Dr Joan Soto from the University of Valencia (Spain), visited us at the museum during August/September 2017 to collaborate with HYPNO on the mysterious issue of linking hydroids and their medusae. We asked him about his experience, and got the following:

Imagine a caterpillar and its butterfly described as different species by the scientific community. Now think on how confusing it would be if everybody kept calling them with different names over centuries. Well, this is the case of many hydroids and their corresponding medusae!

Hydrozoans, together with other well-known animals such as corals, anemones and jellyfishes, are included within the Phylum Cnidaria. Most hydrozoans are metagenetic, which means that they alternate between asexual (the polyp, usually benthic) and sexual (medusae, usually pelagic) stages in their life. Since the early works by Linnaeus in the mid-18th century, the very first scientists who showed interest in hydrozoans specialized primarily in a single stage of their life cycle, often neglecting the other, and even those courageous scientists who accepted the challenge of studying both groups were unable to discover the correspondence between such different animals as the polyp and the medusa.

Nowadays, in the era of molecular tools, new techniques are revealing that things are not what they seem, neither do they look like what they really are. Thanks to project HYPNO, several links between polyps and medusae have been found, with the subsequent adjustment in their ID (a.k.a. their scientific name), but that is not all! New evidences are bringing to light that some hydrozoans, even if they are morphologically identical to each other, in reality belong to different species, a fact known as “cryptic species”.

Both of these phenomena may be involved in the taxonomic confusion surrounding the hydroid Stegopoma plicatile and the medusa Ptychogena crocea, the former a worldwide reported species, the latter a Norwegian endemism. How can a medusa be so restricted in distribution while its hydroid lives everywhere? Perhaps now we know the answer thanks to molecular tools: Stegopoma plicatile may represent a complex of species, hiding a misunderstood diversity, and similar S. plicatile hydroids may produce different Ptychogena medusae. In other words, perhaps the polyp does not have such a wide distribution, and records from other parts of the world should be re-examined in detail, paying special attention to the tiniest and easily overlooked details of its morphology. But of course this is a job only for very patient detectives…

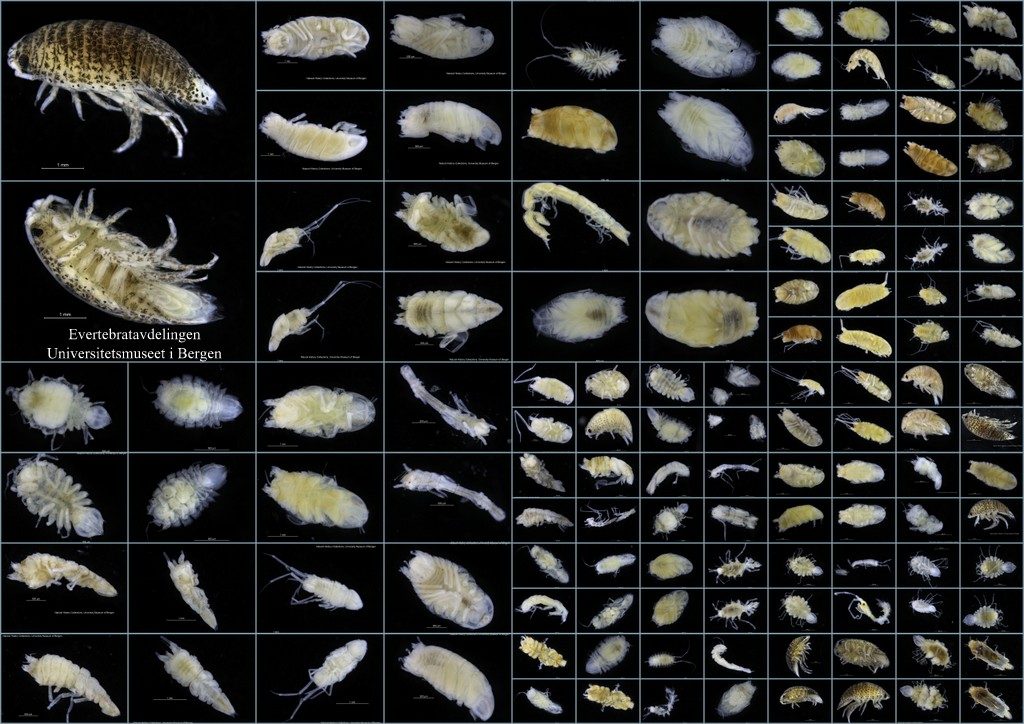

Hydroids of Stegopoma plicatile (like this one) from all over the world look very similar to each other, but may produce very different medusae.

