At first glance, it can look like a seaweed. The depth, however, should start your alarm-bells for flora and point you towards fauna: the plantlike animal Securiflustra securifrons (Pallas, 1766) is a bryozoa – a collection of colonial filterfeeders less than 1 mm in size each. We are at 80-120 m depth in the cold Heleysundet – the sound between the two islands Spitsbergen and Barents Island in the eastern part of the Svalbard Archipelago. This is a sound famous among captains for its fast tidal streams, and the fast-flowing waters give the bryozoans a nice place to live. The colonies branch out to catch the most water-flow and the most food from the water.

Where the “branches” form we see what might look like small hairy balls – these are the bivalve Musculus discors (L., 1767). The hairy look comes from their byssus threads – they produce and then use these threads to attach to the Securiflustra (and being packed in the threads they might get some camouflage from them).

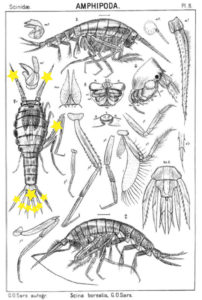

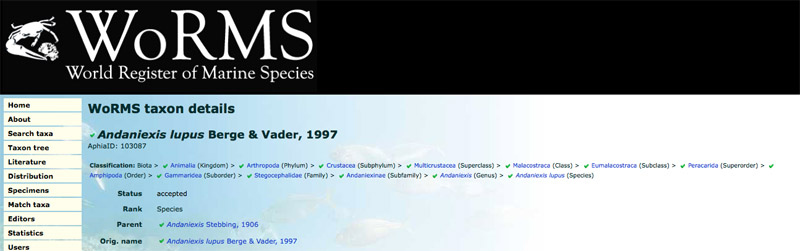

Moving inside the molluscs we might find not only one, but two species of amphipods. In our samples from Heleysundet 14% of the Musculus had the carnivorous amphipod Anonyx nugax Ohlin, 1895 inside, and an astonishing 3 out of 4 Musculus had amphipods of the species Metopa glacialis (Krøyer, 1842) inside. The system resembles a Russian doll – one species living inside another living inside yet another…

Anonyx affinis (large amphipod, upper left) and Metopa glacialis (small amphipod lower half og mussel) innside a Musculus discors. Photo: AHS Tandberg

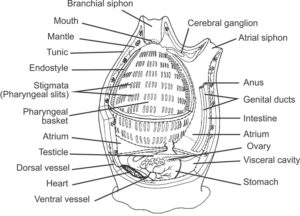

What reason can a small crustacean have to live inside the quite closed off world of a bivalve? The bivalve filters water actively – it pumps water over its gills, and then transports food-particles such as phytoplankton down the gills towards its mouth. Non-desirable particles are normally packed into mucus and transported out of the bivalve. Now imagine liking to eat some of those particles the bivalve finds non-desirable, and being placed on the gills of said bivalve. No need to hunt for the food – it will be coming on the conveyor-belt the gills are – and all you need to do is to eat. The bivalve does not seem to be troubled by this co-habitant – it does not eat the same food as the bivalve.

Not only does Musculus discors provide Metopa glacialis with food, the mantle cavity provides a luxury-shelter where the amphipod can raise a family! Amphipods, together with isopods, cumaceans, tanaidaeans and quite a few mysicadeans keep their offspring in a brood-pouch from the fertilisation of the eggs to the medium sized juveniles crawl out into the real world. Living inside a bivalve allows Metopa glacials to extend its child-care to young life outside the brood-pouch. Our examinations of the bivalves from Heleysundet showed us adult Metopa in the middle of the bivalve, with several juveniles “strategically placed” inbetween the two layers of gills in each shell-half. Surrounded by food, safe from most predators! (Predation of Metopa glacialis might be the main objective for Anonyx affinis, the food-source of the lysianassid needs to be established. It might also be the nice and fatty mollusk.)

- Adult male Metopa glacialis. Photo: F Pleijel

- Adult (and “pregnant”) female Metopa glacialis. Photo: F Pleijel

Metopa glacialis innside a Musculus discors. Small arrows point to juveniles, large arrow to adult female. Photo: AHS Tandberg

Comparing with amphipods of the same size-range from the same areas, Metopa glacialis seems to have a safe life. Safe enough that they can manage to have several sets of offspring. We see that they don´t wait until´the first batch of kids are out of the “house” – we found one adult female with two size-groups of offspring and a fresh egg-filled brood-pouch! Each batch can be 20 offspring, so that would mean one pregnant mom and 40 kids in one small house!

Many people travel to visit family during the holidays. Even when we cherish the time with our loved ones, filling the house with grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins might cramp everybodys style slightly. Not so with Metopa glacialis. Measuring the size of all inhabitants show us that the kids stay home until they are adult and can move out to their own home. So when you can´t sleep because your younger cousin plays on her gamer all night, or because your old aunt snores when you come into your shared room, think how much more difficult life could have been if you were an amphipod. Happy holidays!

Anne Helene

PS: A slightly extended version in Norwegian (part of the TangloppeTorsdag blog) can be read here)

Literature:

Just J (1983) Anonyx affinis (Crust., Amphipoda: Lysianassidae), commensal in the bivalve Musculus laevigatus, with notes on Metopa glacialis (Amphipoda: Stenothoidae). Astarte 12, 69-74

Tandberg AHS, Schander C, Pleijel F (2010) First record of the association between the amphipod Metopa alderii and the bivalve Musculus. Marine Biodiversity Records 3:e5 doi:10.1017/S1755267209991102

Tandberg AHS, Vader W, Berge J (2010) Studies on the association of Metopa glacialis (Amphipoda, Crustacea) and Musculus discors (Mollusca, Mytilidae). Polar Biology 33, 1407-1418

Vader W, Beehler CL (1983) Metopa glacialis (Amphipoda, Stenothoidae) in the Barents and Beaufort Seas, and its association with the lamellibranchs Musculus niger and M. discors s. l. Astarte 12:57–61