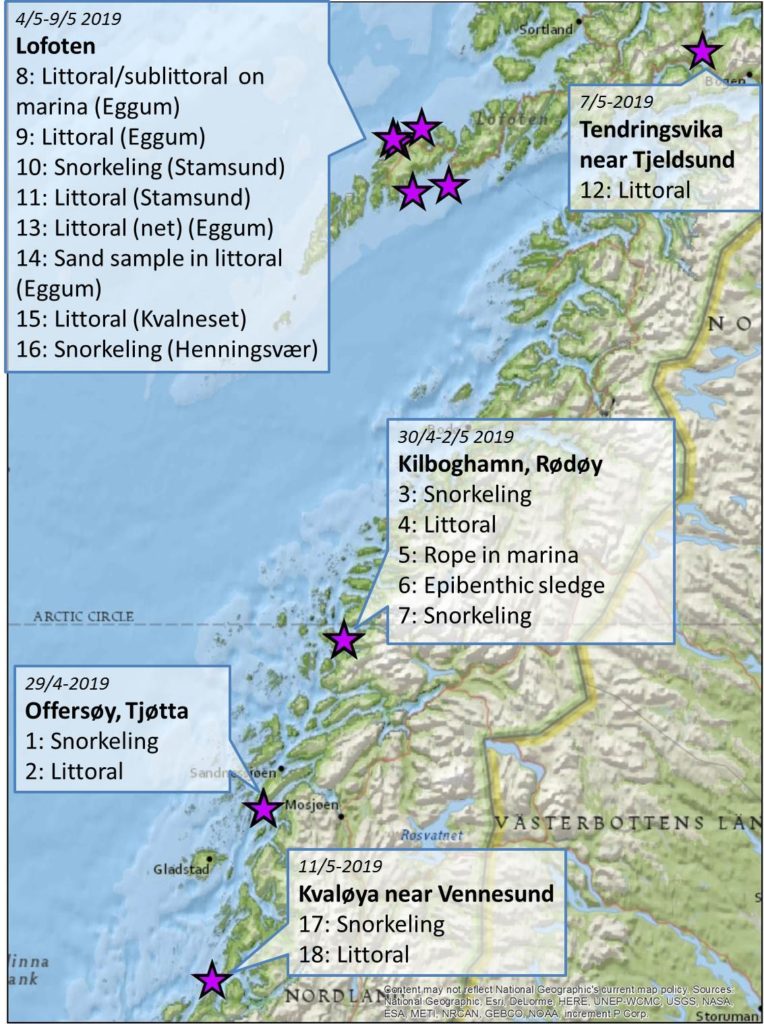

2019 will bring a lot of field work for us at the invertebrate collections – not only do we have our usual activity, but we will also have *FIVE* Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative projects (Artsprosjekt) running!

On a rather windy Tuesday in January, four of us – representing four of these projects – set out with R/V “Hans Brattstrøm”.

