NorHydro partner (and hydrozoan expert) Joan J. Soto Àngel from the Sars International Centre for Marine Molecular Biology went in a sampling trip to Kinn to collect benthic hydroids. Here is an account of his experience in this trip:

Kinn is a small grassy island on the western Norwegian coast. Today it is a quiet, peaceful place with only a few inhabitants, but in the past it was an important fishing town and the center of the cultural and religious life of the area, as evidenced by its imposing medieval stone church (Kinnakyrkja). The island is also a place of historical relevance for biologists, since it is intimately tied to the life and discoveries of one of the most prominent naturalists of the XIX century, Michael Sars, who worked as a priest in Kinnakyrkja for many years.

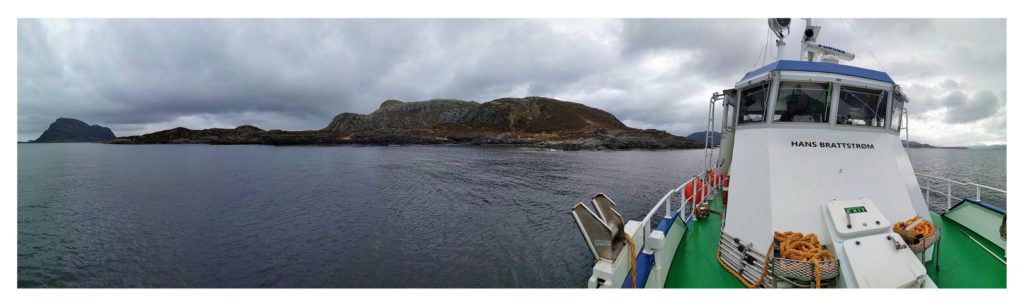

Here I am, ready to sample! The island behind is Kinn, easy to recognize thanks to its characteristic cleft silhouette. Picture: Cessa Rauch

The islands in the area face the ocean and are rather exposed, so the vegetation is not particularly tall, but the waters are teeming with life. Picture: Joan J. Soto

Sars described many species inhabiting the waters around Kinn and also made key observations about their distribution and life cycle. Indeed, he was the first to discover that jellyfish and polyps are in fact different stages of the same animals!

This finding led him to be recognized as an outstanding zoologist of his time. Even now, ca 200 years after, his extensive work is regularly consulted by researchers of many fields. Like me and the other participants of the Artsdatabanken project NorHydro, Sars was fascinated by the group we call Hydrozoa, which is why it was very interesting for our project to join a sampling trip of the University Museum of Bergen in the same waters where he sampled and described many hydroids, hydromedusae and siphonophores.

