This adventure started 26 years ago, when two Norwegian benthos researchers (Torleiv Brattegard from University of Bergen and Jon-Arne Sneli from the University in Trondheim) teamed up with three Icelandic benthos specialists (Jörundur Svavarsson and Guðmundur V. Helgasson from University of Iceland and Guðmundur Guðmundsson from the Natural History Museum of Iceland) to study the seas surrounding the volcanic home of the Nordic sages. 19 cruises and 13 years later – and not least lots of exciting scientific findings and results the BioICE program was finished.

This adventure started 26 years ago, when two Norwegian benthos researchers (Torleiv Brattegard from University of Bergen and Jon-Arne Sneli from the University in Trondheim) teamed up with three Icelandic benthos specialists (Jörundur Svavarsson and Guðmundur V. Helgasson from University of Iceland and Guðmundur Guðmundsson from the Natural History Museum of Iceland) to study the seas surrounding the volcanic home of the Nordic sages. 19 cruises and 13 years later – and not least lots of exciting scientific findings and results the BioICE program was finished.

But science never stops. New methods are developed and old methods are improved – and the samples that were stored in formalin during the BioICE project can not be used easily for any genetic studies. They are, however, very good for examinations of the morphology of the many invertebrate species that were collected, and they are still a source of much interesting science.

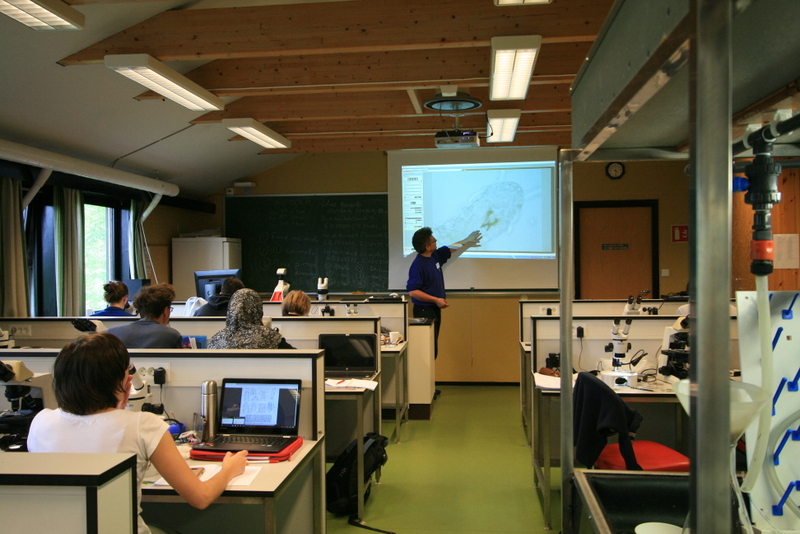

Participants of the IceAGE workshop. Photo: Christian Bomholt (www.instagram.com/mcb_pictures)