Four projects on the hunt for samples! Photo: A.H.S. Tandberg

-

-

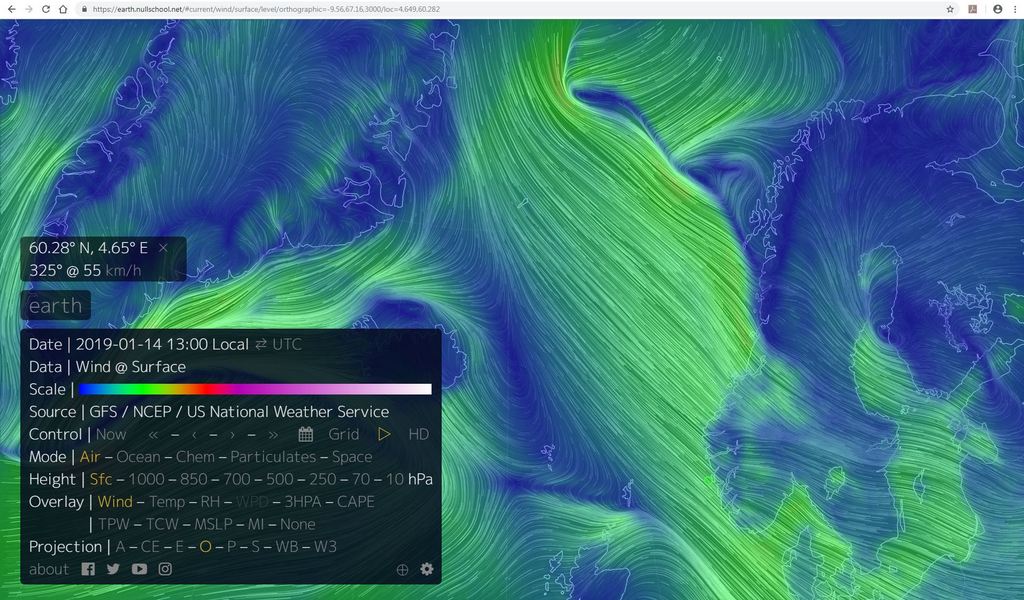

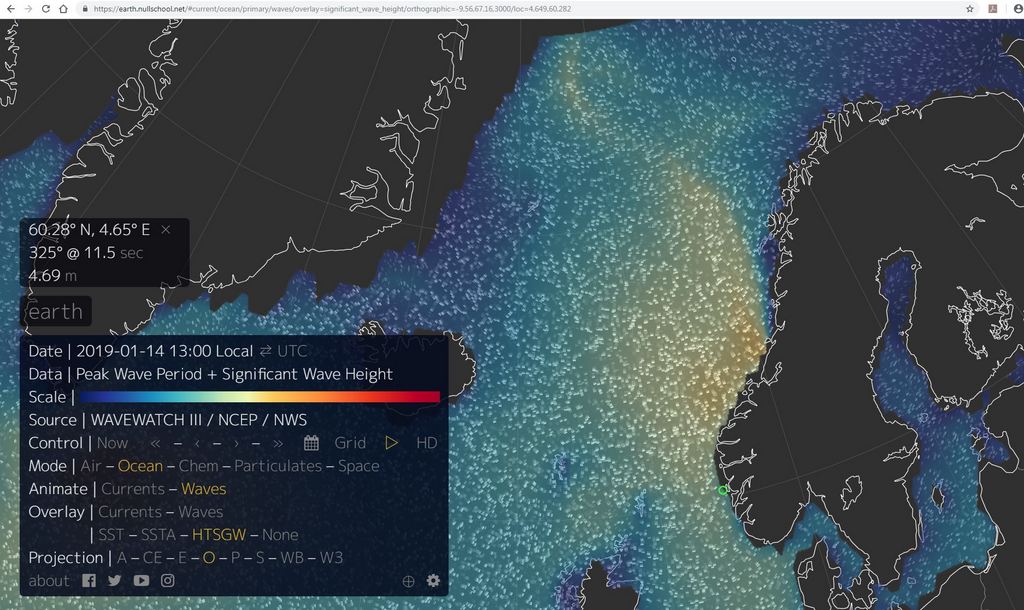

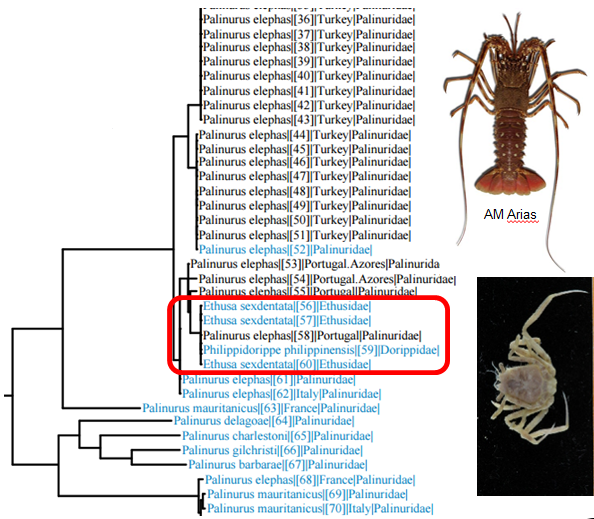

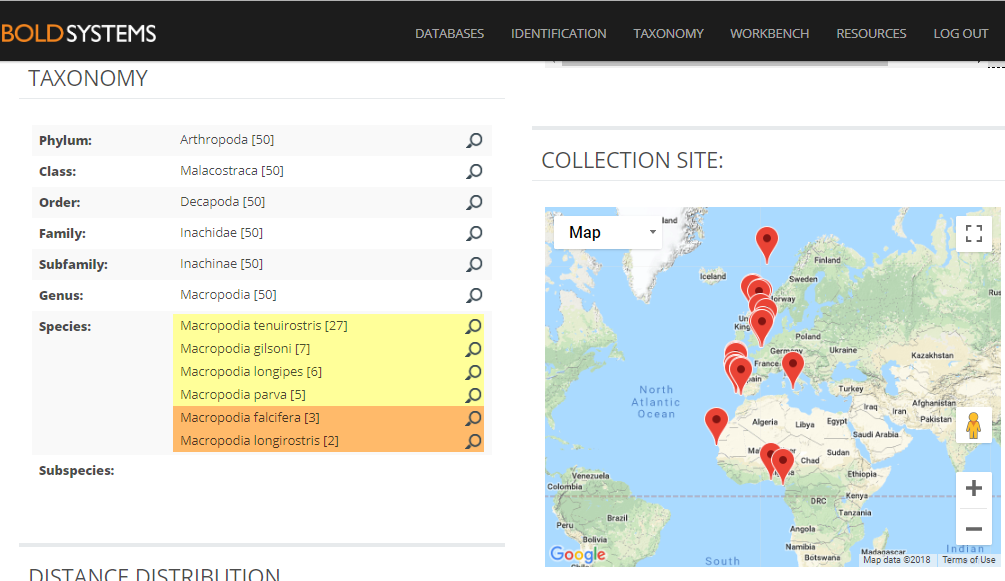

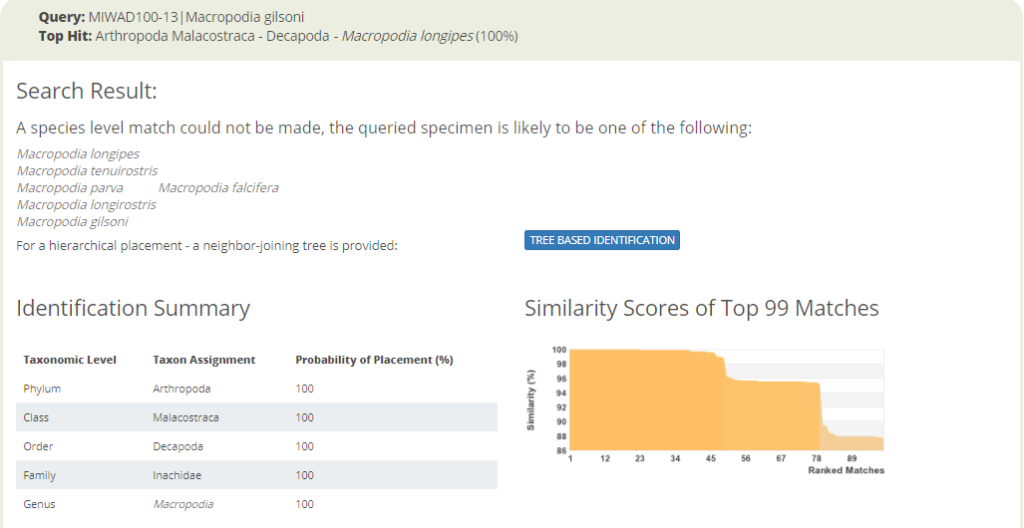

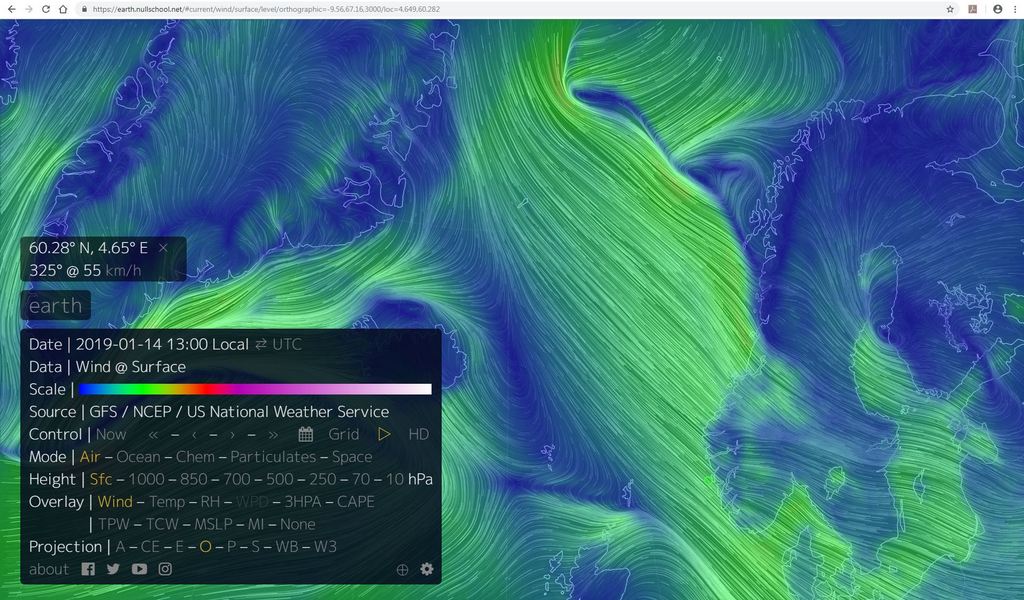

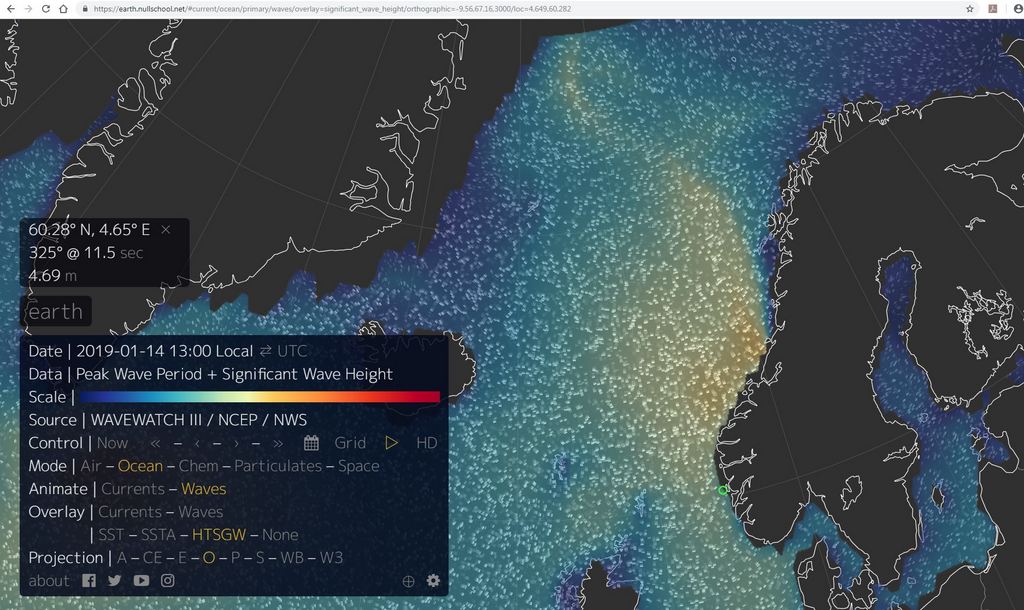

The forecast was quite a bit of wind (15 m/s)…

-

-

…and waves (https://earth.nullschool.net/). In the end it was not as bad as predicted!

Our main target for the day was actually not connected to any of the NTI-projects – we were hunting for the helmet jellyfish, Periphylla periphylla. We need fresh specimens that can be preserved in a nice way, so that they can be included in the upcoming new exhibits we are making for our freshly renovated museum. We were also collecting other “charismatic megafauna” that would be suitable for the new exhibits.

We have been getting Periphylla in most of our plankton samples since last summer, so when we decided this was a species we would like to show in our exhibits about the Norwegian Seas, we did not think it would be a big problem to get more.

This is a species that eats other plankton, so normally when we get it, we try to get rid of it as fast as possible; we want to keep the rest of the sample! But we should have known. Don’t ever say out loud you want a specific species – even something very common. Last November, we planned to look specifically for Periphylla, and we brought several extra people along just because of that. But not a single specimen came up in the samples – even when we tried where we “always” get them…

