On the 12th of February at the crack of dawn, we had the amazing opportunity to go to Cape Town to attend a Jellyfish workshop. The “we” in question are the three authors of this blog post: Vincent, Vetle, and Håvard. We are master students all working with jellyfish-related topics, and some would go as far as to call us jellyfish enthusiasts. Our work is part of the museum’s Artsprosjekter NorHydro and ParaZoo, and we were happy to represent the invertebrate collections and UMB at this event.

The workshop, held at the Iziko South African Museum, was organized by PRIMALearning and was a collaborative initiative between the University of Bergen and the University of Western Cape. This gave the three of us, accompanied by a few other UiB students not affiliated with the University Museum of Bergen, the chance to visit Cape Town. Some of us for the first time.

On the first day of the workshop, we were greeted outside the museum by Mark Gibbons and his PhD student Michael Brown who was the representative from UWC and would be teaching parts of the workshop. With them was also Anne Gro Vea Salvanes as the representative for PRIMALearning and the University of Bergen, she was also joined by our own UMB scientists Aino Hosia and Luis Martell, who were also part of the teaching team.

The first day included introductions from all the participants, and we got to know each other bit better. We also got a brief introduction to the world of jellyfish and their taxonomy before the night ended with a delicious dinner together with all the participants.

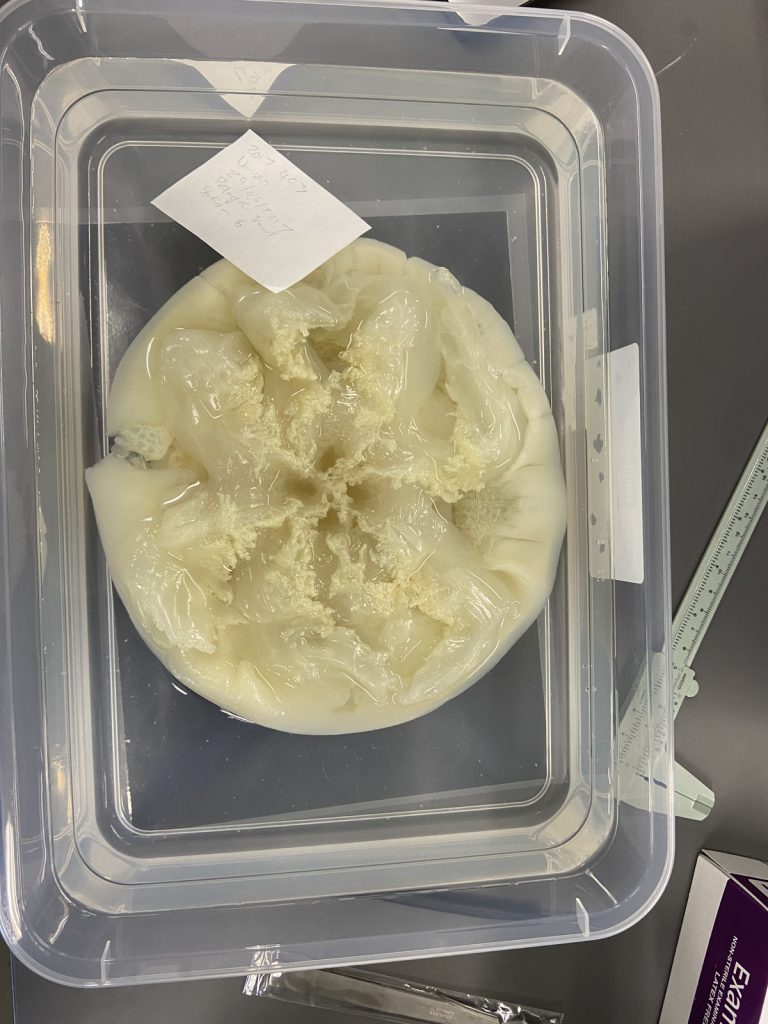

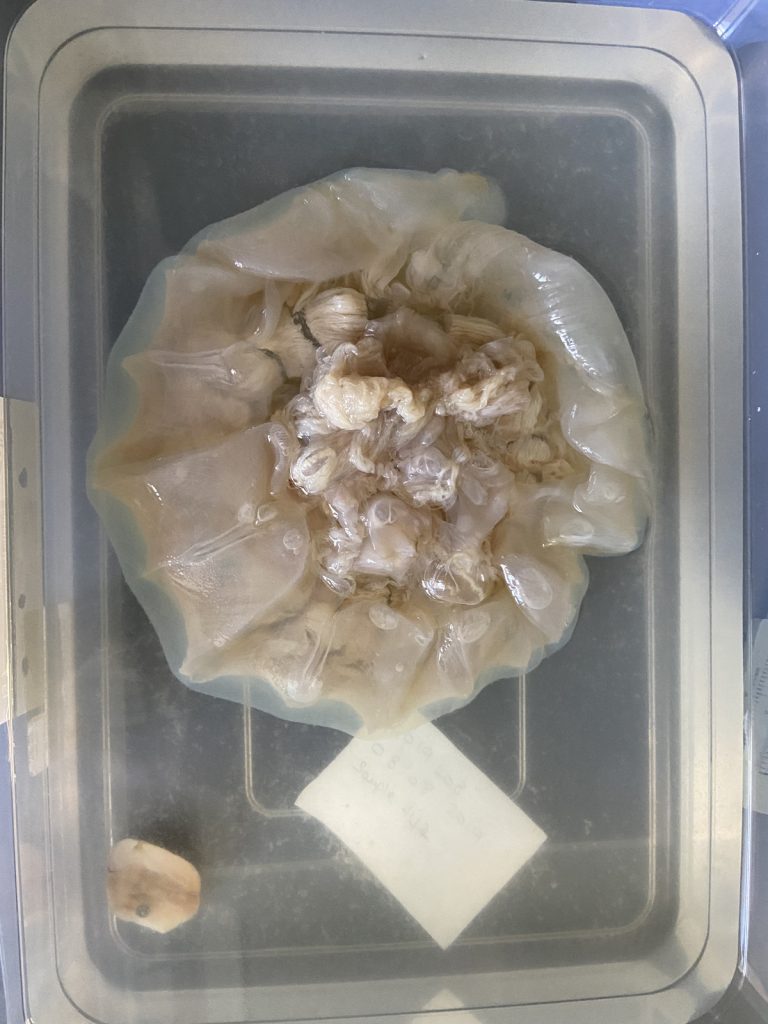

The second day started with lectures about the large or ‘true’ jellies (Scyphozoa), before we got to get our hands dirty looking at preserved samples of jellyfish. We were met with a broad diversity of scyphozoans that was passed around between the students so we would get a shot at identifying them.

