Askøy Seilforening 24th till 26th of August 2018

by Cessa Rauch

Jentedykketreff

Every year a group of female divers from all over Norway organize a meetup at one of the many beautiful dive sites along the Norwegian coast. This year they decided to meet up in Askøy at the local seilforening. As this is close to Bergen, me and my colleague Justine Siegwald decided to check it out and see what the ladies would encounter underwater. The meetup was short, and so was our fieldwork, but nevertheless the participants were able to collect a bunch of sea slugs and we added 6 more species to our database, hurray for our citizen scientists!

Sea slugs of Southern Norway – so far

The sea slugs of Southern Norway project is a two-year project funded by Artsdatabanken with the aim of mapping the biodiversity of sea slugs along the Southern part of the Norwegian coast. The focal area stretches from Bergen, Hordaland, all the way down to the Swedish border. From the beginning we have made an effort to engage divers and underwater photographers passionate about sea slugs and establish a network of Citizen Scientists, and the response was extremely positive. Citizen scientists are volunteers that help out scientists by providing them with data as a hobby in their spare time. In May the project had its first official launch with a successful expedition to Drøbak, a little village well known for its marine biology institute, near Oslo in the Oslofjords. In just two weeks we were able to collect around 43 species.

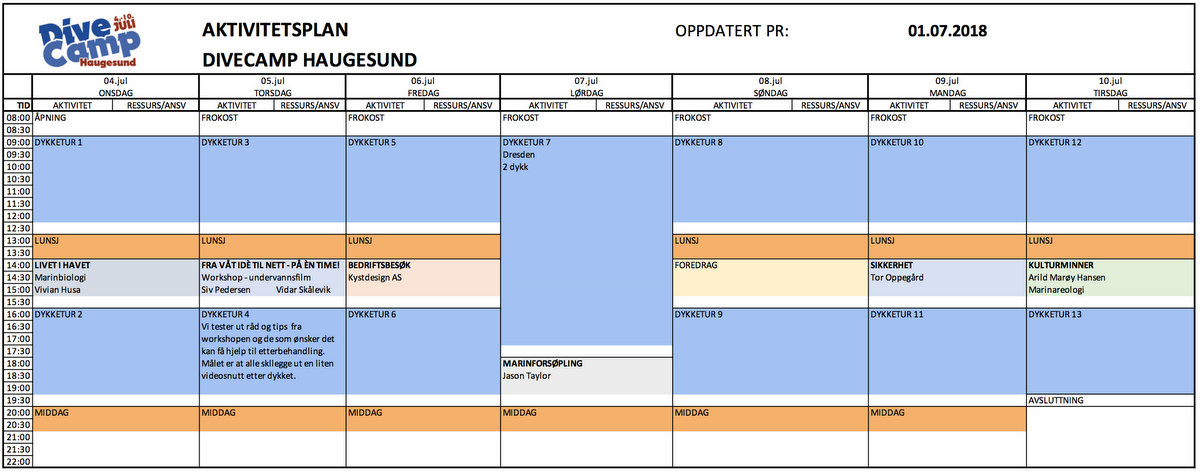

Two months later we headed to Haugesund to attend the Slettaa Dykkerklubb dive camp. This camp covered two weeks and attracted many participants. During the dive camp I lectured about sea slugs and especially how to find, recognize and collect them. It was a huge hit and Sea slugs of Southern Norway suddenly counted many new citizen scientists. They were able to add another 22 sea slug species to our database.

What did you do this weekend?

Friday afternoon Justine and I were picked up from the institute by the organizer of this years’ yentedykketreff; Gry Henriksen.

We actually didn’t really communicate well enough about the car size and very soon we realized that with our personal belongings and portable laboratory gear the car changed into a game of Tetris

Luckily everything fitted and off we went for our short car ride to Askøy Seilforening. Just a little over an hour drive later we arrived at our destination and we were amazed to see what a luxurious weekend was waiting of us. The seilforening lets us use basically all the space they had, which consisted of a big warehouse were the participants could store their gear, a big ‘club’ house with a kitchen and enough space for all participants to have dinner together. Not to mention the eight tiny houses right at the shore, provided with everything you needed and more.