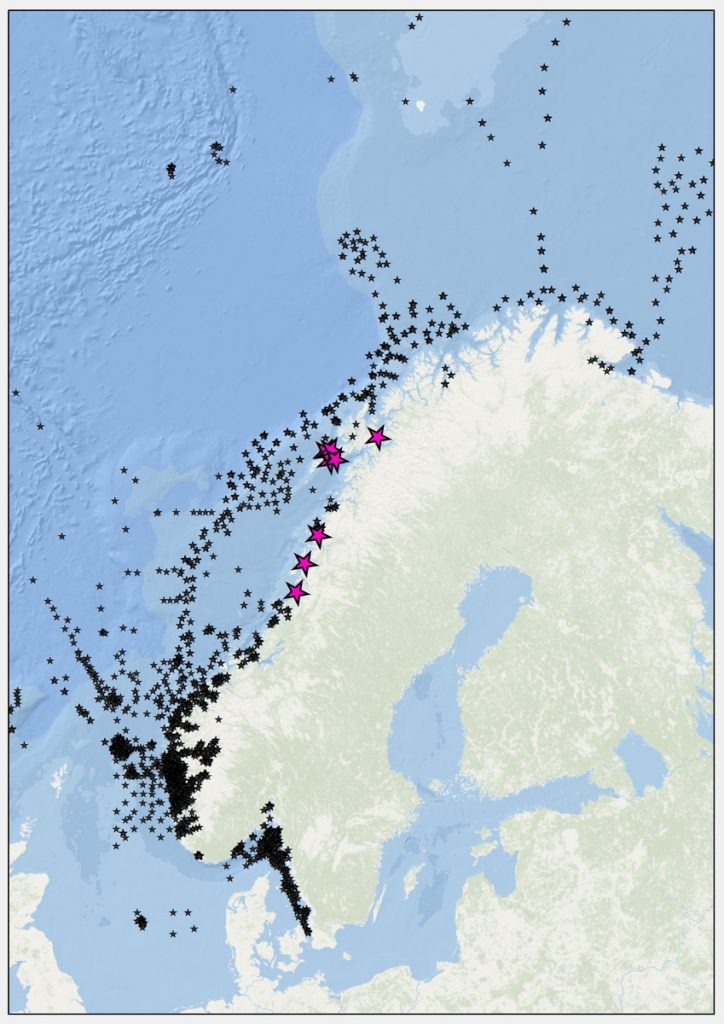

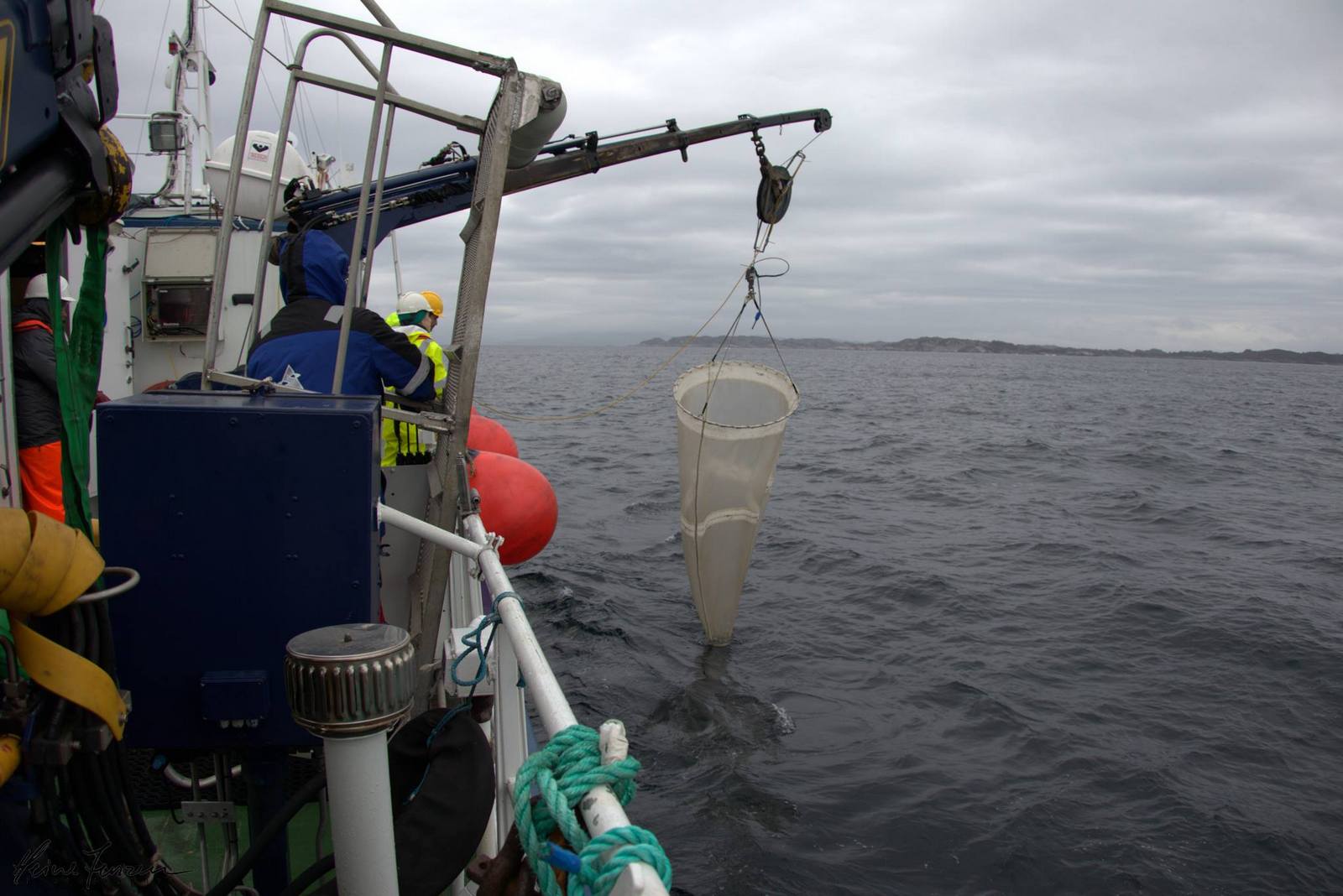

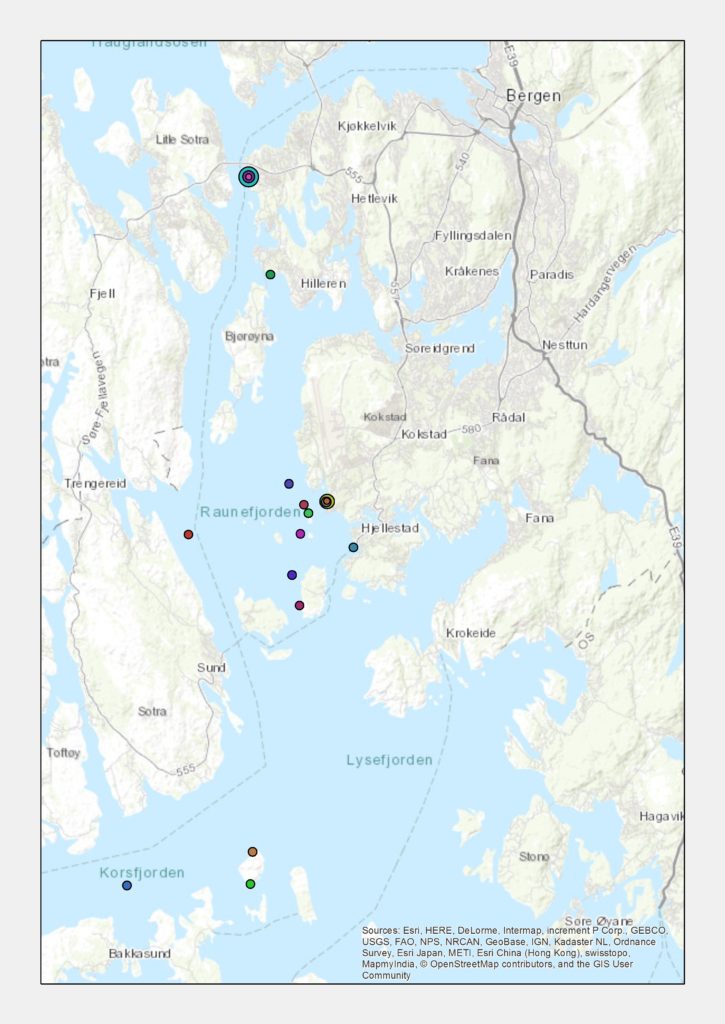

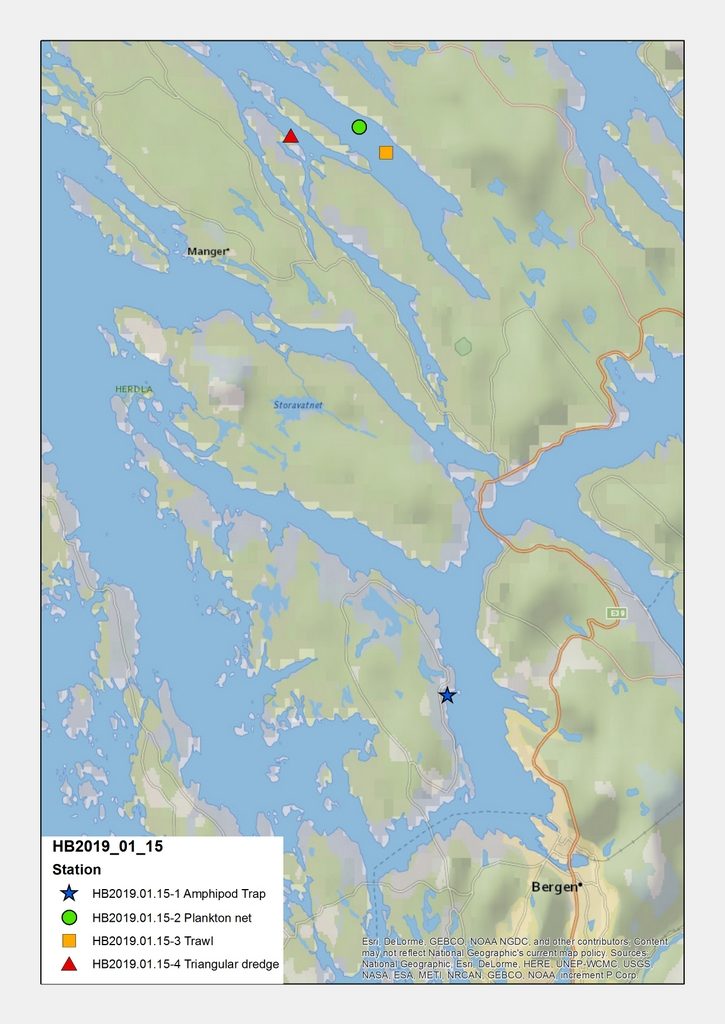

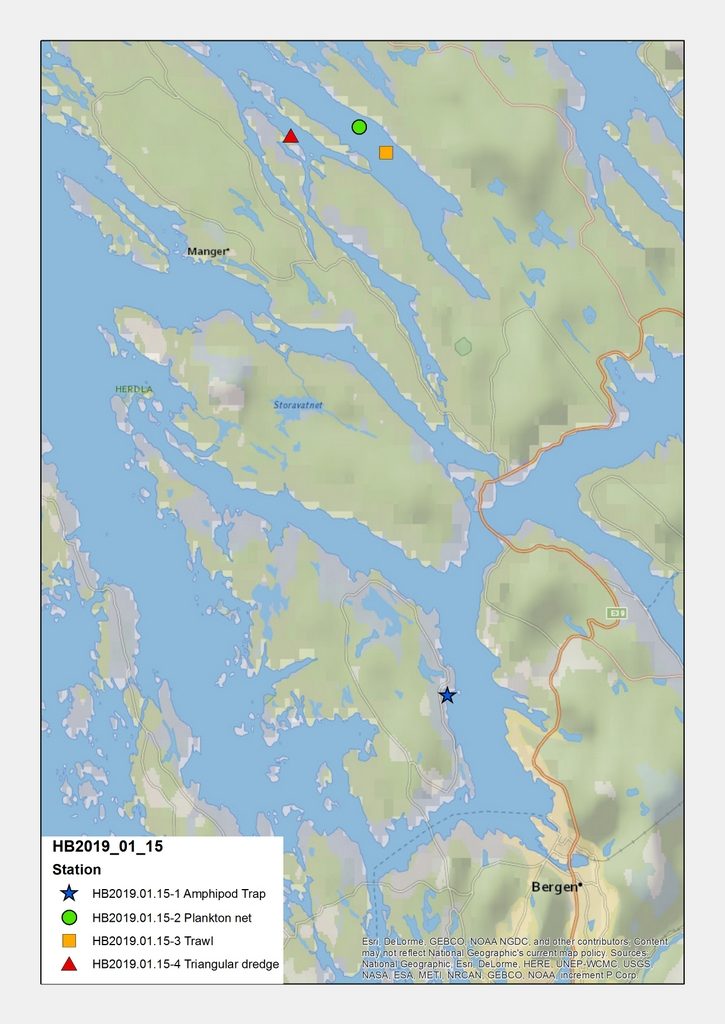

Lurefjorden is famous for being a hotspot for Periphylla – so the odds were in our favor! Map: K. Kongshavn

Wise from Novembers overconfident cruise, this time we planned to call to the lab IF we got anything to preserve. The Plankton-sample did not look too good for Periphylla: we only got a juvenile and some very small babies. So we cast the bottom-trawl out (the smallest and