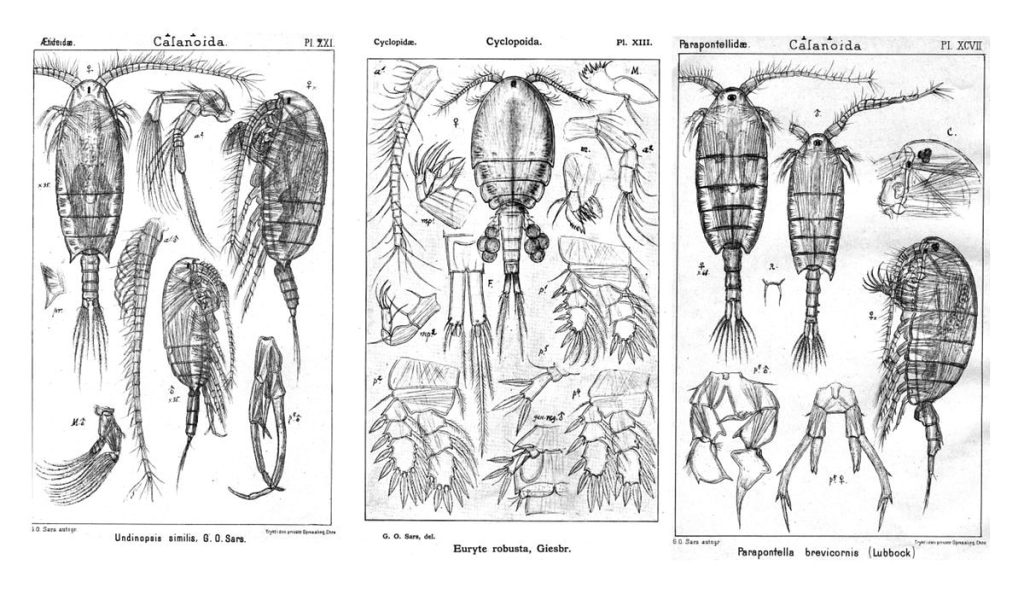

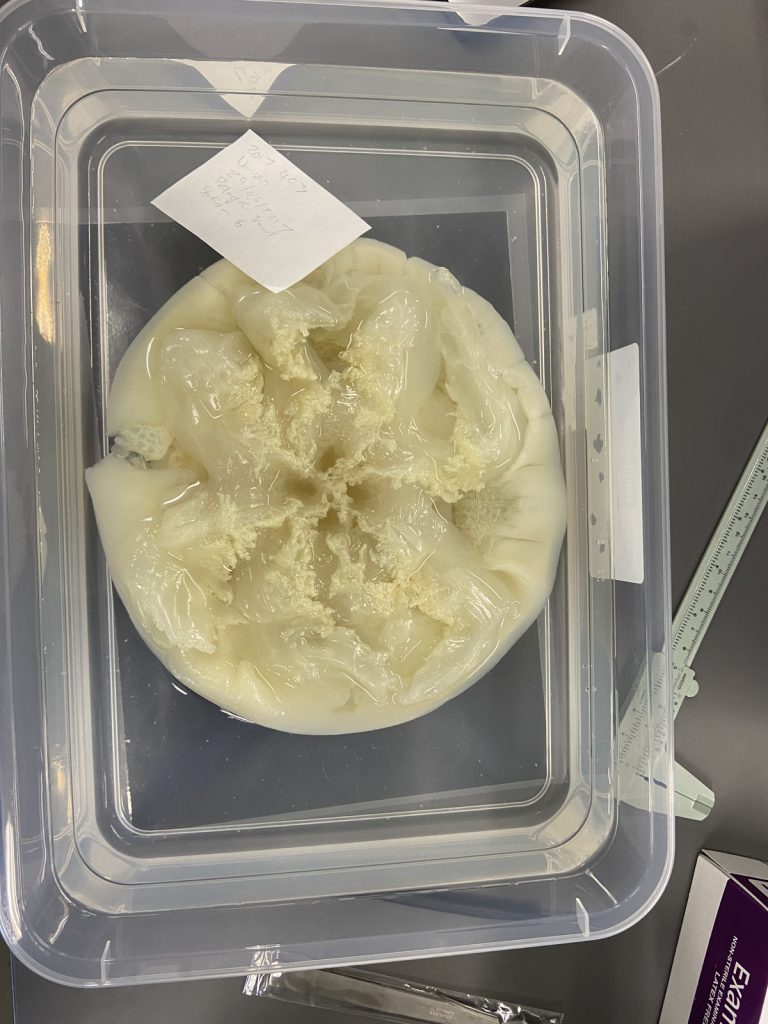

We examined fixed material of scyphozoan jellies representative of the three major groups within the class:

-

-

Rhizostomeae

-

-

Semaeostomeae

-

-

Coronatae (images: Håvard Vrålstad)

The rest of the day after the workshop was spent at the beach, enjoying the sun and local wine. Cape Town is called the windy city, and it did deliver on its name, but nothing could stop the sun-deprived Norwegian students from going outside to soak up some rays.

-

-

Sunset at the beach.

