The “tree house”, headquarters of the Conservation and Research project of Vamizi Island

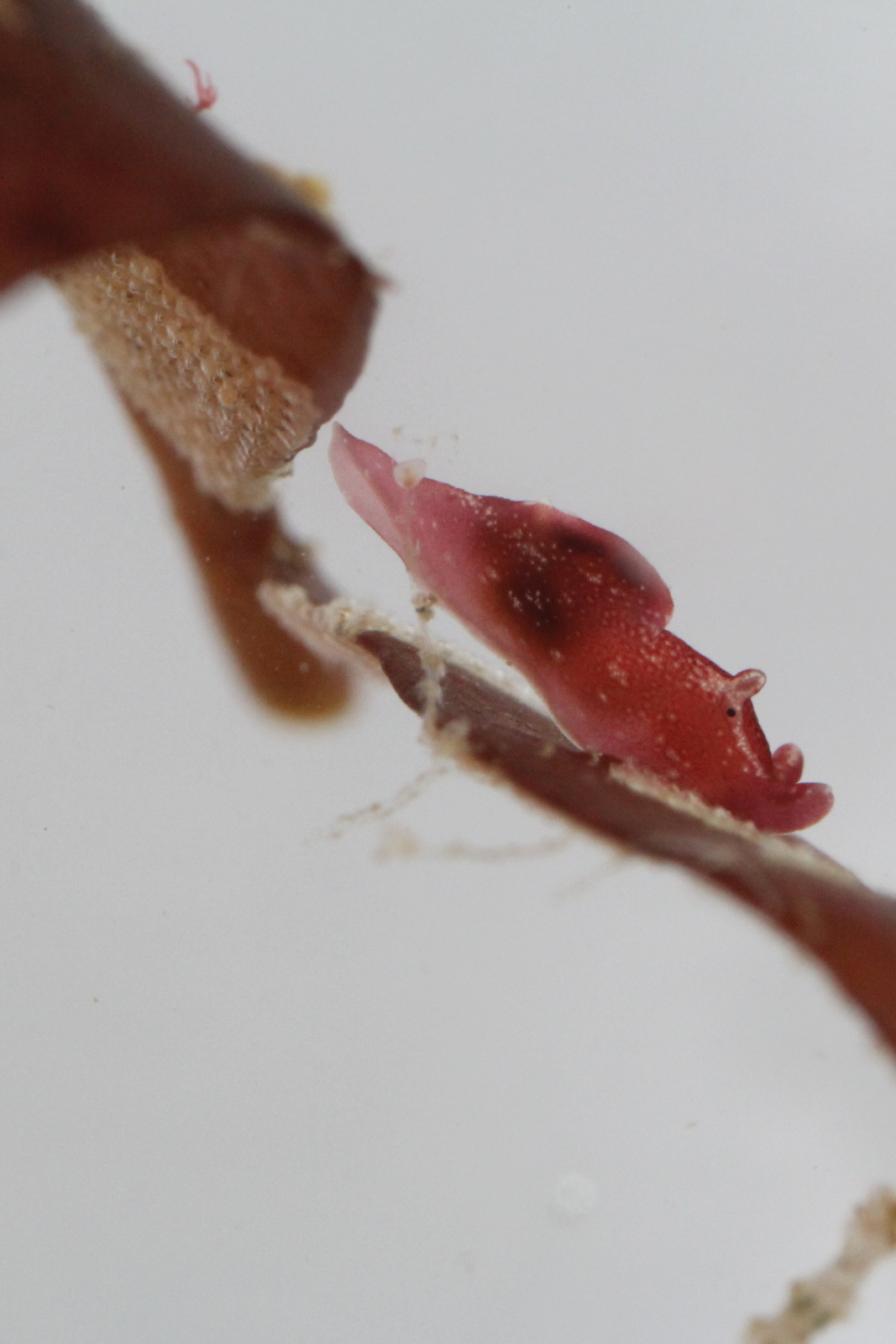

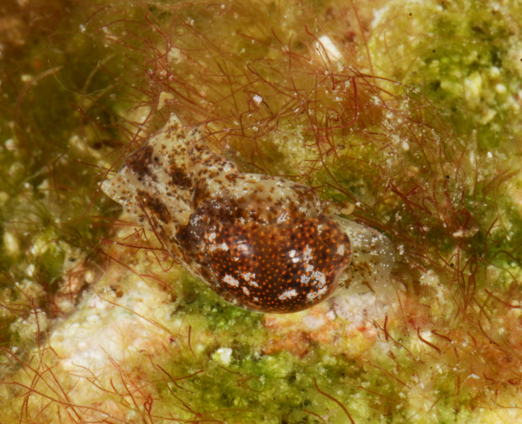

An undescribed species of an aeolid. Vamizi Island.

The tropical waters of the Indian Ocean are part of the world’s richest biogeographical region – the Indo-West Pacific (IWP), where diversity picks its high in the “Coral Triangle” an area confined by the Philippines, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea.

Within this vast realm, the east coast of Africa is probably the least studied area and Moçambique with one of the largest coastlines in the region and pristine mangrove, seagrass, and coral habitats hides a high and still largely unknown diversity of opisthobranch gastropods (sea slugs).

