When we think about what drives the ecosystems, much of the initial responsibility is put on the sunlight. This is mainly because of the photosynthesis, and thus the basic pieces of almost all food-webs, but light is also important for the animals. Many animals use visual cues to find food, and whether you search for food or do not want to become food, the presence (or absence) of light will help you.

Seawater is a pretty good stopper of light. We don’t need to dive far down before we are in what we consider a dark place, and less and less light finds its way the deeper we come. We tend to call the depths between 200 and 1000 m “the twilight zone”: most light stops way before 200m and the last straggling lumens give up at 1000m.

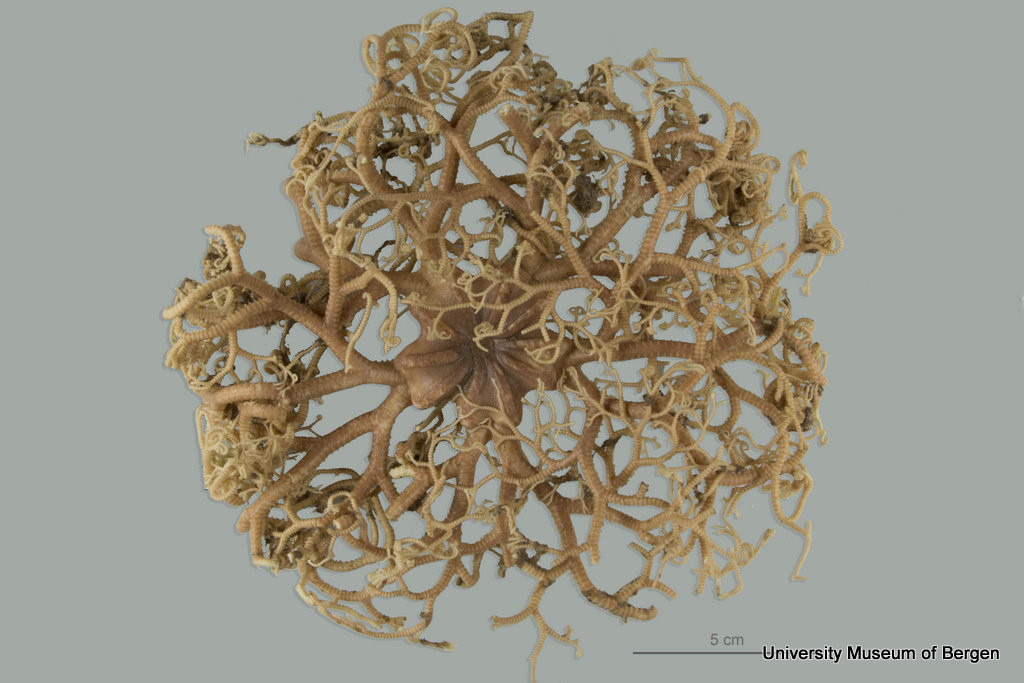

Most places on earth has a daily division between a dark and a light period: night and day. This is the ultimate reason for what is often called “the largest motion on earth”: Millions of zooplankton hide out in the darker parts of the water column during the day, and then move up to feed on the plants living in the light-affected parts of the water during the night (when predators will have a hard time seeing them). This daily commute up and down is called Diel Vertical Migration (DVM).

Themisto sp among the many smaller particles. (The light in this picture is from a flash). Photo: Geir Johnsen, NTNU

But what about the waters north of the polar circle? These areas will for some time during the winter have days when the sun stays under the horizon the entire day – this is “the Dark time” (Mørketid). At higher latitudes, there will be several days, or even weeks or months when the sun is so far below the horizon that not even the slightest sunset-glow is visible at any time. In this region, we have long thought that the Dark time must be a dead or dormant time.

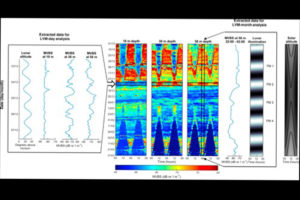

We could not have been more wrong! It turns out that during the polar night, the DVM moves from being on a 24 hr cycle (sunlight-induced), to a 24.8 hour cycle! What is now the driver? The moon !(The lunar day is 24.8 hrs). Another thing that shows us that the moon must give strong enough light that predators can hunt by it, is that every 29.5 days most of the zooplankton sinks down to a depth of 50m: this falls together with the moon being full. Researchers have started to call this LVM (Lunar-day Vertical Migration) to show the difference to the “normal” DVM. There are of course lots of complicated details such as the moons altitude above the horizon and its phase that influences the LVM, but in general we can say that during the polar night (the Very Dark time), the “day” as decided by light has become slightly longer than normal.