-

-

Students at Lions head. IC: Håvard Vrålstad

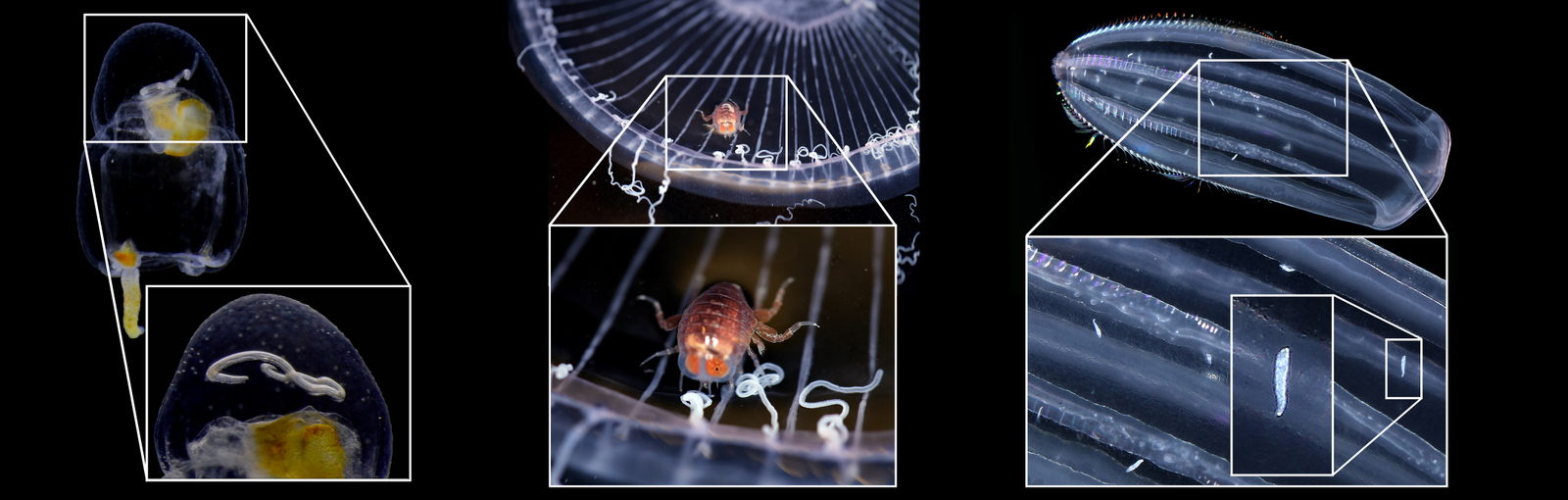

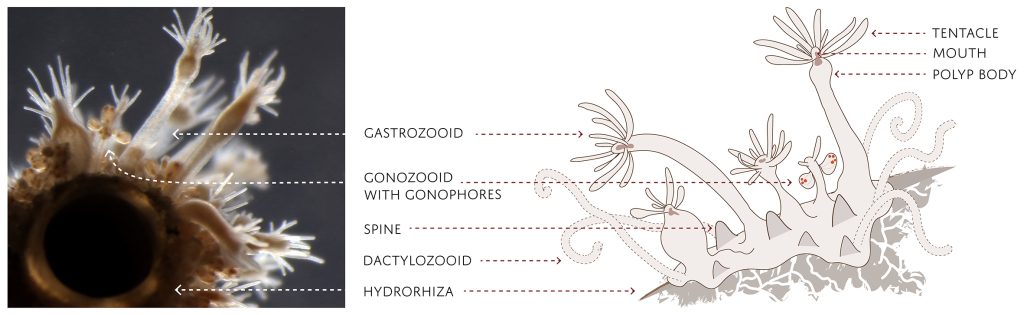

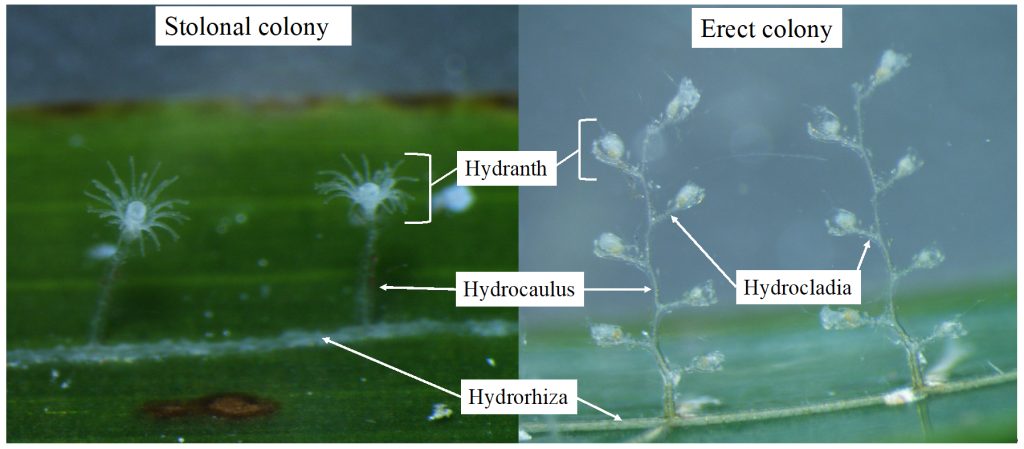

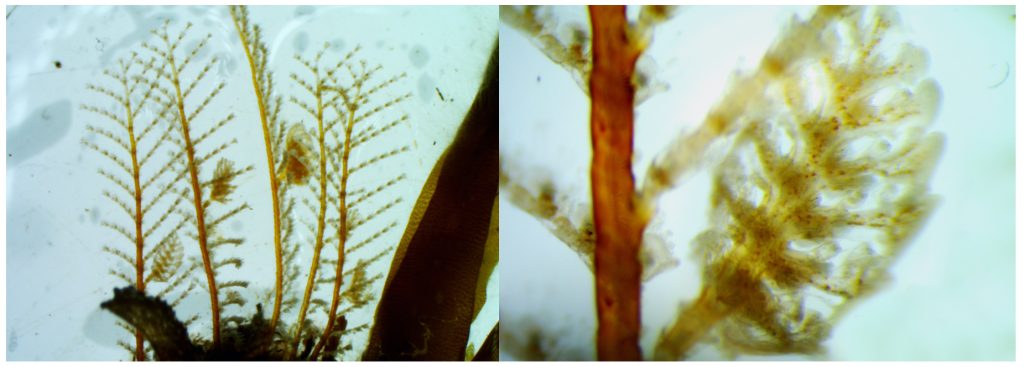

The third day was Hydrozoa day 1, a topic dear to our hearts and it was taught by our own MSc supervisor Luis Martell. Some of us were