A guest post from two of our MSc students (in this case co-supervised with NTNU) who were here on a research visit for three weeks in January 2024.

We are Maria Buhaug Grankvist and Ellisiv Tomasgard Raftevold, and for the past three weeks we have been visiting the University Museum in Bergen to work on our master’s projects. It’s been a lot of fun, a lot of hard work and very useful, as the Bergen University Museum really is the place to be when you’re working with marine invertebrates.

Both our theses focus on marine invertebrates, but two different phyla. Maria is working with cyclostomatid Bryozoans, while Ellisiv looks at Polychaetes. We write our masters for the NTNU University Museum in Trondheim in collaboration with the University Museum in Bergen and the projects “Digitization of Norwegian Bryozoa” (NorDigBryo) and “Marine Annelid Diversity in Arctic Norway” (ManDAriN). Keep reading, and you will learn about our projects and what we recommend to do when visiting Bergen!

Ellisiv’s marine annelids:

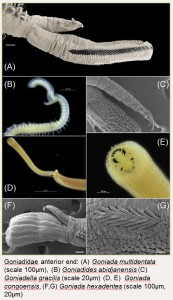

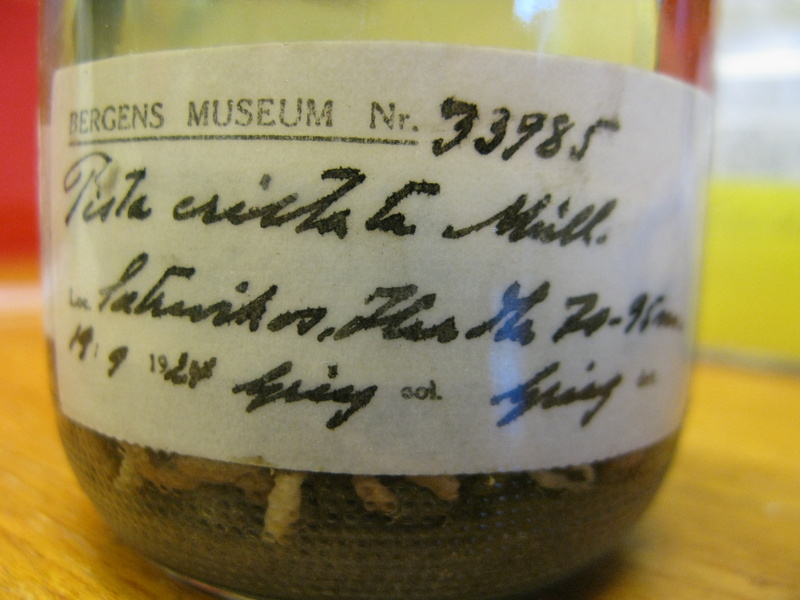

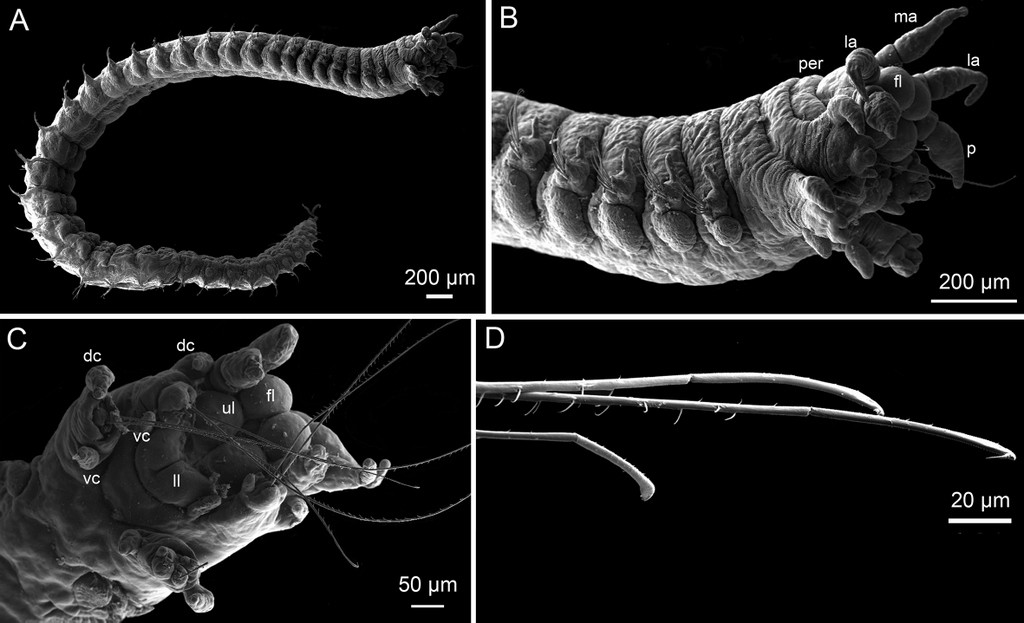

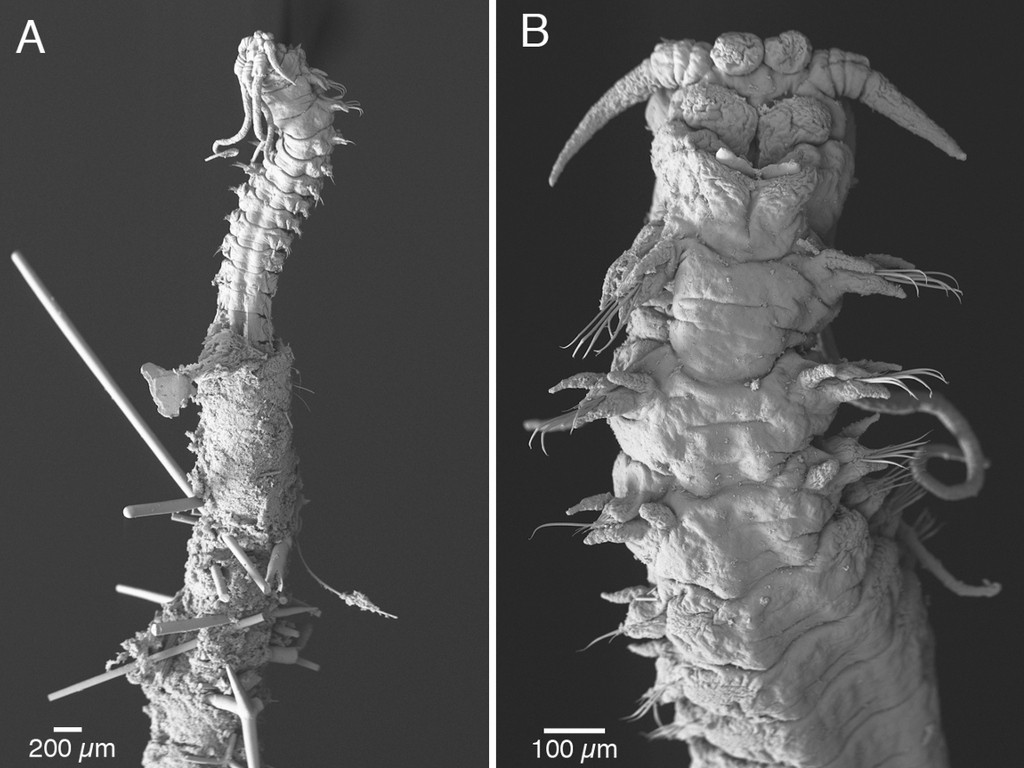

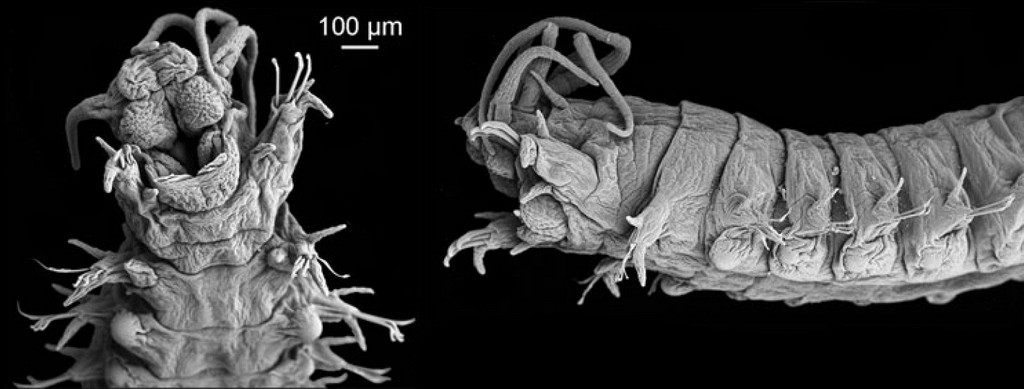

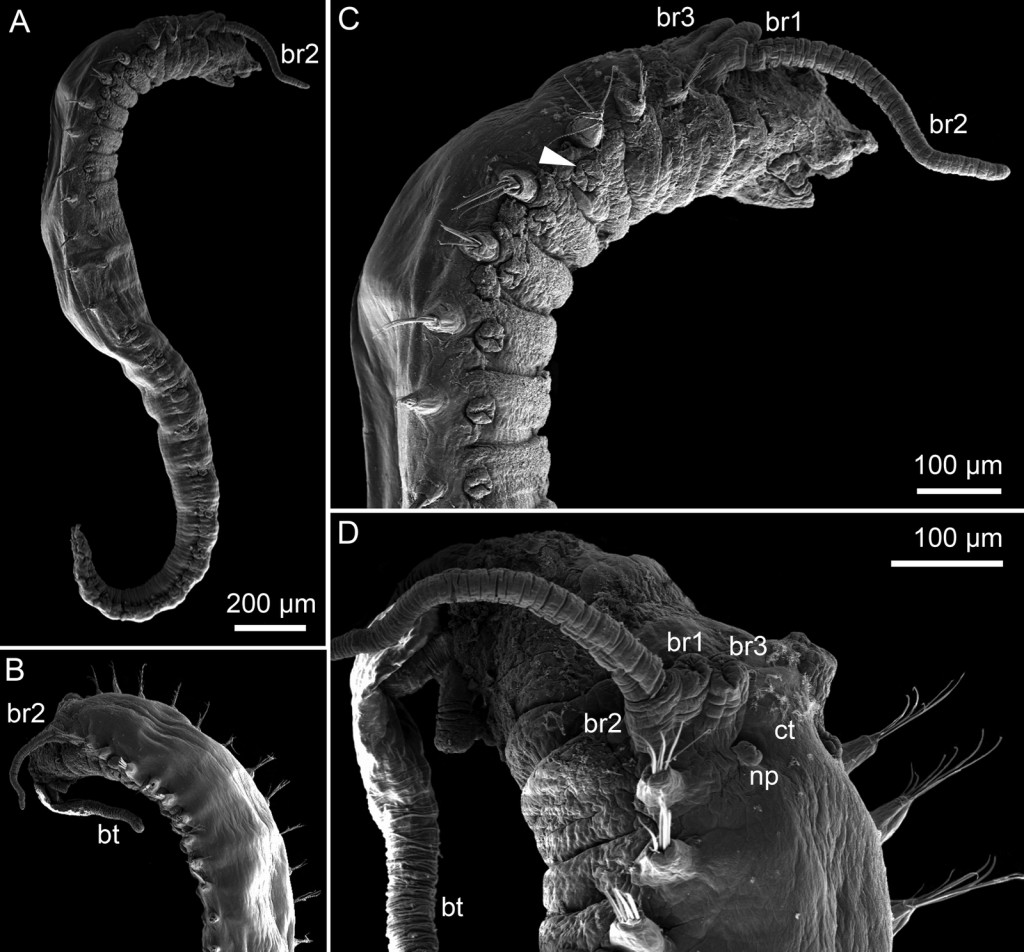

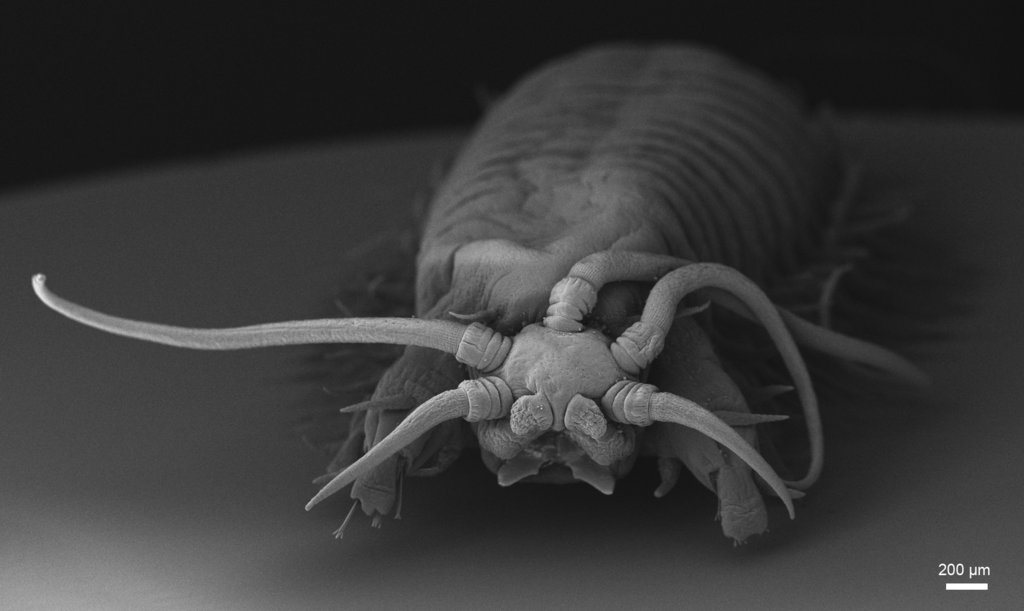

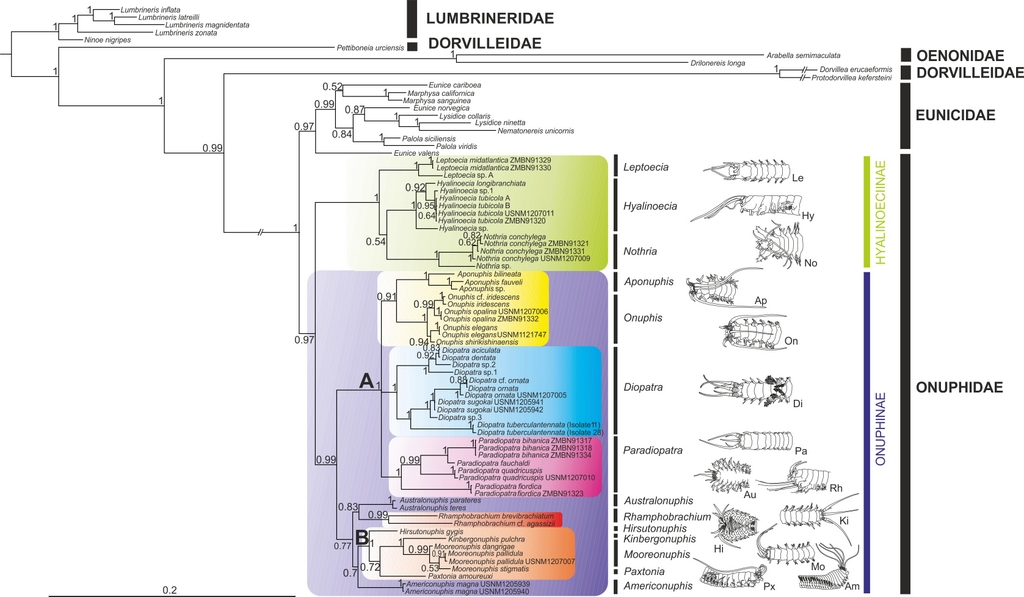

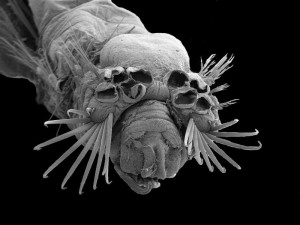

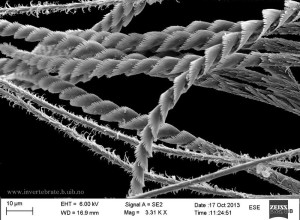

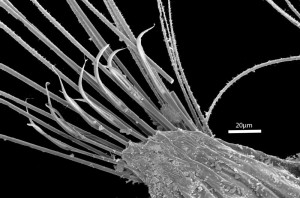

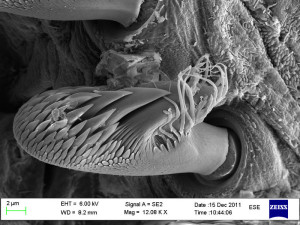

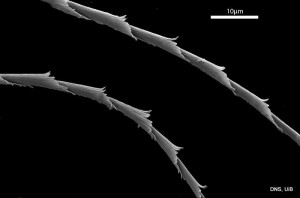

I’m Ellisiv and in my master’s thesis, I study a marine Annelid or Polychaete genus called Flabelligera within the family Flabelligeridae. Flabelligerids are mostly benthic and can be found from the intertidal zone down to the deep sea. They like living in the sand or mud, or under rocks, and they can be quite small and have sediment camouflage