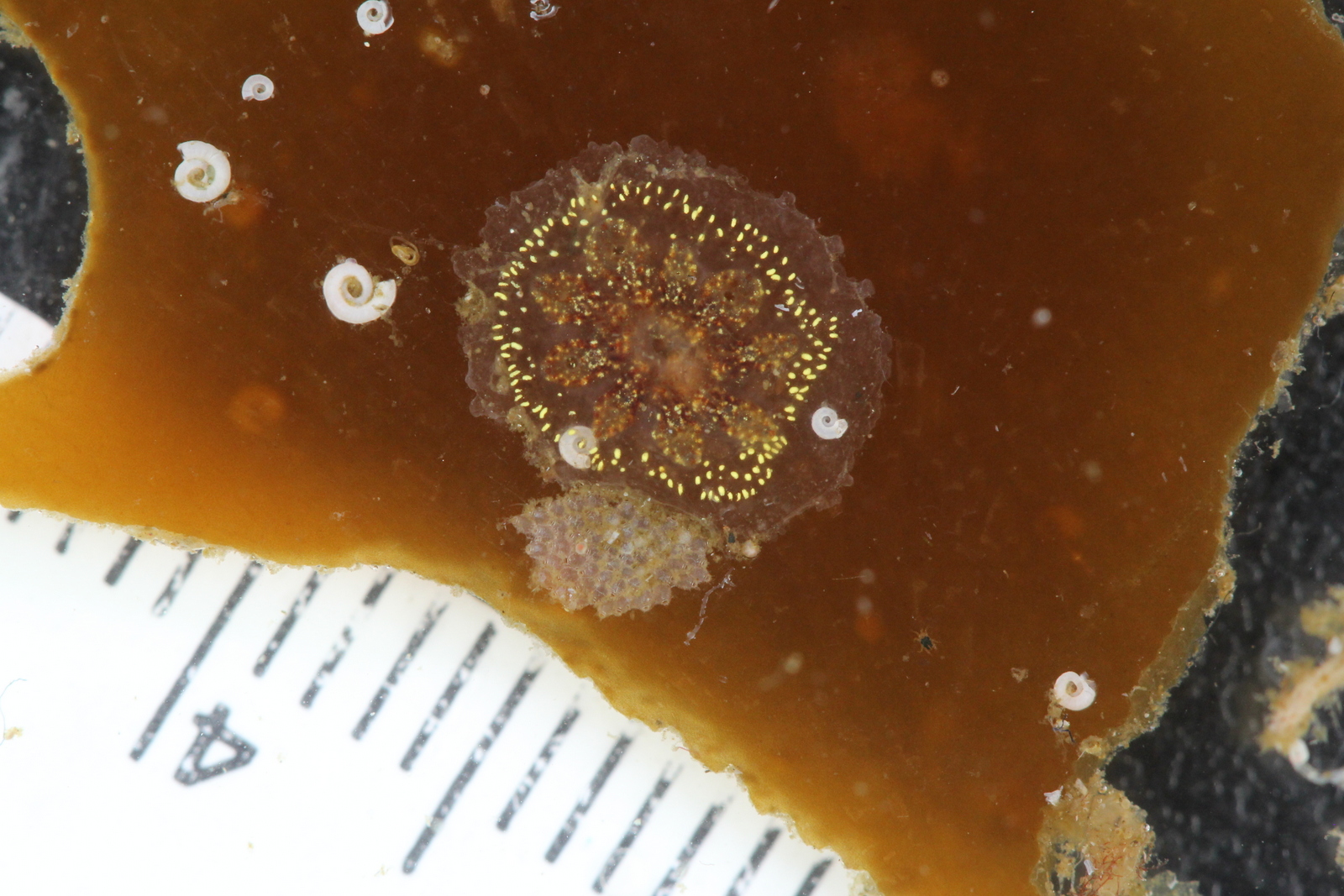

Phyllidia ocellata. Vamizi Island

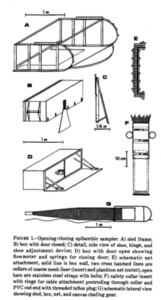

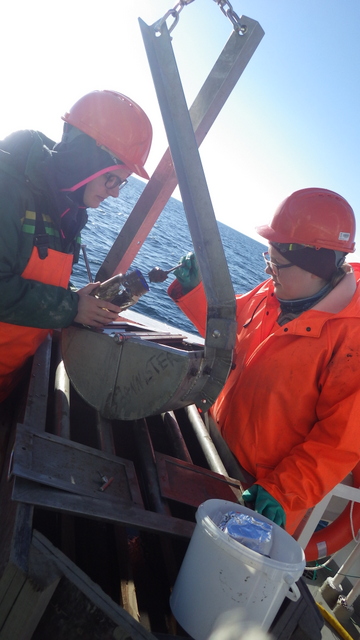

During January–February of 2014 I had the opportunity to sample in southern Moçambique together with local colleagues from the Zavora Marine Lab. The results have been so promising that we decided to organize a new fieldtrip but, this time to explore the fauna in the northern tropical latitudes of the country. In collaboration with the University Lúrio in Pemba and the Vamizi Conservation and Research Station managed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), we setup during May 2015 a two weeks fieldtrip to Vamizi Island, a remote pristine sanctuary located in the northern range of the Quirimbas archipelago. The goals were to continue the inventory of the sea slug fauna of Mozambique and Indian Ocean but also to collect specific material for several ongoing projects at the University Museum of Bergen (Natural History) related to the systematics, biogeography, and speciation of these molluscs.

Cerberilla ambonensis. Vamizi island

The first challenge was to reach Vamizi! Four flights, a five hours 4-wheels drive, and at last a boat trip – all of it during four days! But, the sight over the turquoise, calm, and warm waters of Vamizi was breathtaking and well worth the effort! We were very well welcomed by the team of the Conservation and Research Project of Vamizi and the management of Vamizi Island, which have provided all the necessary conditions for a successful and pleasant work.

The white sandy beaches and turquoise waters of Vamizi Island

The pristine coastline of Palma in northern Mozambique.