a bit tired this day because we decided to climb Lion’s head mountain before the workshop started to see the sunrise.

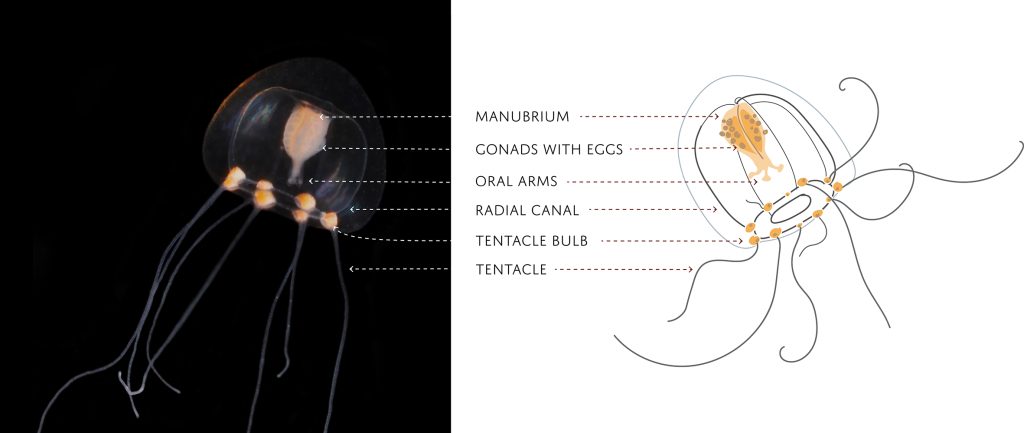

But this did not stop us from eagerly working with the preserved hydrozoan samples we got to look at. We identified all hydromedusae and siphonophores with the help of a stereomicroscope:

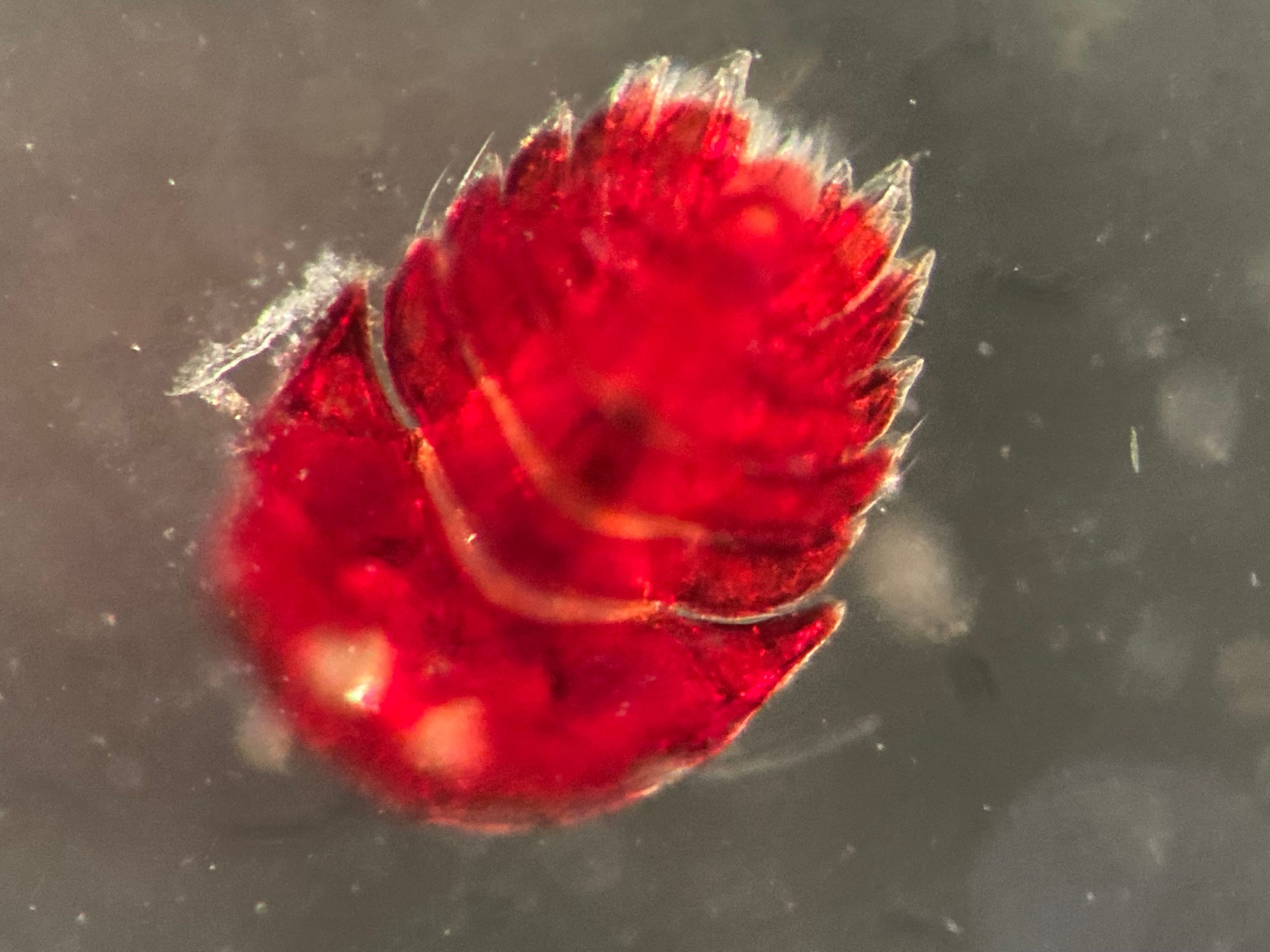

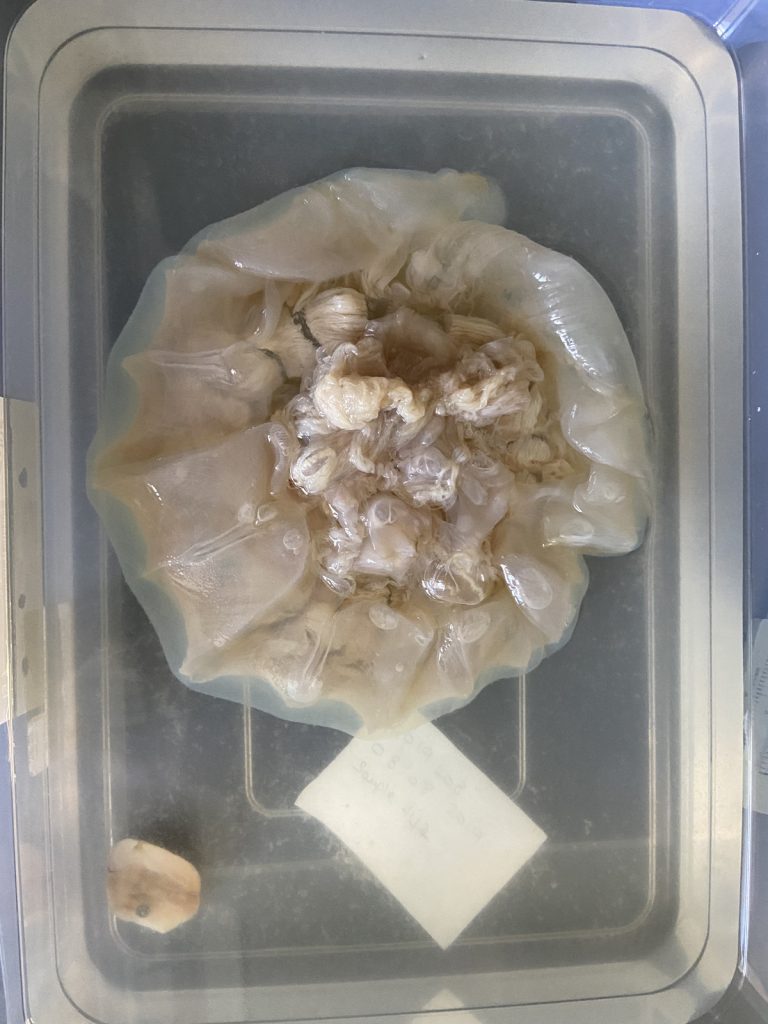

A dissected carybdeid cubozoan jellyfish. IC: Håvard Vrålstad

Day four was box jellies (Cubozoa) day, a class neither of us was very familiar with. So we were excited to learn about these unknown and sometimes dangerous animals.

Luckily the animals were less deadly when preserved and we could therefore touch them while identifying them.

This day ended early so we took the opportunity to get down to Simon’s Town were we spent the rest of the day looking at the local penguins and wildlife at the beach.

A snapshot of the fauna we observed at Simon’s Town. IC: Vincent McDaniel

On our last day, we were introduced to the alien world of siphonophores by our own Aino Hosia. These animals are close to Håvards heart (if you ask him on a good day).

-

-

Fig 7. Anterior nectophores of a representative of genus Sulculeolaria (7a)

-

-

and Chelophyes (7b). IC: Håvard Vrålstad

They were a nice ending to an awesome workshop, and we can honestly say now that our interest for jellyfish has grown, and we look forward to seeing even more of them in the future.

On February 19th the vacation/business trip was unfortunately over for Vetle and Vincent and they had to pack their bags and prepare to leave Cape Town and head home to Bergen, while the “slightly” more fortunate Håvard stayed behind in the windy city to enjoy a few more days of leisure.

Participants and teachers at the jellyfish workshop. IC: Anne Gro Vea Salvanes

We want to thank PRIMALearning for arranging the workshop, the University of the Western Cape for hosting and providing us with samples to work with, the Iziko Museum of South Africa for the location as well as providing refreshments, and to the University of Bergen for arranging accommodations. Also, a very special thanks to all the lecturers who presented and were very patient with us during the lab work.

-Vetle, Vincent, and Håvard

Are you interested in becoming a master student in marine biology at the University Museum of Bergen? Information about available projects can be found here (more will be added soon!):

Marine Masters at the University Museum of Bergen

– available thesis topics in marine biodiversity