In the last months, our project NorHydro has been very busy with sampling trips and outreach; we have been collecting hydroids in Southern Norway, presenting our results in festivals, and hunting for hydrozoans inside mythical monsters as well as around Bergen, the project’s hometown. All of these activities sound like a lot of work, and they certainly take a fair amount of time and effort, but the good thing is that NorHydro has never been alone in its quest for knowledge of the marine creatures: on the contrary, this has been the season of collaborations and synergies for our project!

At the end of August, for example, we attended the marine-themed festival Passion for Ocean; where we shared the stand of the University Museum of Bergen with a bunch of colleagues, all working on several kinds of marine creatures, from deep sea worms and sharks to sea slugs and moss-animals. It was a great opportunity to talk to people outside academia (including children!) about our work at the museum, and also to show living animals to an audience that does not venture too often into the sea.

Our stand at the Passion for Ocean festival was incredibly popular with the public – we feel like most of the 5-6000 people who attended P4O must have dropped by to talk to us! Photos: K. Kongshavn and M. Hosøy

Although most of the people in Bergen are familiar with jellyfish, very few of them would know that most jellies are produced by flower-looking animals living in the bottom of the ocean, so the participation of NorHydro was met with a lot of surprise and curiosity. The festival was a big success (you can read a more about the experience in the Norwegian version of the blog), and hopefully we will get the chance to join again next year.