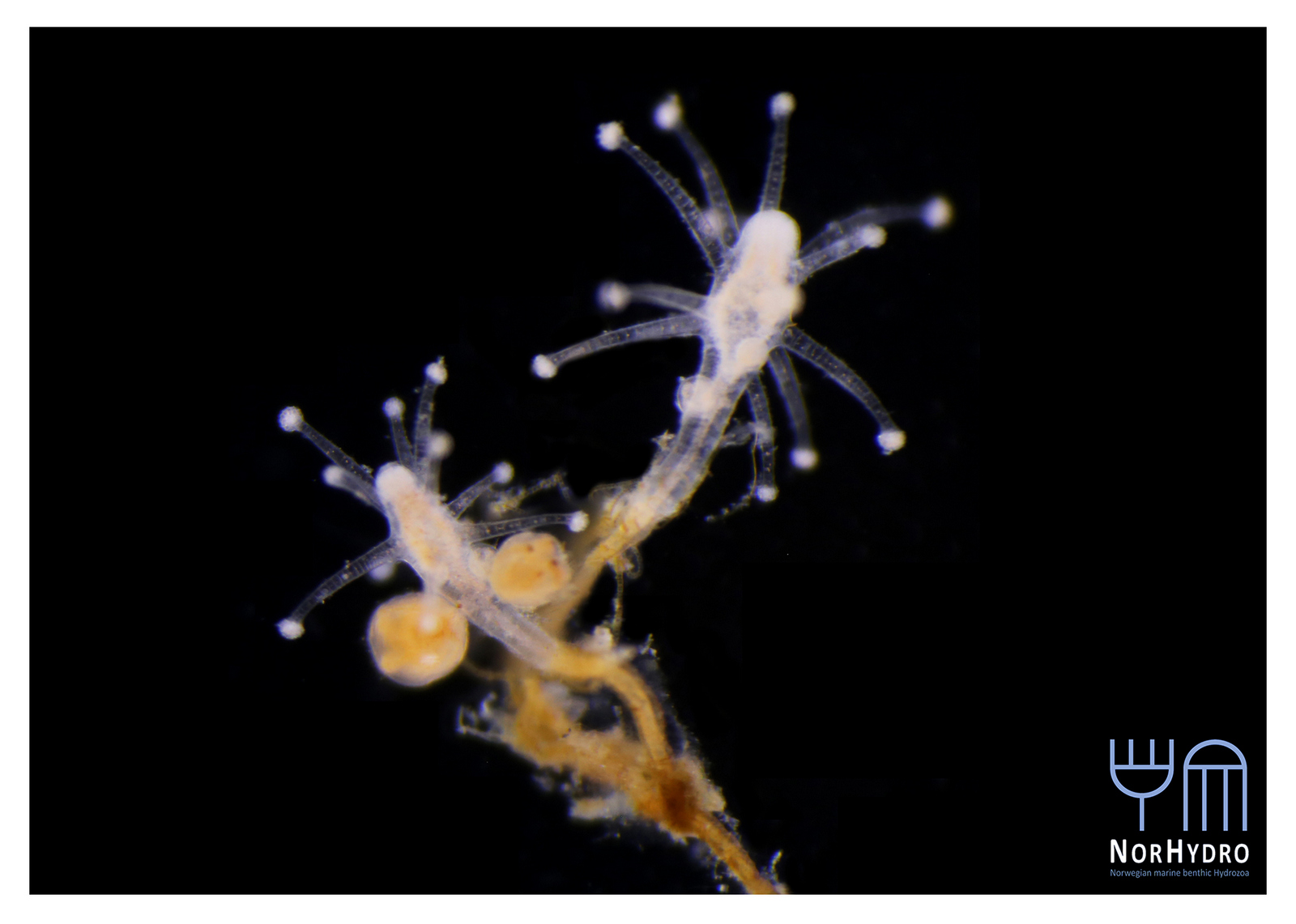

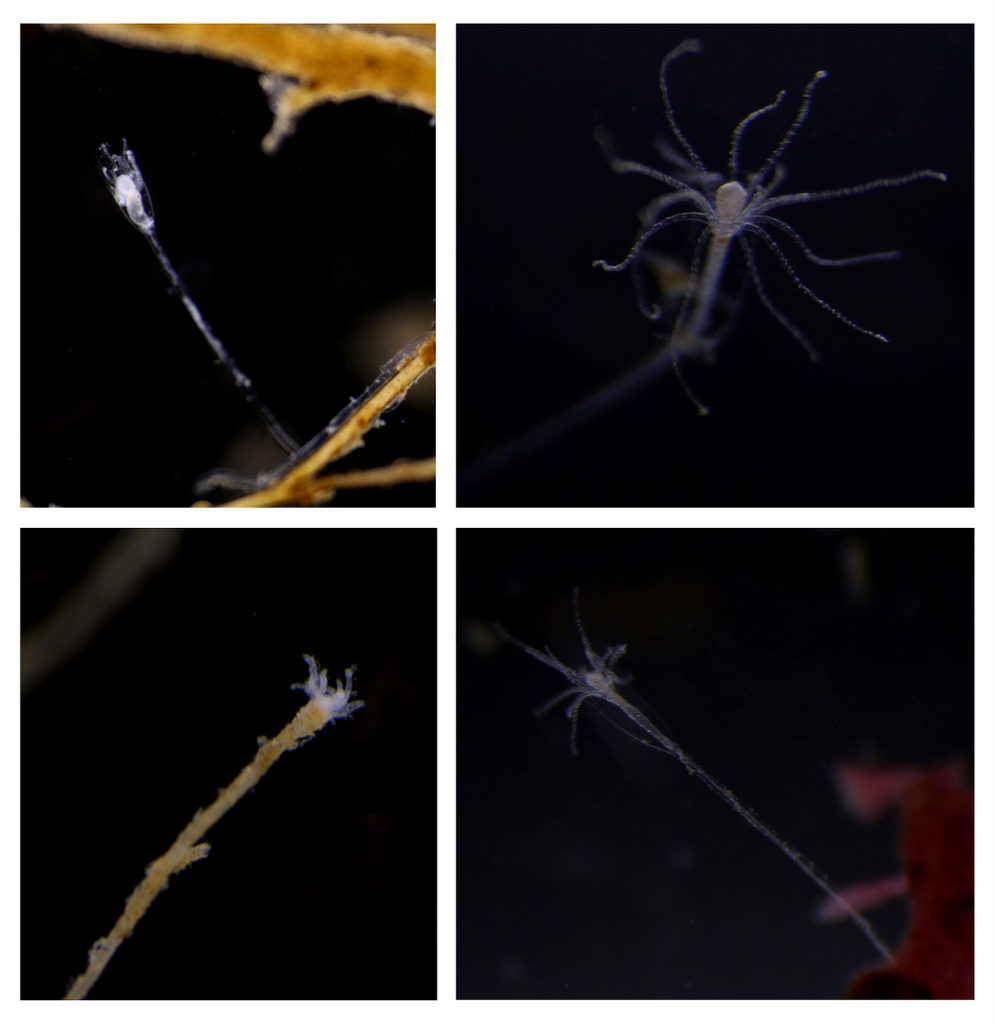

- Michael Sars contributed so much to hydrozoan science that is not surprising that several species names have been dedicated to him. Perhaps one of the most famous is genus Sarsia, here represented by Sarsia tubulosa, a species described by him in 1835. He worked with both the polyp and medusa stages. Pictures: Luis Martell (polyp), Elena Degtyareva (jellyfish).