or a completely transparent body and outer sheath and may therefore be quite hard to find. If you do find them they are quite cool to look at, and if they are transparent, you can see their internal organs and green circulatory system. Their most prominent character is the cephalic cage, which is a circle of bristles around their mouths forming a kind of cage. In the ecosystem, these animals have an important role in that they for example eat the marine snow that falls to the bottom of the oceans so that it can be recycled back into the food chain.

- Figure 1 Specimens sorted to F. affinis, specimen on ethanol to the left (Picture: Ellisiv T. Raftevold).

- and a alive specimen to the right (Picture: Maria G. Buhaug)

Flabelligera affinis, a species within this genus was until recently thought to be only one species and was thought to have a worldwide distribution. This, however, was shown not to be true when Salazar-Vallejo 2012 restricted F. affinis to arctic areas and reinstated F. vaginifera which was previously synonymized with F. affinis, and proved that it was at least two different species sorted into one. Also looking at the material we have in the museum collections and DNA samples it was suspected that there are multiple different species sorted into F. affinis.

This is the problem I am trying to solve in my master’s thesis, and to do this I need to study the specimens found in the museum collections that are sorted to F. affinis and look at their different morphological characters and sort them into groups. This is mostly what I have done in Bergen. However, these species are very similar, and sequencing their DNA to look at their relatedness is a very useful addition to the morphology. Hopefully, I can get a step closer to solving this taxonomic confusion in my master’s and we can get to know how many species are hiding within Flabelligera.

Maria and the bryozoans:

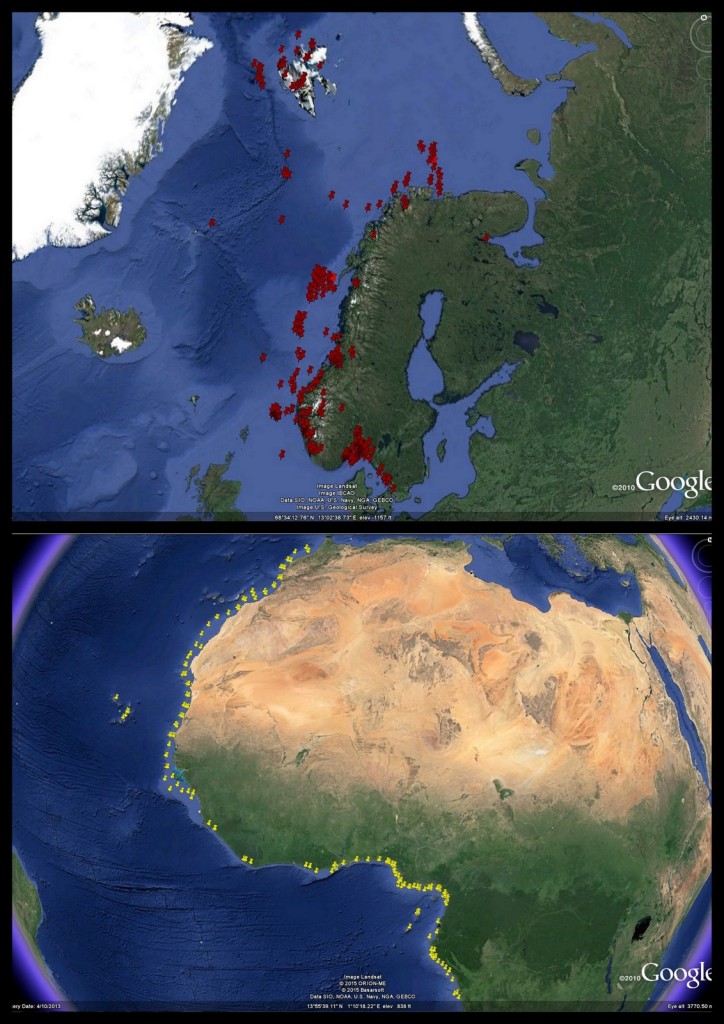

I’m Maria, and for my master thesis I’m recording the diversity of bryozoan species within the order Cyclostomatida in Norwegian waters (meaning off the coast of Norway, the arctic ocean and some nearby areas). In addition to creating a checklist of recorded species, I’m mapping out their geographic and bathymetric distribution. In short, I’m trying to provide an answer to the question: What species of Cyclostomatida do we have, and where do they live?

- Two bryozoan colonies representing different orders. Above is a un-calcified type of bryozoan colony belonging to the order Ctenostomatida.

- Coronopora truncata, a species of cyclostomatida with a heavily calcified skeleton. This is the very bryozoan colony that sparked my fascination for cyclostomatids when it came up from a benthic sample during a field course in Agdenes in the summer of 2022. Photos: Maria Buhaug Grankvist

There are two main reasons for studying this particular phylum in my thesis. First, they are strongly understudied, and according to a report published by the Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative in 2021, our understanding of bryozoan distribution and ecology is weak and unsatisfactory, even with “essential knowledge gaps” in some areas.

The second reason explains why it’s an issue that we know so little about these animals: They are majorly important for many marine ecosystems! Nearly all bryozoans are colonial, so even though the zooids (term for an individual animal in a colony) is only 0,1 – 0,5 mm long, the colonies can be as much as half a meter tall or wide! Many of the colonies have intricate shapes supported by heavily calcified structural zooids, providing habitats for a wide range of other animals. In this way, the bryozoans promote biodiversity in much the same way corals do, but they are far less known and barely protected by law like their coral counterparts.

To protect these beautiful colonial creatures we first of all need to know them better. Mapping the actual diversity and distribution of Norwegian bryozoans is far too large a task for a two year master thesis, but my thesis will hopefully contribute to the final results of the NorDigBryo project.

