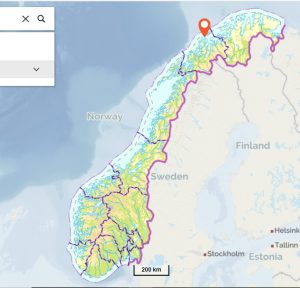

As part of the Lower Heterobranchia and Pyramidellidae project funded by Artsdatabanken, an international taxonomic workshop was held at the Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen, from 8–12 September 2025. The workshop brought together Dr Bastian Brenzinger from the Bavarian State Collections in Munich, Germany, and Dr Kennet Lundin from the Gothenburg Natural History Museum, Sweden. The event was organized by Prof. Manuel Malaquias (project leader) and Dr. Cessa Rauch (project technician) and included the participation of Jon Kongsrud, collection manager of the invertebrate collections at the University Museum of Bergen.

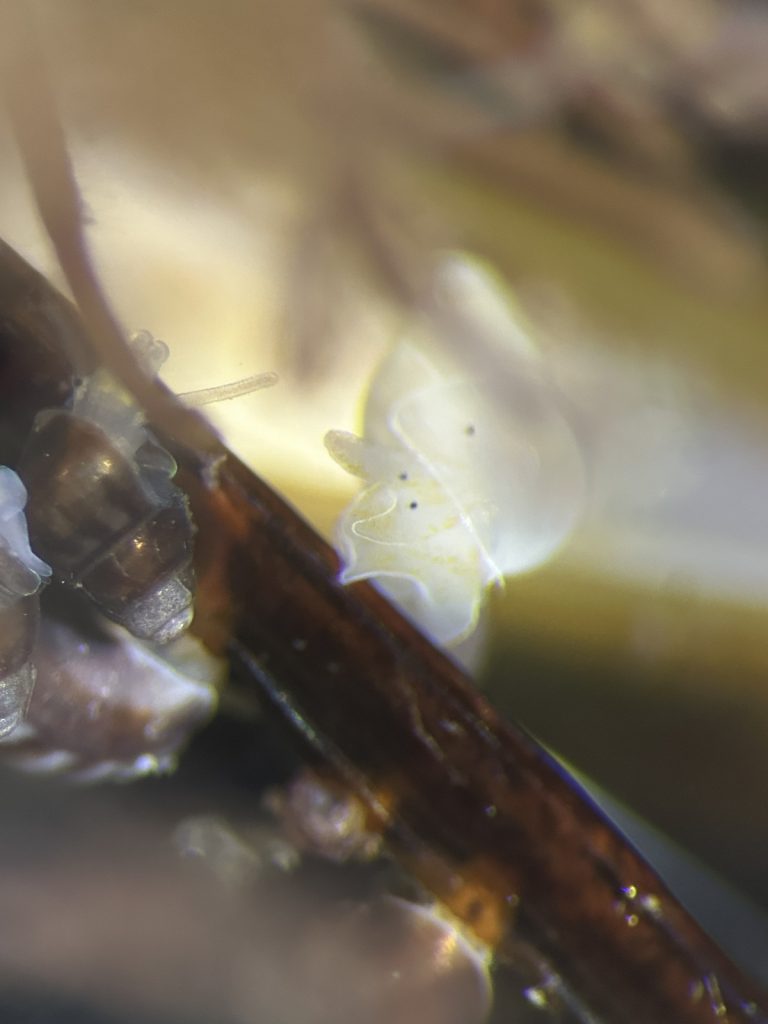

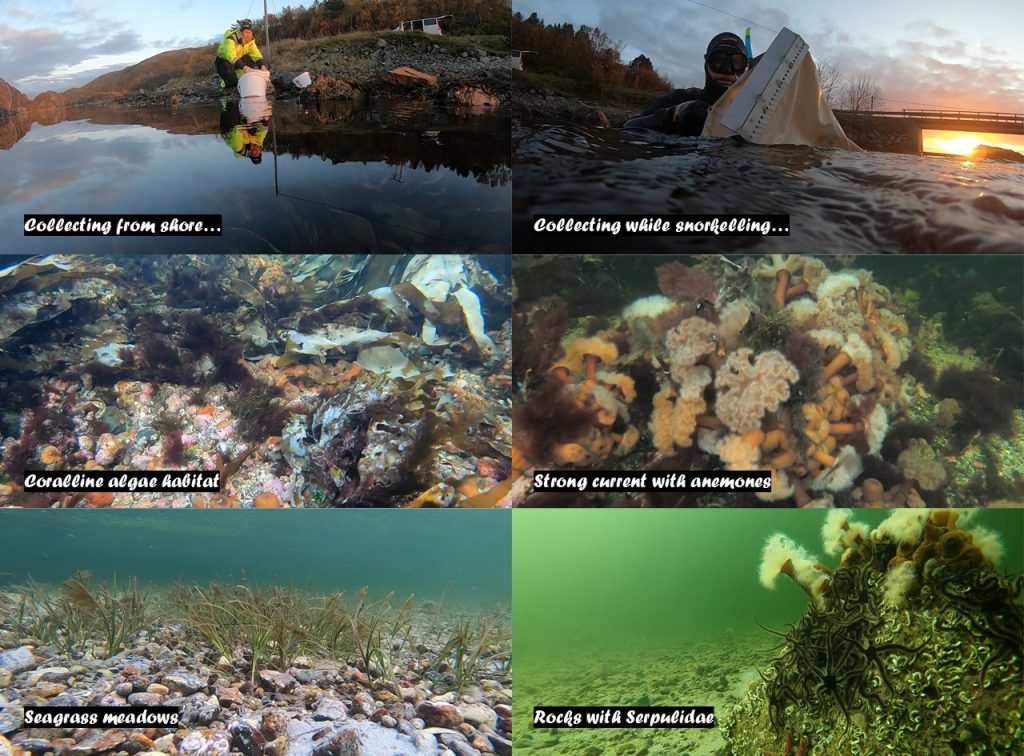

