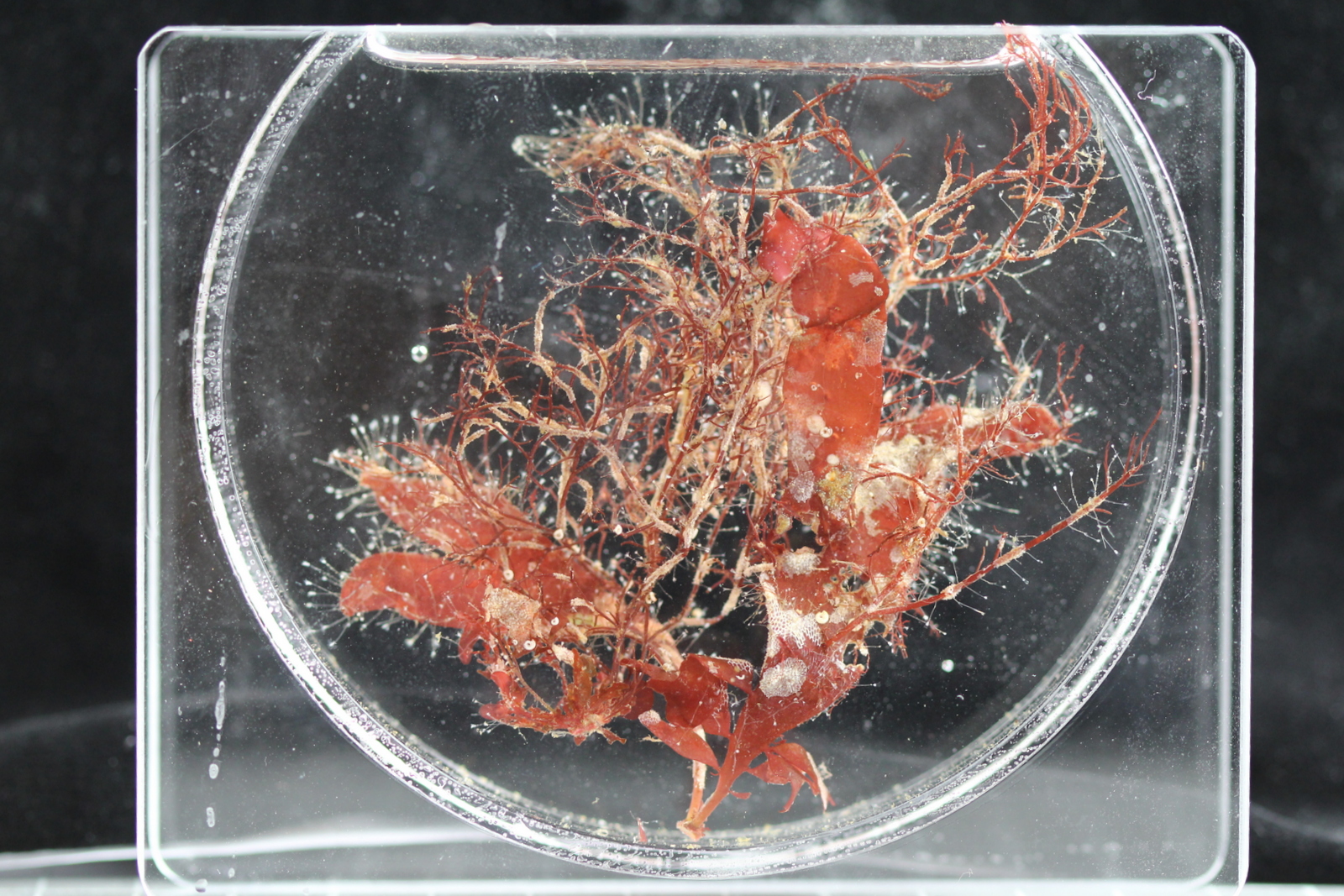

“Sea slugs” include both the by far most famous nudibranchs, and groups such as the Sacoglossa (sap-sucking slugs, more about these later in the calendar!) and Cephalaspidea (the bubble snails), amongst others. These latter ones often do have shells – but reduced ones, too small for the animals to completely retreat into, like this Haminoea:

Nudibranchs, however, are the “naked” snails: Their name “nudibranch” comes from the Latin nudus, naked, and the Greek βρανχια, brankhia, gills. They don’t have a shell, but this wasn’t always the case. In their early larval life stage, they actually have a shell, but when settling down and transforming from zooplankton into adults, they lose the shell. The loss of the shell in adults might be responsible for the amazing diversity we see in body forms present in sea slugs.