DNA sequencing

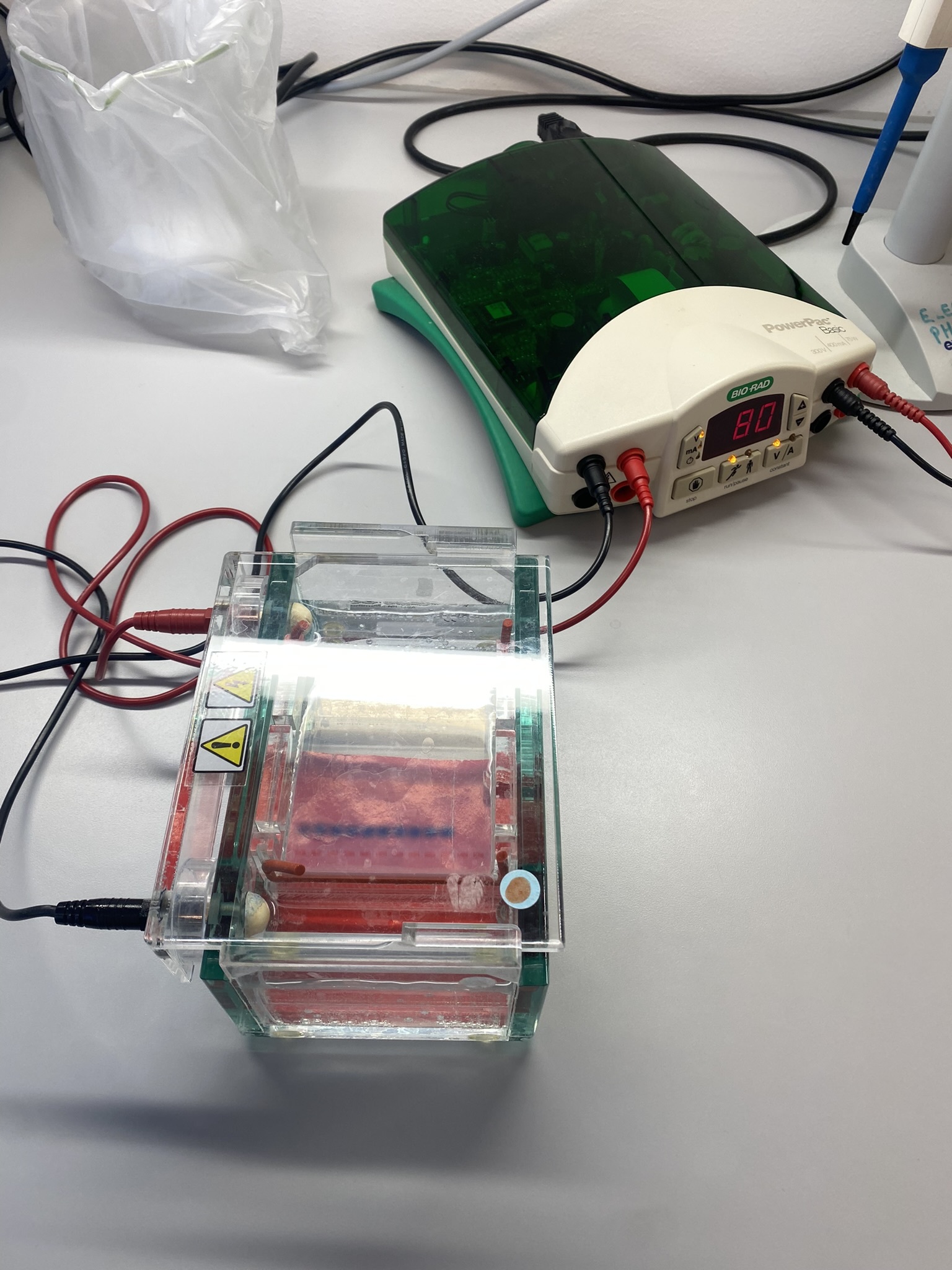

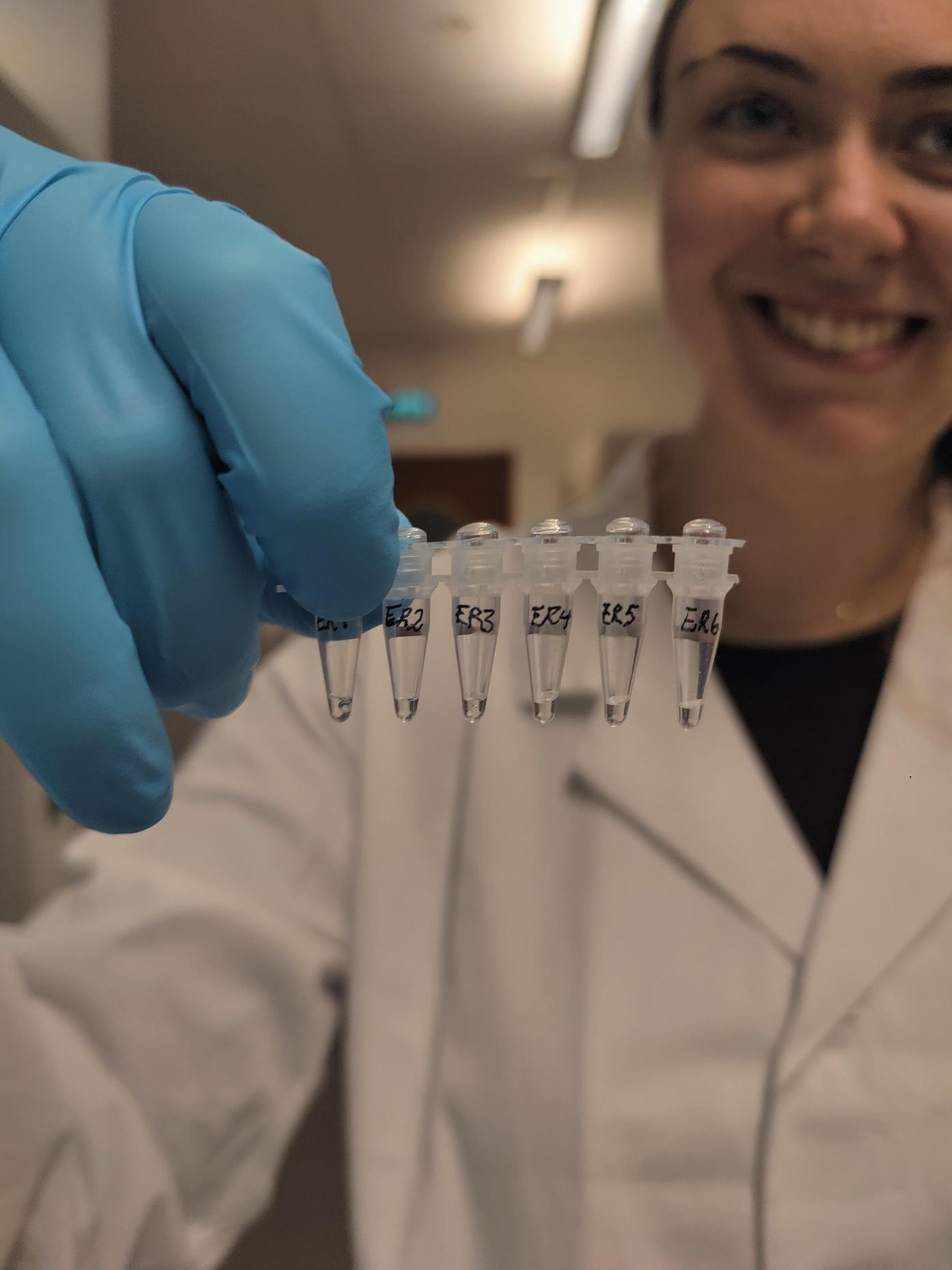

For both our theses we use an integrative approach, combining the morphology (what we see/the physical traits of the animals) with genetic sequence data. DNA sequencing is one of the things we got to do in Bergen, and it was very interesting to see how this is done from start to finish. We got to extract the DNA, use PCR and specific primers to amplify the DNA string of interest and gel electrophoresis to test if the prior methods worked.