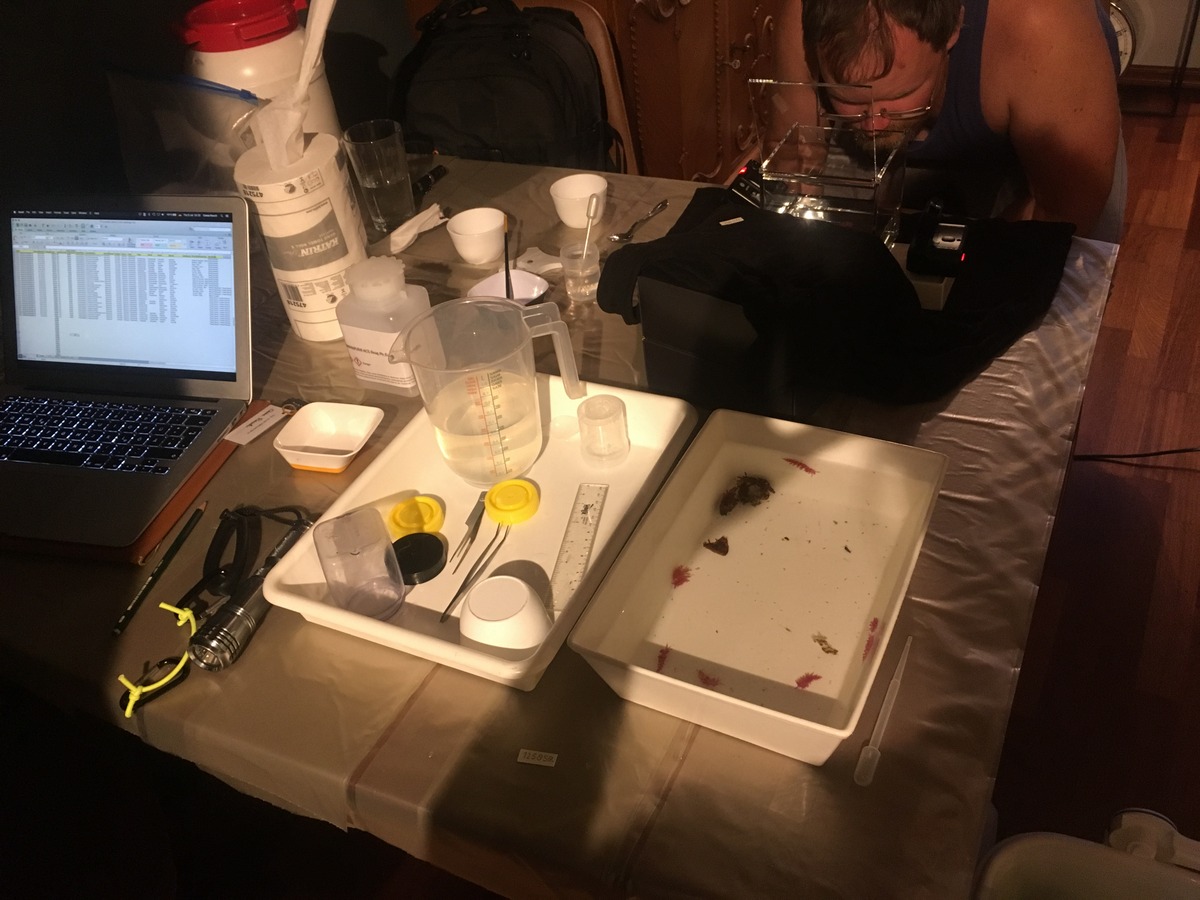

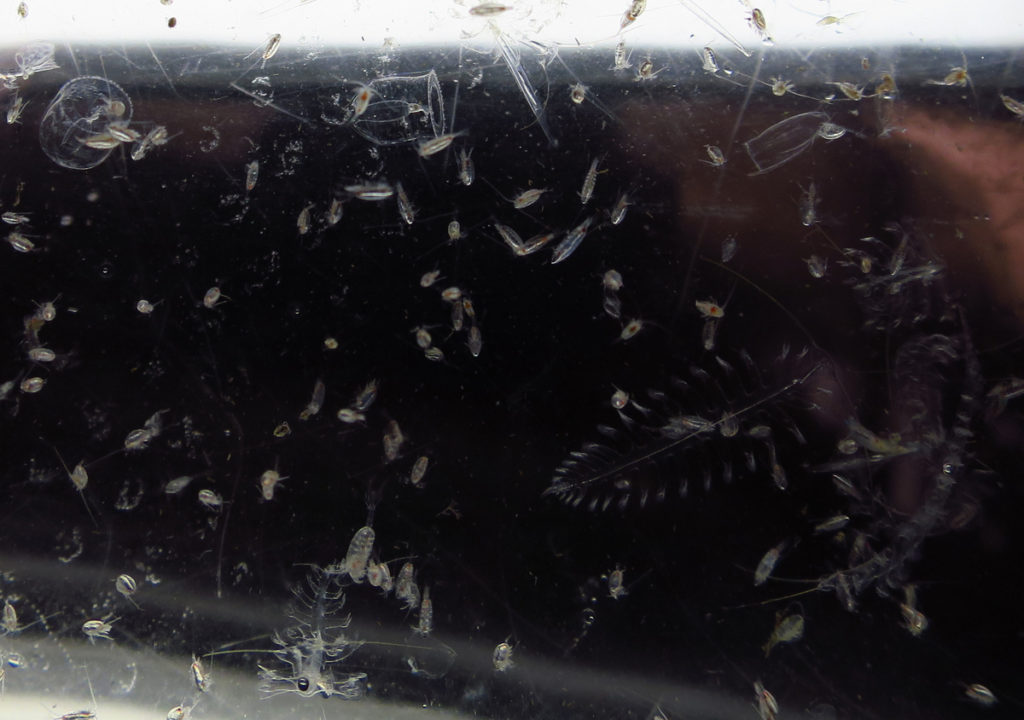

Right after the arrival Justine and I converted the living room of our rental holiday home to a popup sea slug laboratory as that same evening the ladies already went for their first dive and of course collected some sea slugs for us.