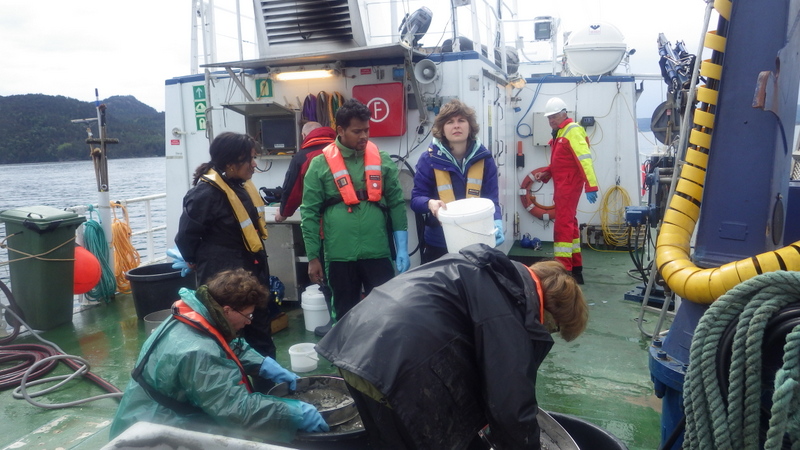

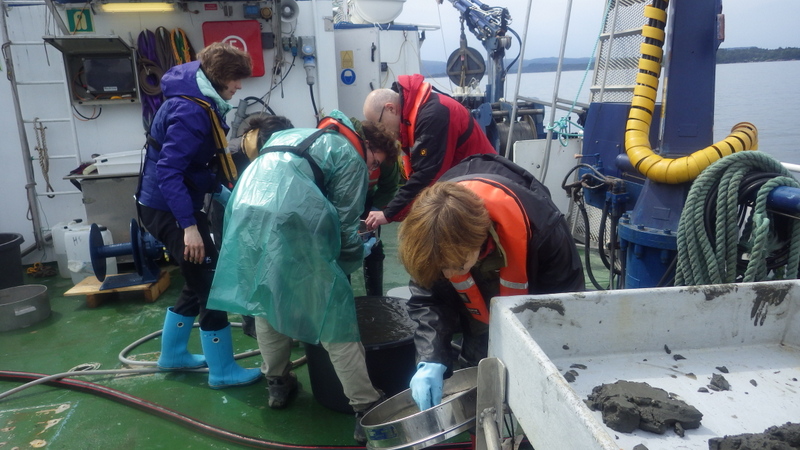

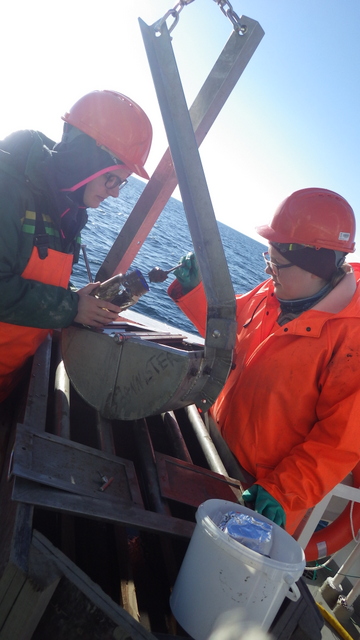

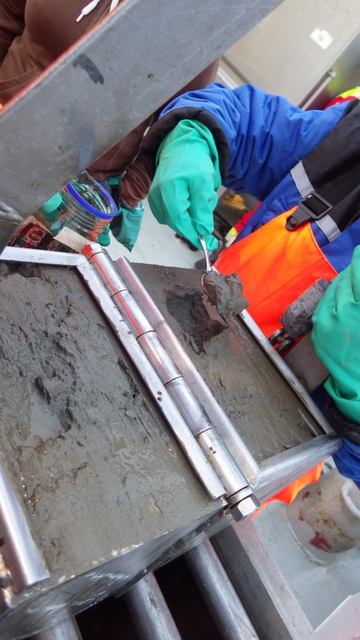

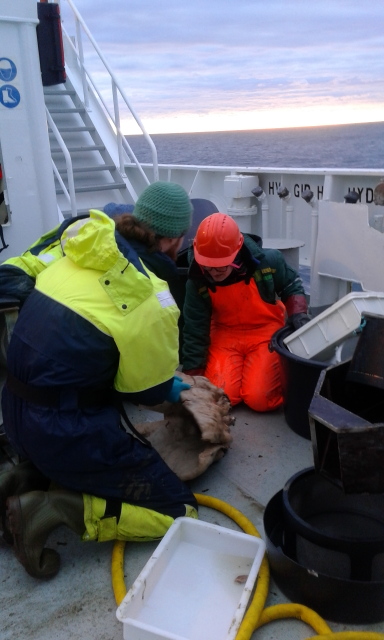

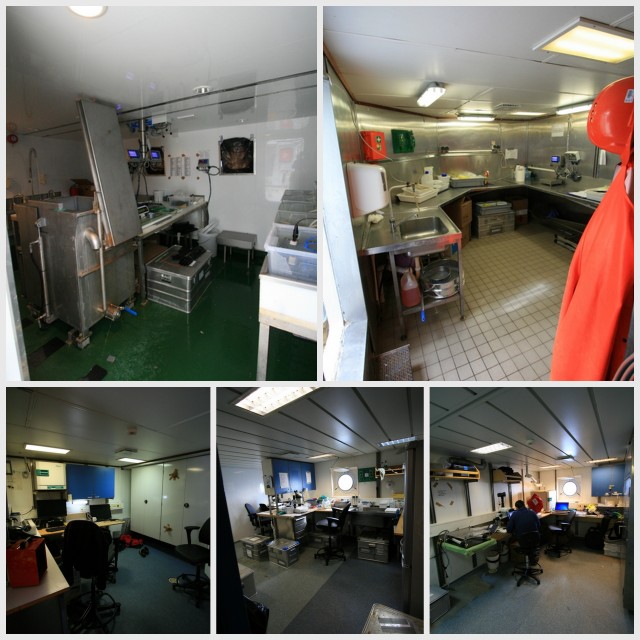

The dream about samples that could be DNA-barcoded (and possibly examined further with molecular methods) lead to a new project being formed – IceAGE. A large inernational collaboration of scientists organised by researchers from the University of Hamburg (and still including researchers from both the University of Iceland and the University of Bergen) have been on two cruises (2011 and 2013) so far – and there is already lots of material to look at!

-

-

Ready to start the workshop! Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

The beaver was here! Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

Ed found the bison! Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

What way should we take? Amphipodologists out of their natural habitat? Photo: AH Tandberg

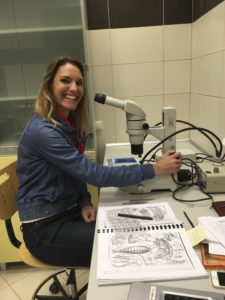