cutest trawl any of us have ever used!), and this sample brought us the jackpot! Several adult Periphylla, and a set of medium-sized ones as well! Back in out preparation-lab an entire size-range of the jelly is getting ready for our museum – be sure to look for it when you come visit us!

-

-

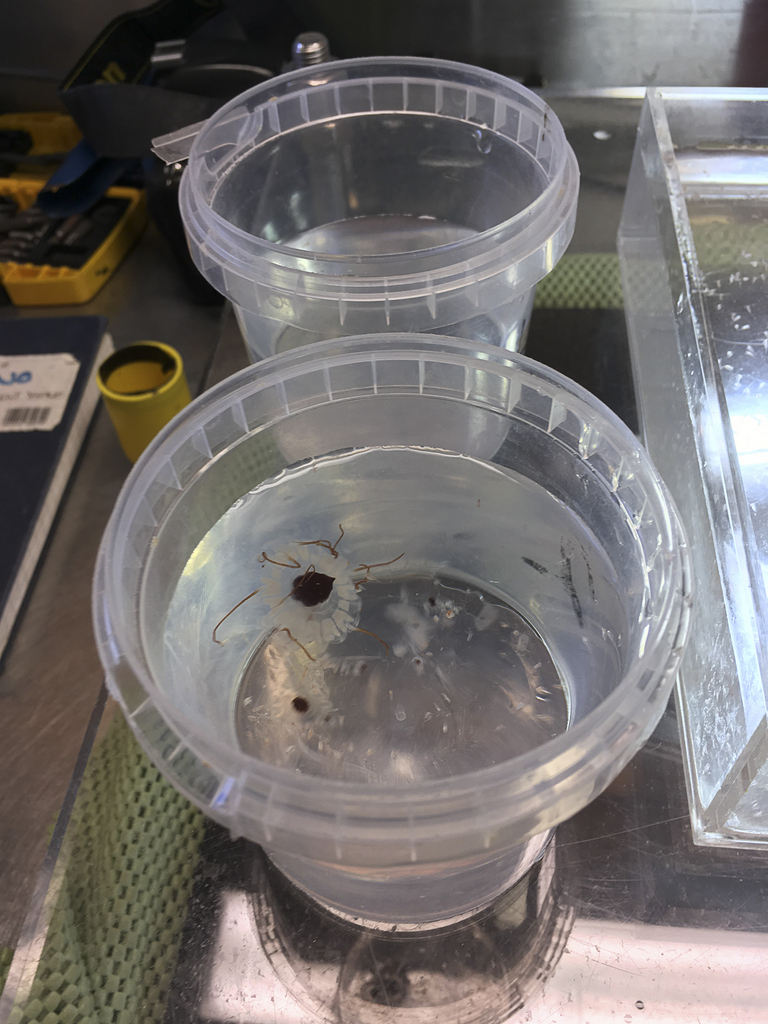

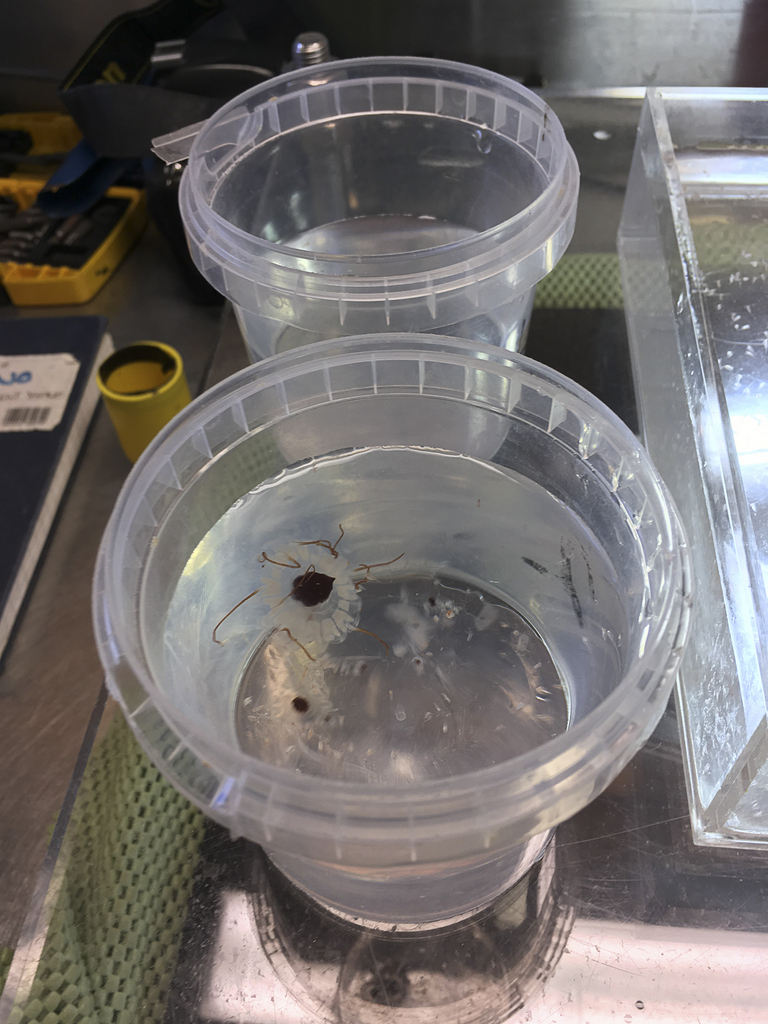

First glimpse of Periphylla – these were a bit too small for what we have in mind…(Photo: AHST)

-

-

Jackpot! (Photo: K.Kongshavn)

-

-

Pretty specimens were selected for the exhibits (Photo: K.Kongshavn)