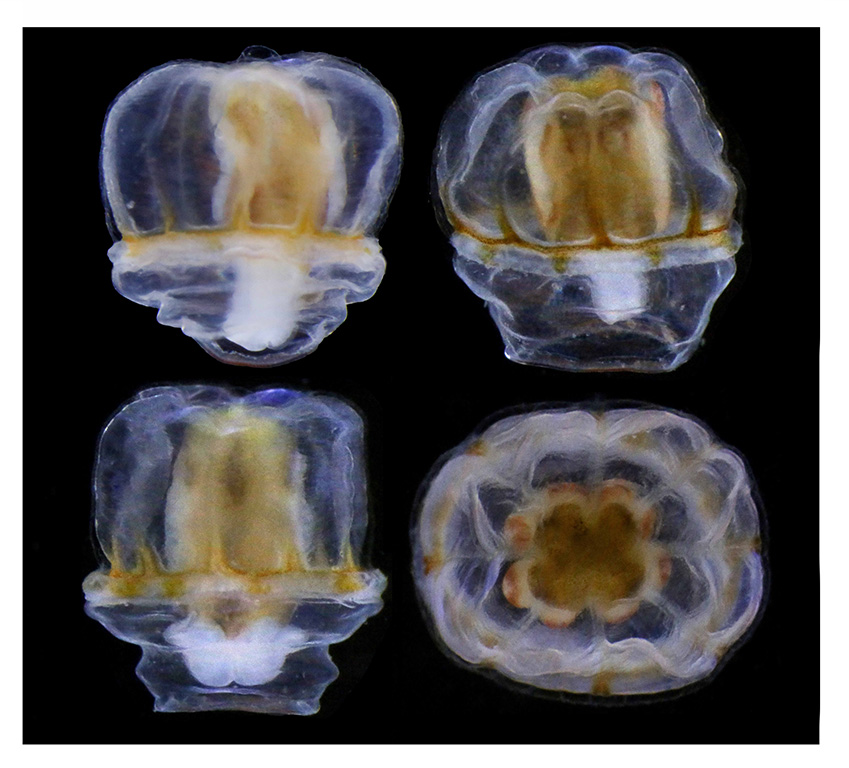

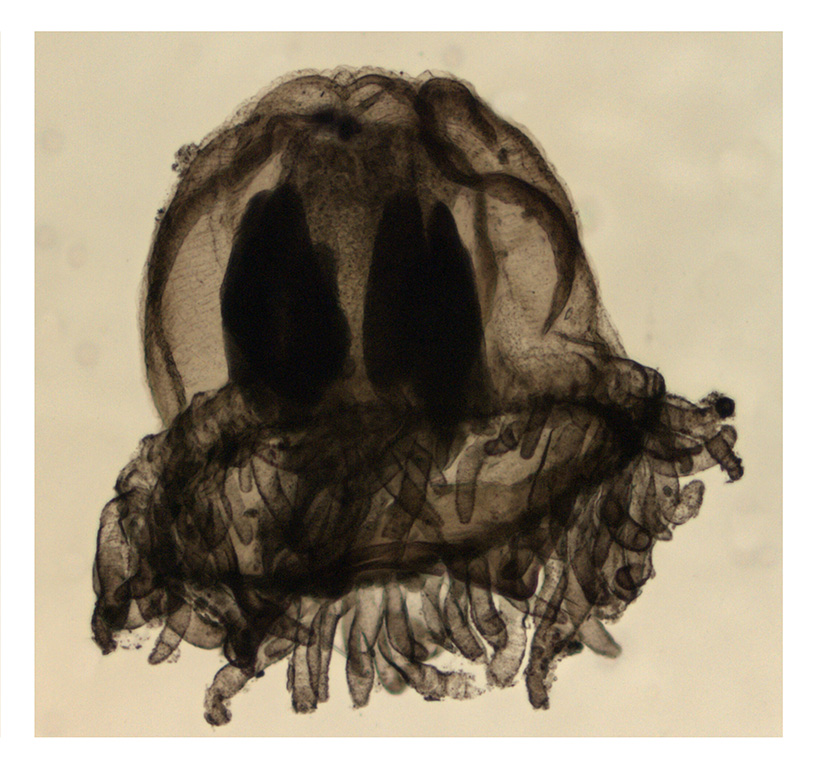

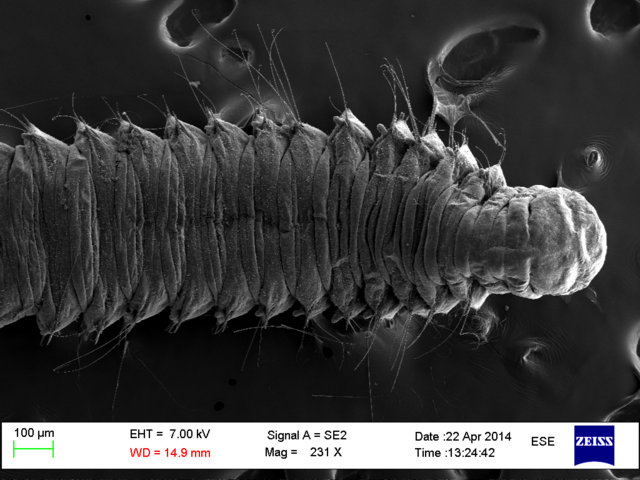

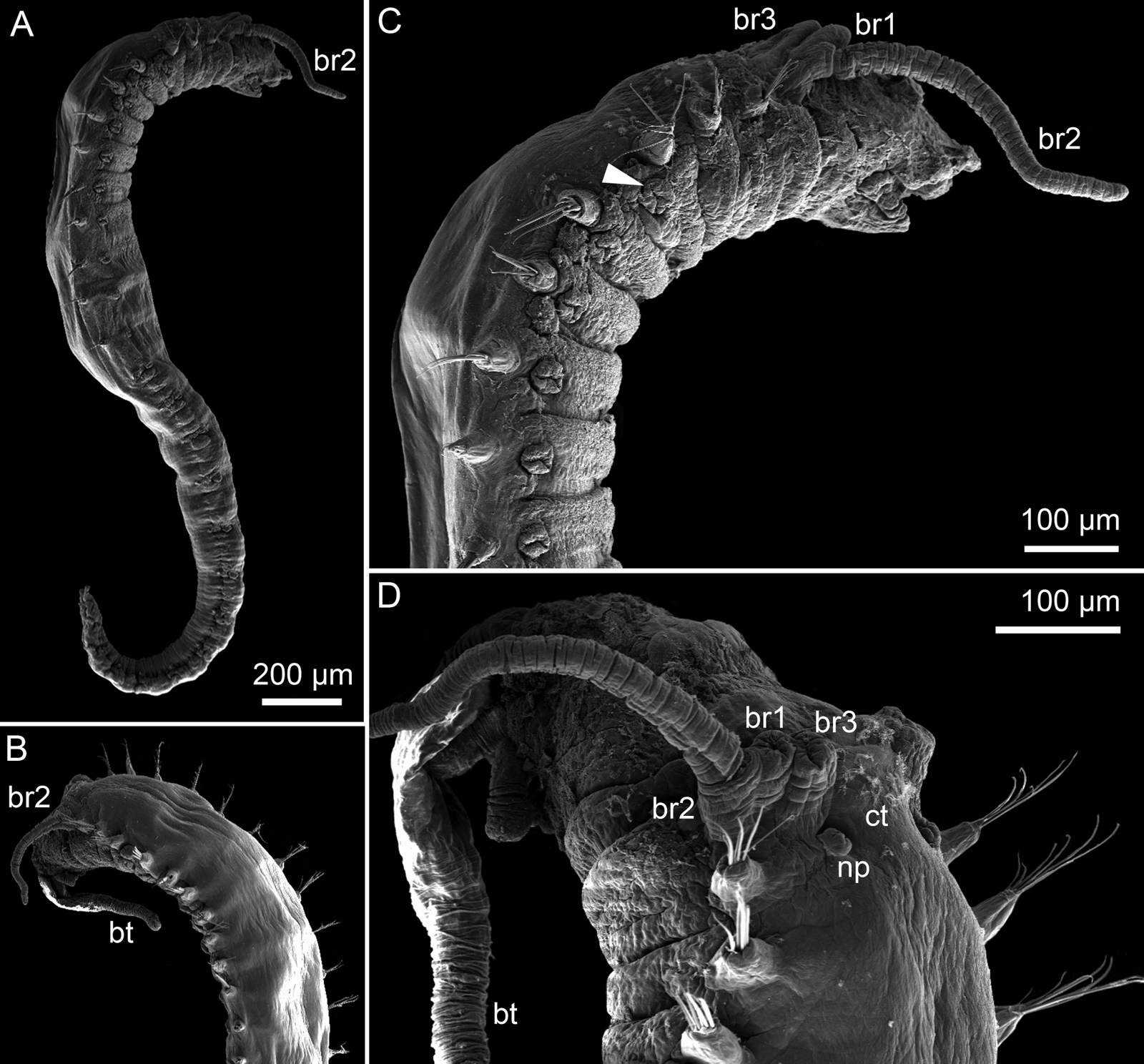

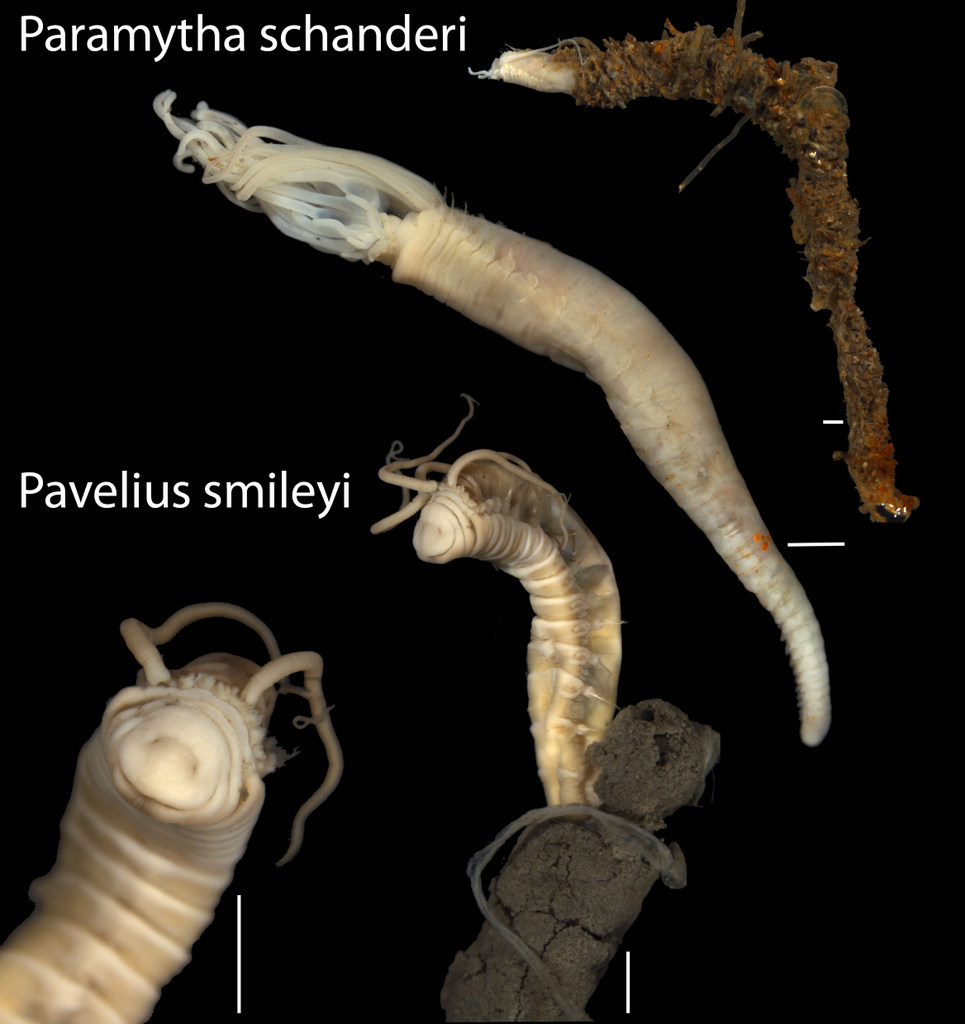

It is not real sea slug season anymore (best times are more towards winter and early spring) so the collections were dominated mostly by two species; Limacia clavigera and Adalaria loveni.

But as the weekend progressed we could add some variety to this list with species as Elysia viridis, Aplysia punctata, Edmundsella pedata and Cadlina laevis

On Saturday, after dinner, I gave a short talk about the project and showed the participants pictures of the slugs and brought sampling kits for whoever wanted to contribute to the project. That same day some divers had already collected species which we put in a plastic tray so everyone could have another good and detailed look at

