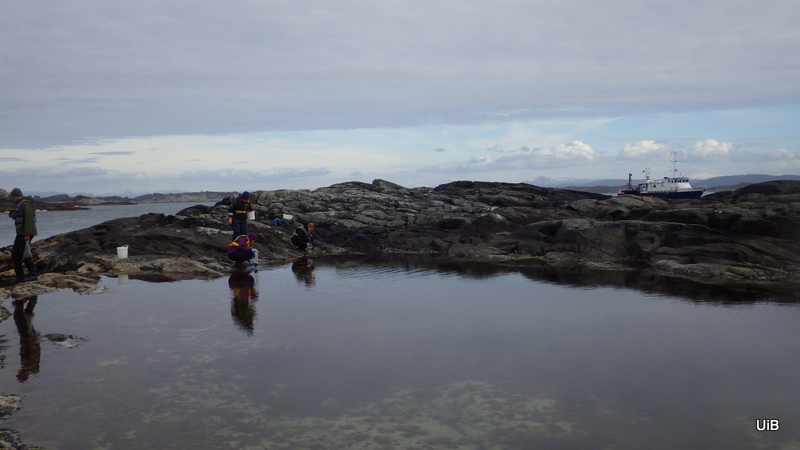

As mentioned earlier in our calendar, we have an extensive cooperation going on with the seabed mapping programme MAREANO*. You can read a lot more about MAREANO on the project home page, where you will also find many interesting videos and beautiful photographs from – quite literally – the bottom of the sea, as video transects are extensively used for mapping the sea floor and its biodiversity.

MAREANO very recently published a book named “The Norwegian Sea Floor – New Knowledge from MAREANO for Ecosystem-based Management”. As it presents the uniquely detailed mapping that is being carried out, it has received much attention (also internationally, more about that here and here (in Norwegian)). You can access the book as a pdf though the MAREANO web pages – check it out!

MAREANO very recently published a book named “The Norwegian Sea Floor – New Knowledge from MAREANO for Ecosystem-based Management”. As it presents the uniquely detailed mapping that is being carried out, it has received much attention (also internationally, more about that here and here (in Norwegian)). You can access the book as a pdf though the MAREANO web pages – check it out!

We wanted to include a post in our advent calendar about the part the University Museum plays regarding the thousands and thousands of biological samples that MAREANO generates. The MAREANO material is a big part of our everyday work here, and so it’s been blogged about before: follow the links to learn more our about cruise participation, workshops (e.g. here and here), new species described from UM based on MAREANO-material, and genetic barcoding through the Norwegian Barcode of Life (NorBOL) project.