This week many of the researchers connected with the IceAGE project have gathered in Spała in Poland – at a researchstation in woods that are rumoured to be inhabited by bison and beavers (we didn´t see any, but we have seen the results of the beavers work). Some of us have discussed theories and technical stuff for the papers and reports that are to come from the project, and then there are “the coolest gang” – the amphipodologists. 10 scientists of this special “species” have gathered in two small labs in the field-station, and we have sorted and identified amphipods into the wee hours.

-

-

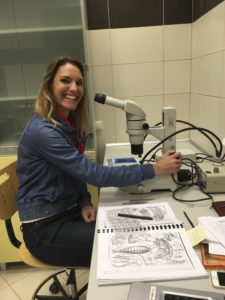

Lauren and Anne-Nina hard at work. Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

Wims microscope after a sample is done.. Photo: Christian Bomholt (www.instagram.com/mcb_pictures)

-

-

Lauren after getting the identification right. Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

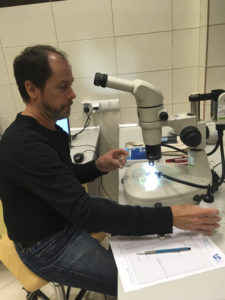

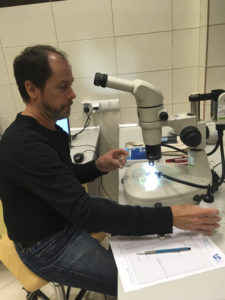

Ed at work with a nice sample. Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

Lauren examines the specimen while Anne-Nina and Tammy checks the literature. Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

“the Anne-table” in the amphipod lab. Photo: Christian Bomholt (www.instagram.com/mcb_pictures)