-

-

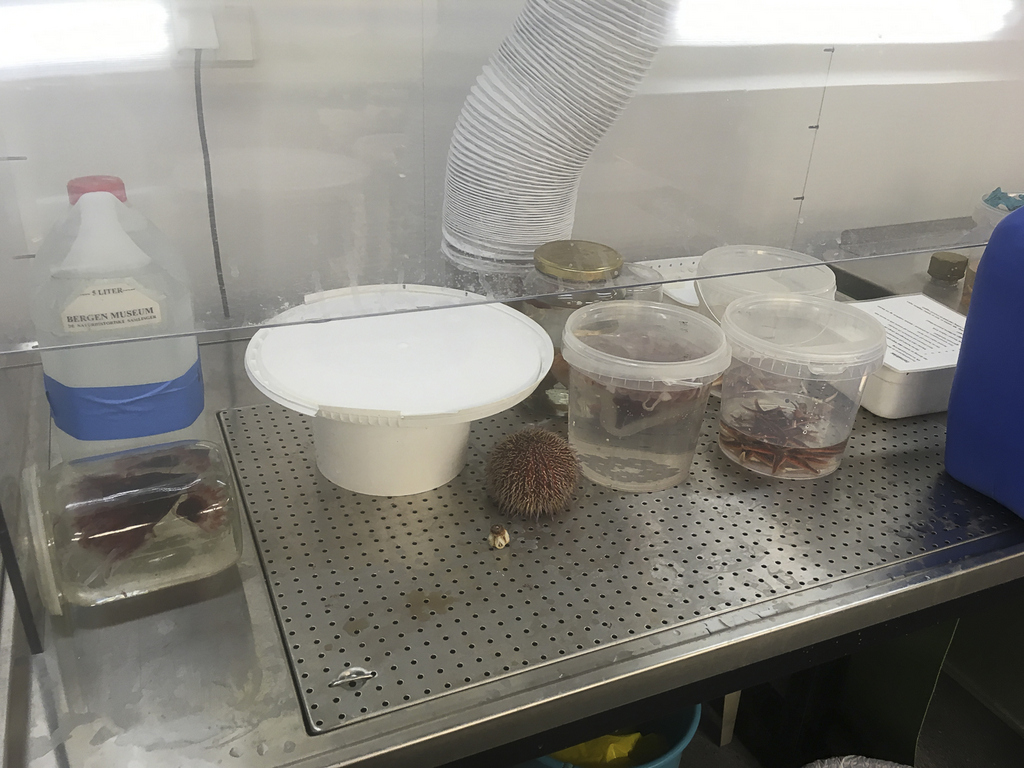

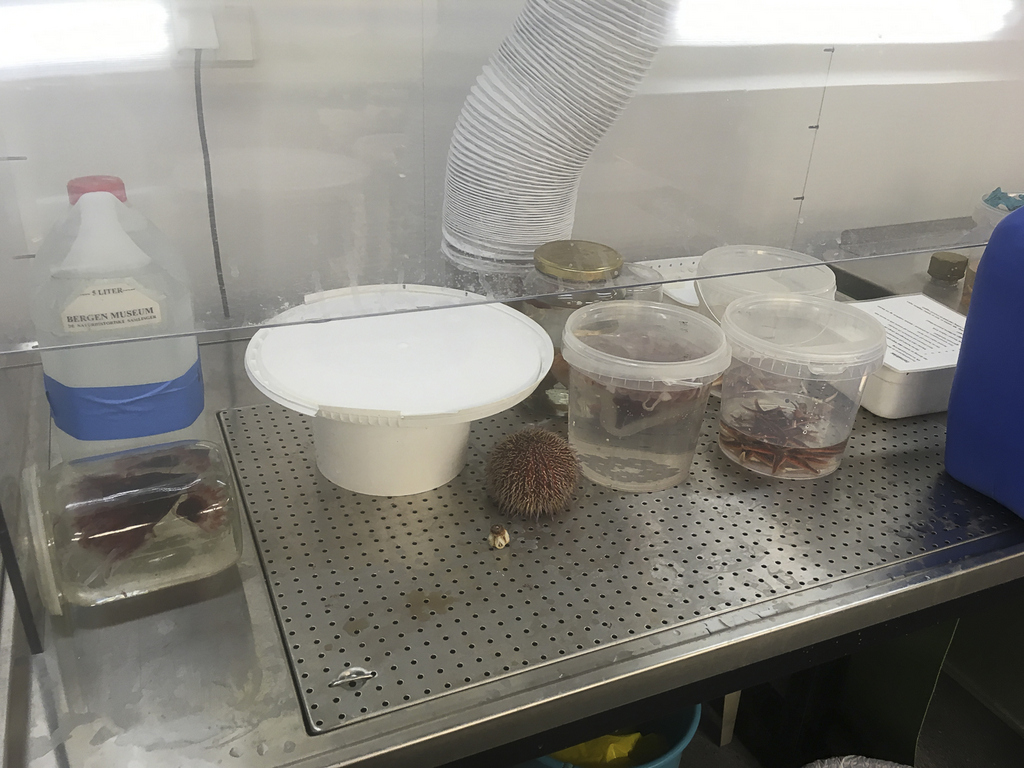

Preservation underway in the lab (Photo: AHST)

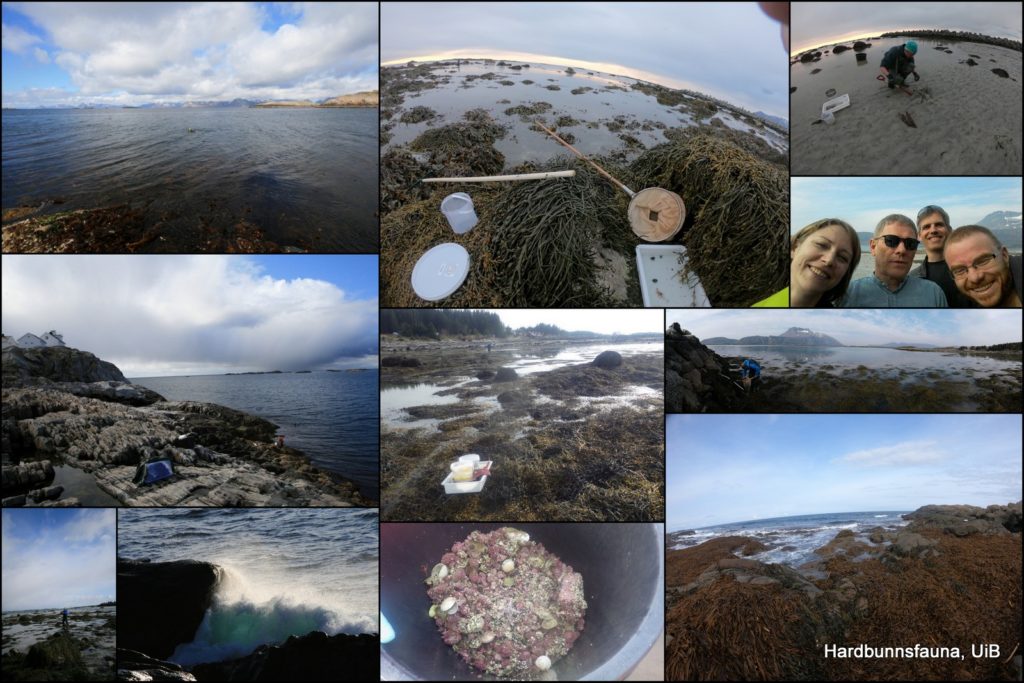

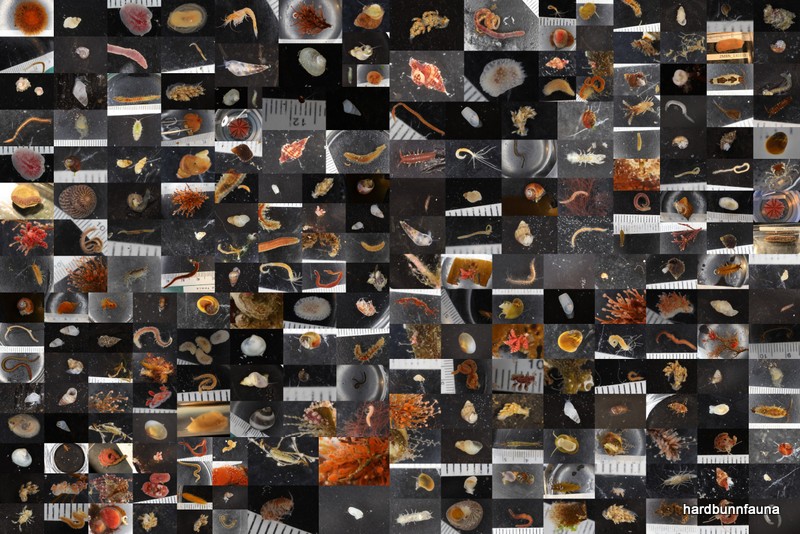

We of course wanted to maximize the output of our boat time– so in addition to Periphylla-hunting, we sampled for plankton (also to be used for the upcoming ForBio-course in zooplankton), tested the traps that NorAmph2 will be using to collect amphipods from the superfamily Lysianassoidea, checked the trawl catch carefully for nudibranchs (Sea Slugs of Southern Norway, SSSN) and benthic Hydrozoa (NorHydro), and used a triangular dredge to collect samples from shallow hard-bottom substrate that can be part of either SSSN or the upcoming projects NorHydro (“Norwegian marine benthic Hydrozoa”) or “Invertebrate fauna of marine rocky shallow-water habitats; species mapping and DNA barcoding” (Hardbunnsfauna).