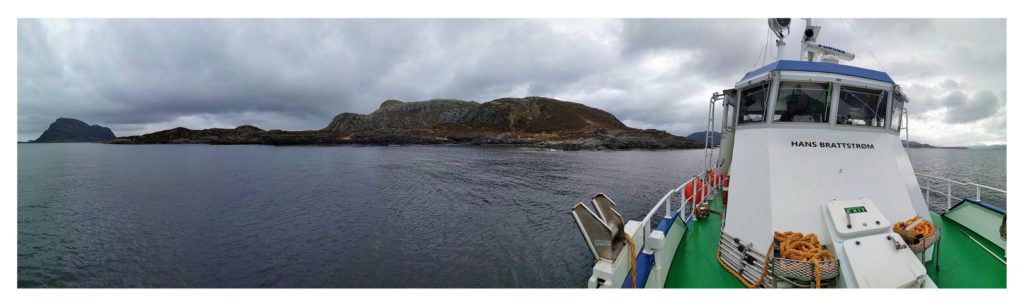

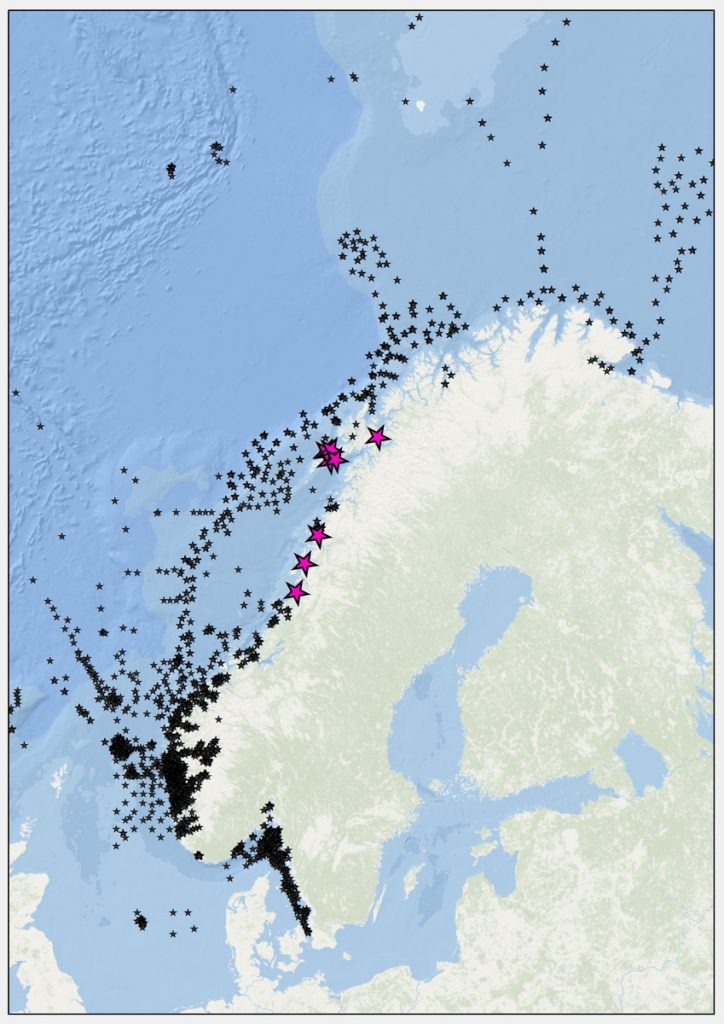

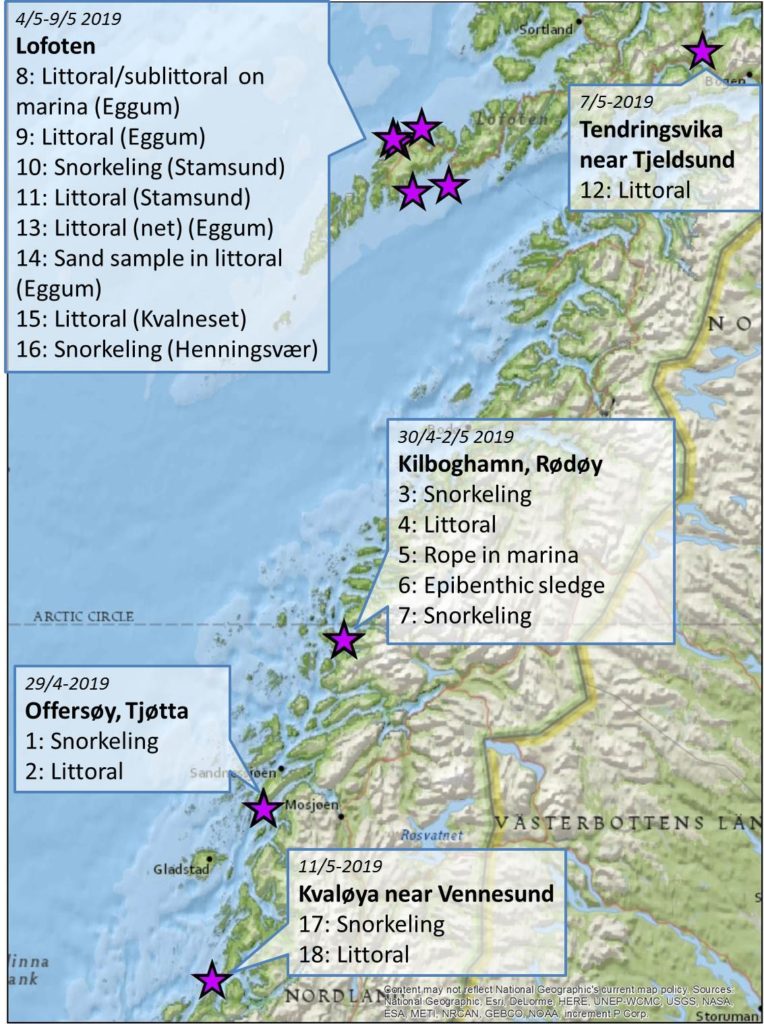

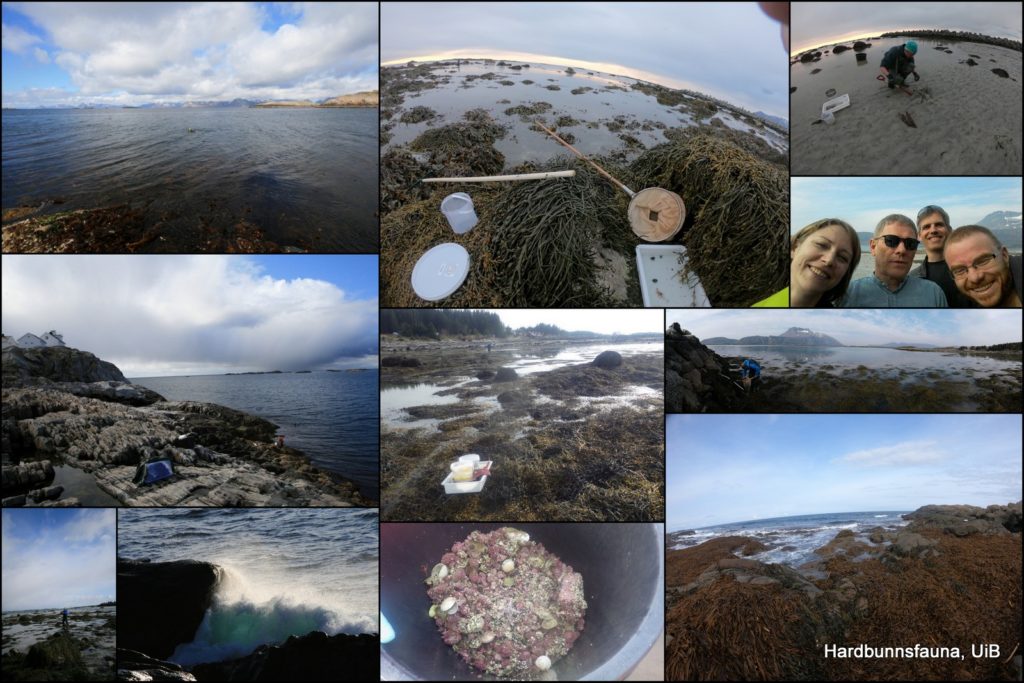

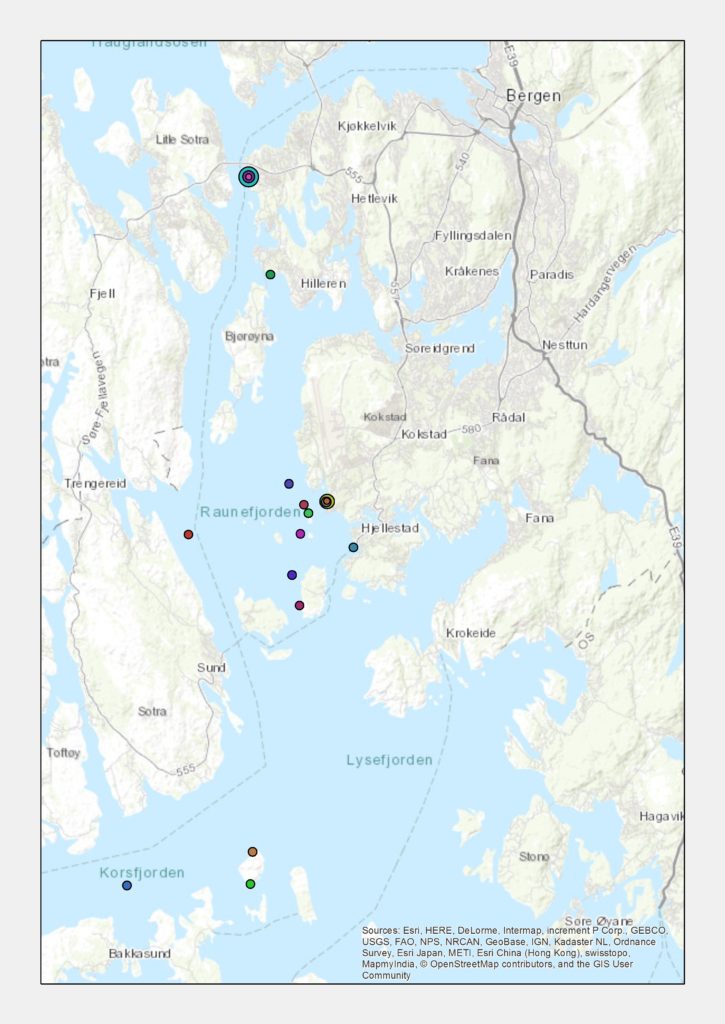

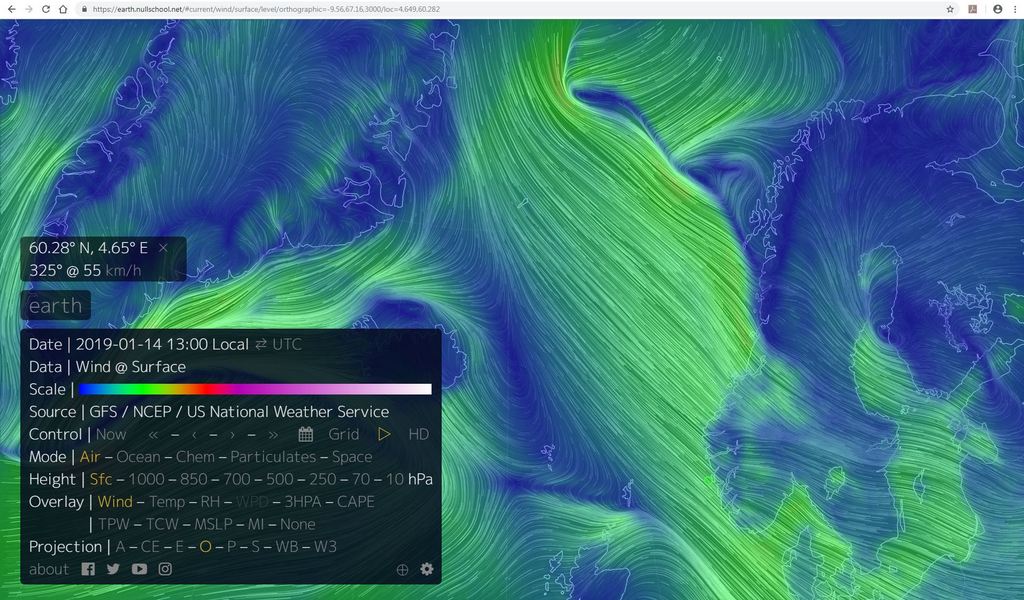

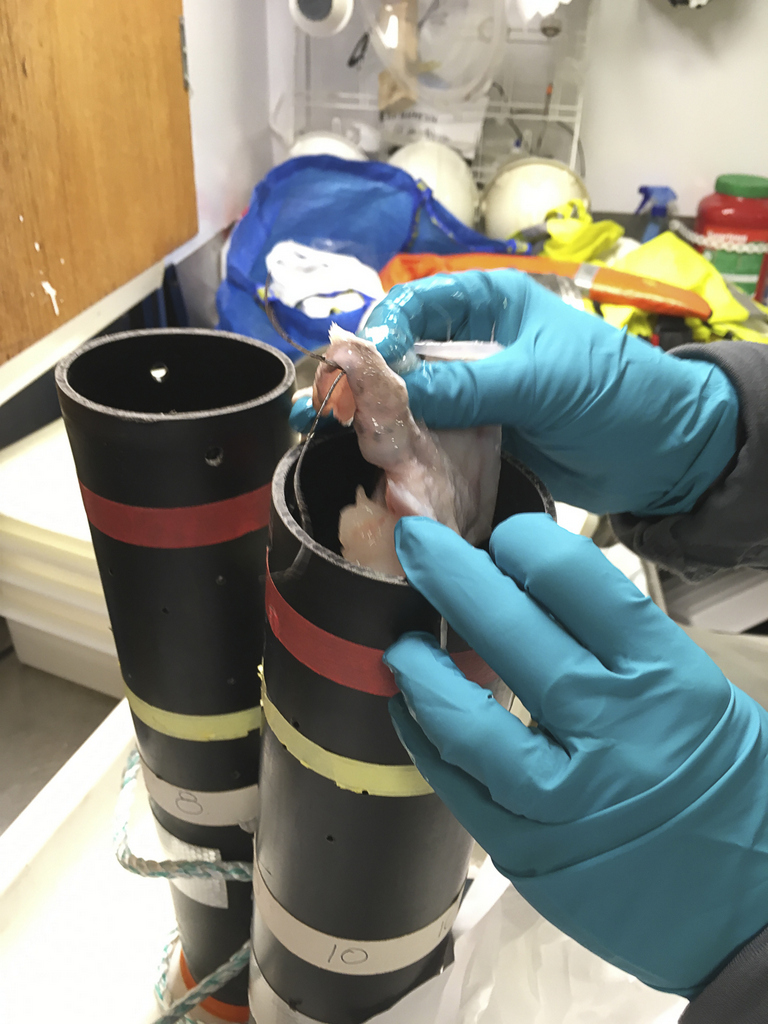

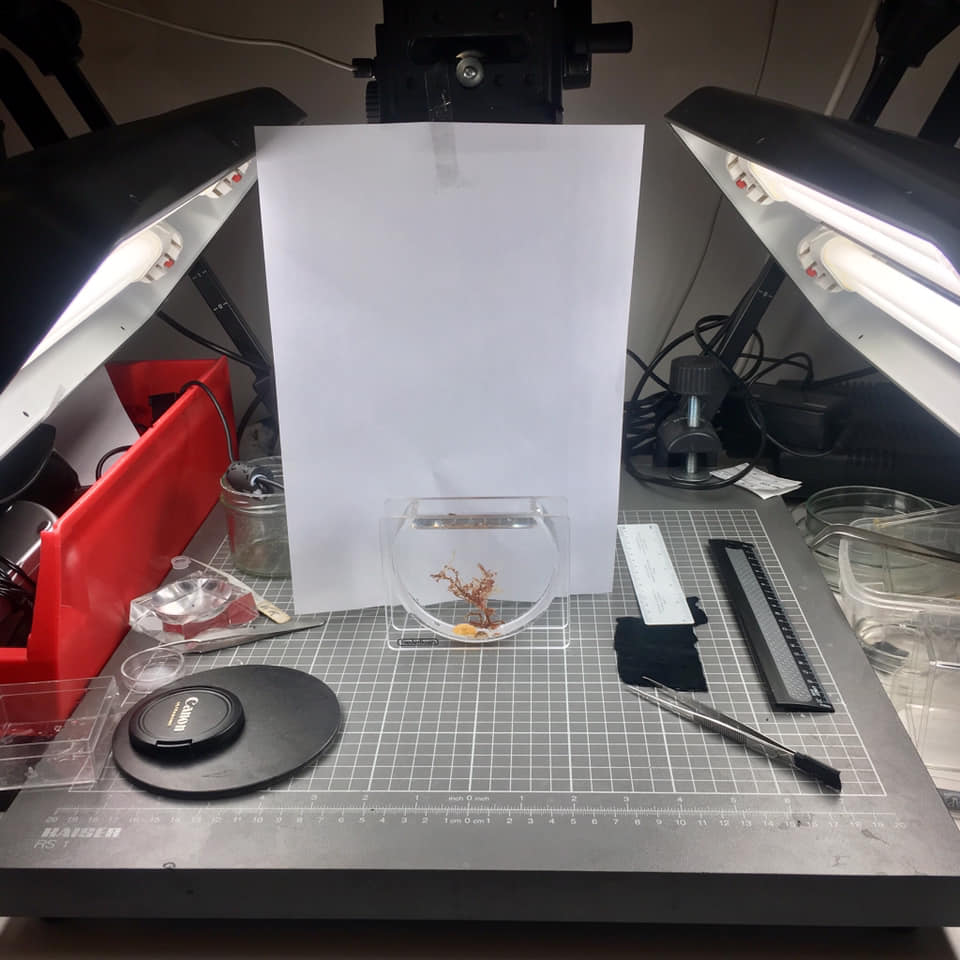

Later on, in September, we set off for a field trip to the northerly area of Saltstraumen, in the vicinity of the Arctic city of Bodø. For this trip NorHydro was again in collaboration with the UMB-based project “Hardbunnfauna” (Jon and Katrine represented the hard-bottom dwelling invertebrate fauna scientists) and also with Torkild Bakken (from NTNU University Museum, with his project “#Sneglebuss”). For me, Saltstraumen was definitely an exciting place to go; the strong currents of Saltstraumen have been the cause of death of too many sailors and seamen