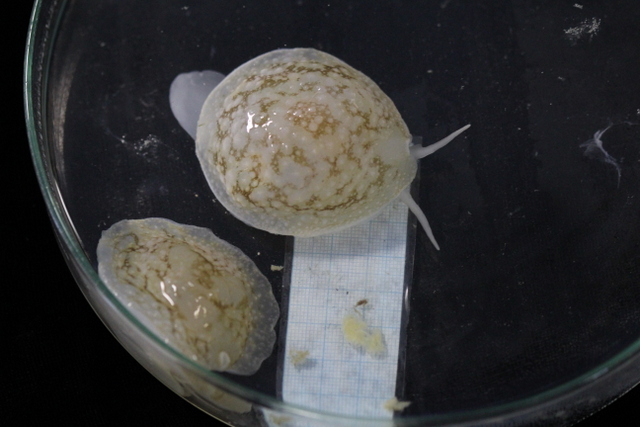

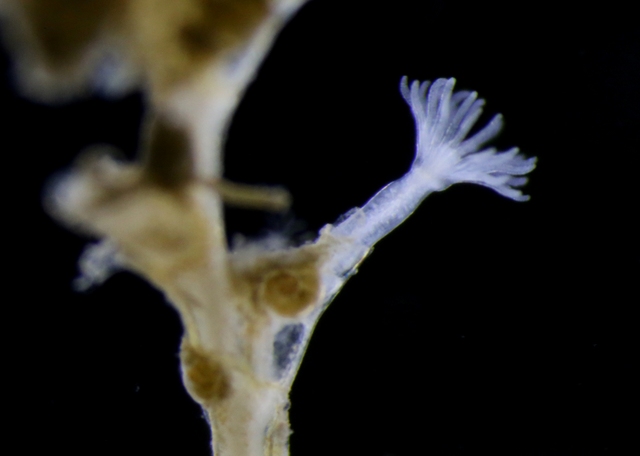

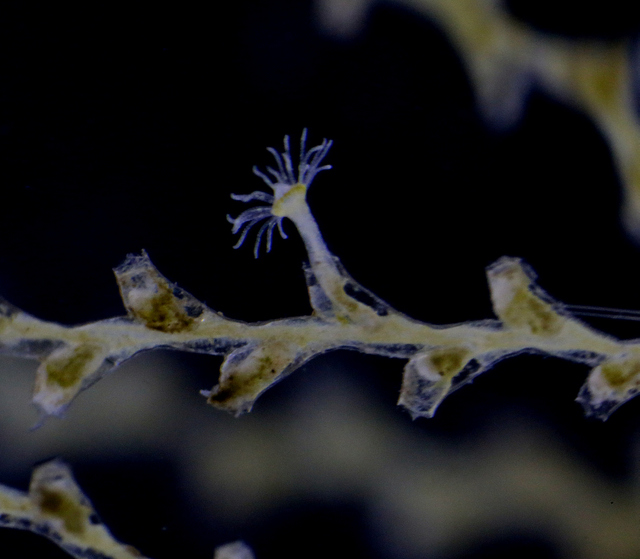

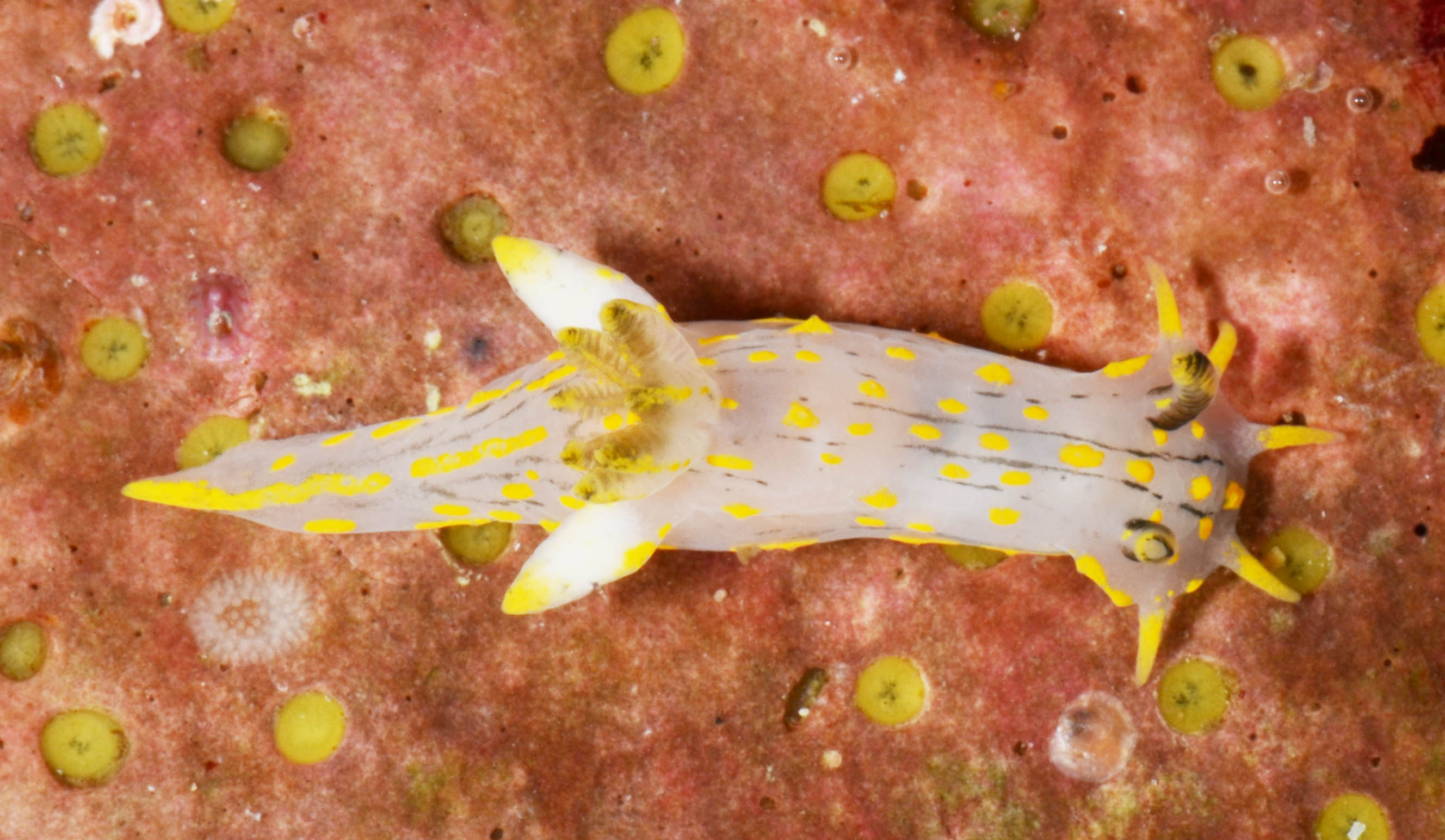

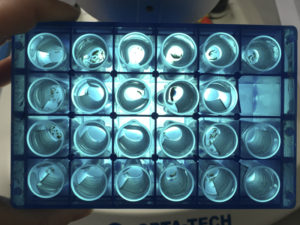

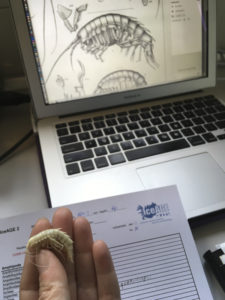

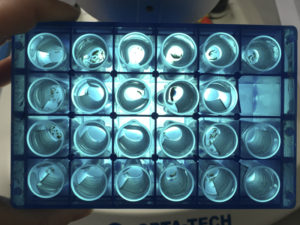

It is both fun and educational to work together. Everybody have their special families they like best, and little tricks to identify the difficult taxa, and so there is always somebody to ask when you don´t find out what you are looking at. Between the stories about amphipod-friends and old times we have friendly fights about who can eat the most chocolate, and we build dreams about the perfect amphipodologist holiday. Every now and then somebody will say “come look at this amazing amphipod I have under my scope now!” – we have all been treated to species we have never seen before, but maybe read about. We also have a box of those special amphipods – the “possibly a new species”- tubes. When there is a nice sample to examine, you might hear one of the amphipodologist hum a happy song, and when the sample is all amphipods but no legs or antennae (this can happen to samples stored in ethanol – they become brittle) you might hear frustrated “hrmpfing” before the chocolate is raided.