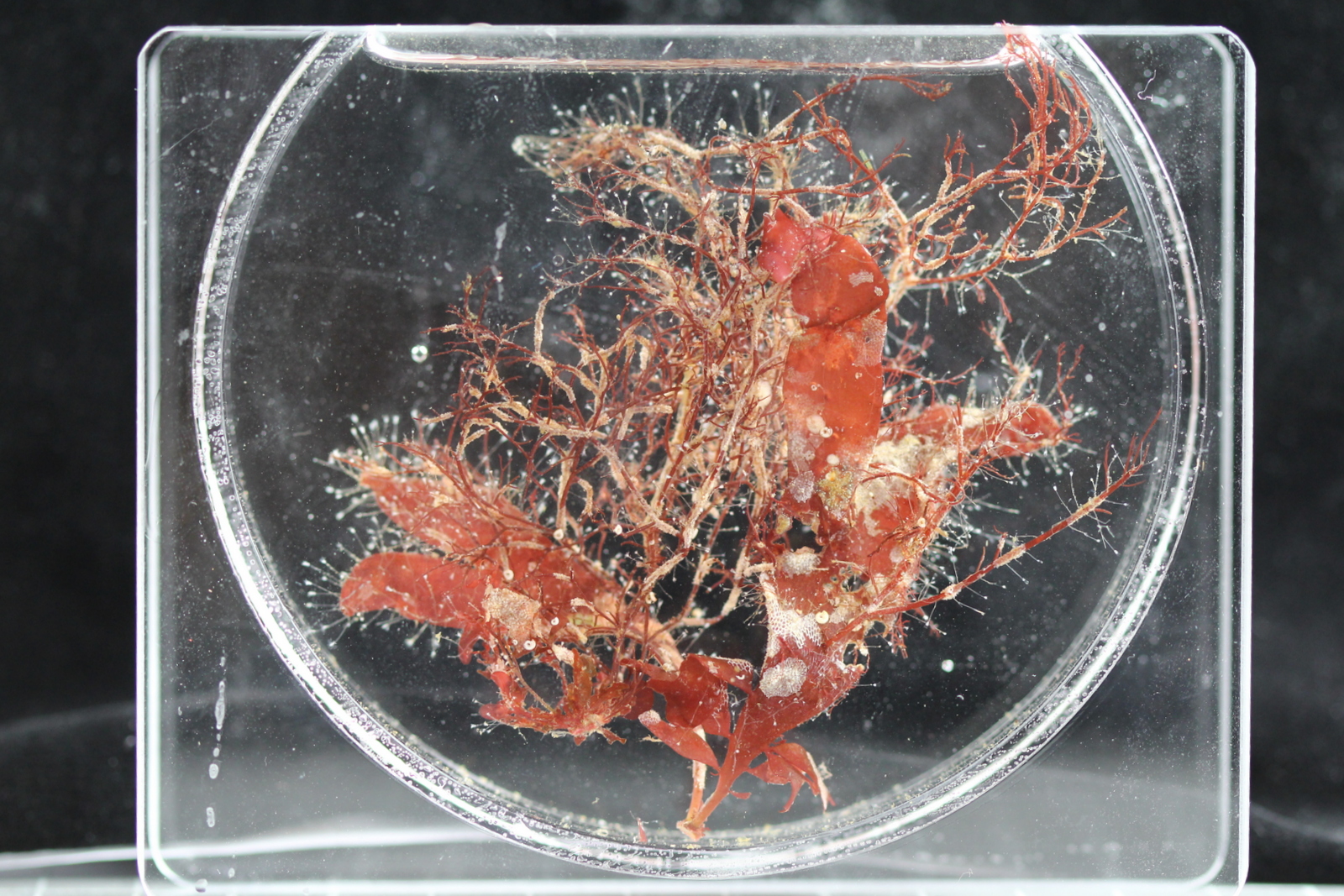

As the following days would unravel the pristine coral reefs, seagrass meadows and mangroves would not disappoint with their incredible diversity of sea slugs and all kinds of colourful marine live. Yet, and contrary to the experience of the previous year where we have collected in several southern sub-tropical areas of Moçambique (Vilankulo, Barra, Paindane, Zavora), this time was not so easy to find sea slugs and often each of us would not collect more than 4 to 10 specimens per dive; but steadily over the 2-weeks of fieldwork we reached the exciting number of about 85 species, with approximately 60 new records for Mozambique and around 14 new to Science. This seems to be a pattern on many pristine tropical areas; low abundances but high diversity of sea slugs.