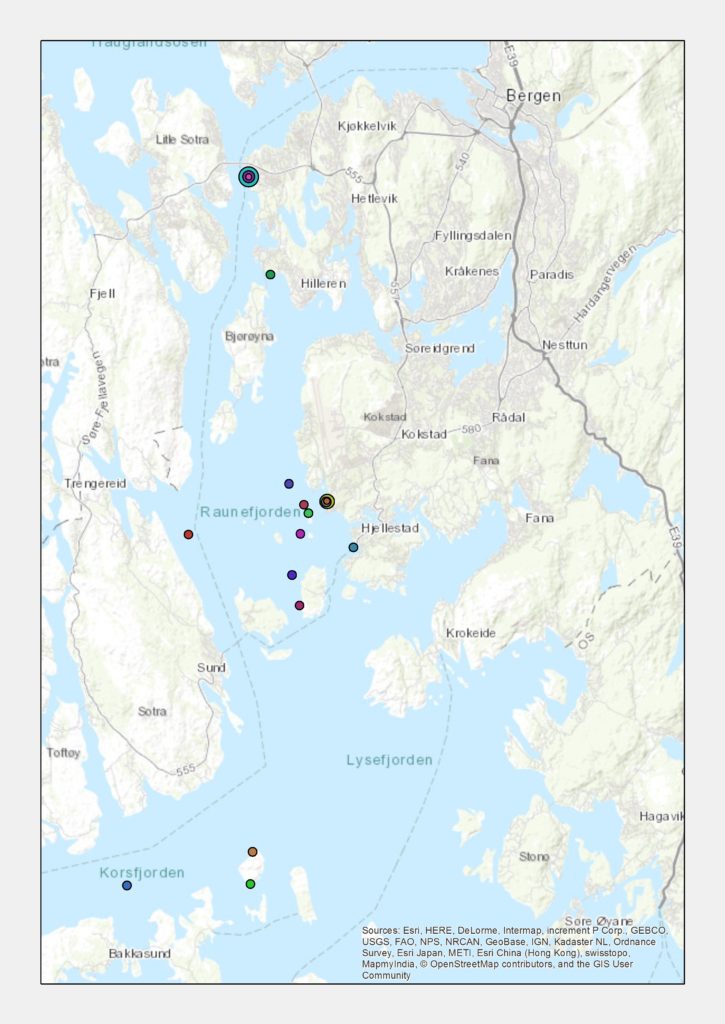

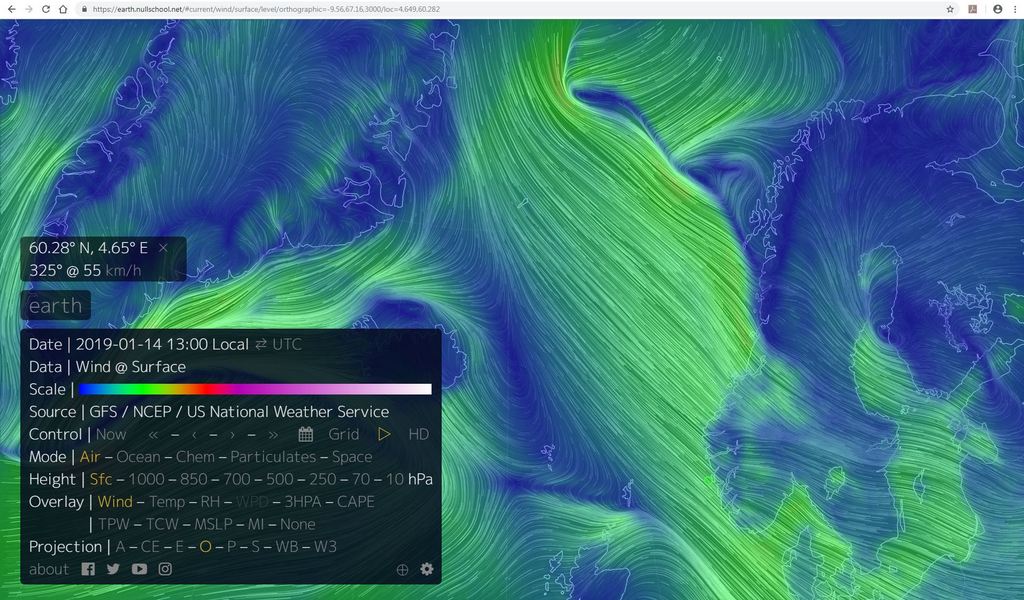

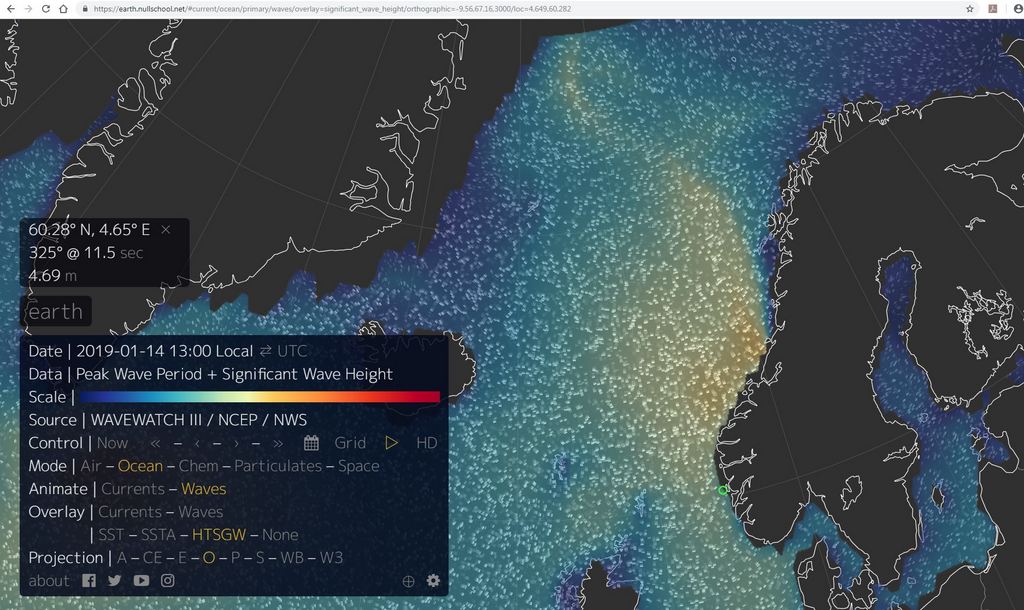

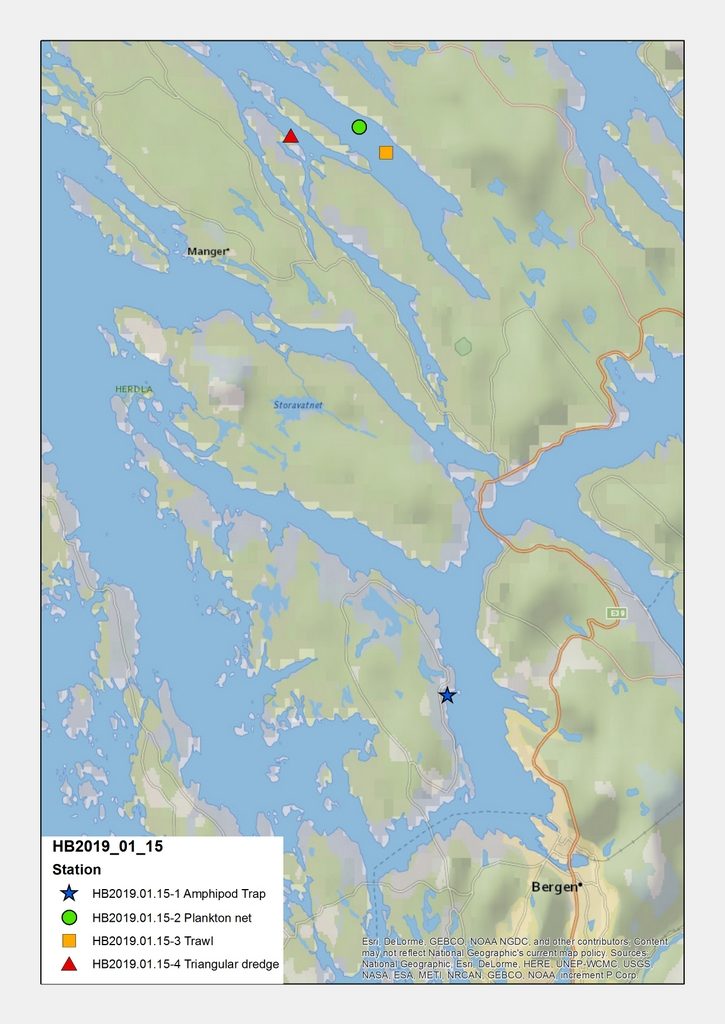

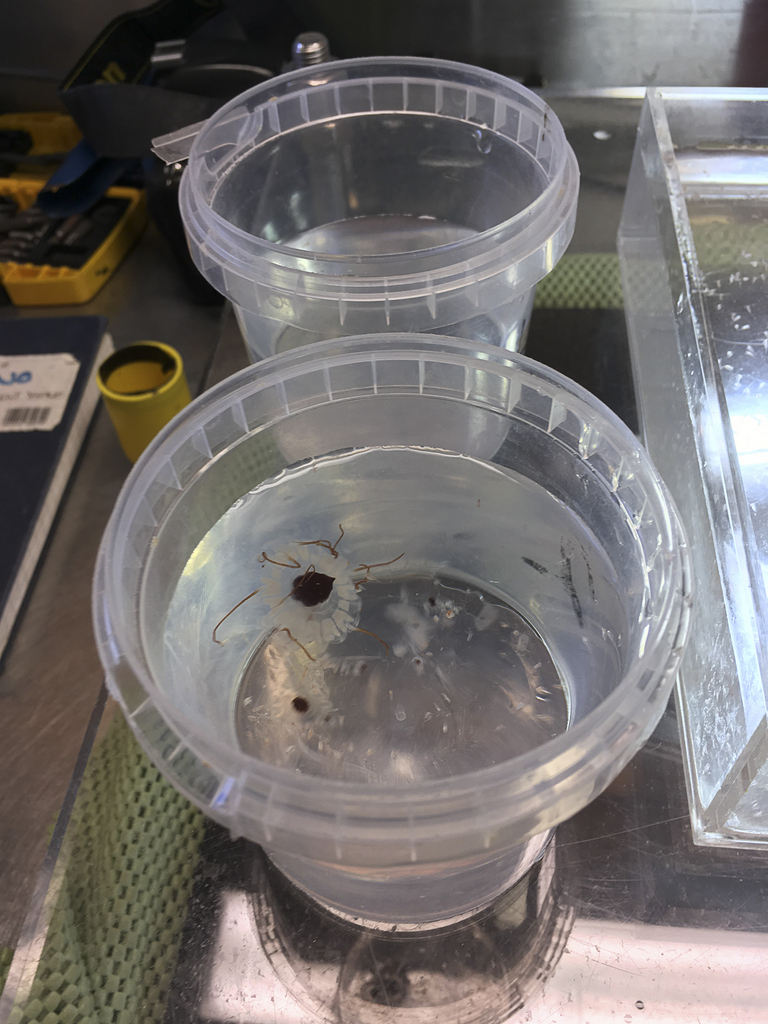

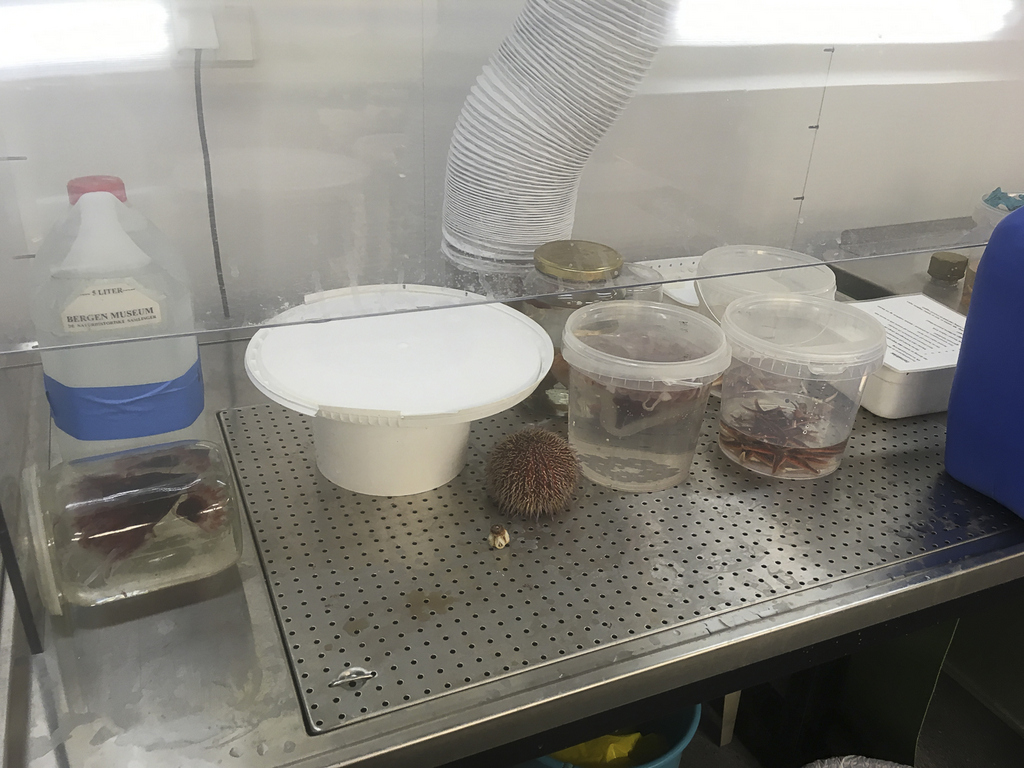

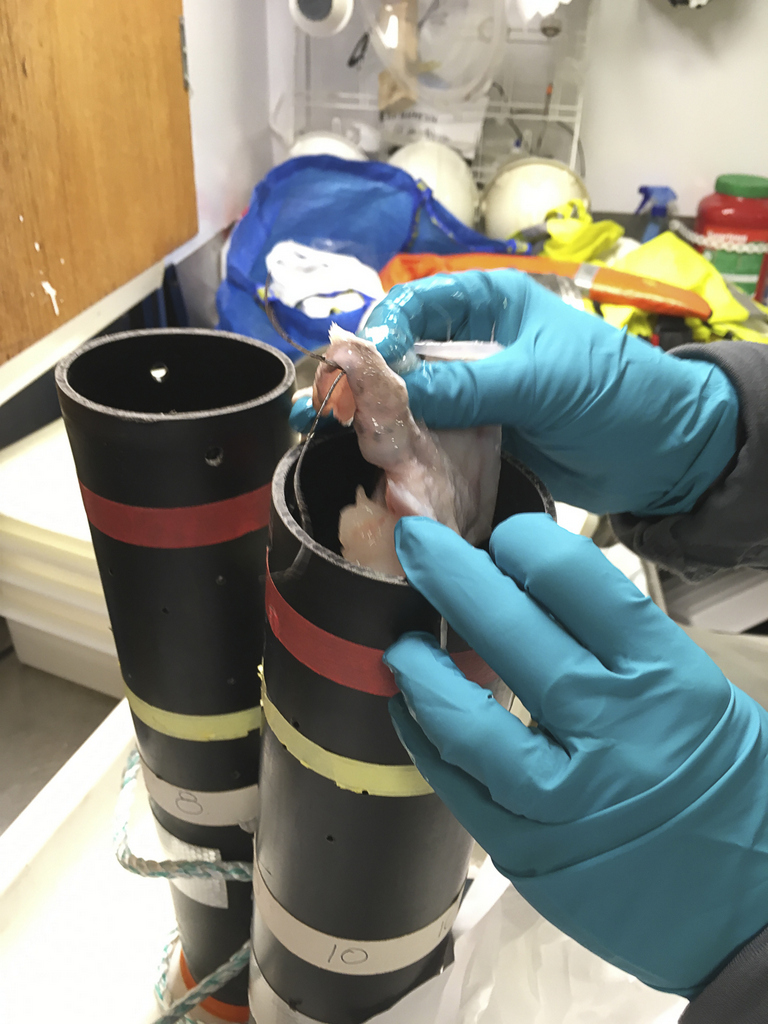

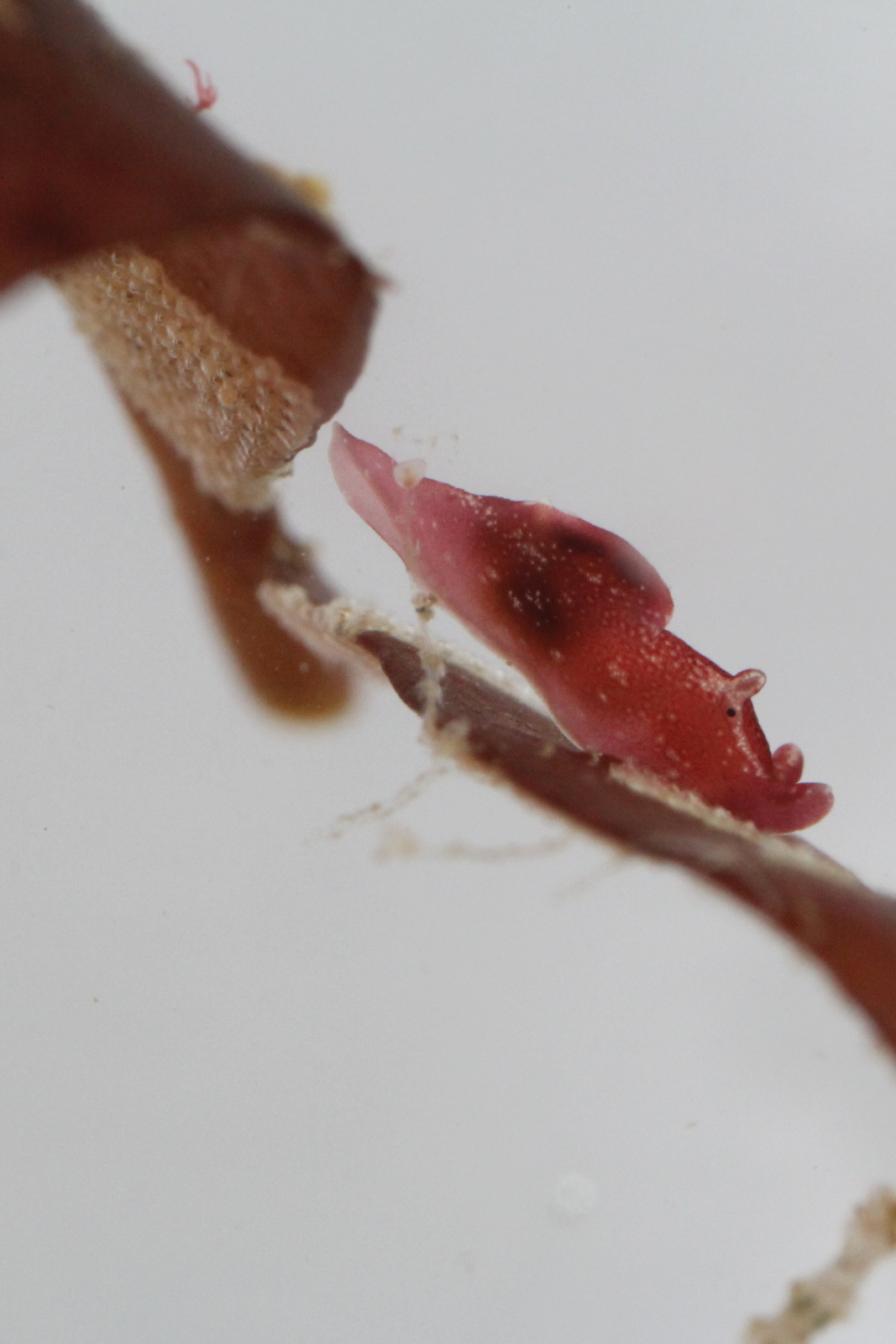

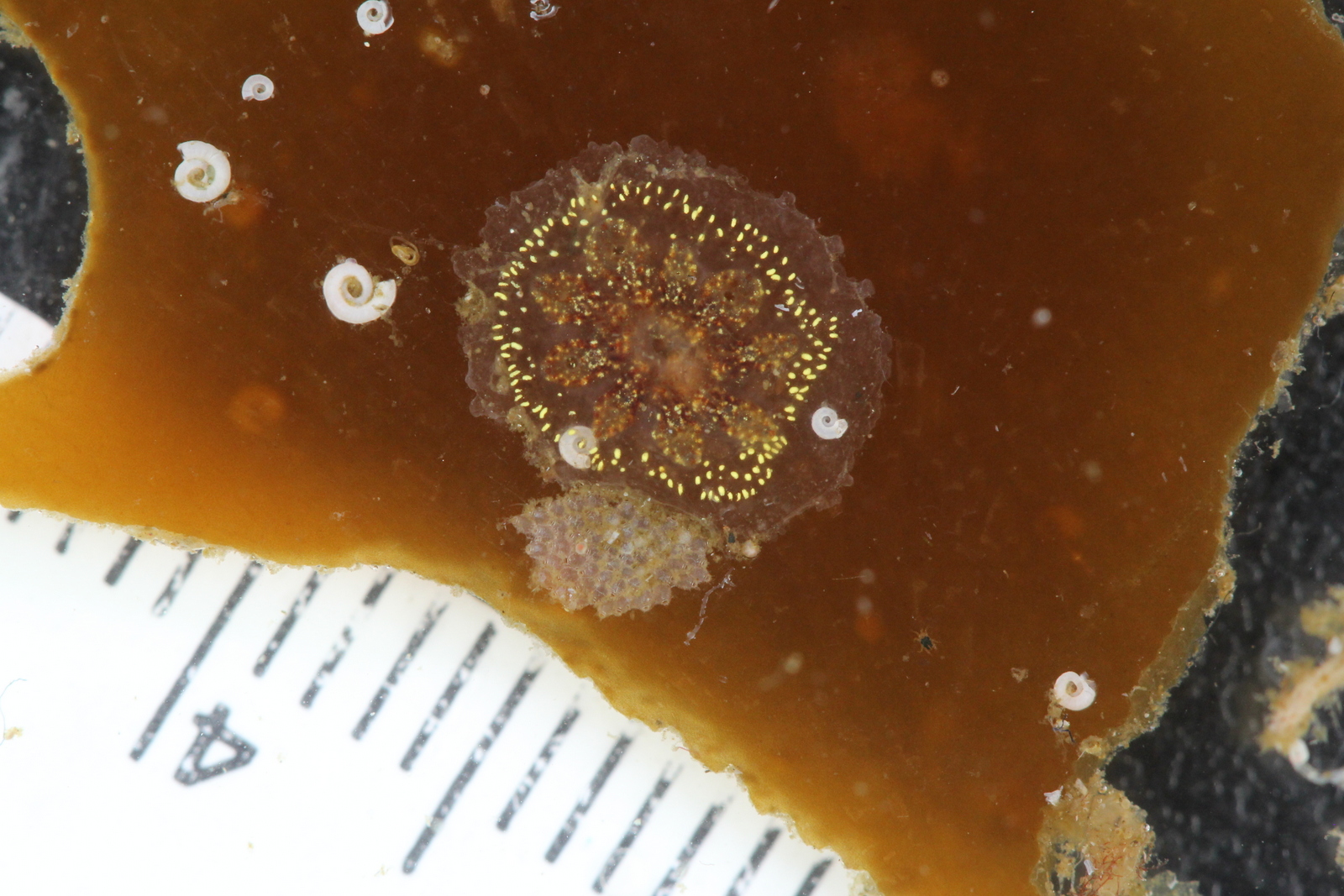

Because Sars was also interested in other critters of the sea besides hydrozoans, it was only natural to make this sampling trip a joint, collaborative effort. In our case, three marine scientists were involved, each representing a different project: I was in charge of the hydrozoans for NorHydro, while Anne Helene Solberg Tandberg focused on amphipods (NorAmph2) and Cessa Rauch concentrated on sea slugs (Sea Slugs of Southern Norway). But we did not limit ourselves to our favorite animal groups; we also sampled some poychaetes, bryozoans, ascidians and echinoderms for two other projects based at UMB, Hardbunnsfauna and AnDeepNor. In addition, while we sampled extensively the waters around Kinn, we also stopped in the way to the island and back and collected some animals in two other localities in the coast of Sogn og Fjordane. Our efforts paid off and, despite some windy weather, we came home with many specimens to analyze and samples to sort.