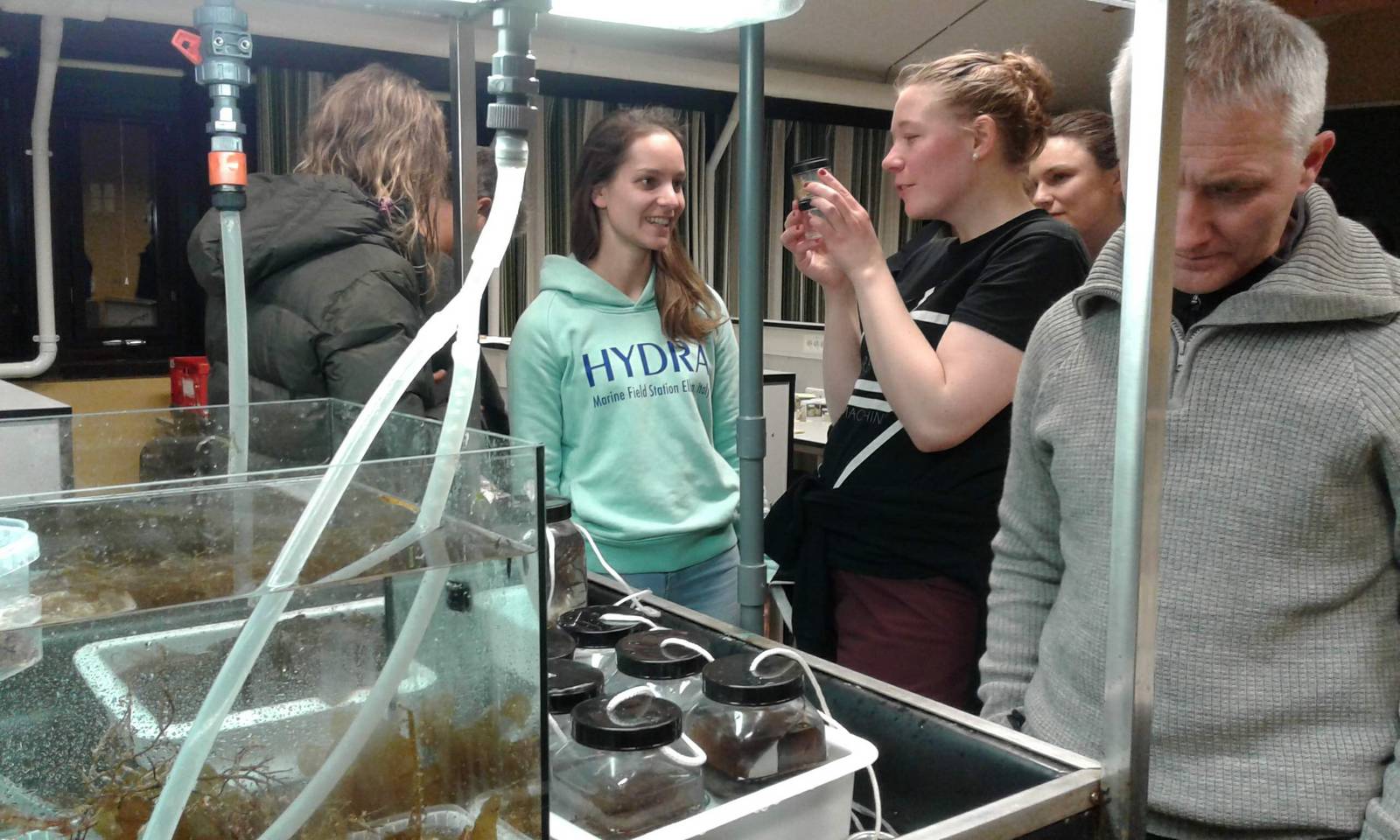

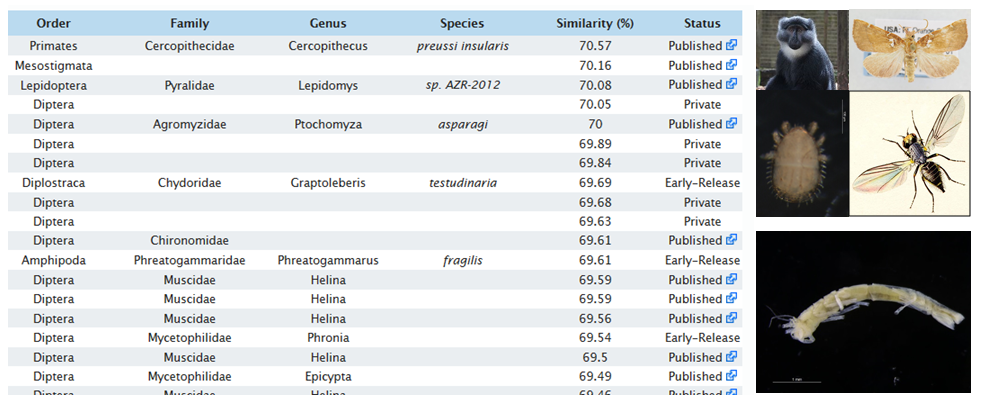

The Hardbunnsfauna project was especially looking for Tunicates that we didn’t already have preserved in ethanol, as we want to start barcoding these once the project begins in earnest (last week of March). We also collected bryozoans, some small calcareous sponges, and (surprise, surprise!) polychaetes.

-

-

The tunicate Boltenia echinata (1.5 cm). Photo: K.Kongshavn

-

-

The polychaete Eupolymnia nebulosa. Animal about 6 cm when uncurled. Photo: K.Kongshavn

-

-

A shell with fauna hiding inside…

-

-

Once evicted, there were quite a few animals in the shell!

-

-

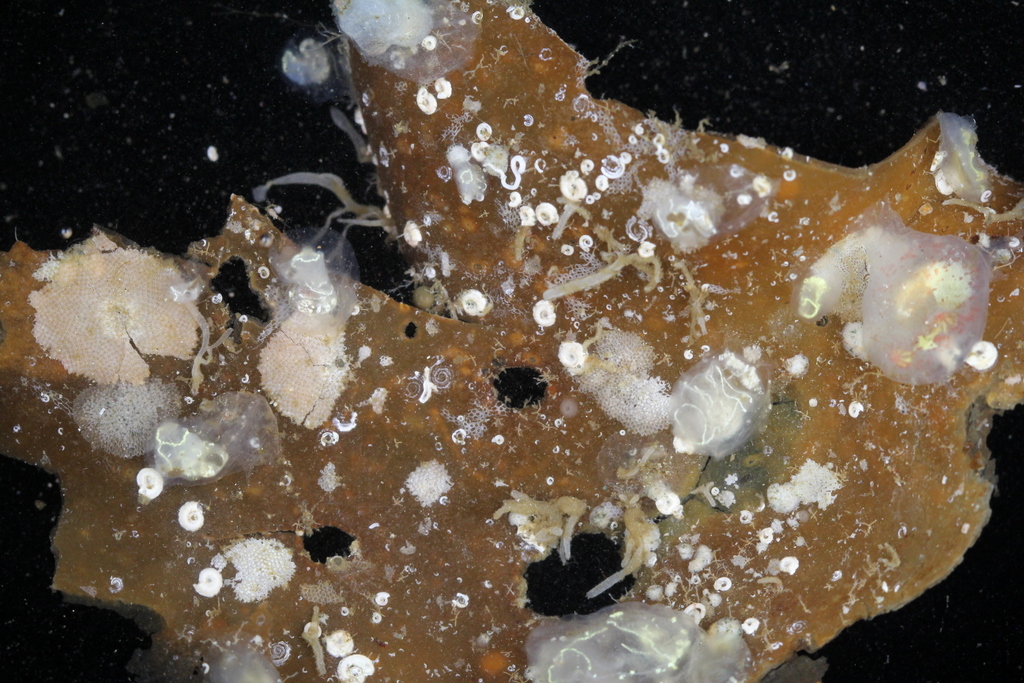

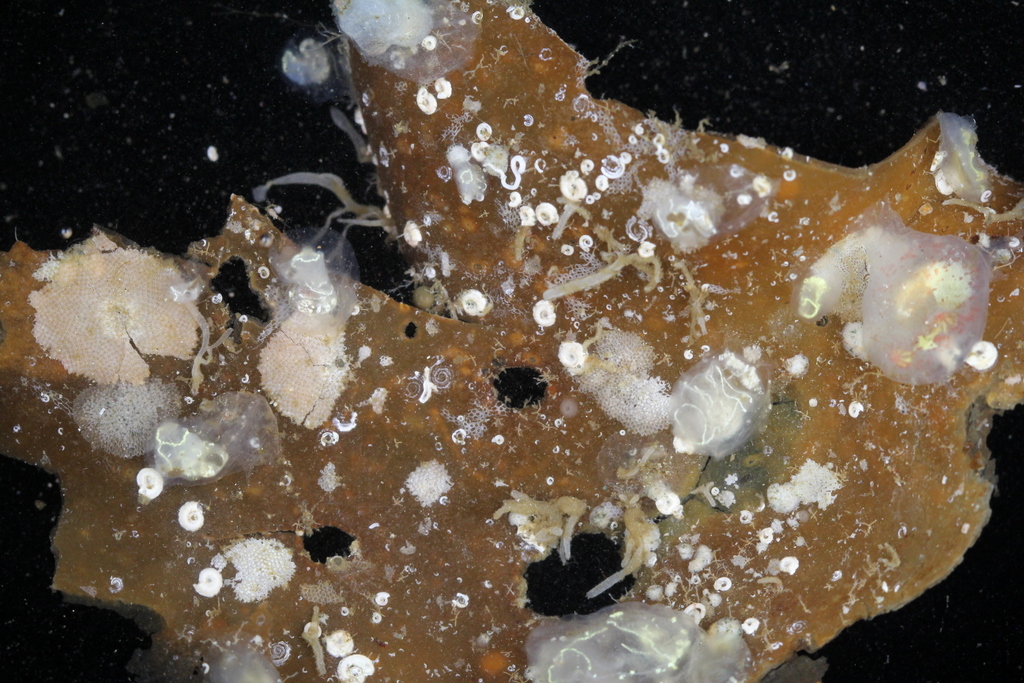

A piece of sugar kelp, Laminaria saccharina, with encrusting fauna; bryozoa, tunicates, and polychaetes. Photo: K. Kongshavn