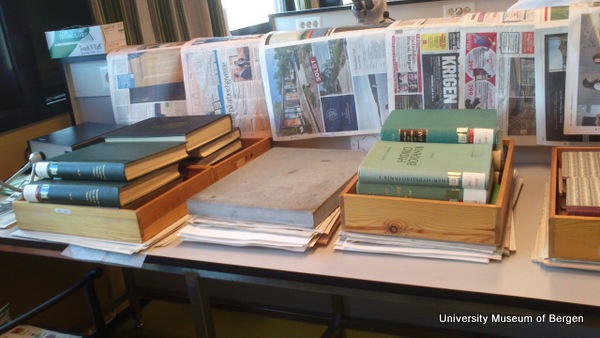

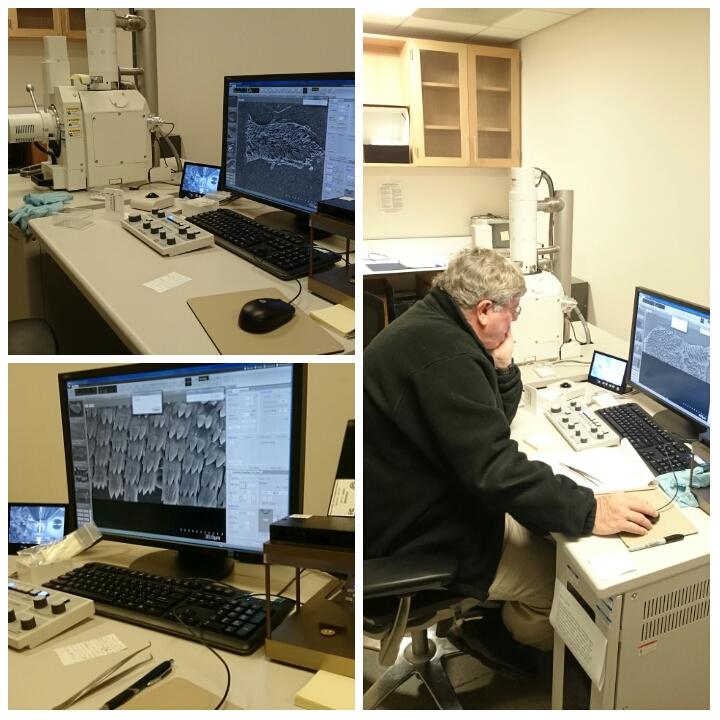

Workshop on the MAREANO-sponges

From a workshop on Cumacea (Crustacea) collected by MAREANO – it was late in December, so of course we had to make gingerbread critters (that could be identified to genus or species level..!)