Three more contemporary naturalists working for different projects: Joan (left, NorHydro), Cessa (middle, Sea Slugs of Southern Norway), and Anne Helene (right, NorAmph2). Picture: Joan J. Soto

- The Norwegian coast between Bergen and Kinn is full of islands and fjords that offer many opportunities for hydroids to grow.

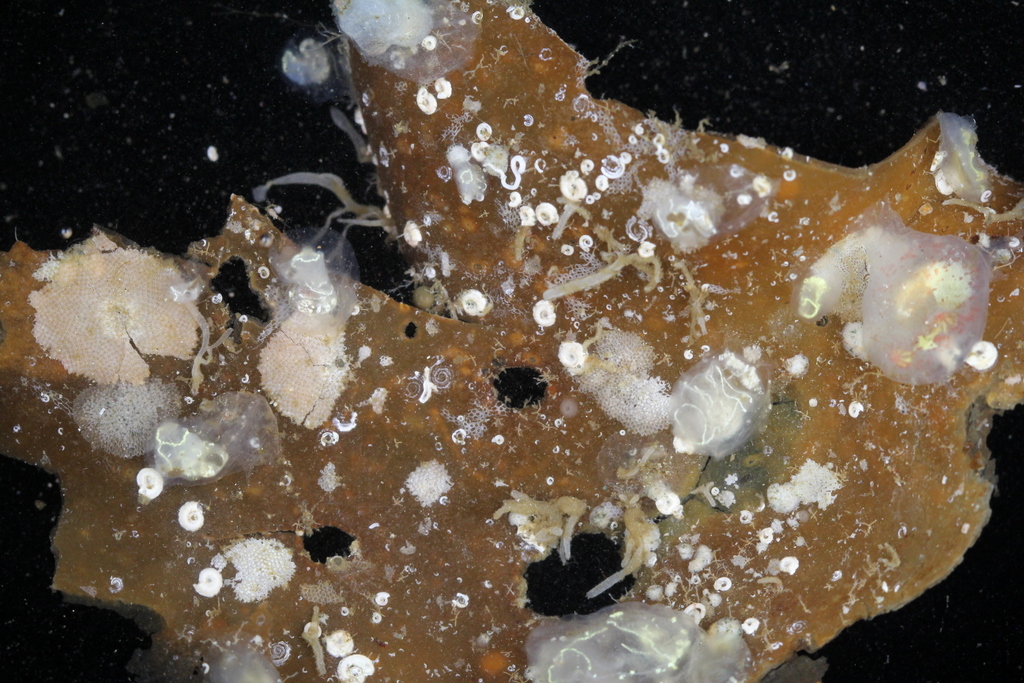

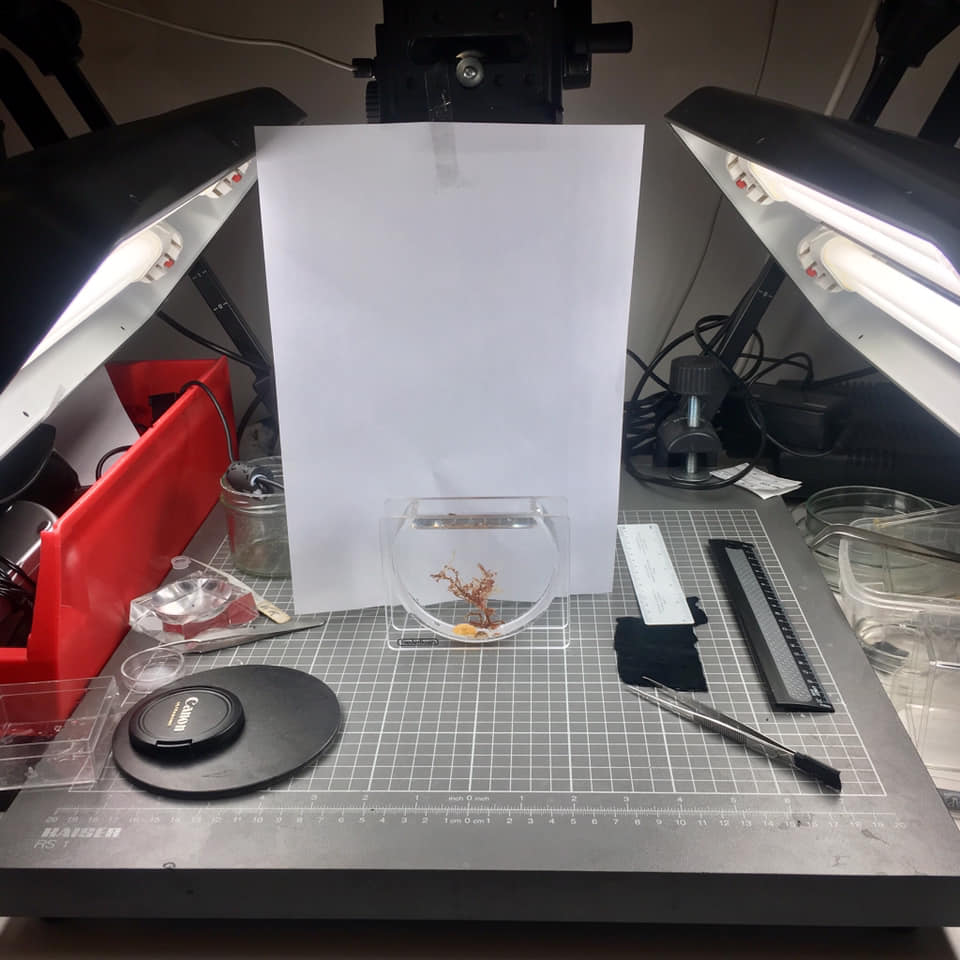

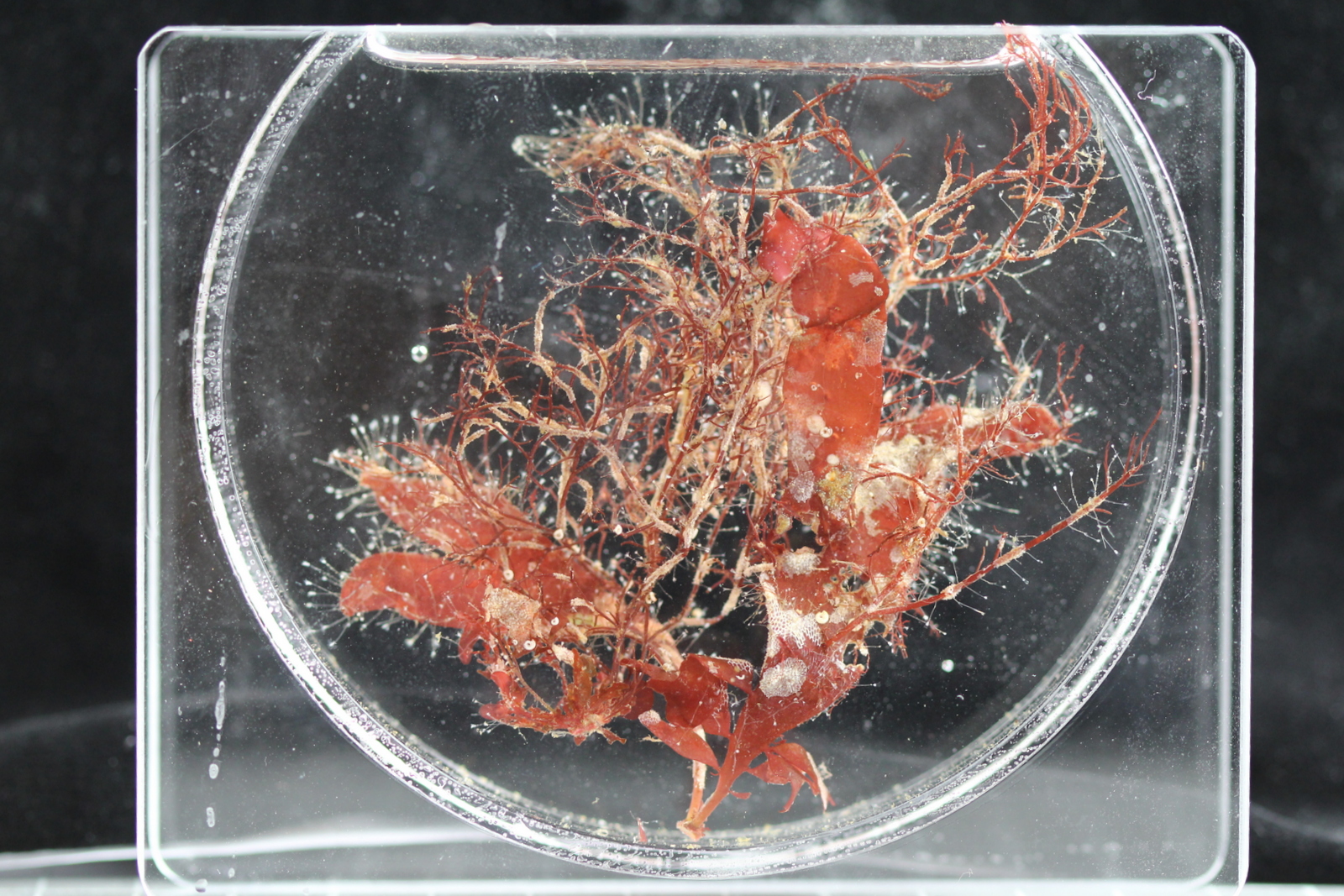

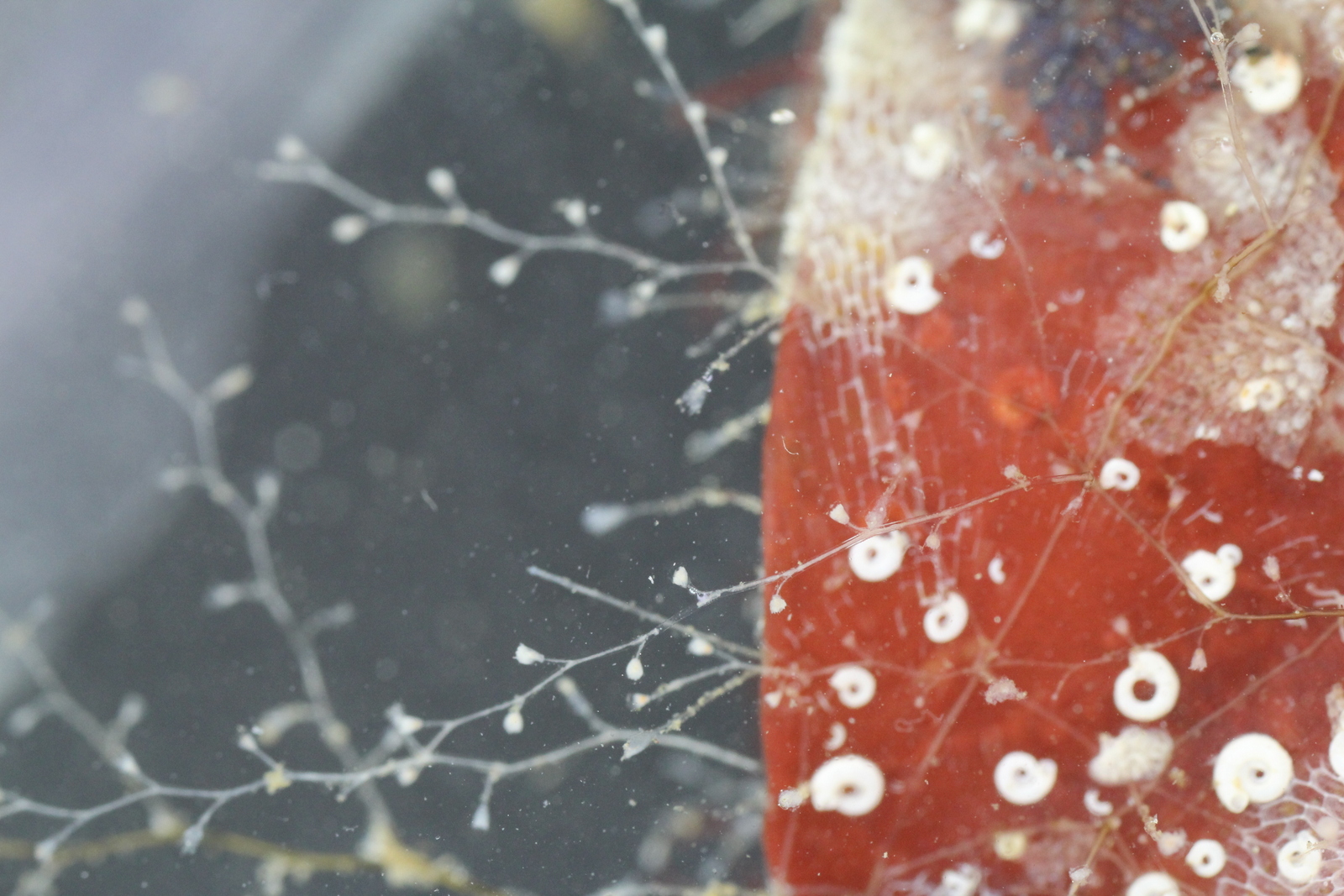

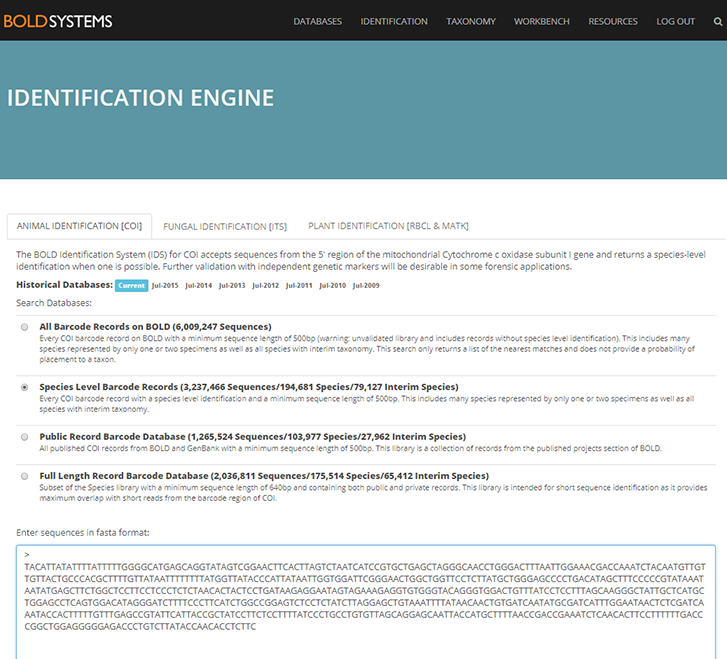

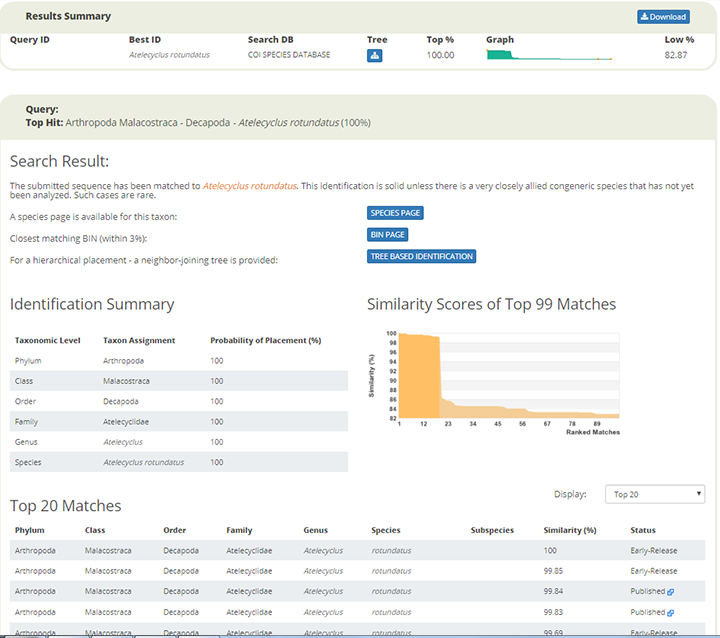

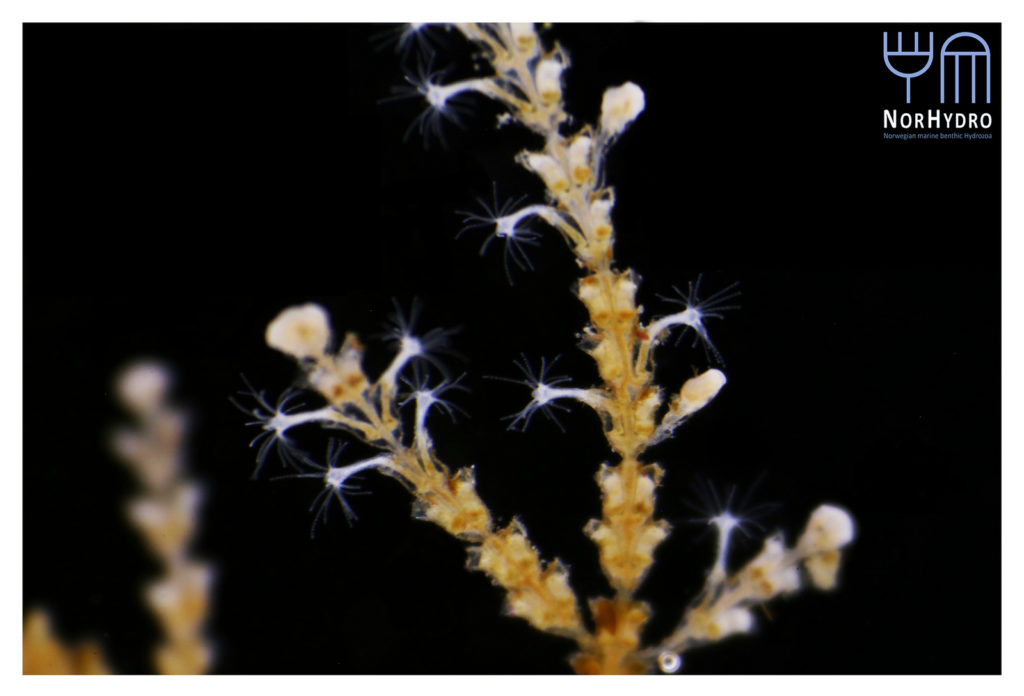

For the hydrozoans, the majority of samples consisted in colonies of hydroids belonging to the families Sertulariidae, Haleciidae and Campanulariidae. This was not surprising as Sertulariidae (sensu lato) is the largest and most diverse family in all Hydrozoa, and their conspicuous colonies are relatively