A memorable success of the weekend was that Gry Henriksen found her first Elysia viridis in the wild during her dive after Justine and I carefully described the way to spot them. Elysia viridis is often overlooked by divers because it lives relatively shallow, between 1 maximum 5 meters. It mostly sits in the green algae (or red as we see it in the picture above) . It is actually easier to see them while snorkeling than diving, but it is still possible! On the last day of the event Gry found hers and collected them for the project! Sunday most off our activities consisted of packing our gear and await one more last catch of slugs from the morning dive. Even though the amount of new species to the list was low, I was happy that we were welcome during this get together weekend as both me and Justine met a lot of old and new faces and were able to engage them into the project. The participants inspired us for setting up a ‘sea slug course’ that we hope to be able to realize the end of this year together with Gry Henriksen and the Askøy Seilforening! So, keep your eyes out for the next blog post as a lot off activities within the project are still to come!

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Justine Siegwald for being an excellent helping hand during the weekend. And I would like to thank all the participants of the jentedykketreff; Runa Lutnæs, Brit Garvik Dalva, Sofie Knudsen, Laila Løkkebergøen, Silje Skotnes Wollberg, Sissel Grimen, Hege Nyborg Drange and last but not least, the organizer of this event; Gry Henriksen!

Furthermore

Interested in where we stayed during this weekend? Check out the website of Askøy Seilforening, they have excellent facilities also for (marine biology) courses; http://www.askoy-seilforening.no

Sea slugs of Southern Norway recently got its own Instagram account! Perfect for on the go if you would like to quickly check some species, click here https://www.instagram.com/seaslugsofsouthernnorway/ and don’t forget to follow us.

Curious to the other expeditions we did so far? Read about it in our blogs on the invertebrate website; first fieldwork blog Drøbak may 2018 https://invertebrate.w.uib.no/2018/06/04/fieldwork-and-friendship/ and second fieldwork blog Haugesund July 2018 https://invertebrate.w.uib.no/2018/07/20/seaslug-fieldwork-during-the-haugesund-dive-camp/

Become a member of the sea slugs of southern Norway facebook group, stay updated and join the discussion; https://www.facebook.com/groups/seaslugsofsouthernnorway/

Explore the world, read the invertebrate blogs!