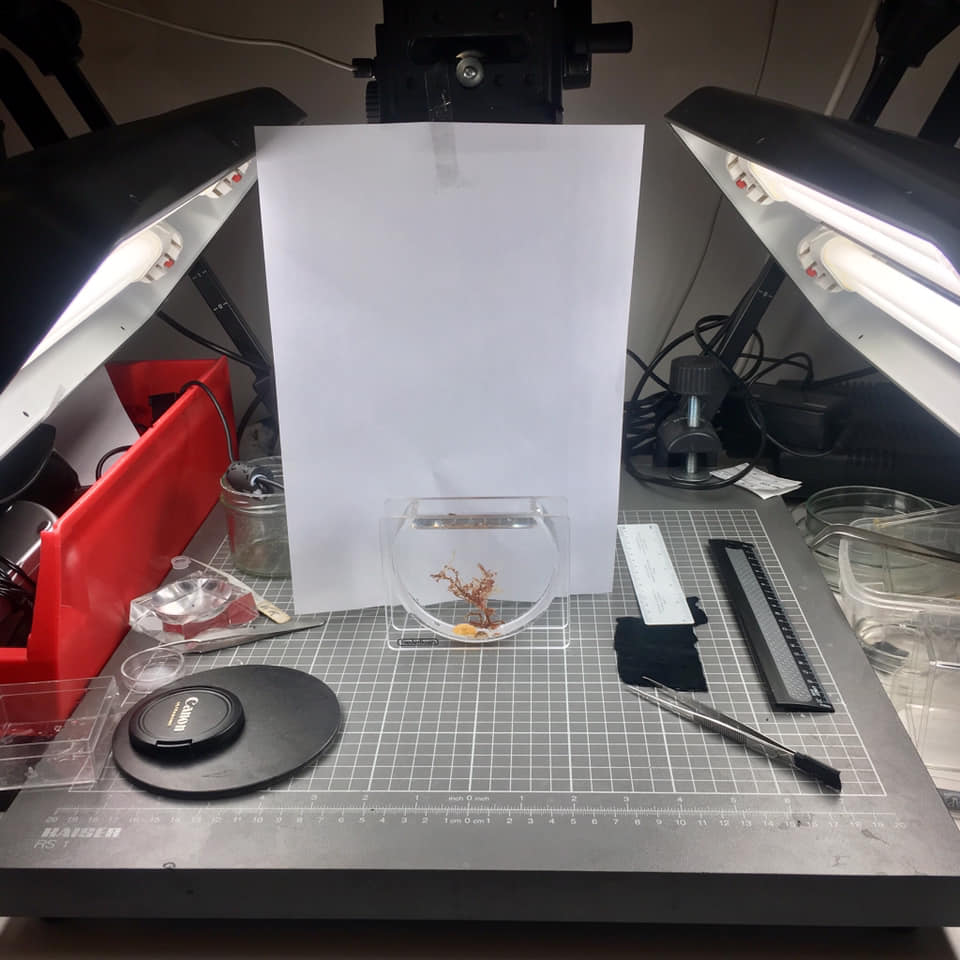

Photographing the daily catch

The “crew”. Left to right: Erwan Sola (University of KwaZulu-Natal), Isabel Silva (University Lúrio, Pemba / Vamizi Conservation and Research Project), Yara Tibiriçá (Zavora Marine Lab), Manuel Malaquias (University Museum of Bergen), and Joana Trindade (Vamizi Conservation and Research Project)

Transferring specimens to ethanol at Palma beach (Palma village not far from the border with Tanzania), under the puzzled eyes of a group of locals.

University Lurio. Newly graduated students with supervisors and opponents.

The farewell to Vamizi was not easy; the beauty, warm, and peaceful atmosphere of Vamizi together with its incredible underwater diversity and colours will last surely forever in our memories. Yet, the journey was not over! We headed to the town of Pemba for the last three nights where some formalities were still on the agenda.

