R.P. sled onboard R/V. H. Brattström

Happy new year to everyone! We managed to start 2021 with a day at sea, testing the R.P. sled for collecting benthic copepods from greater depths . January 27 we went out with research vessel Hans Brattström, crew and research scientist Anne Helene Tandberg who also turns out to be a true sled expert! She would join HYPCOP to teach how to process the samples from the R.P. sled on the boat.

Anne Helene Tandberg (left) joining HYPCOP (Cessa Rauch right) for teaching how to use the sled.

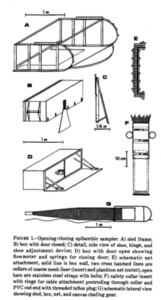

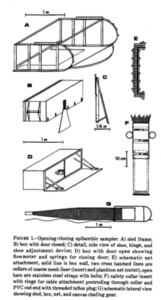

But first, what is an R.P. sled and why is it such an important key in the collection of copepods? The R.P. sled is an epibenthic sampler. That means that it samples the epibenthic animals – the animals that live just at the top of the (soft) seafloor – and a majority of these are often small crustaceans. The “R.P.” in the name stands for Rothlisherg and Pearcy who invented the sled. They needed to collect the juveniles of species of pandalid shrimp that live on the sea bottom floor. These animals are very small so a plankton net was necessary to collect them; a ‘normal’ dredge would not quite cut the job. They needed a plankton net that could be dragged over the bottom without damaging the net or the samples and also would not accidently sample the water column (pelagic); and so, the R.P. sled was born. This sled was able to go deeper than 150m, sample more than 500m3 at the time and open and close on command which was a novelty in comparison to the other sleds that where used in those days (1977). The sled consists of a steel sled like frame that contains a box that has attached to it a plankton net with an opening and closing device. The sled is heavy, ca. 150kg, and therefore limits the vessel sizes that can operate it; the trawl needs to be appropriately equipped including knowledgeable crew. It is pulled behind the vessel at slow speed to make sure the animals are not damaged and to make sure it does not become too full of sediment that is whirled up.

-

-

Original drawings of R.P. sled by Rothlisherg and Pearcy 1977

-

-

The R.P. sled in modern days with H. Brattström crew member for scale

Sieved animals from the decanting process

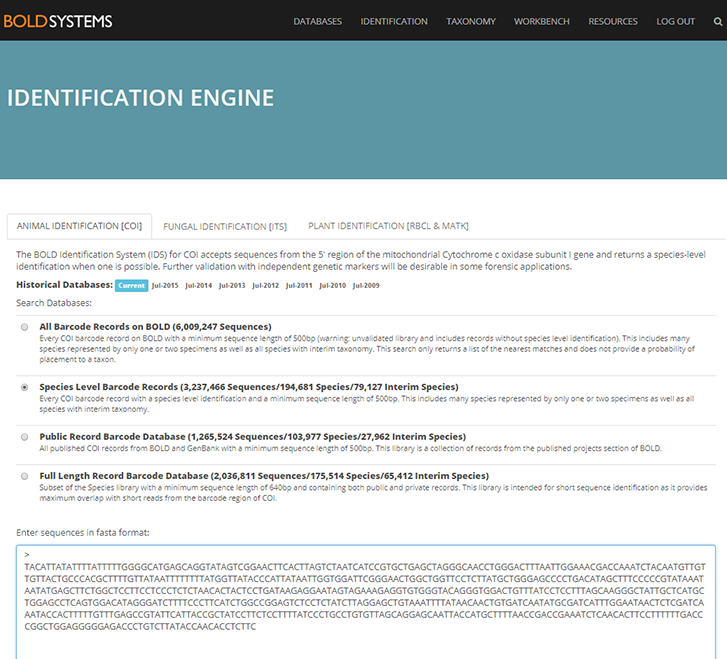

So off we went with r/v Hans Brattström pulling the heavy gear at ca. 700m depth with 1 knot and a bottom time of 10 minutes sampling the Krossfjorden close to Bergen. It was a beautiful day for it with plenty of sun and calm seas. The crew handled most of the sled, leaving sorting the samples up to HYPCOP under the guidance of Anne Helene. Which is not as straight forward as it may sound! The process of filtering the samples after collecting them from the sled is done by decanting, which you can see in this movie from an this blog (in Norwegian) from earlier.

Decanting set-up for R.P. sled samples

Decanting means separating the mixture of the animal soup from the liquid by washing them in a big bucket, throw the liquid through a filter and collect the animals.

Sieved animals from the decanting process

This all needs to be done with care as the animals are often very small and fragile. After collecting, the most time-efficient and best preservation for the samples is to fixate them immediately with ethanol, so they don’t go bad while traveling back to the museum.

Fixating collected animals with technical ethanol

For collecting copepods we use a variety of methods; from snorkeling, to scoping up water and plankton nets, but for greater depths and great quality benthic samples the R.P. sled will be the most important method. We thank Anne Helene for her wisdom and enthusiasm that day for showing HYPCOP how to work with such interesting sampling method

-

-

Anne Helene (left) and HYPCOP (Cessa right) posing with the catch of the day

-

-

Anne Helene (right) using her sled wisdom for fixing the cod-end with H. Brattstrøm crew (left)

We got some nice samples that will be sequenced very soon so we can label them appropriately. Although this first fieldwork trip off the year was mainly a teaching opportunity, we still managed to sample two stations with plenty of copepods and lots of other nice epibenthic crustacea, and Anne Helene is especially happy with all the amphipods she collected during the day. So for both of the scientists aboard this was a wonderful day – sunshine and lovely samples to bring back to the lab!

Some fresh copepods caught with the R.P. sled

– Cessa & Anne Helene

Follow HYPCOP @planetcopepod Instagram, for pretty copepod pictures https://www.instagram.com/planetcopepod/

Twitter, for copepod science news https://twitter.com/planetcopepod

Facebook, for copepod discussions https://www.facebook.com/groups/planetcopepod

See you there!