in the past, so in the collective mind the area has become some sort of man-eating whirlpool similar to the Mediterranean Charybdis… I don’t get to sample inside a mythological creature very often! Underneath the water though, Saltstraumen is teeming with life.

During this trip, we were prepared to sample in the littoral zone (and we did), but more importantly we were lucky enough to meet several enthusiast citizen and professional scientists that were diving in the area and shared with us some of their observations.

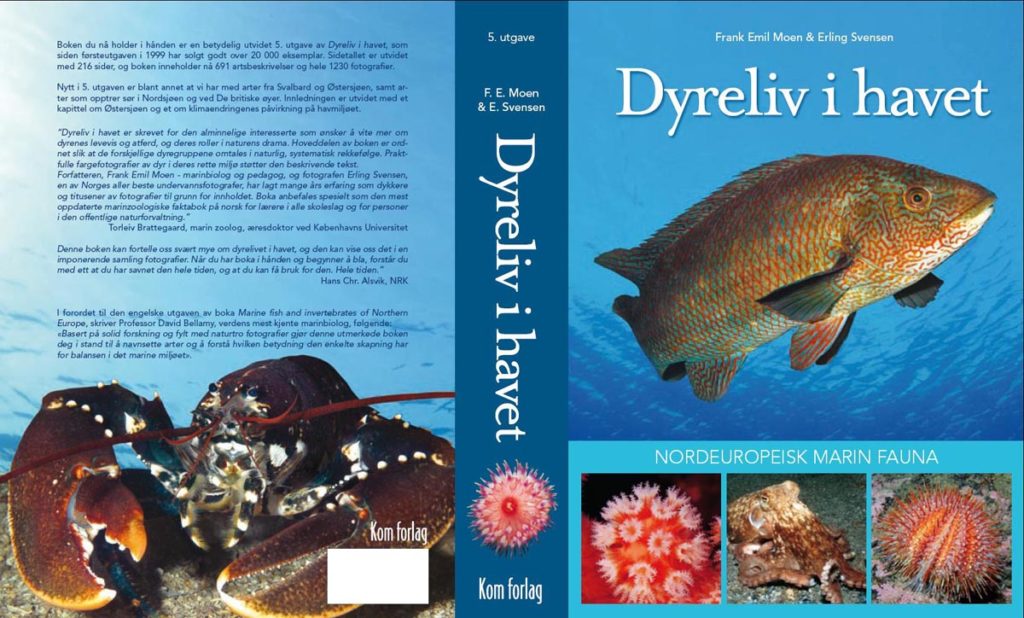

We were treated to extremely nice underwater pictures of invertebrates by Bernard Picton and Erling Svensen, and all the participants in the activities of the local diving club (Saltstraumen Dykkecamp) were very keen in providing us with suggestions, animals, images and impressions that made our sampling trip a total success.