-

-

The holdfast of a sugar kelp with animals growing on it. Photo: K. Kongshavn

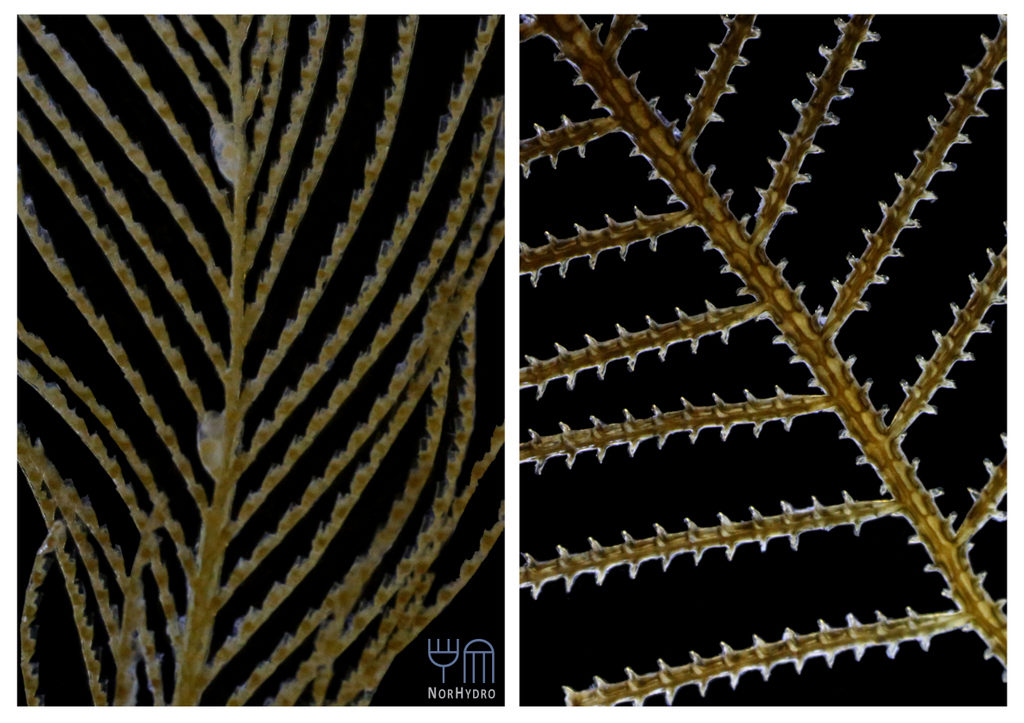

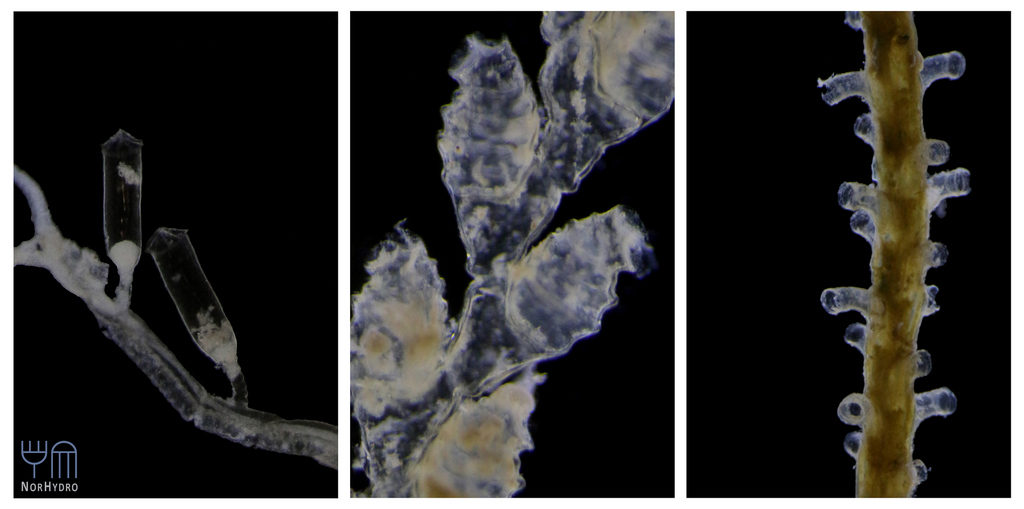

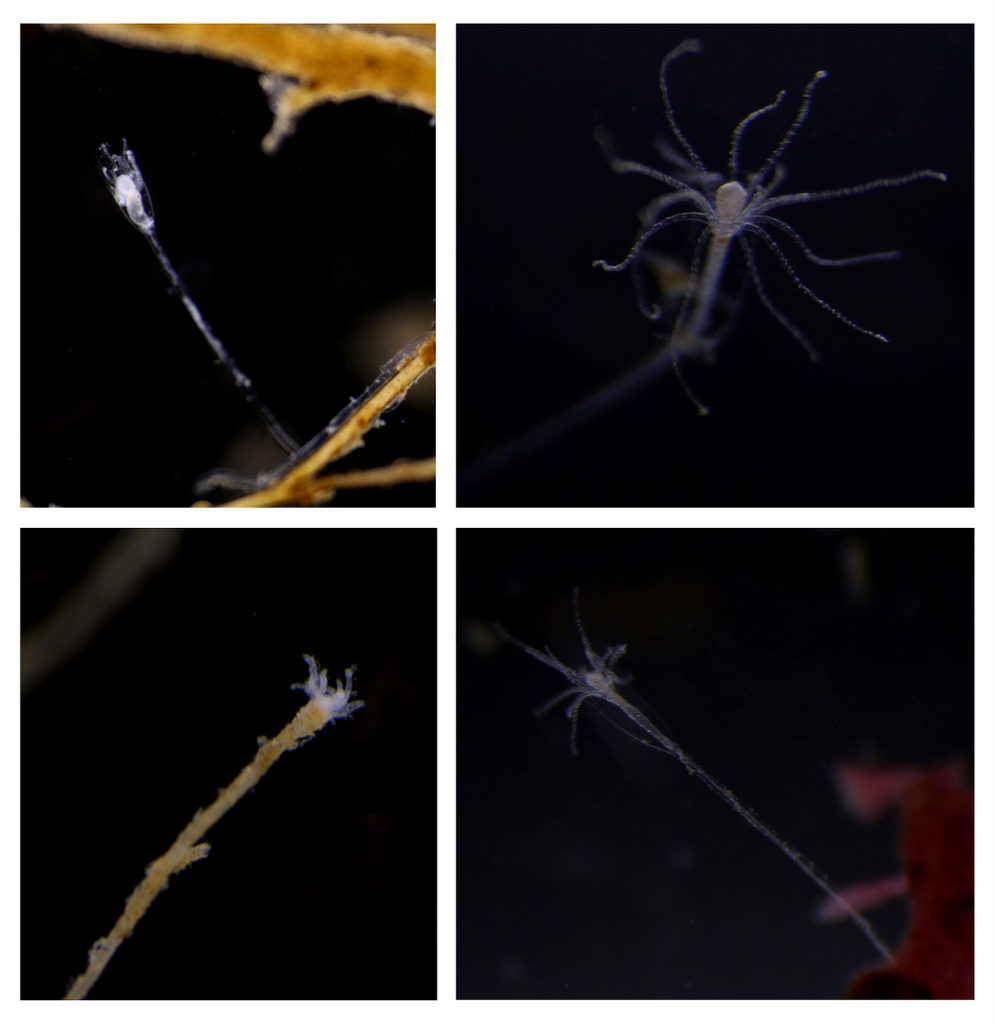

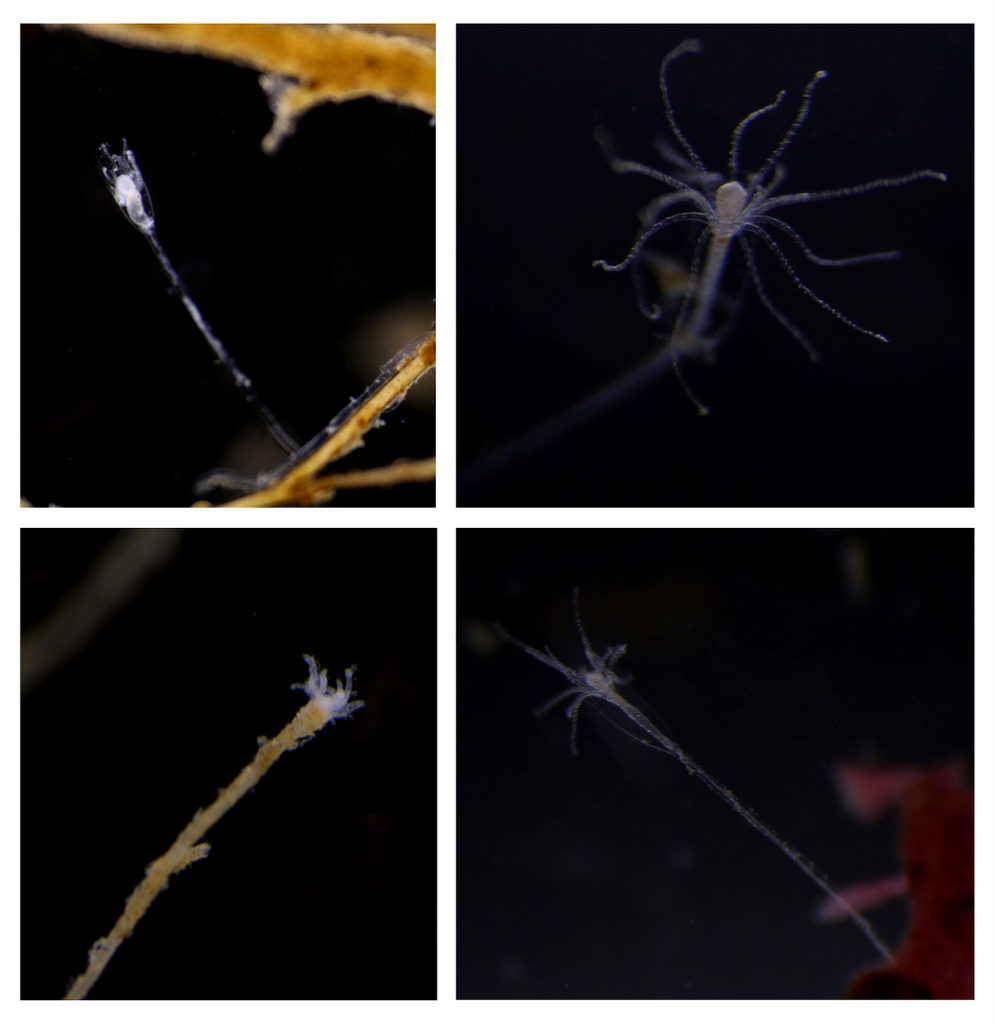

When it comes to hydrozoans, we were lucky to find several colonies of thecate hydroids from families Campanulariidae and Bougainvilliidae that represent some of the first records for NorHydro. Hydroid colonies growing on red and brown algae were particularly common and will provide a nice baseline against which diversity in other localities will be contrasted.

Different hydroid colonies growing on algae and rocks at the bottom of Lurefjorden. Photo: L. Martell

There were not a lot of sea slugs to be found on this day, but we did get a nice little Cuthona and a Onchidoris.

-

-

Cuthona sp. (maybe C. foliata?) About 3 mm.. Photo: K.Kongshavn

-

-

Onchidoris (photo: C. Rauch)

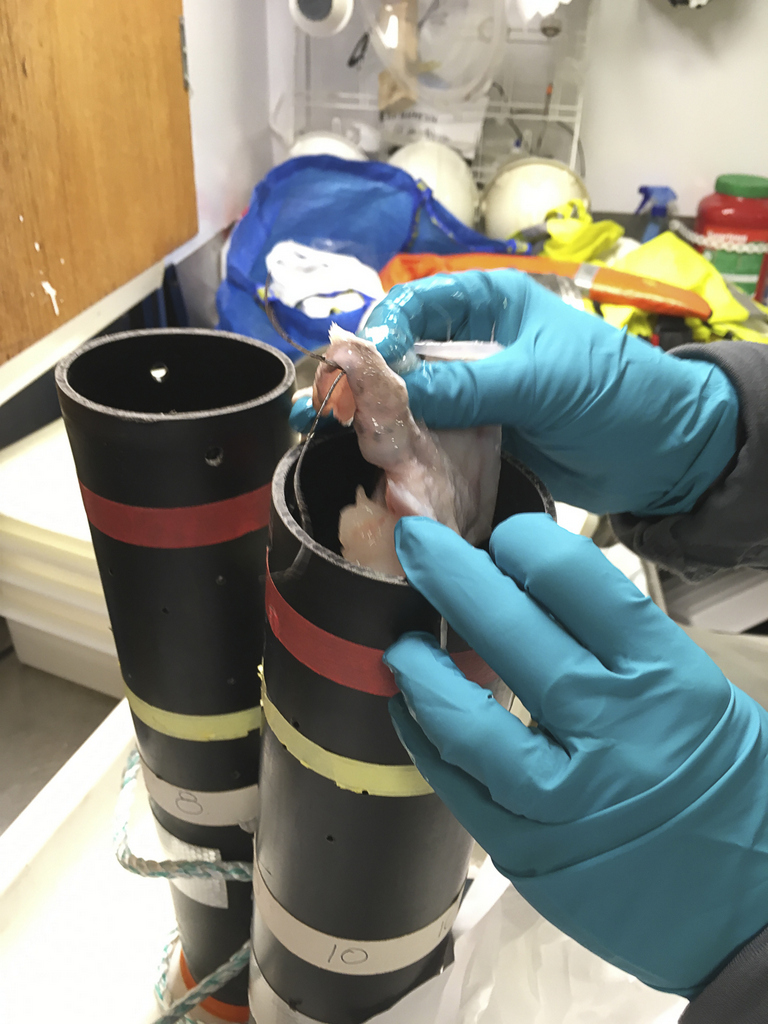