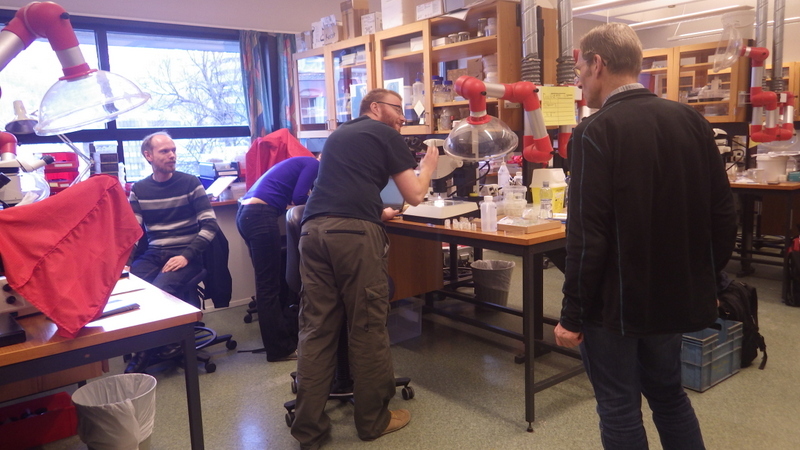

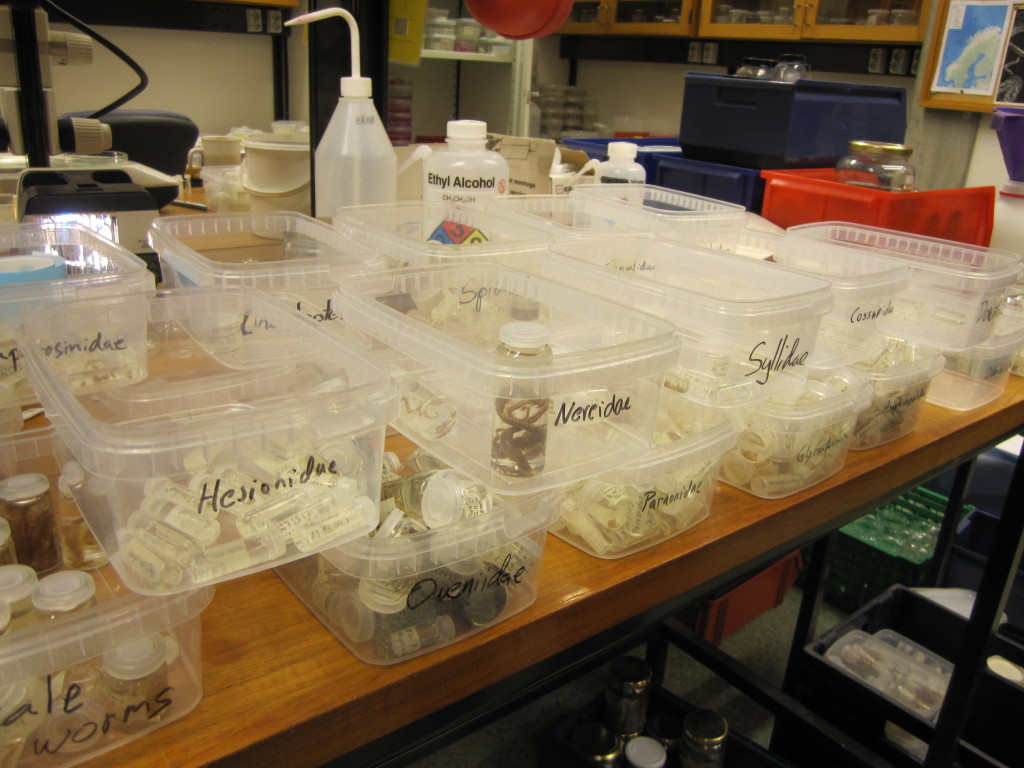

Snaphshot from one of the workshops during the project “Polychaete diversity in Norwegian Waters” (PolyNor), which has been working a lot on MAREANO-collected material