-

-

A large amphipod comes out of the jar! Photo: Christian Bomholt (www.instagram.com/mcb_pictures)

-

-

Cleippides quadricuspis. Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

Amphipods sorted and identified. Photo: AH Tandberg

Isopodologists (Martina and Jörundur) visiting the amphipodologists… Photo: AH Tandberg

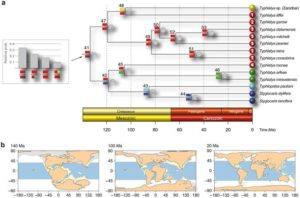

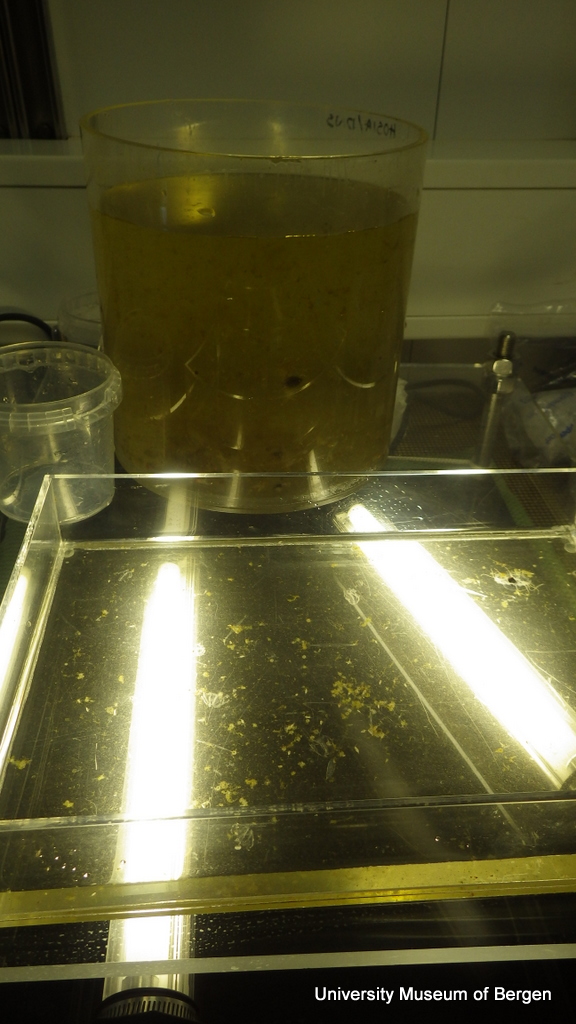

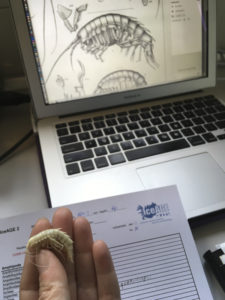

The samples from IceAGE are all stored in ethanol. This is done to preserve the DNA for molecular studies – studies that can give us new and exciting results to questions we have thought about for a long time, and to questions we maybe didn´t even know we needed asking. We can test if what looks like the same species really is the same species, and we can find out more about the biogeography of the different species and communities.

The geographical area covered by IceAGE borders to the geographical area covered by NorAmph and NorBOL, and it makes great sense to collaborate. This summer we will start with comparing DNA-barcodes of amphipods from the family Eusiridae from IceAGE and NorAmph. They are as good a starting-point as any, and they are beautiful (Eusirus holmii was described in the norwegian blog last summer).

-

-

The field-station is ready for easter. Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

The coolest easter-chickens in Spala. Photo: AH Tandberg

-

-

Easter-prepared coffee! Photo: AH Tandberg

Happy easter from all the amphiods and amphipodologists!

Anne Helene

Literature:

Brix S (2014) The IceAGE project – a follow up of BIOICE. Polish Polar Research 35, 1-10

Dauvin J−C, Alizier S, Weppe A, Guðmundsson G (2012) Diversity and zoogeography of Ice−

landic deep−sea Ampeliscidae (Crustacea: Amphipoda). Deep Sea Research Part I: 68: 12–23.

Svavarsson J (1994) Rannsóknir á hryggleysingjum botns umhverfis Ísland. Íslendingar og hafiđ.

Vísindafélag Íslendinga, Ráđstefnurit 4: 59–74.

Svavarsson J, Strömberg J−O, Brattegard T (1993) The deep−sea asellote (Isopoda,

Crustacea) fauna of the Northern Seas: species composition, distributional patterns and origin. Journal of Biogeography 20: 537–555.