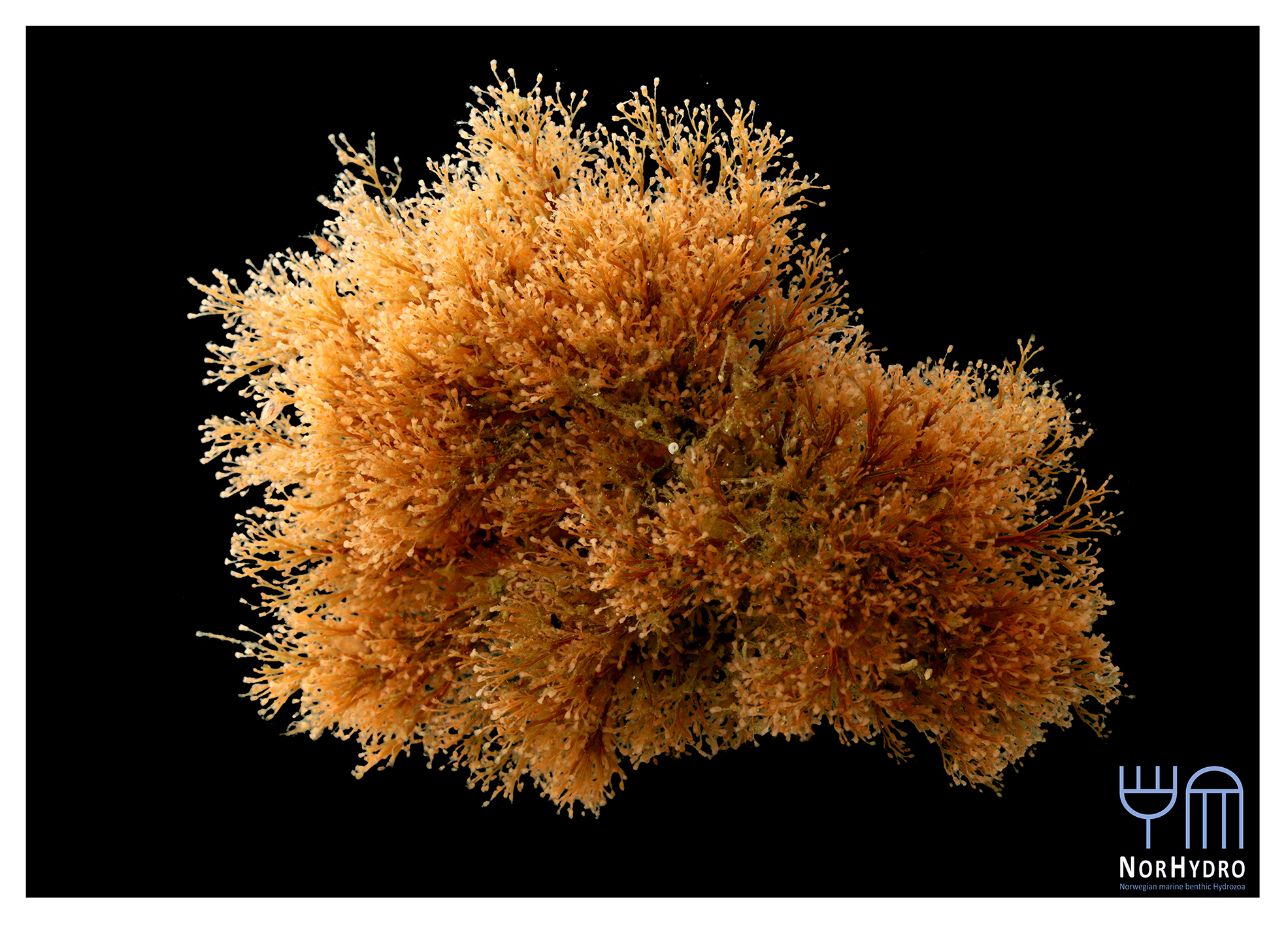

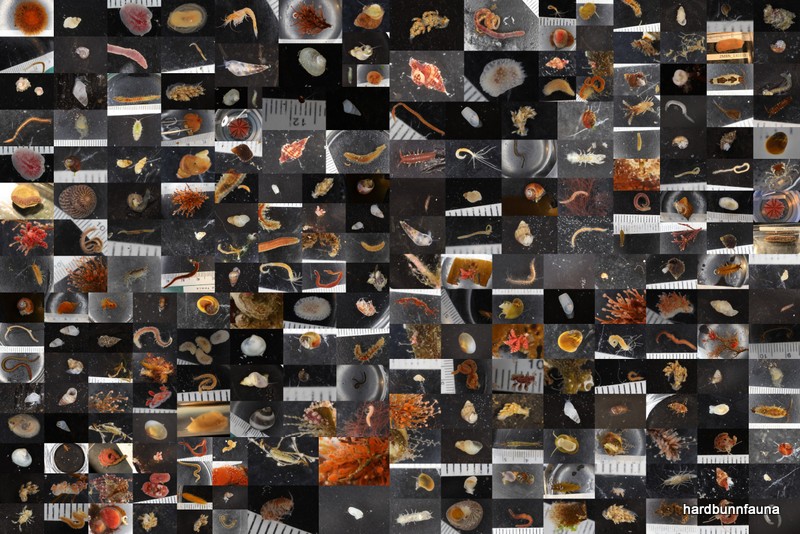

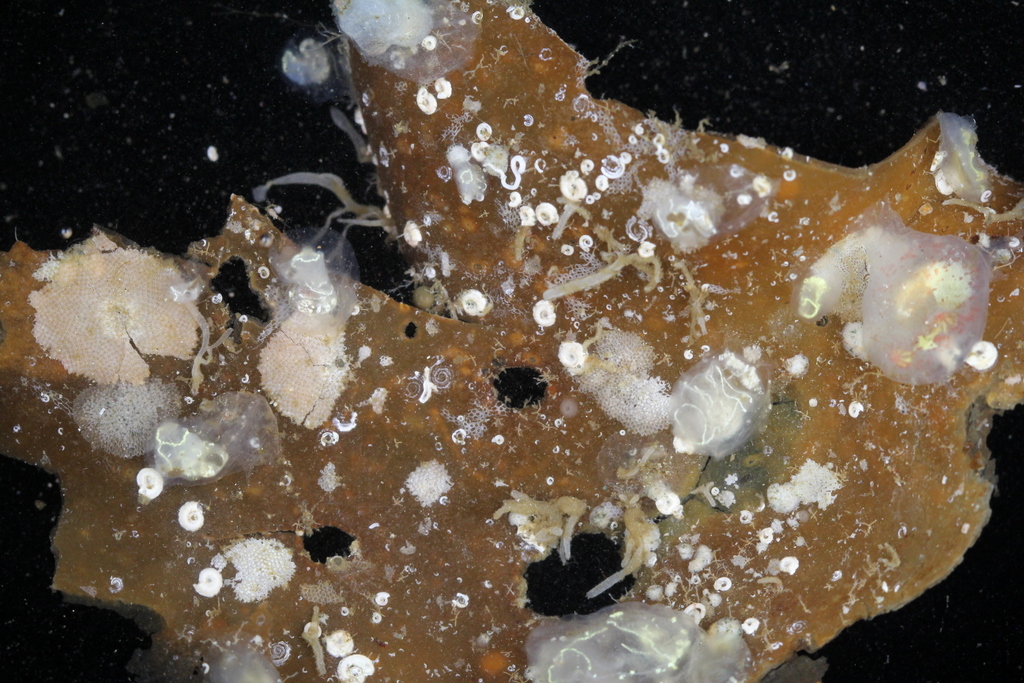

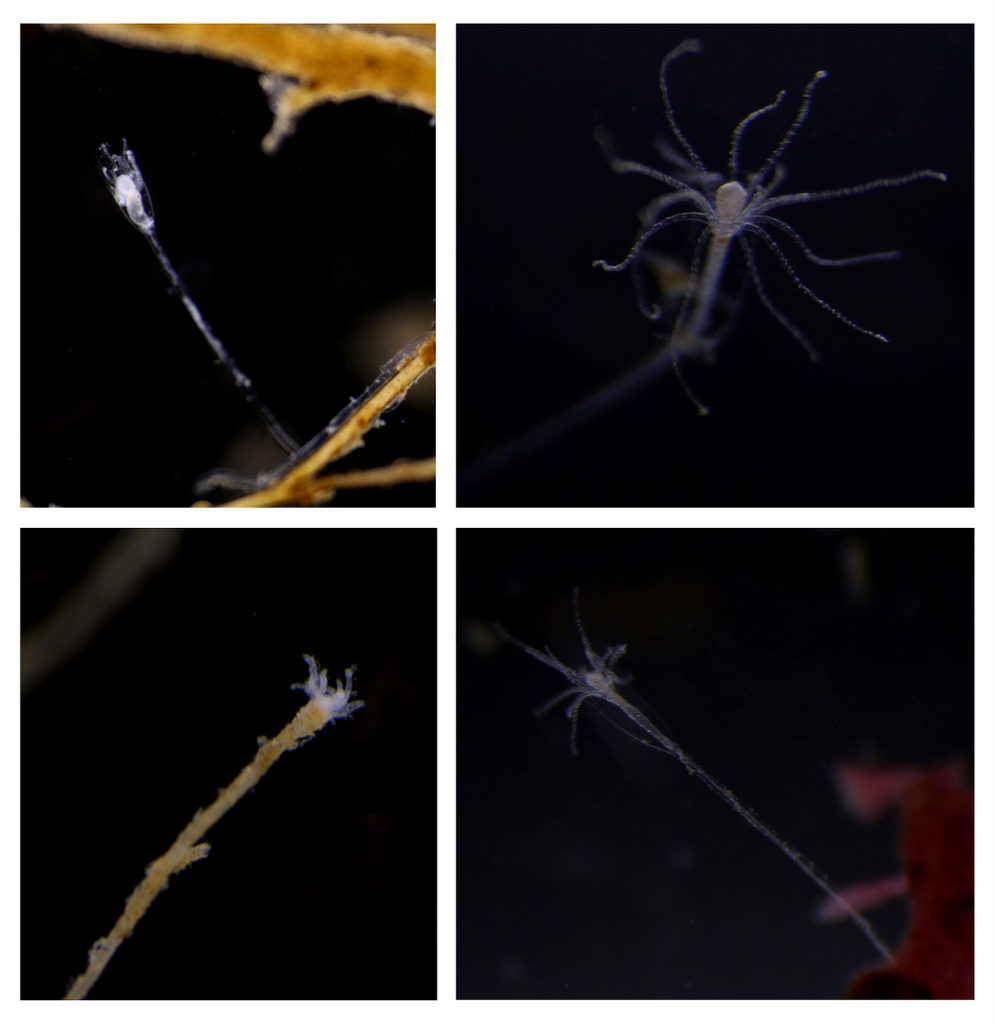

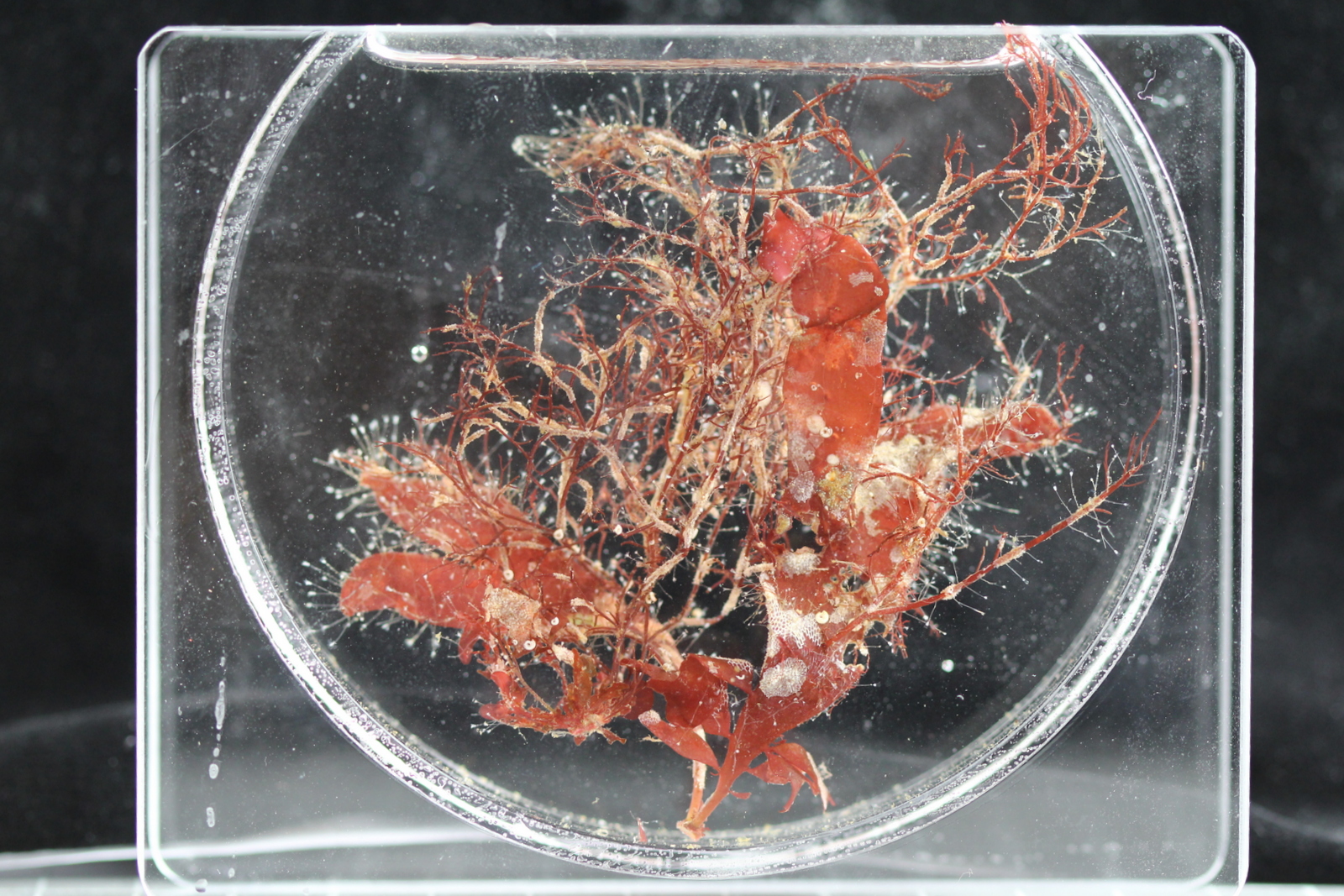

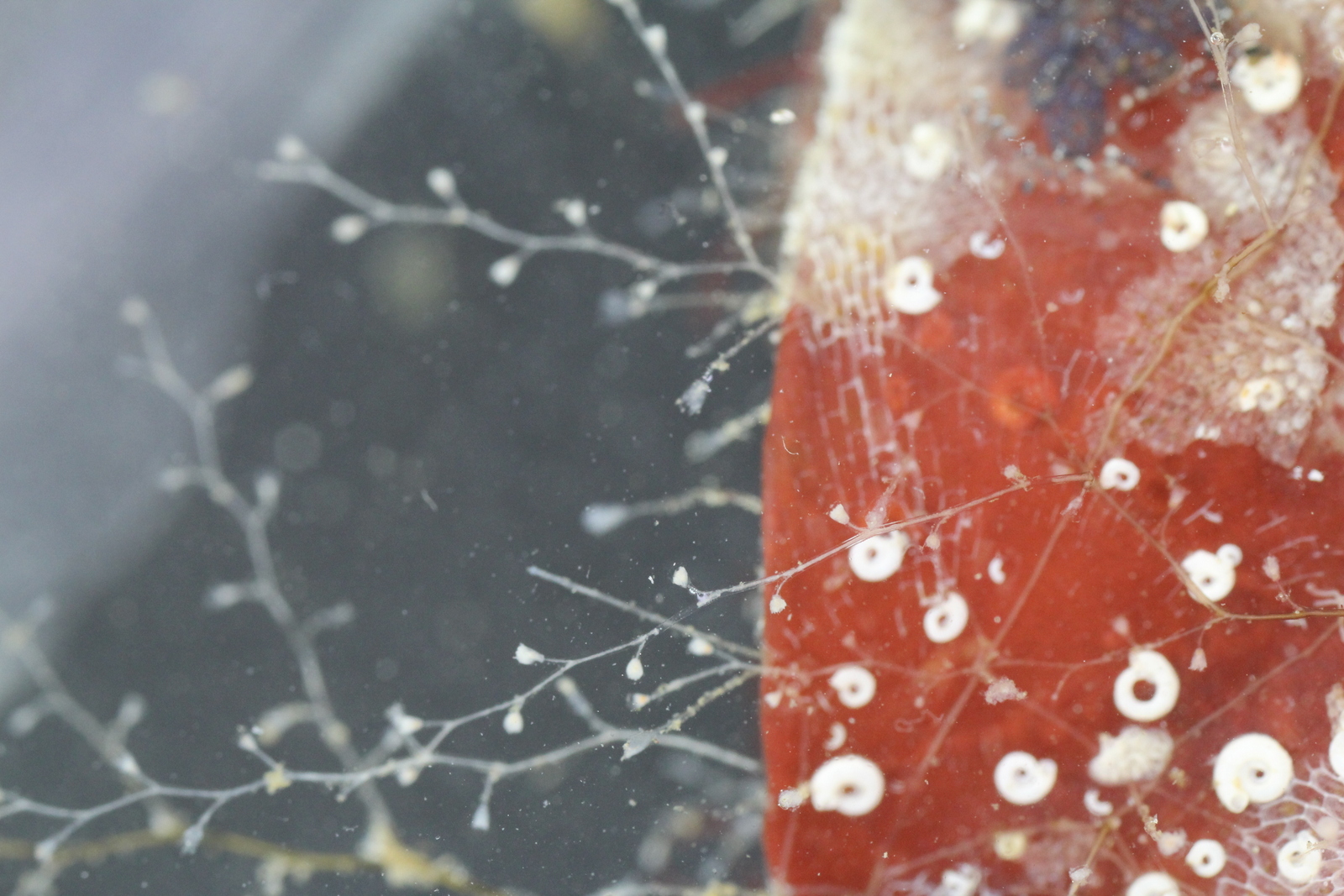

The area was dubbed as a “hydroid paradise” (likely due to the strong currents that favor the development of large hydrozoan colonies), and many new records and even perhaps new species are present in the region.