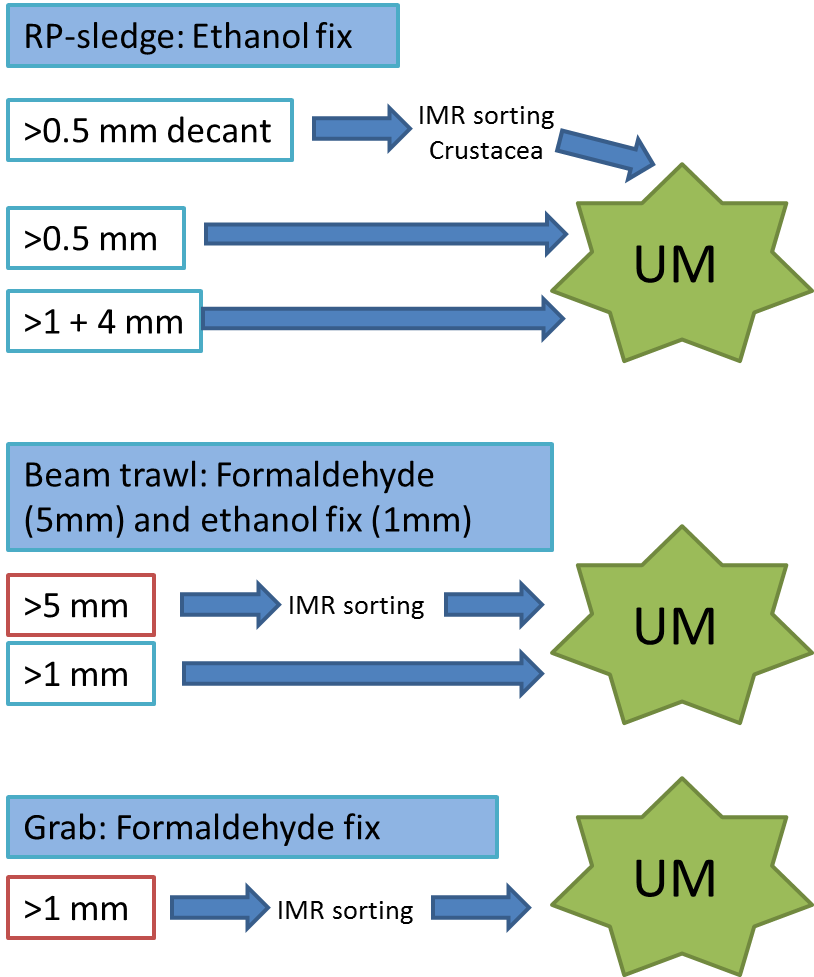

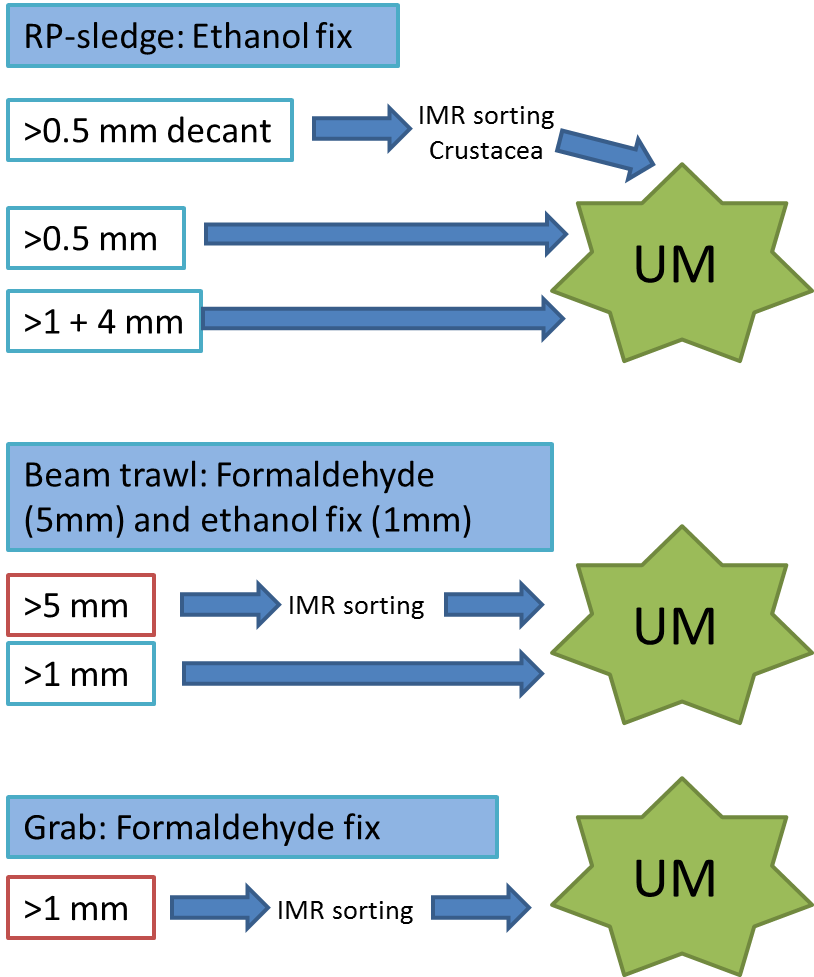

Every station with physical biological sampling typically includes two grab samples, one or two RP-sledge drags, and one beam trawl. Combined with video and all sorts of geological and chemical data collected, this gives us a thorough insight to the biodiversity at the location. The samples collected by different gears are naturally also treated differently; you can see how they are split up in this figure:

IMR = Institute of Marine Research (Havforskningsinstituttet)

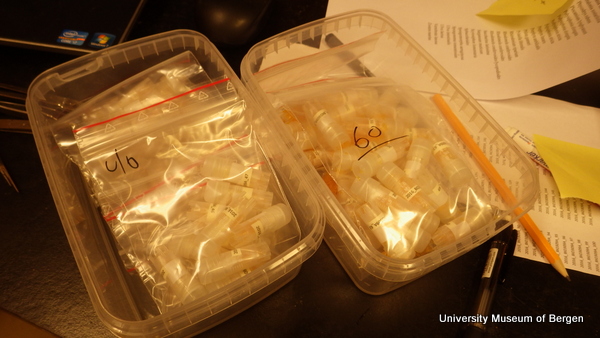

Now, any project – even one as extensive as MAREANO – does have a finite life span, whereas museum collections are (at least in theory) here for “eternity”. This means that we have to try and envision what material will be important not just right now, but also in the future – whilst we simultaneously deal with the constraints of limited time and space. It is not feasible to keep everything, but we do try our best to make sure that we keep that which is most important. The fact that MAREANO collects material not only in formalin (good for morphological studies), but also in ethanol (which – unlike formalin – enables us to do genetic analysis) is hugely important as we get the best of both worlds delivered – by the pallet!

Pallets of material

Buckets and buckets with sediment and animals

Filling up the car with precious cargo

Sorting the bulk fractions by station until we process them

Once we receive a shipment of material, we get to work – the identified animals are unpacked, and an assessment is done on how to proceed with them; catalogue them into the museum collection, interim catalogue them into our “project catalogue”, leave them untreated for now, catalogue and pass it on to researchers working on that particular group of animals, to include it in our current projects, or discard it.