easy to recognize and collect. The haleciids are represented in Norway mainly by species of Halecium, whose colonies are among the largest benthic hydrozoans of the country. As for the campanulariids, particularly those belonging to genera Obelia, Laomedea and Clytia, they are common inhabitants of rocky and mixed bottoms all around the world, and are especially conspicuous when growing on macroalgae such as kelp. To correctly identify some of these specimens, we will look closely at their morphological characteristics and will also employ molecular techniques of DNA analysis. Hopefully this approach will help us understand the diversity of benthic hydroids living around Kinn, and will allow us to determine whether the species that we encountered are the same that Sars studied.

Dynamena pumila was one of the most conspicuous species of hydroid that we collected in this trip. It belongs to the speciose family Sertulariidae.

We were very lucky to have the help of the crew of RV Hans Brattström. This is how the command center of the boat looks like!

You’ll find the results of these and other NorHydro’s analyses here in the blog as we progress, and more updates on the project can be found on the Hydrozoan Science facebook page and in Twitter with the hashtag #NorHydro.

– Joan

References and related literature about Michael Sars

Tandberg AHS, L Martell (2018) En uimodstaaelig lyst til naturens studium. Yearbook of the University Museum of Bergen: 17 – 26.

Sars M (1835) Beskrivelser og Iagttagelser over nogle mærkelige eller nye i Havet ved den Bergenske Kyst levende Dyr af polypernes, acalephernes, radiaternes, annelidernes, og molluskernes classer. Thorstein Hallagers forlag, Bergen.

Windsor MP (1976) Starfish, jellyfish and the order of life. Issues in Nineteenth-Century Science. Yale University Press, New Haven. 228 pp