So, in this basic anatomy of sea slugs we will focus mostly on the body forms of nudibranchs, but all other sea slug orders are not far off from this anatomy, if you know the basics of nudibranchs, you can extrapolate to the other orders as well. So here we go!

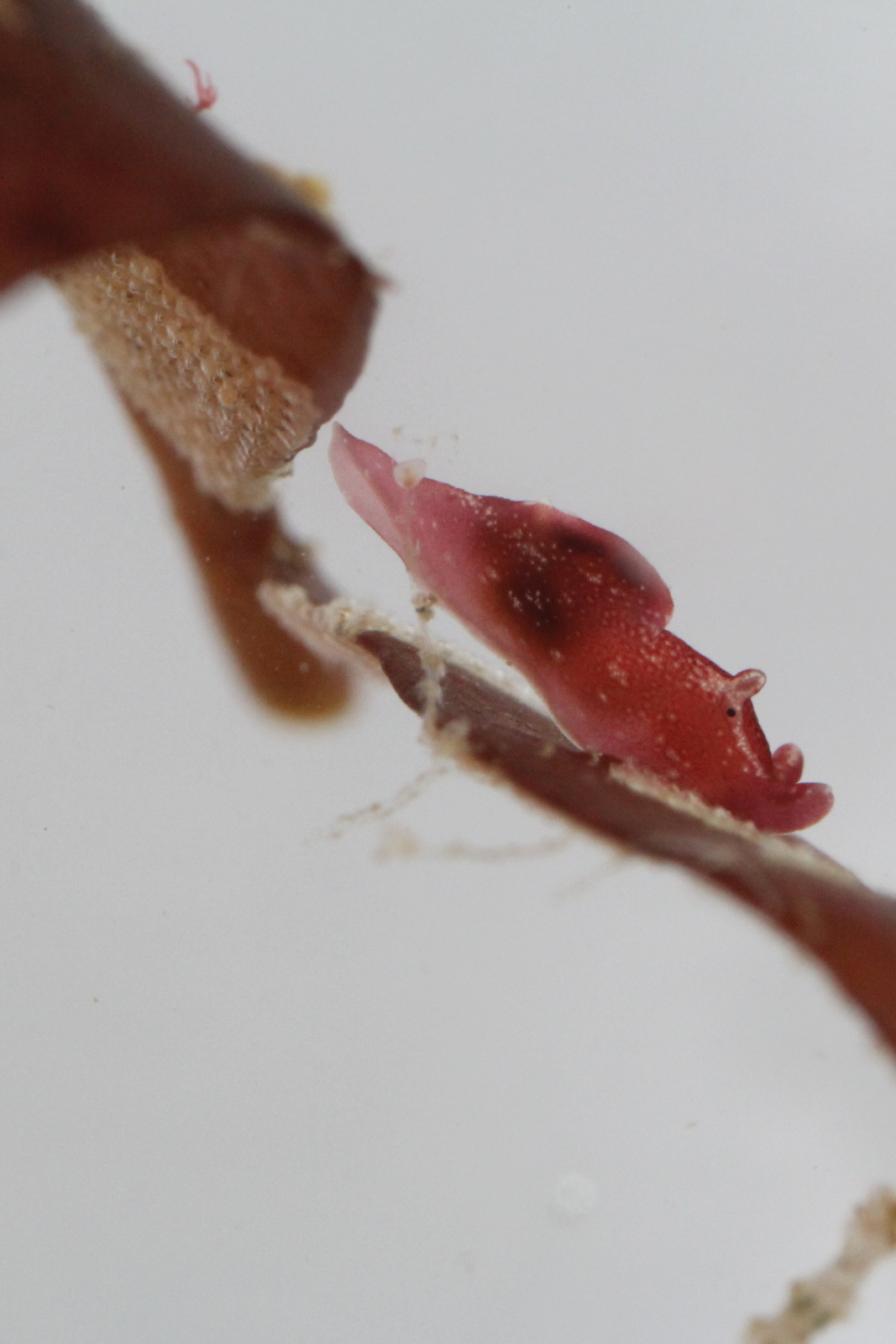

Nudibranchs are roughly divided in two type of body forms; the dorid nudibranchs and the aeolid nudibranchs.

Two basic body types found within the Nudibranchia; the dorids and the aeolids. (Illustration: C. Rauch)

The dorid nudibranchs have a thick mantle that extends over their foot. In some species the surface of the mantle is covered with tubercles than can vary in different sizes, numbers and shapes. This gives them often a rigid body that offers some protection. In most of the dorids it is the mantle that contains toxins to defend themselves, the toxins are extracted from their food sources.