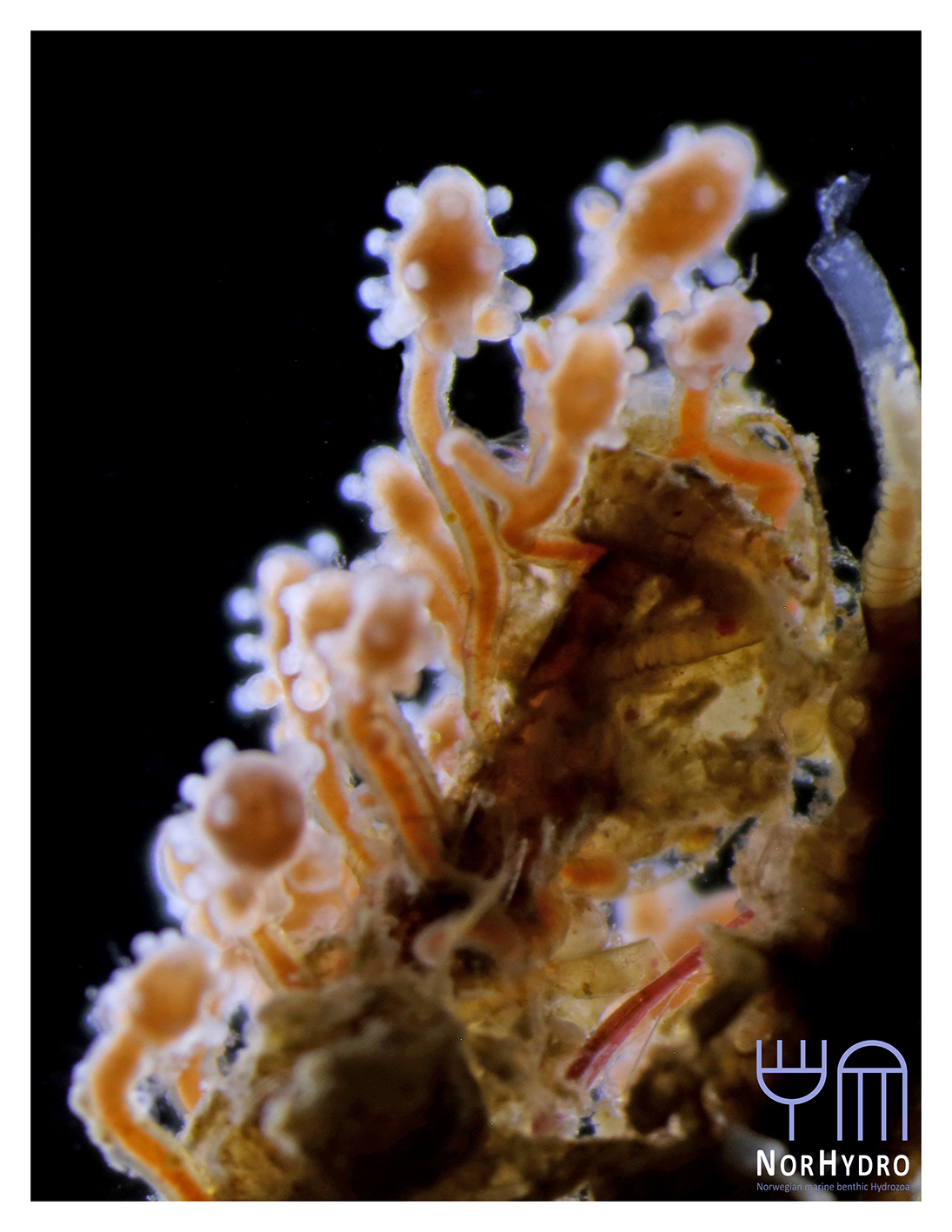

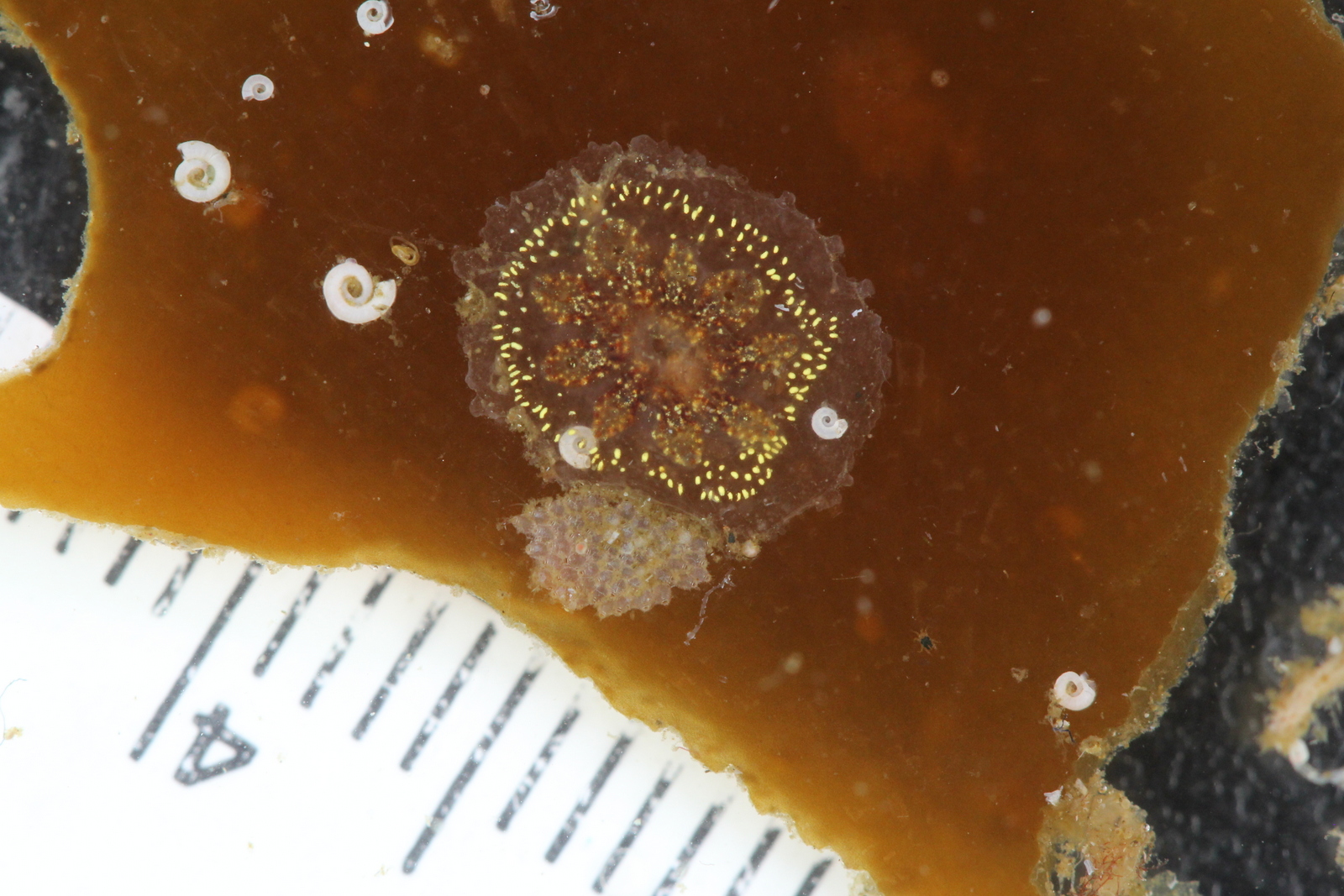

- A colony of Hydractinia growing on the shell of a hermit crab