Professor Isabel Silva from the University Lúrio in Pemba and member of the Vamizi Island Conservation and Research Project and a join-organizer of our expedition, have invited each member of the team to give a seminar at the university and to act as opponents on the defence of several theses of “licenciatura”. While my colleagues have talked about the sea slugs of Moçambique and the coral reefs of Vamizi Island, I decided to get a away from my field of research (but not of interest!) and discourse about “wired animals” such as loriciferans, xenoturbellids, kinorhynchs, and others… Biological diversity is definitely much more than turtles, sharks, whales, and manta-rays…, even goes beyond colourful sea slugs!

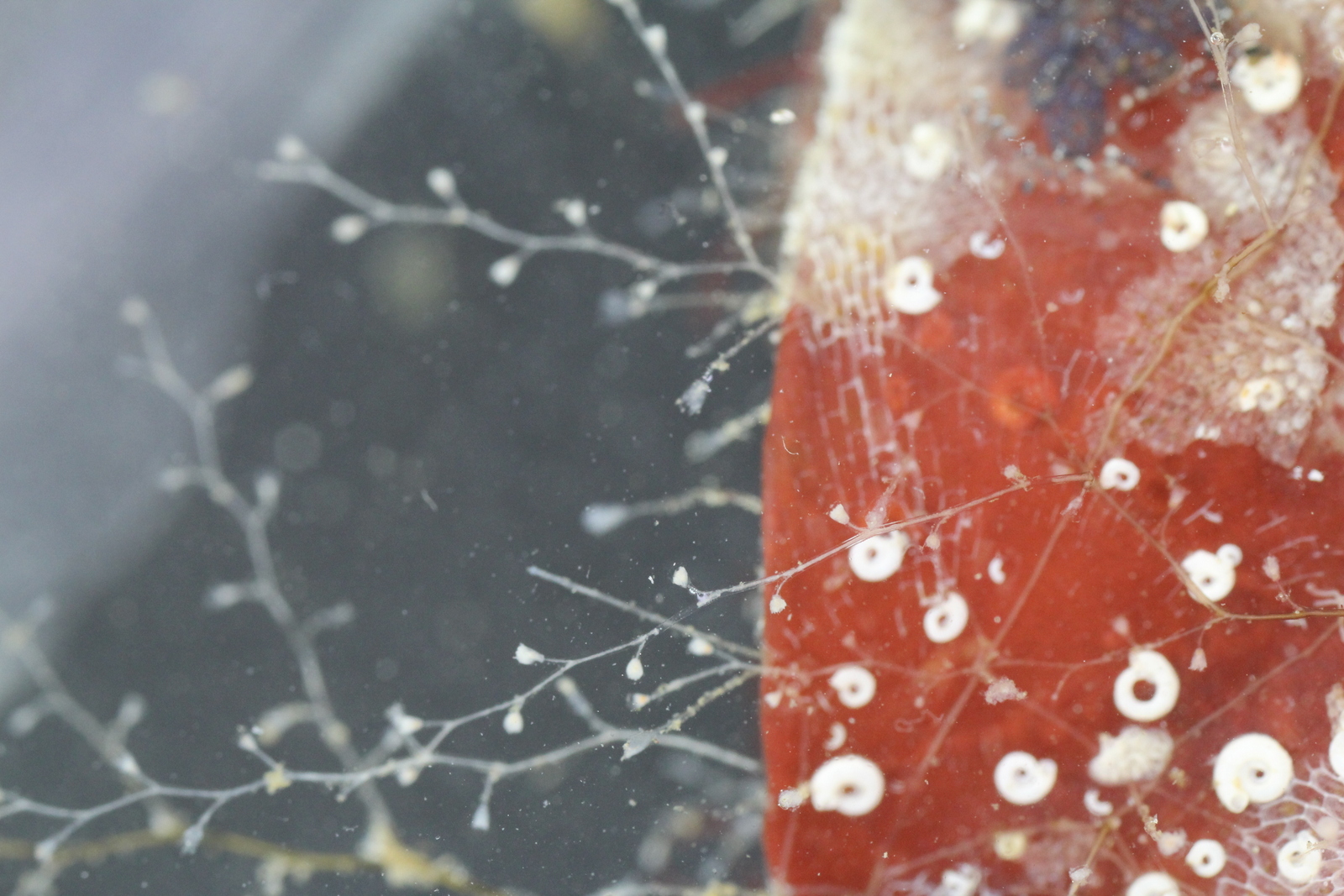

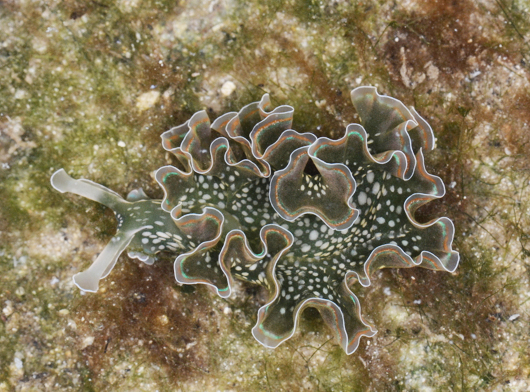

Melibe sp. Vamizi Island.

Is this a slug? Yes it is! Marionia arborescens. Vamizi Island.