- Figure 2 Readying the samples and running the gel electrophoresis (Pictures: Ellisiv T. Raftevold)

For the successful sequences, we got to try the Sanger sequencing method, and it is very exciting to get to use some of our own sequences in our theses.

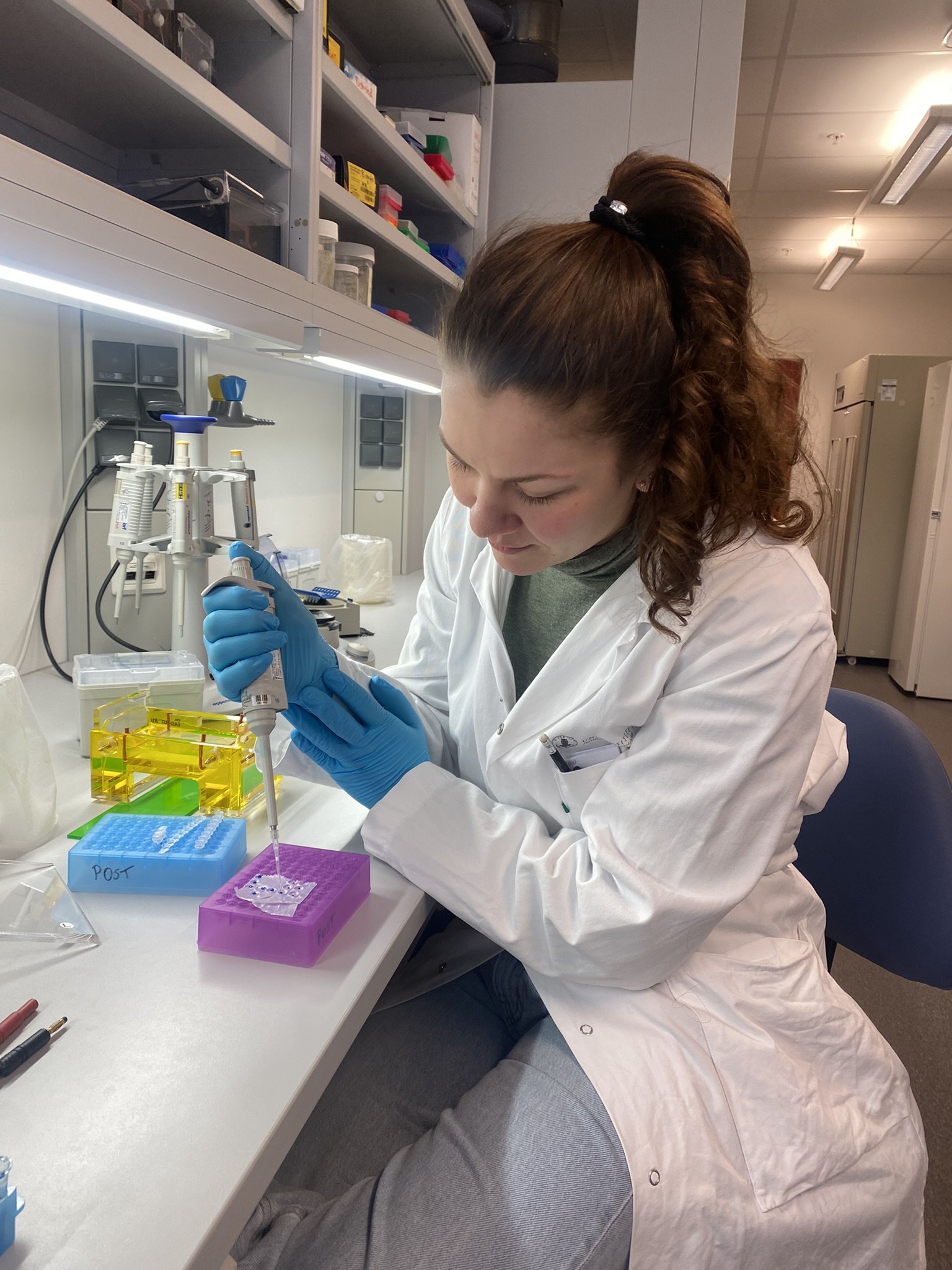

- Figure 3 Pipetting the DNA extracts and readying them for Sanger sequencing,

- and the finished samples ready for analysis (Pictures: Maria B. Grankvist)

When in Bergen:

You’d might think that when we finish long days at the university museum, looking at marine invertebrates from dusk till dawn, we would go and do something completely different when the weekend comes. You’d be wrong!