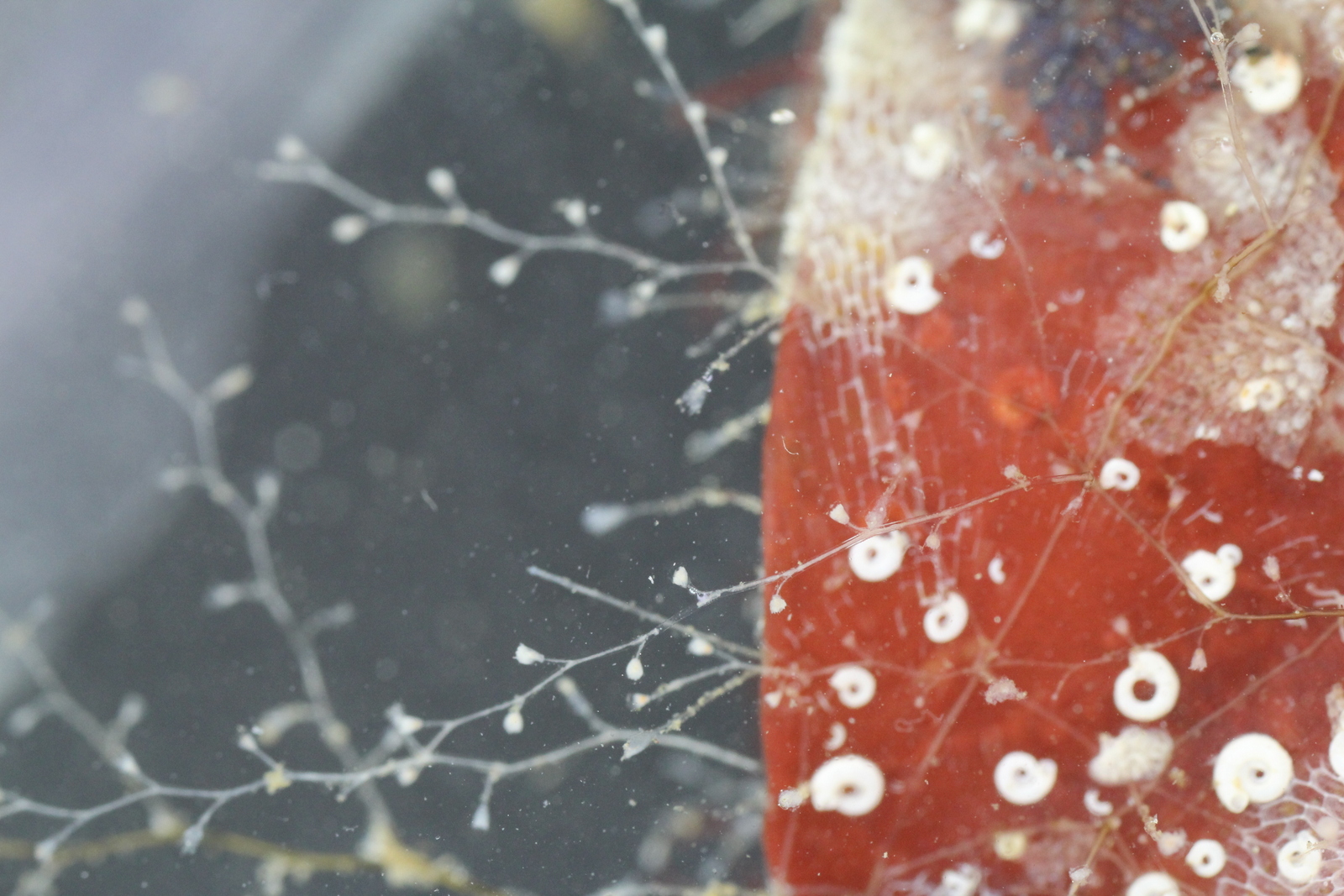

Aeolid nudibranchs have mantles that are covered with finger-like extensions called cerata. The cerata are very special as they contain branches of the digestive tract, and in some species, this is also visible! The tips of the cerata contain special organs called the cnidosacs. Cnidosacs store stinging cells (called nematocysts). These are obtained from their food source which are often cnidarians like hydroids, sea-anemones and soft corals. The cnidosacs are activated when the nudibranchs feel threatened and the stinging cells will be discharged!

All sea slugs have rhinophores. On the head of all sea slugs you can find a pair of sensory tentacles called the rhinophores. They detect smell and taste and in most of the dorid nudibranchs the rhinophores can be retracted into a basal sheath. Sea slugs know all kind of shapes of rhinophores which are a very important tool for identification of the species.