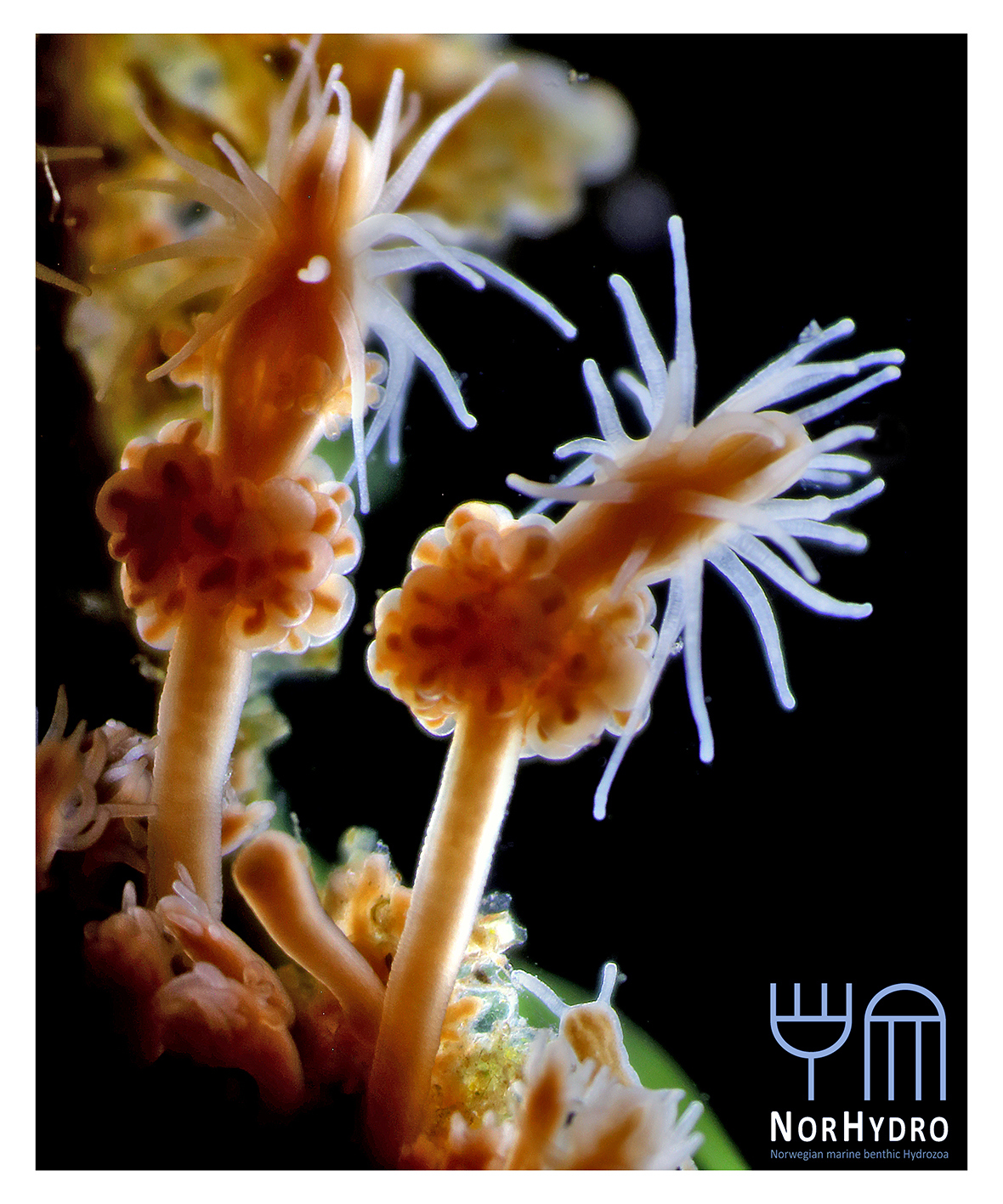

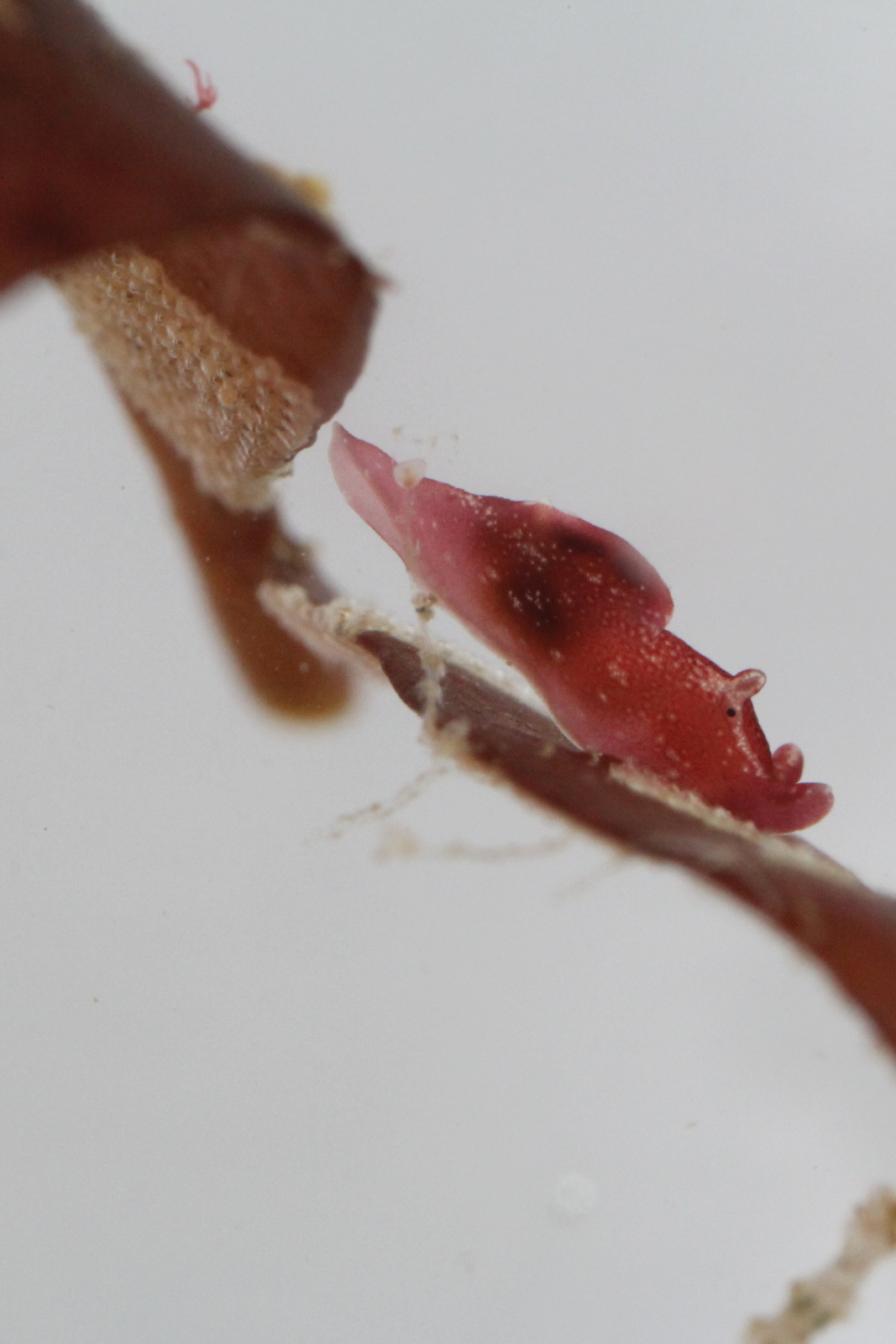

- Large hydroids like Tubularia indivisa provide refuge and food for many other species of invertebrates