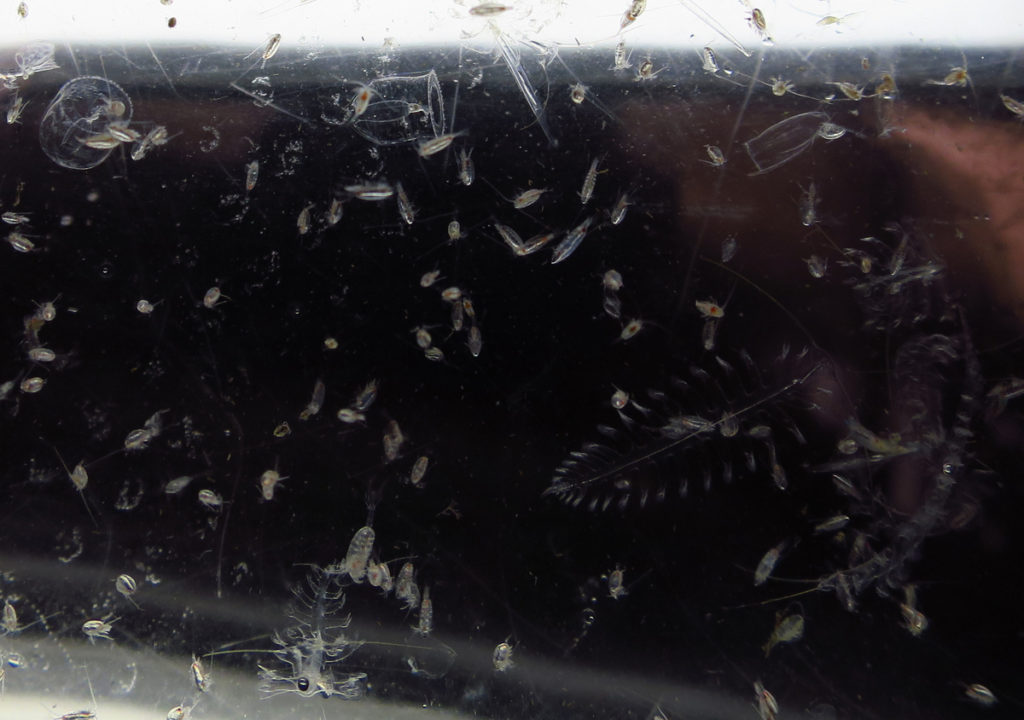

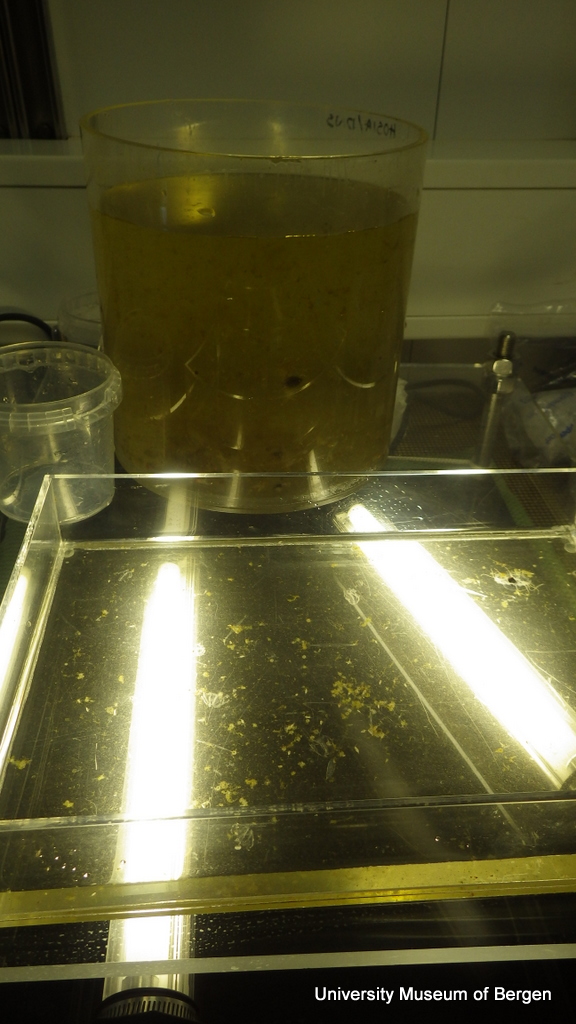

These beautiful medusae of Ptychogena crocea collected in Korsfjord were sexually mature. You can see the four gonads as folded masses of yellow tissue in each jellyfish.