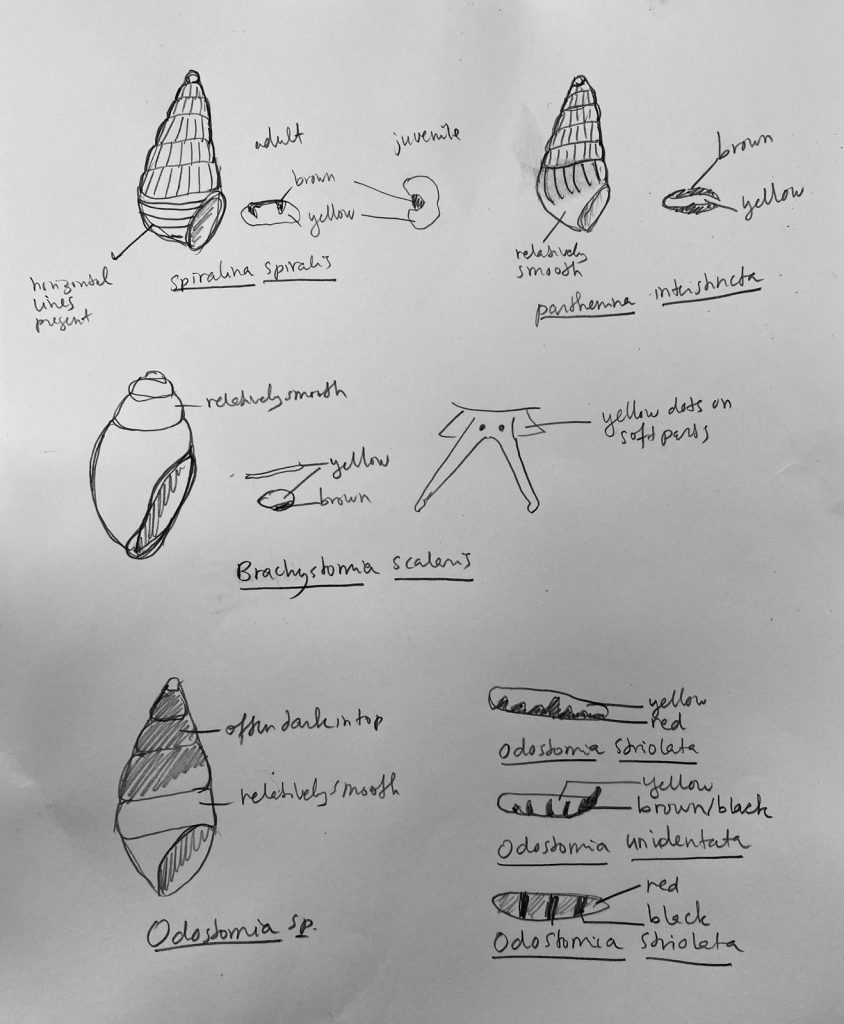

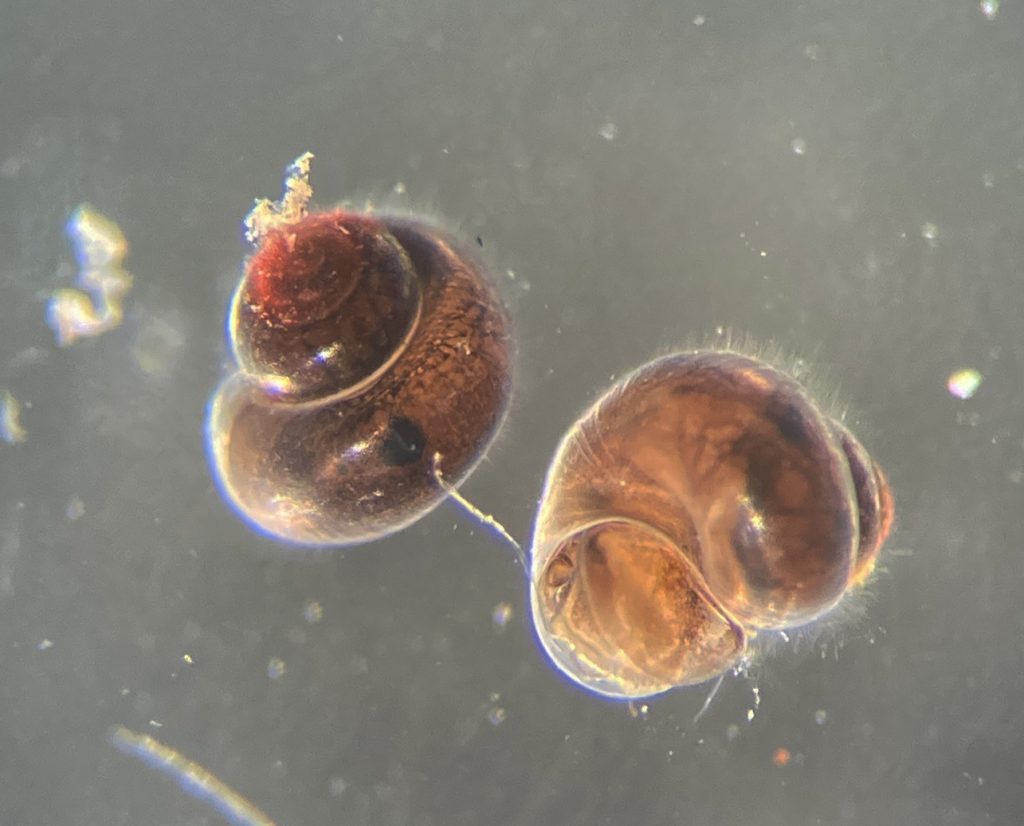

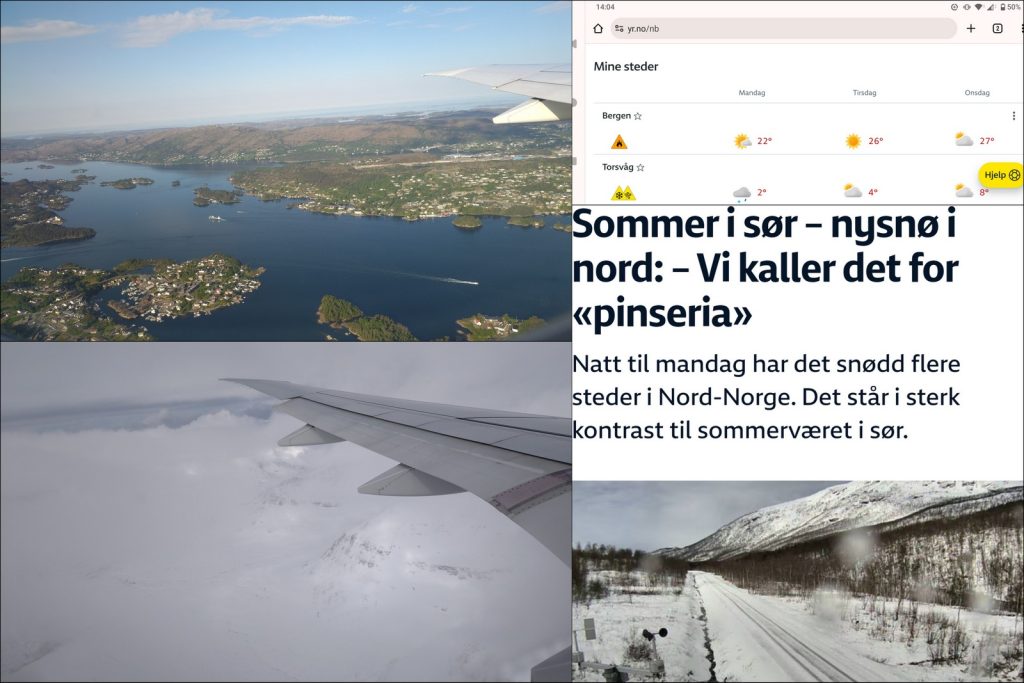

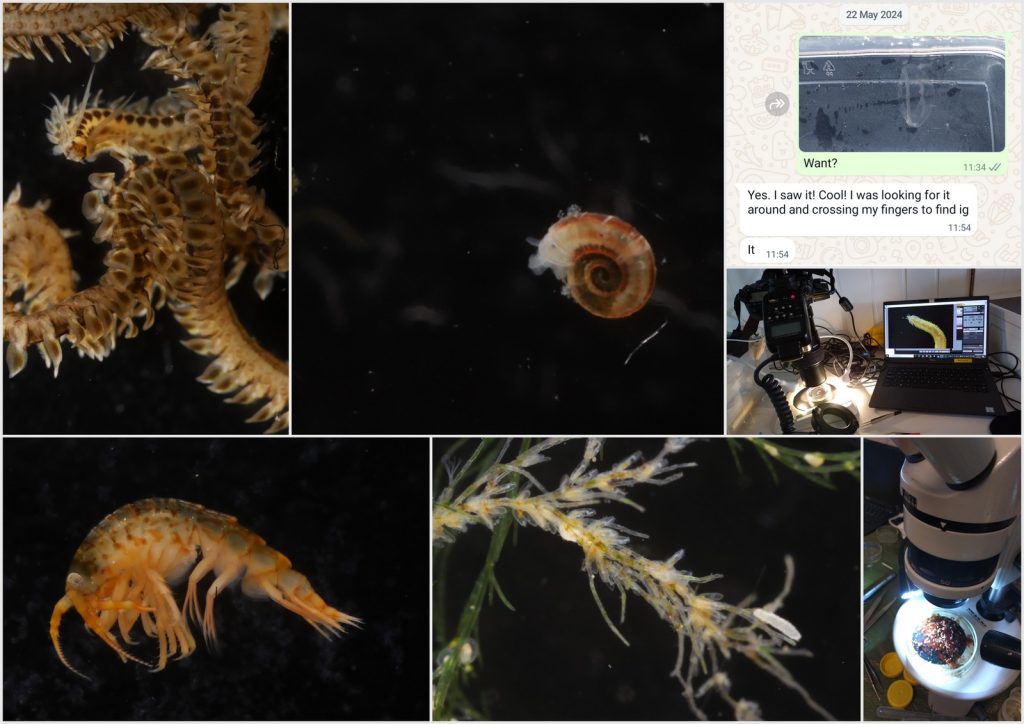

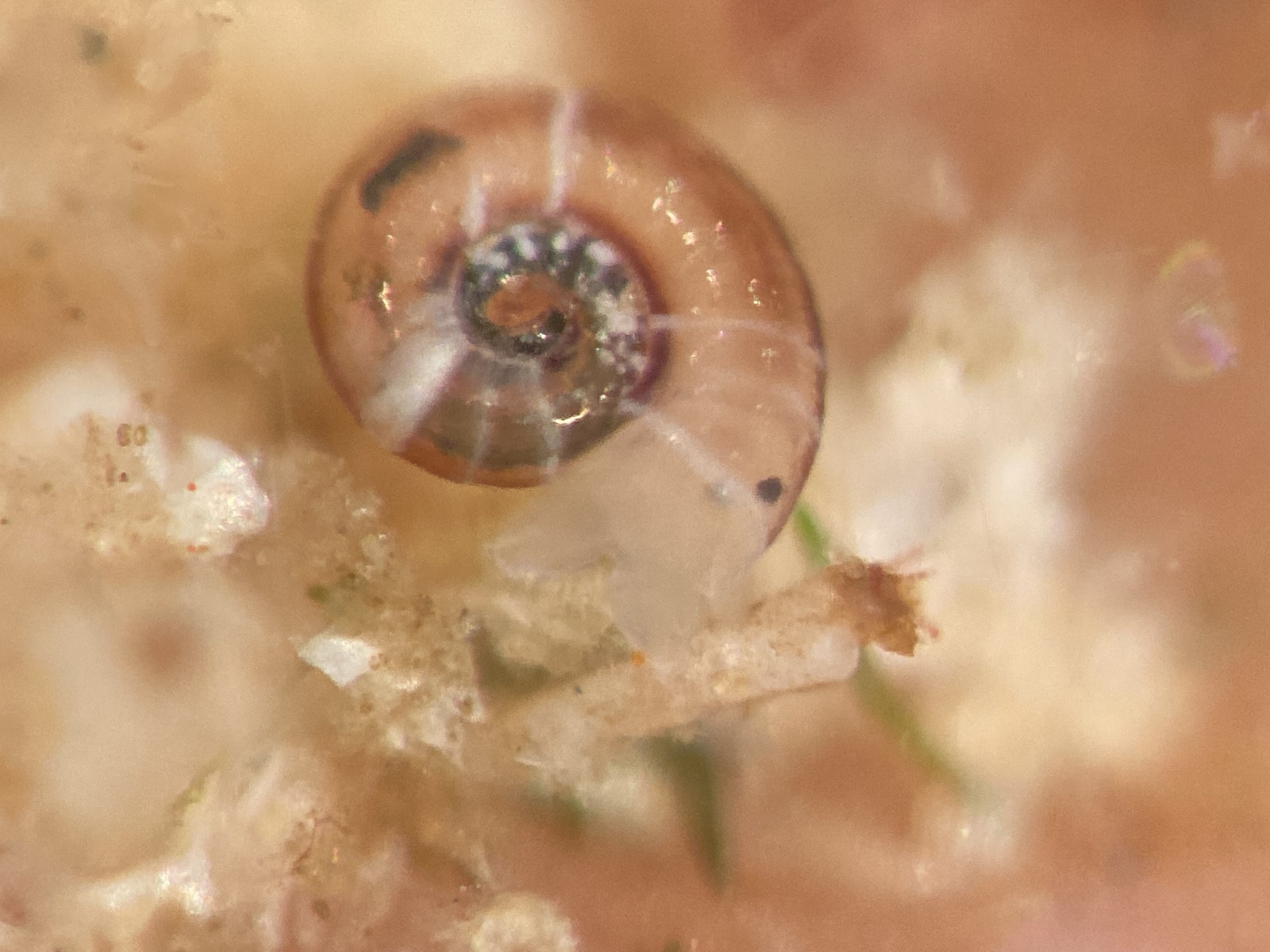

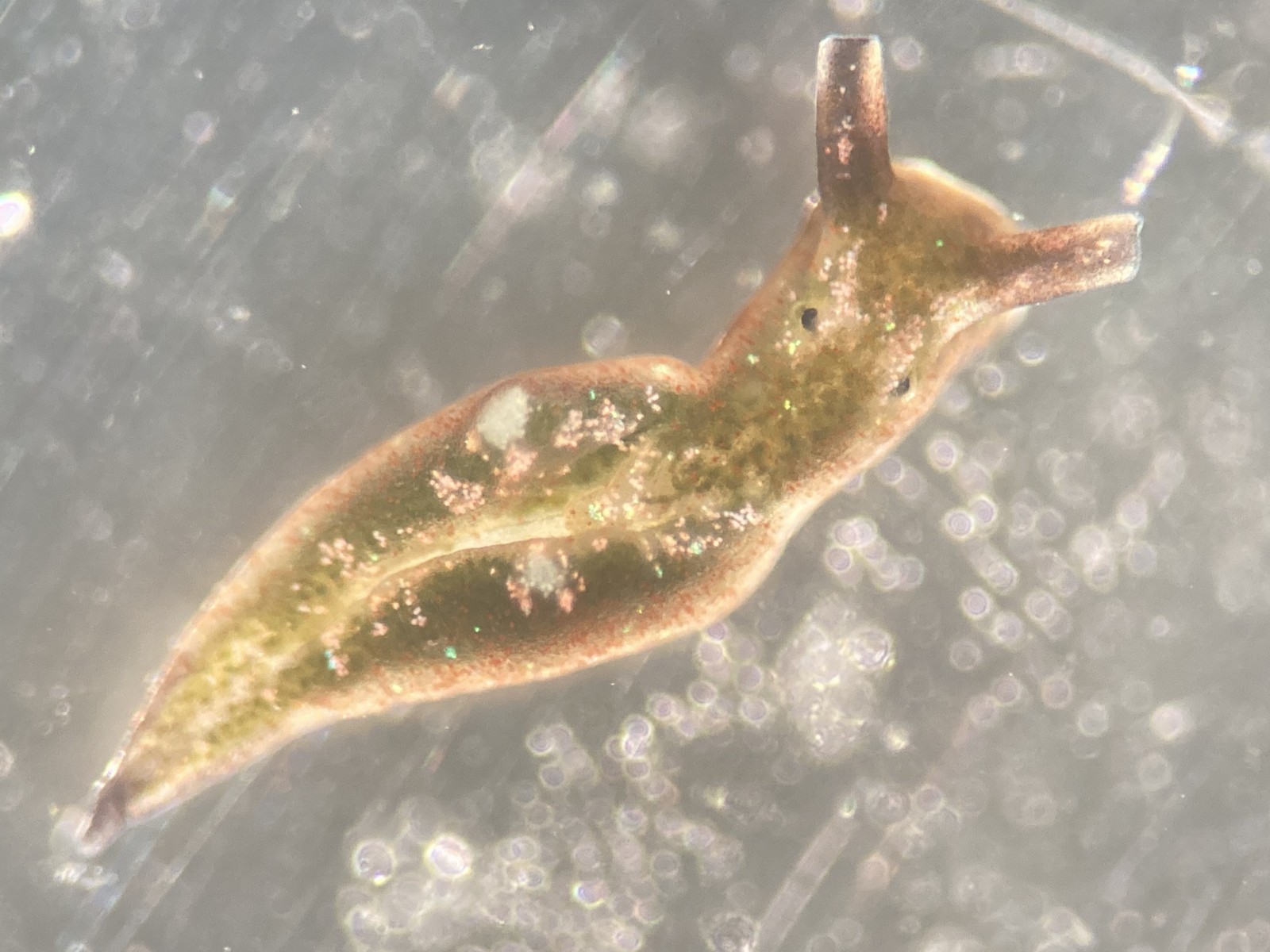

Lower heterobranchs and pyramidellids are among the most difficult marine gastropods to collect and identify. Their small shell size (1–3 mm), resemblance, specialized habitats, and the fact that many are ectoparasites of other marine invertebrates, create significant challenges. During a recent field trip to southern Norway, we registered for the first time a species of Brachystomia pyramidellid feeding on the blue mussel Mytilus edulis with its extended proboscis penetrating between the valves and sucking fluids from the bivalve tissue.