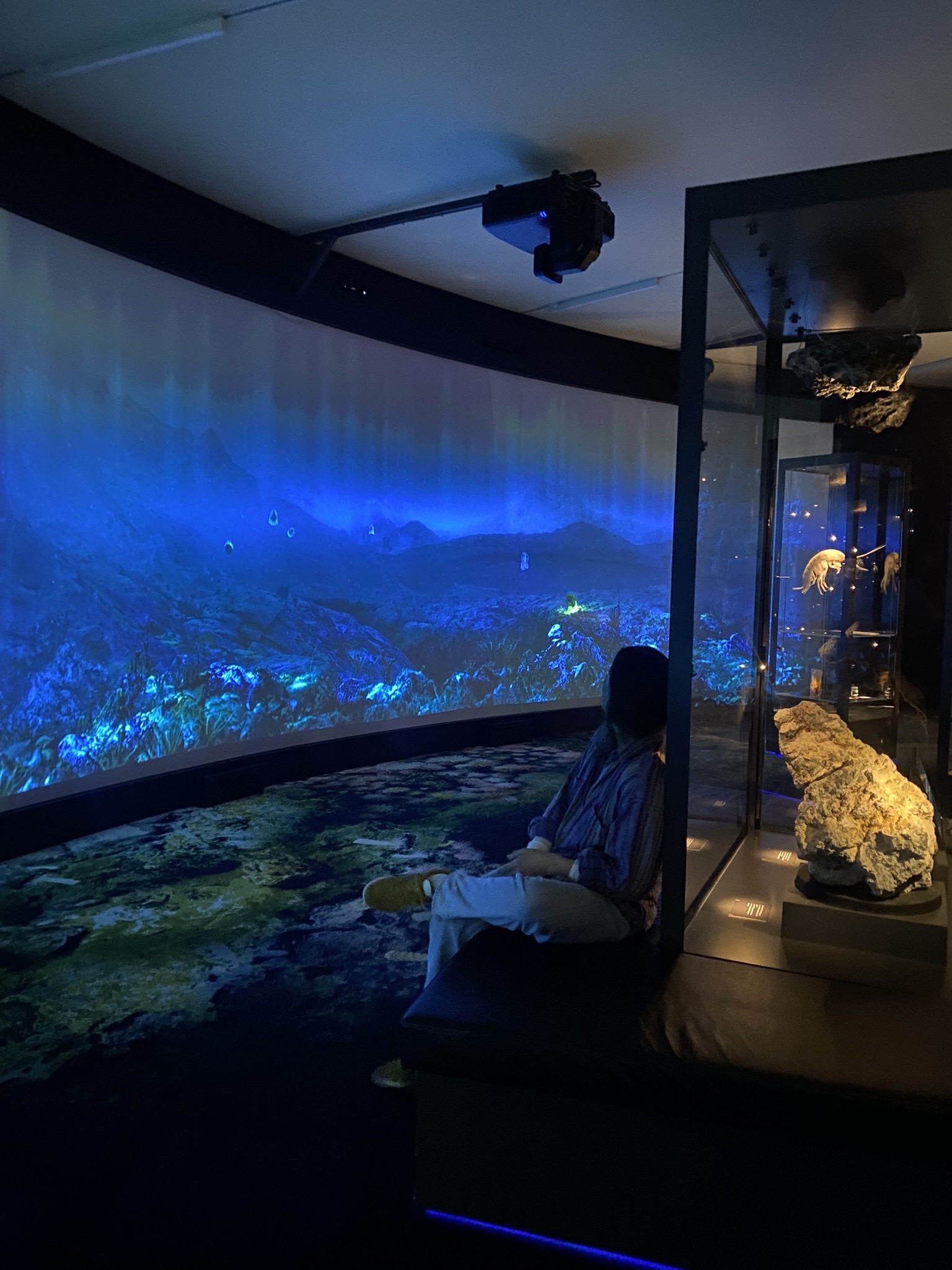

In our spare time in Bergen, we went to see the University Museum of Natural History and were there almost from when it opened until it closed because there were so many interesting exhibitions. There are so many beautiful creatures on the planet, many of them and the story of how they evolved, you can learn about at the museum. We of course especially loved the “deep sea-room” where we would sit for a long time while watching a cephalopod swimming around deep sea sulfur vents..soothing.

- Figure 4 Visiting the natural history exhibitions. The whale hall and

- the deep sea exhibitions were especially interesting to us (Pictures: Ellisiv T. Raftevold)

More about the projects:

Marine Annelid Diversity in Arctic Norway (ManDAriN) home page (UiB)

ManDAriN presented at Artsdatabanken

Digitization of Norwegian Bryozoa (NorDigBryo) home page (UiO)

NorDigBryo presented at Artsdatabanken

NorDigBryo is also on Instagram – give us a follow!

-Ellisiv & Maria

It was our pleasure hosting these two enthusiastic guests, and we wish them luck in the thesis work – stay tuned for updates!

PS: Interested in a marine master thesis at the University Museum of Bergen? Check out the blog detailing potential projects, or get in touch with the staff listed!