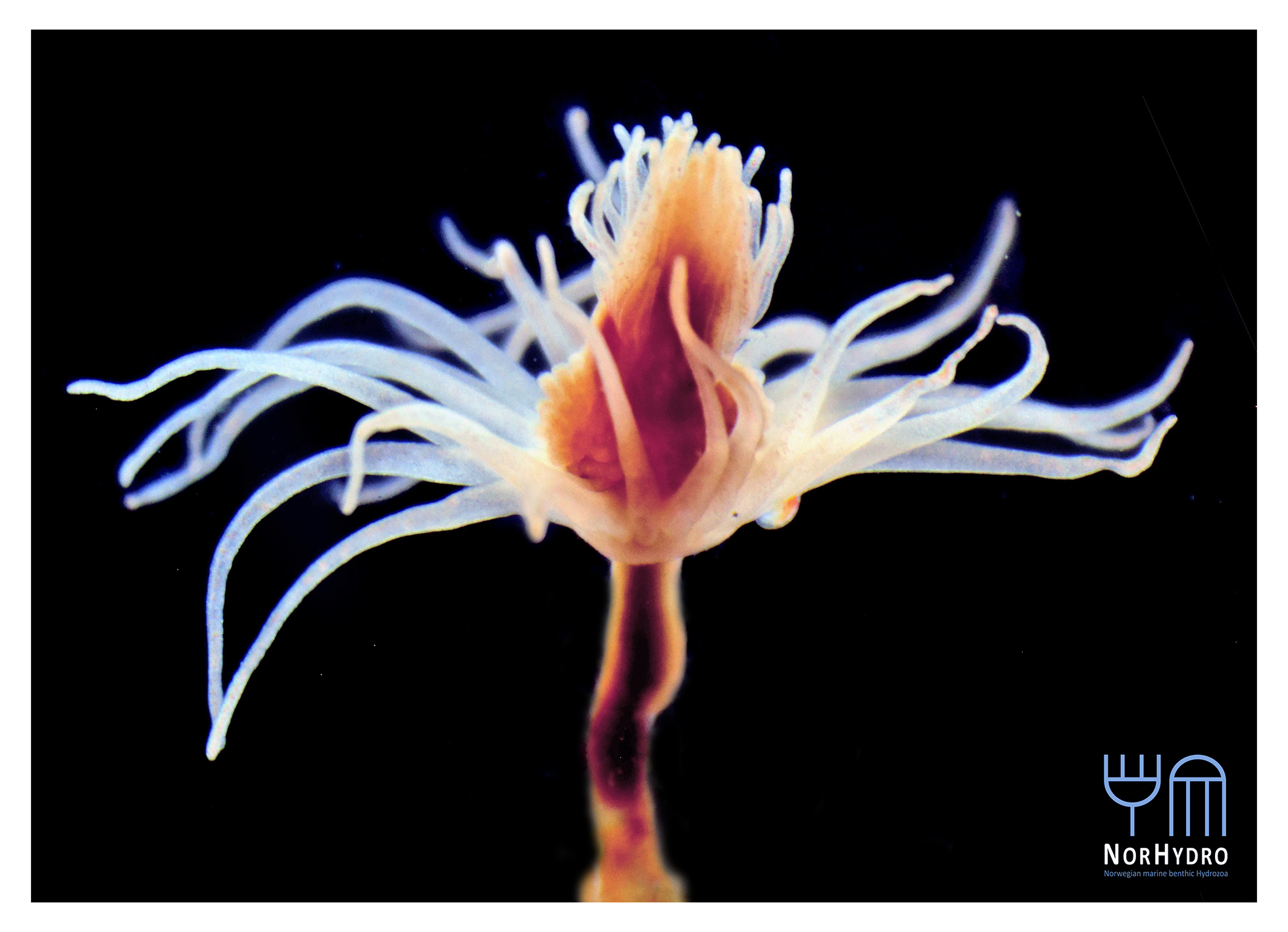

- A medusa of Bougainvillia about to be released from the hydroid colony

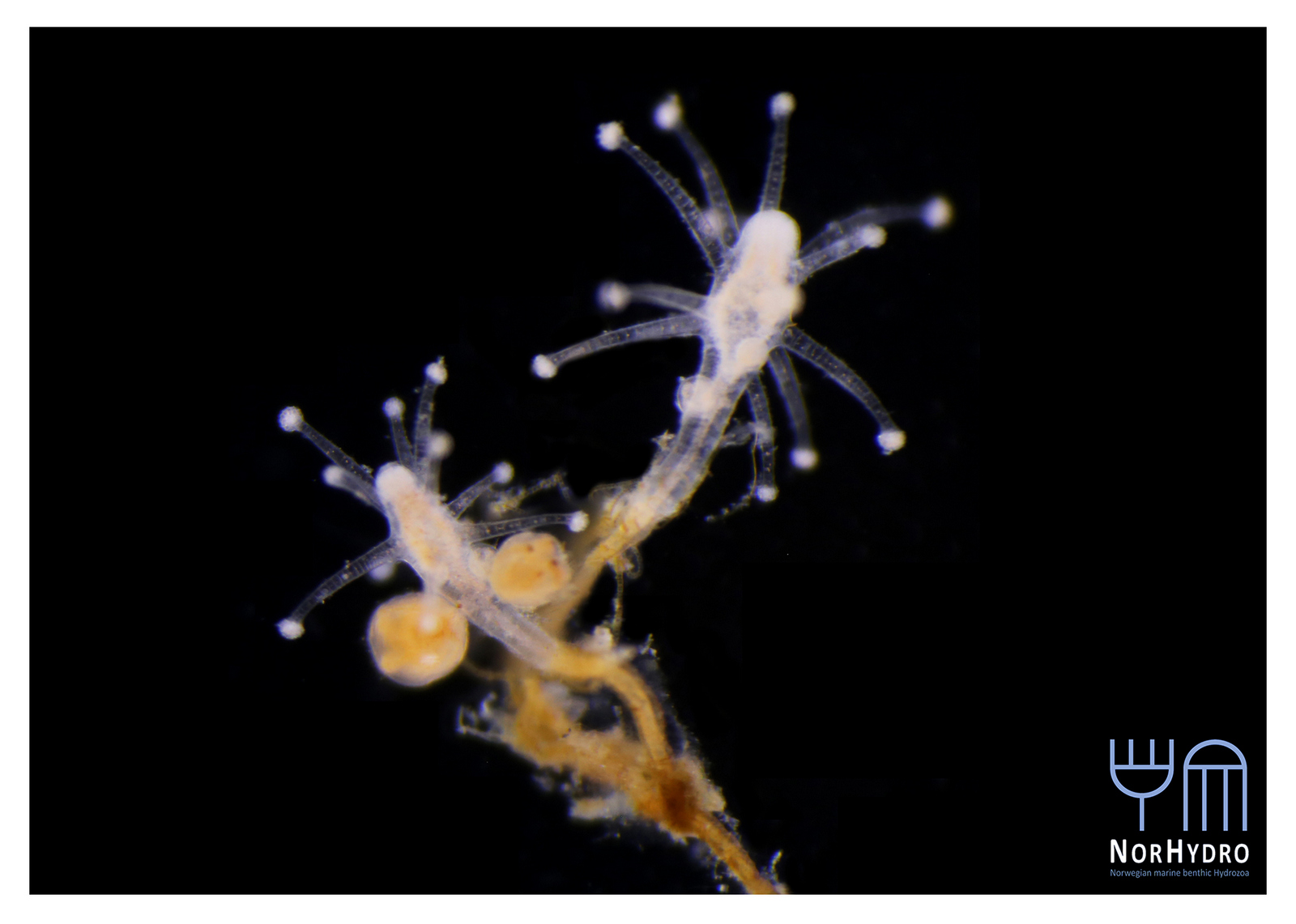

- Small corynid hydroids were often growing on other invertebrates and algae

- Polyps of Clava multicornis

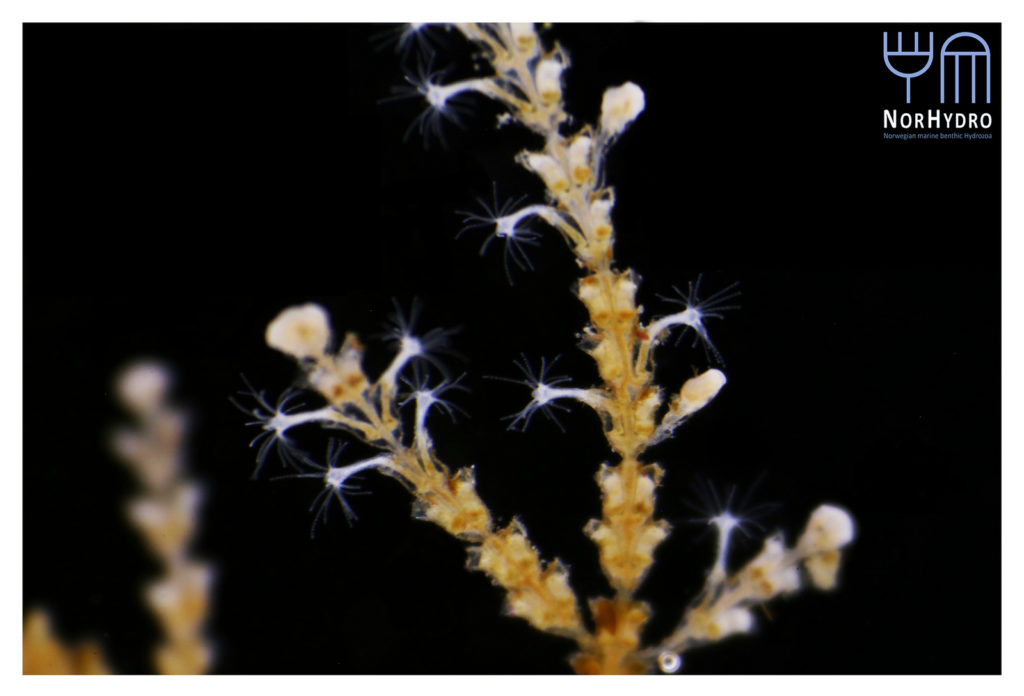

- Large colonies of hydroids (like this Eudendrium) were common in the area.

For those of you that know Norwegian, you can read another interesting account of our trip here, and there is even a small service covering our adventures filmed by the regional TV channel NRK Nordland here.

For those of you that know Norwegian, you can read another interesting account of our trip here, and there is even a small service covering our adventures filmed by the regional TV channel NRK Nordland here.

The TV service is worth a look to see the beautiful underwater images of the Norwegian coast even if you’re not familiar with the language!

– Luis