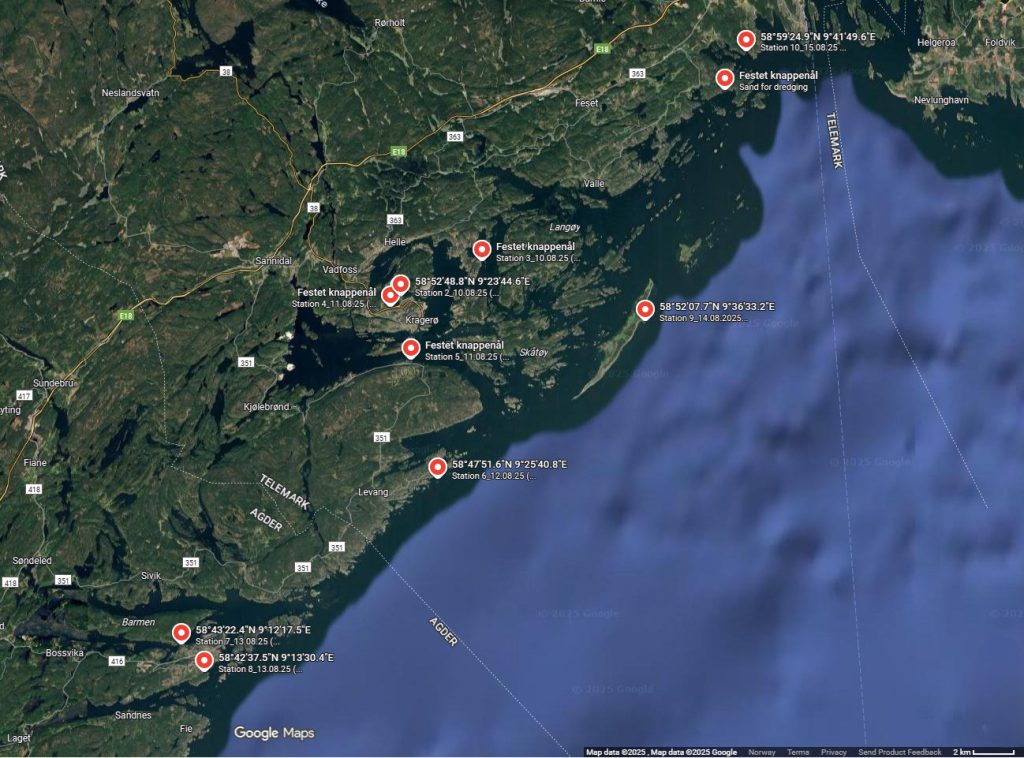

Since the beginning of the project in September 2023, efforts have focused on obtaining new samples suitable for DNA barcoding and documenting living specimens. A major component of the work has also involved the curation of the substantial collection housed at the University Museum of Bergen. Much of this material was originally assembled by Prof. Tore Høisæter during the 1970s, with important later contributions by Per Bie Wikander, particularly from southern Norway, and more recent additions through projects such as MAREANO and Hardbunnsfauna, the latter also funded by Artsdatabanken.

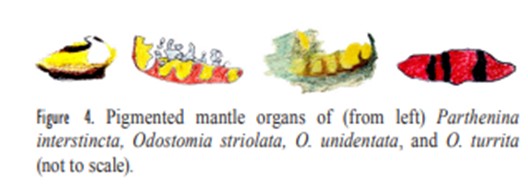

In August, we had the opportunity to present our first results at the World Congress of Malacology in São Paulo, Brazil. This presentation focused on a large DNA barcoding dataset comprising 164 sequenced specimens and explored the relationships among shell types, habitats, and body colouration.