Themisto – the werewolf. Note that the whole head is dominated by eyes – this is a visual hunter! Photo: Geir Johnsen, NTNU

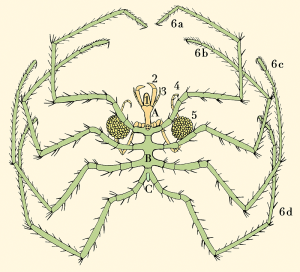

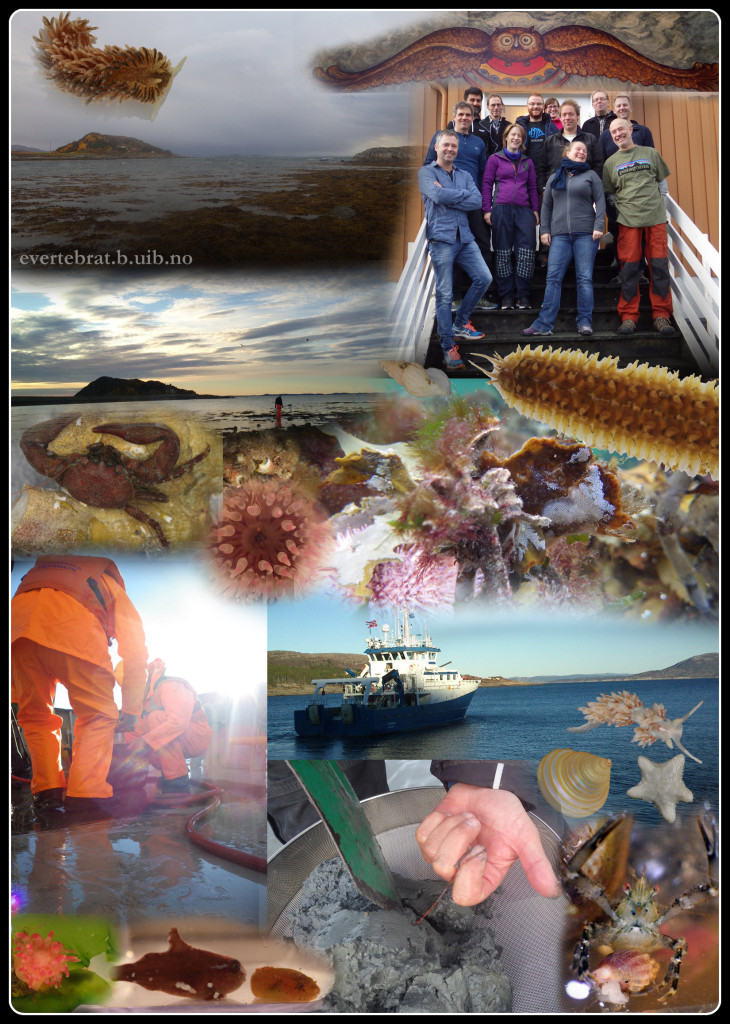

Some of the larger animals taking part in the LVM are the amphipods Themisto abyssorum and Themisto libellula. They are hunters – so their reason to migrate up in the water column is not the plants, but the animals eating the plants; their favourite food are copepods of the genus Calanus. These are nice and quite energy-rich small crustaceans that eat the microscopic plants in the upper water column. We have sampled both Themisto-species in the middle of the winter (january), and their guts were filled to the brim with Calanus, so we know that they continue hunting by moon-light. They are such voracious hunters that some researchers have started to call them marine werewolves: the moonlight transforms them from sedate crustaceans to scary killers…

But, if they are the hunters, why do they spend so much time in the deep and dark during the lighter parts of the day? The hunters are of course also hunted. Fish such as polar cod (Boreogadus saida), birds such as little auk (Alle alle) and various seals like to have their fill of the Themisto species. So – life has its ups and downs, and the dance of hunter and hunted continues into the dark polar night…

Anne Helene

Literature:

Berge J, Cottier F, Last KS et al (2009) Diel vertical migration of Arctic zooplankton during the polar night. Biology Letters 5, 69-72.

Berge J, Renaud PE, Darnis G et al (2015) In the dark: A review of ecosystem processes during the Arctic polar night. Progress in Oceanography 139, 258-271.

Kintisch E (2016) Voyage into darkness. Science 351, 1254-1257

Kraft A, Berge J, Varpe Ø, Falk-Petersen S (2013) Feeding in Arctic darkness: mid-winter diet of the pelagic amphipods Themisto abyssorum and T. libellula. Marine Biology 160, 241-248.

Last KS, Hobbs L, Berge J, Brierley AS, Cottier F (2016) Moonlight Drives Ocean-Scale Mass Vertical Migration of Zooplankton during the Arctic Winter. Current Biology 26, 244-251.