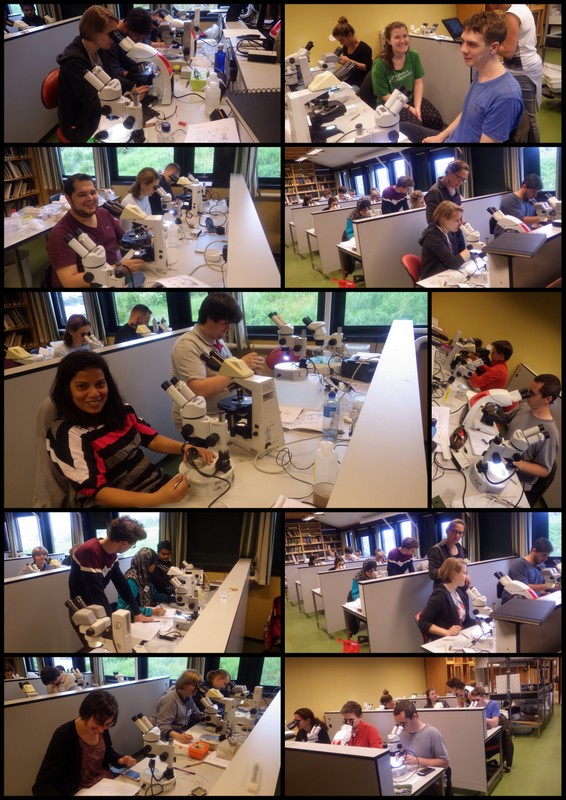

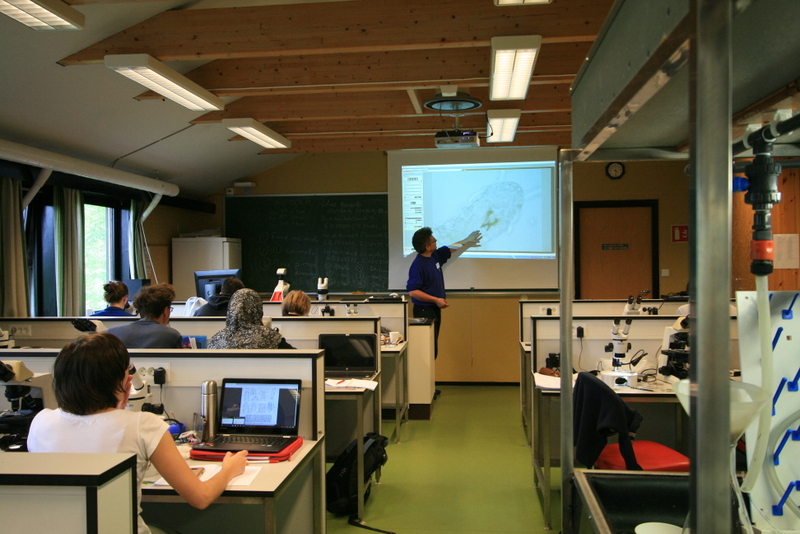

Thus, this was the objective of my recent visit to the Bergen University Museum. An outstanding month surrounded by enthusiastic scientists, amazing landscapes, restricted doses of sun, and upcoming challenges: we trust that current and future analyses combining both molecular and morphological taxonomy will lead to settle the correspondence of Stegopoma hydroids with other Ptychogena-like medusae from all over the globe, or even to the description of new species to science!

