Scientific illustrations today are usually formed within quite strict limits. We use photographs or drawings of small details, and these are all connected to one specific specimen that preferably is to be found in a scientific collection.

But can other approaches also help us? The artist Pippip Ferner has long found her inspiration in nature, and especially the (marine) invertebrates. Maybe her pictures can inspire us to examine other details in our study-animals? Maybe a picture can inspire you to think more about nature, the sea, or invertebrates – their lives and lores? These are not pictures that are meant to be scientifically accurate, but rather fabulations inspired by the wild things that happen when evolution gets to do as it pleases…

Some of Pippis drawings are inspired from scientific drawings, both old and new, some are from animals we have looked at together.

Here are some of Pippips pictures from this year, and the animals that inspired them. These three pictures were chosen to be part of the Evolution and Art section of the international science conference Evolution this summer in Austin, TX.

Pippip says about this first picture:

“A scientific illustration of a TUNICATE is the inspiration for this work. Tunicates are sort of last stage before vertebrates. Clues for this is found in the larva that has a notochord, comparable to the spine of vertebrates. It has cerebral vesicle equivalent to a vertebrate’s brain, sensory organs that includes an eyespot to detect light and an otolith, which helps the animal orient to the gravity.

Fascinated by the thought of this “slimy blob” having many features similar to humans resulted in this quite complex outcome. The overload of insistent lines has given the tunicate quite a sophisticated system.”

On the left is a photo of a live tunicate. This photo is from Indonesia, but tunicates are common to find also in our colder waters. They can be solitary as this one, or colonial – where several tunicates form a colony together by budding, so that one large colony basically has the exact same DNA. Most tunicates are sessile (they sit attached to one place), but some live floating around in the water. The best known of these pelagic tunicates are the salps of the southern oceans.

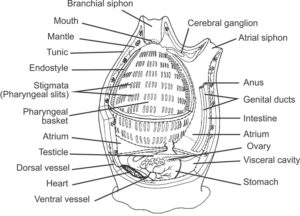

Internal anatomy of a tunicate (Urochordata). Adapted, with permission, from an outline drawing available on BIODIDAC. (Wikipedia)

A scientific illustration of a tunicate in a Biology textbook will look something like this:

Moving to other invertebrates, Pippip has worked with clams:

“In this image I question how the clam lives in symbiosis with other species as its shell gets weaker due to climate changes. The drawing might resemble the results of some kind of scientific inquiry with references to the anatomy of a clam (bivalve).

In my work I let my own artistic evolutionary process make the clam into something more abstract.”

(If you wait until door # 22, there might be a story that relates to bivalves that live with others…)

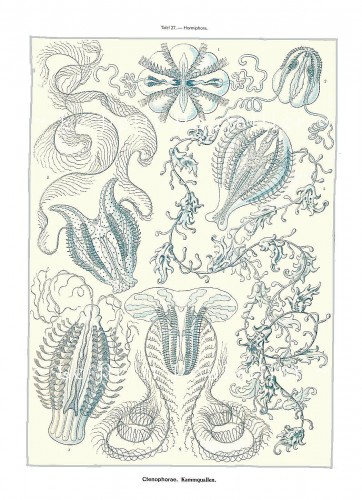

This is a Ctenophore, a comb jelly:

“The starting point of this work was a detailed illustration from biologist Ernst Haeckel’s (Artforms in Nature) of a comb jelly/ctenophorae. The comb jelly differs from other jellyfish with more sophisticated nervous system with both synapses and individual muscle cells.

The outcome of this drawing is a tribute to the beauty of the structure of this organism.”

- The comb jelly Pleurobrachia pileus. Photo: Aino Hosia

- The comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi. Photo: Aino Hosia

- The comb jelly Beroe abyssicola. Photo: Aino Hosia

Jelly fishes anf Comb jelly fishes. Illustration: Ernst Haeckel, Kunstformen der Natur 1904, plate 27

Ctenophores are predatory planktonic jellies. The special thing about them, according to our Jelly-specialist Aino, is that they have a rotational symmetry. The diagnostic feature of comb jellies are their comb-rows that they use for swimming. The photos above represent the three groups of comb jellies – all of them are present in Norway.

To the right is the Haeckel-picture she started from, and here is a film of Comb jellies from the Chicago Shedd Aquarium.

Pippip, Anne Helene and Aino