But what about the Amphipod-traps? Scavengers like Lysianassoidea need some time to realize that there is food around, and then they need to get to it. Our traps have one small opening in one end, but the nice smell of decomposing fish also comes out in the other end of the trap. We therefore normally leave traps out at least 24 hours (or even 48), and at this trip we only had the time to leave them for 7 hours. The collected result was therefore minimal – we even got most of the bait back up. However, knowing that we have a design we can deploy and retrieve from the vessel is very good, and we got to test how the technical details work. It was quite dark when we came to retrieve the traps, so we were very happy to see them! All in all not so bad!

-

-

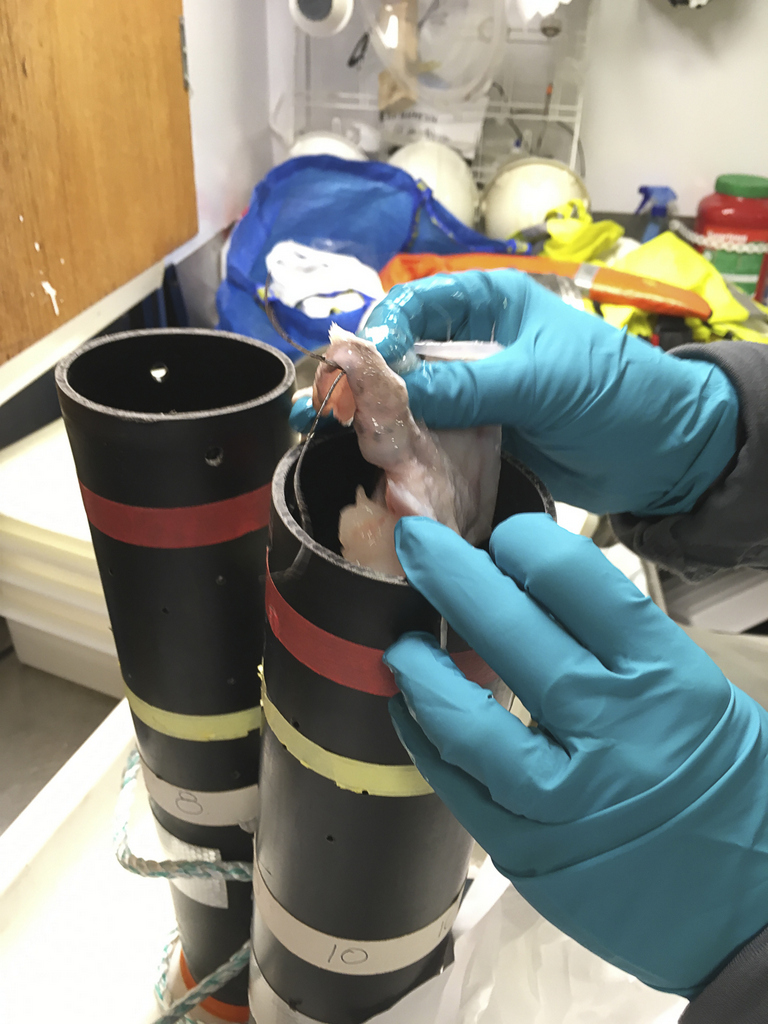

Baiting the traps with fish (Photo: K.Kongshavn)

-

-

Traps away! (Photo: L.Martell)

-

-

It got quite dark by the time we picked the traps up again (Photo: AHST)

We had a good day at sea, and it will be exciting to see some of our animals displayed in the new exhibits!

If you want to know more about our projects, we are all planning on blogging here as we progress. Additionally you can find more on the

-Anne Helene, Cessa, Luis & Katrine