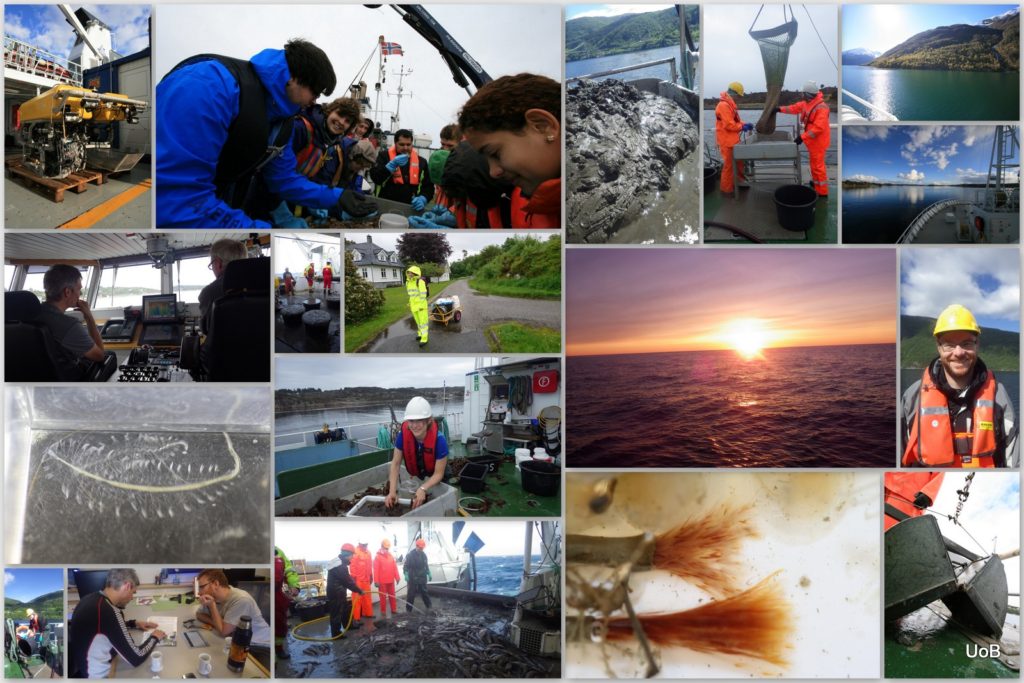

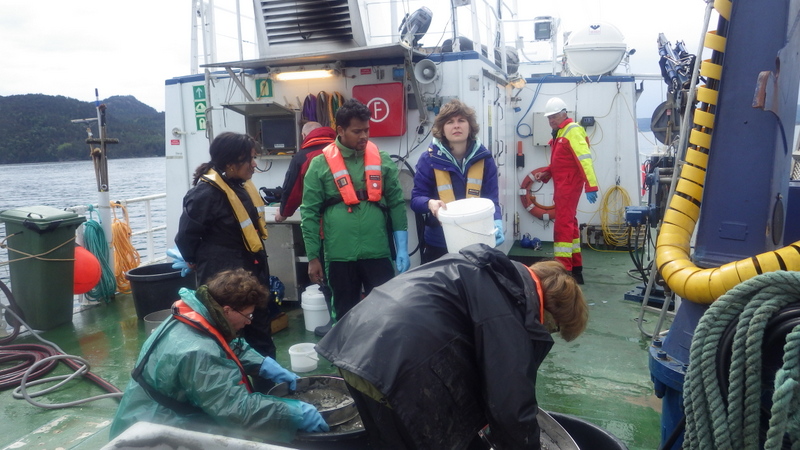

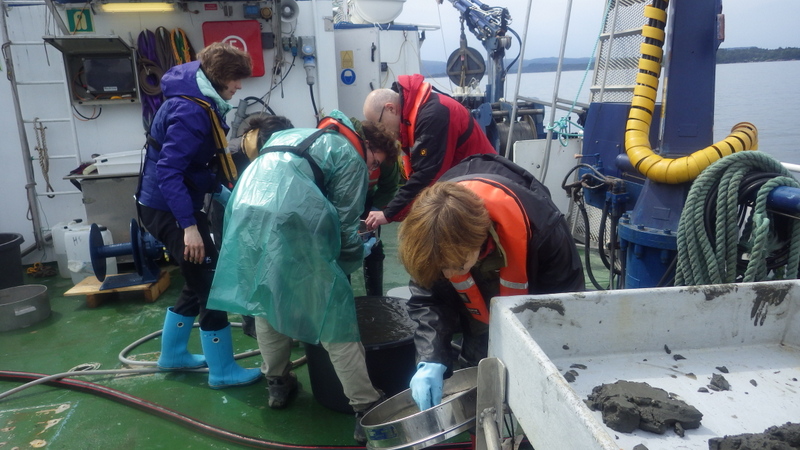

The amazing crane of the RV “Hans Brattstrøm” allowed us to efficiently hunt for jellyfish at the fjords.

-Joan