Besides a pair of rhinophores many nudibranchs also have a pair of oral tentacles, one on each side of the mouth. They are most likely involved in identifying food by taste and touch.

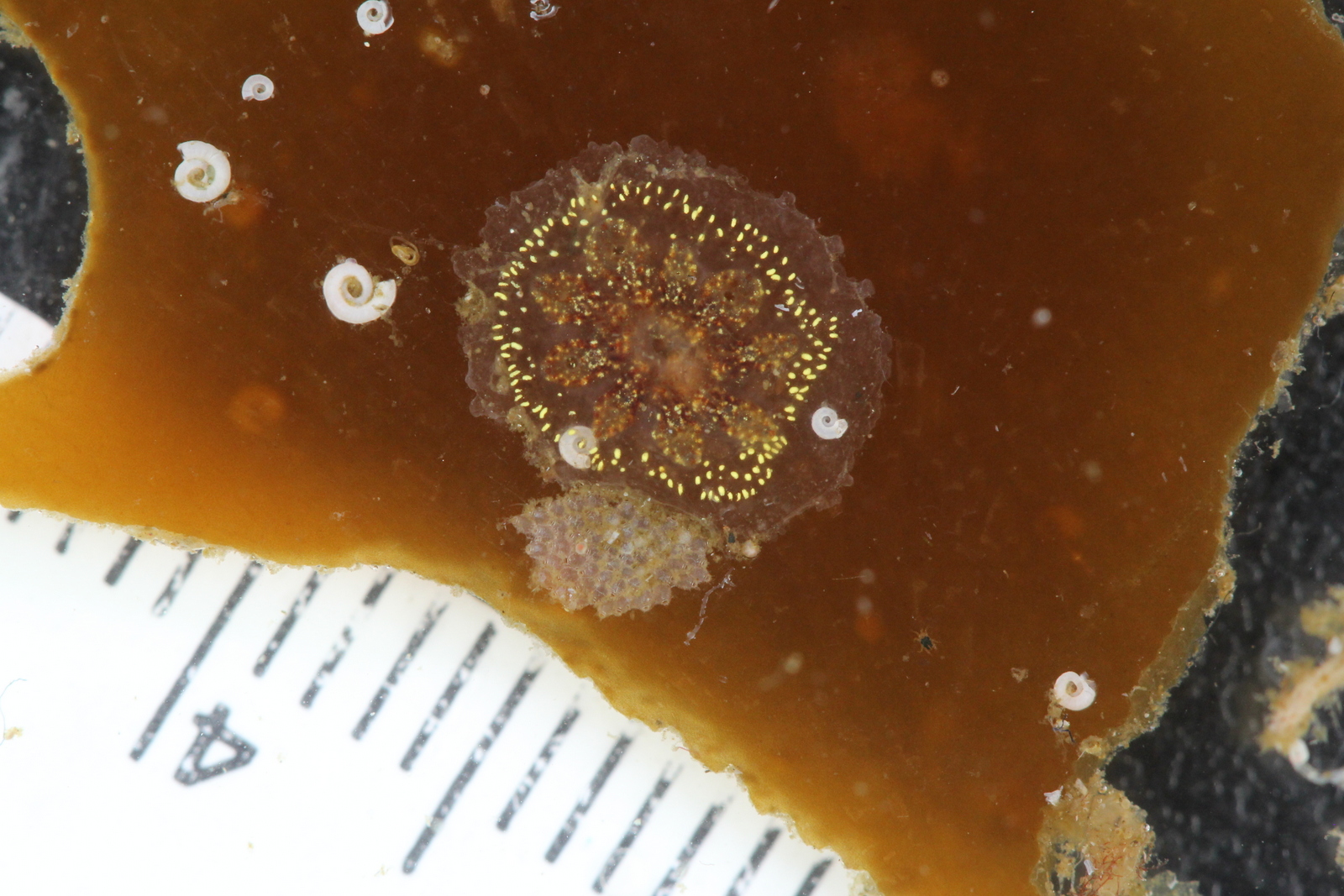

Sea slugs also need to breathe oxygen. They do this via the surface of their entire bodies, but their main reparatory organ are their gills. Dorid nudibranchs have often a feather like structure encircling their anus on the back of their body (the branchial plume). Some dorid species can also retract their gills into a pocket. Within the aeolid nudibranchs the cerata act like gills by diffusing oxygen from the surrounding water. The cerata are sometimes branched in order to increase the surface area, also here, like the rhinophores, different species can have different forms of cerata.

-Cessa