It was a very nice evening, with a lot of interested people coming out to look at our critters in the lab. We also decimated no less than 14 homemade pizzas during that evening – learning new stuff is hard work!

Guests in the lab (photos K. Kongshavn)

All together, this made it possible for us to get material from an impressive number of sites; 20 stations were sampled, and we are now working on processing the samples.

We are very grateful to all our participants and helpers for making this a productive and fun week, and we’ll make more blog posts detailing what each project found – keep an eye out for those!

You can also keep up with us on the following media:

NorHydro: Hydrozoan Science on Facebook, and Twitter #NorHydro

@Hardbunnsfauna on Instagram and Twitter

SeaSlugs: on Instagram and in the Facebookgroup

–Cessa, Luis & Katrine