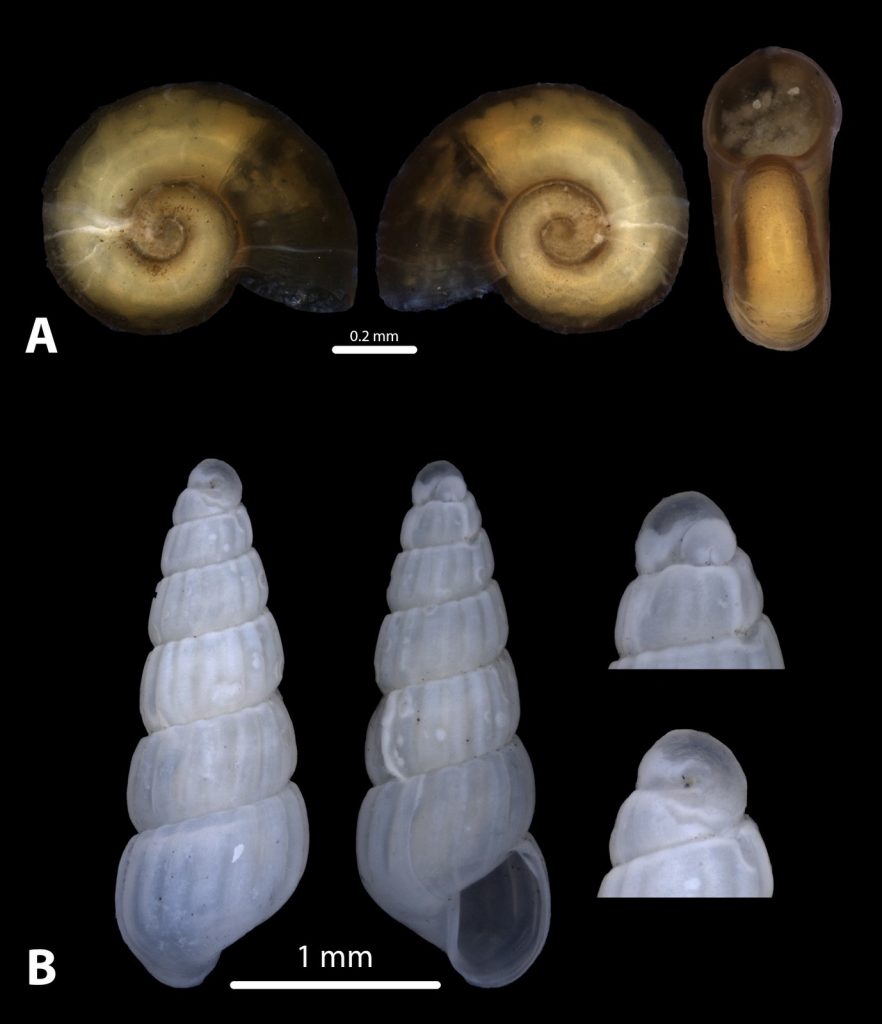

This phylogenetic framework formed the backbone of the workshop’s activities, supporting comparisons with our collections, revisions of previous taxonomic identifications, and the selection of additional material for further DNA sequencing and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). One morning of the workshop was dedicated to an SEM session in which we discussed and standardized imaging protocols for capturing detailed views of these minute shells, including protoconchs.

Among the immediate outcomes of the workshop was the recognition of genera and species new to Norway and potentially new to science—findings that will guide our research in the coming months.

We extend our sincere gratitude to all participants and colleagues whose support made the workshop possible. In particular, we thank our guest scientists, Dr Bastian Brenzinger and Dr Kennet Lundin, for generously sharing their expertise and contributing to a highly productive and enjoyable event.

This research was funded by the Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative, Artsdatabanken Project No. 70184245, grant 13-22 (Diversity of Heterobranchia gastropods in Norway with a focus on poorly known groups and habitats).

Cessa Rauch & Manuel Malaquias

Photo credits: KK: Katrine Kongshavn, CR: Cessa Rauch, MB: Monisha Bharate