The unsorted fractions require even more TLC; the first step is for us to separate the animals from the sediment – from there on it goes through much the same process as the identified critters. These unsorted (and mostly ethanol-fixed) samples have yielded many interesting finds, and will undoubtedly continue to do so! We have so far submitted over 1300 specimens collected by MAREANO to be DNA-barcoded through the NorBOL project, and this number will continue to rise.

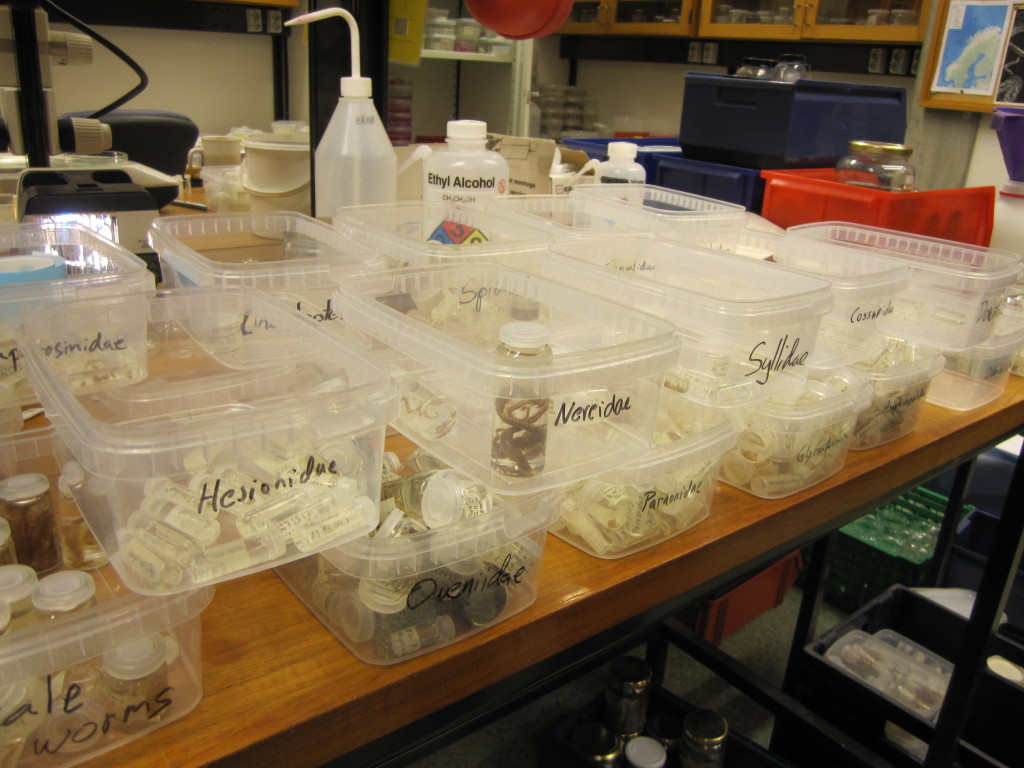

Sorting identified polychaete samples to family before storage

Guest researchers come to work on the material, here is Julio from Spain, who examined bristle worms from the family Oweniidae

But why do we need to keep all this material? Isn’t it “done” once MAREANO has done their identification of the fractions that they process? Of course not!

This material is a veritable gold mine for scientists, and it keeps on giving; MAREANO in it self aggregates a huge amount of interesting data (see here, for instance).