Chromodoris cf. quadricolor. Vamizi Island.

Chromodoris boucheti. Vamizi Island

Chelidonura punctata. Vamizi Island.

Chelidonura mandroroa. Vamizi Island.

Chelidonura electra. Vamizi Island.

Phyllodesmium cf. magnum. Vamizi Island.

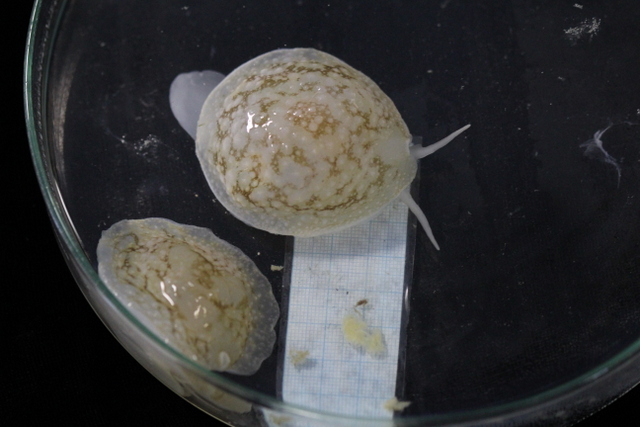

Cadlinella ornatissima. Vamizi island.

Baby green turtles recovered from a damaged nest, with a rare case of albinism in this group of reptiles.

Conservation “on the move”; Release of green baby turtles on the beach at Vamizi Island.

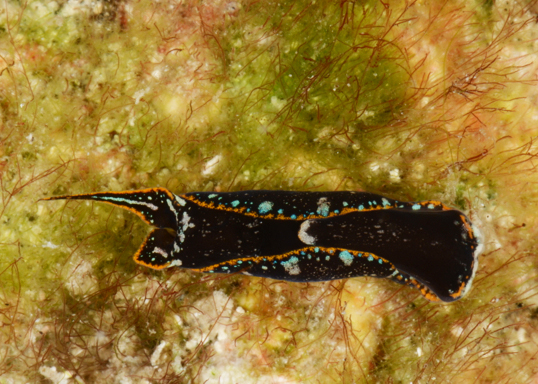

Philinopsis pilsbryi. Vamizi Island.

Coconut crab. Extinct to nearly extinct in many islands of the Indo-Pacific. Vamizi Island.

A “slimy” resident of Vamizi Island locally named “jibóia”.

A kingfisher bird. Vamizi Island.

An uninvited guest in my bedroom.

A weaver bird. Vamizi Island.

-Manuel