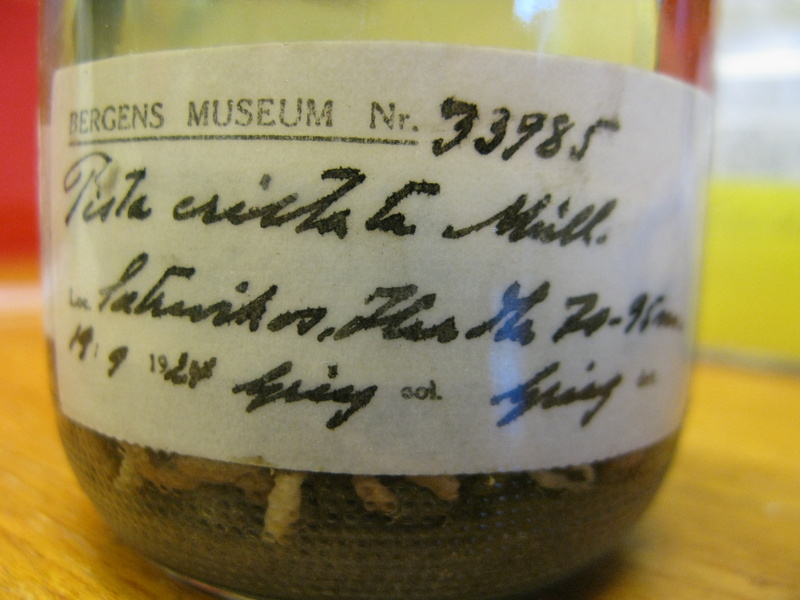

However, there are still many animal species groups that are extremely difficult to identify and when specialists on specific groups get the chance to compare specimens from different regions of the world, they very often find that original taxonomic identifications have to be revised. There are many reasons for that. Specimens may simply be misidentified. The revising taxonomist may also discover that specimens of the same species are called with different names in different laboratories. With applications of DNA-techniques it may also became apparent that what was originally considered to be one widespread species is actually several different species that have to be described and named.

So there are at least two main reasons why museums are eager to access and store material from projects like MAREANO and MIWA. One is the fantastic opportunity to get fresh specimen for research. Another reason is to safeguard and document the physical objects that the data were based on and to offer open access to study the specimens for the scientific community of researchers in biodiversity. Taxonomic studies may take a lot of time to complete, and taxonomists are scarce – so new results will continue to emerge at erratic intervals.

Ampharete undecima. Photo: K. Kongshavn

Thus the collected material is – and will continue to be – invaluable to scientific community for many, many years to come. There are still many new species waiting to be discovered (such as the little polychaete Ampharete undecima (Alvestad et al 2014), or the Amphipod Halirages helgae (Ringvold & Tandberg 2014), and there is much, much more to be learned about the distribution, habitats and life history of the species that we do know.

Therefore we are both proud and grateful to play a part in the safekeeping of this valuable material, and hope that it will continue to bring exciting new knowledge!

References:

Alvestad T., Kongsrud J.A., and Kongshavn , K. (2014) Ampharete undecima, a new deep-sea ampharetid (Annelida, Polychaeta) from the Norwegian Sea . Memoirs of Museum Victoria 71:11-19 Open Access.

Ringvold, H & Tandberg, A.H. (2014) A new deepwater species of Calliopiidae, Halirages helgae

(Crustacea, Amphipoda), with a synoptic table to Halirages species from the northeast Atlantic http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.98

-Katrine & Endre

(*For those wondering: MAREANO is short for Marine AREAl database for NOrwegian sea areas)

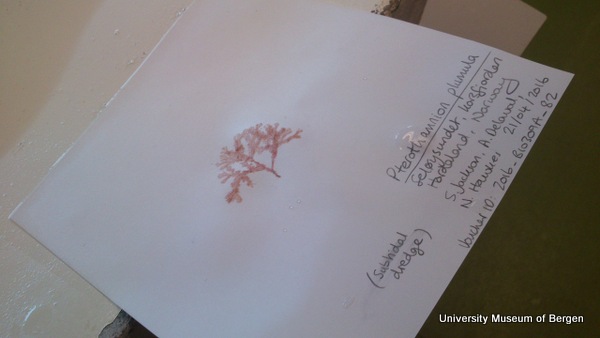

This specimen was collected by the R/V “Dr. Fridtjof Nansen” and has been identified as part of our MIWA – Marine Invertebrates of Western Africa – project. We’re working on a poster on the diversity of Glyceridae and Goniadidae of the region that will be presented at the 12th International Polychaete Conference in Wales this summer.

This specimen was collected by the R/V “Dr. Fridtjof Nansen” and has been identified as part of our MIWA – Marine Invertebrates of Western Africa – project. We’re working on a poster on the diversity of Glyceridae and Goniadidae of the region that will be presented at the 12th International Polychaete Conference in Wales this summer.