The participants of “ForBio Marine Course Greenland” represent a highly diverse group. This is our presentations of ourselves through our favourite organisms (“things”):

Near the end of the Greenland Adventure, full of unforgettable experiences and close to collapse of exhaustion after long days of sampling and sorting, our Arctic explorers took a few minutes of their precious time to write about themselves and which organism made them head North, up till latitude 69 degrees.

Andreas Altenburger (University of Copenhagen):

Andreas Altenburger (University of Copenhagen):

The aim of my project is to investigate the embryonic development of animals in the phylum Kinorhyncha. During the course I use the possibility to collect several kinorhynch species and try to make them reproduce.

Anne Helene Tandberg (Institute of Marine Research, Tromsø):

Amphipods from the genus Metopa are my favourite animals. This is a photo of Metopa alderi, who, just like its “cousin” Metopa groenlandica has been found here; they both live inside mussels. I love the way the tiny details help us determine which species we look at, and that they have found such clever ways of living – nice and cozy inside another animal…

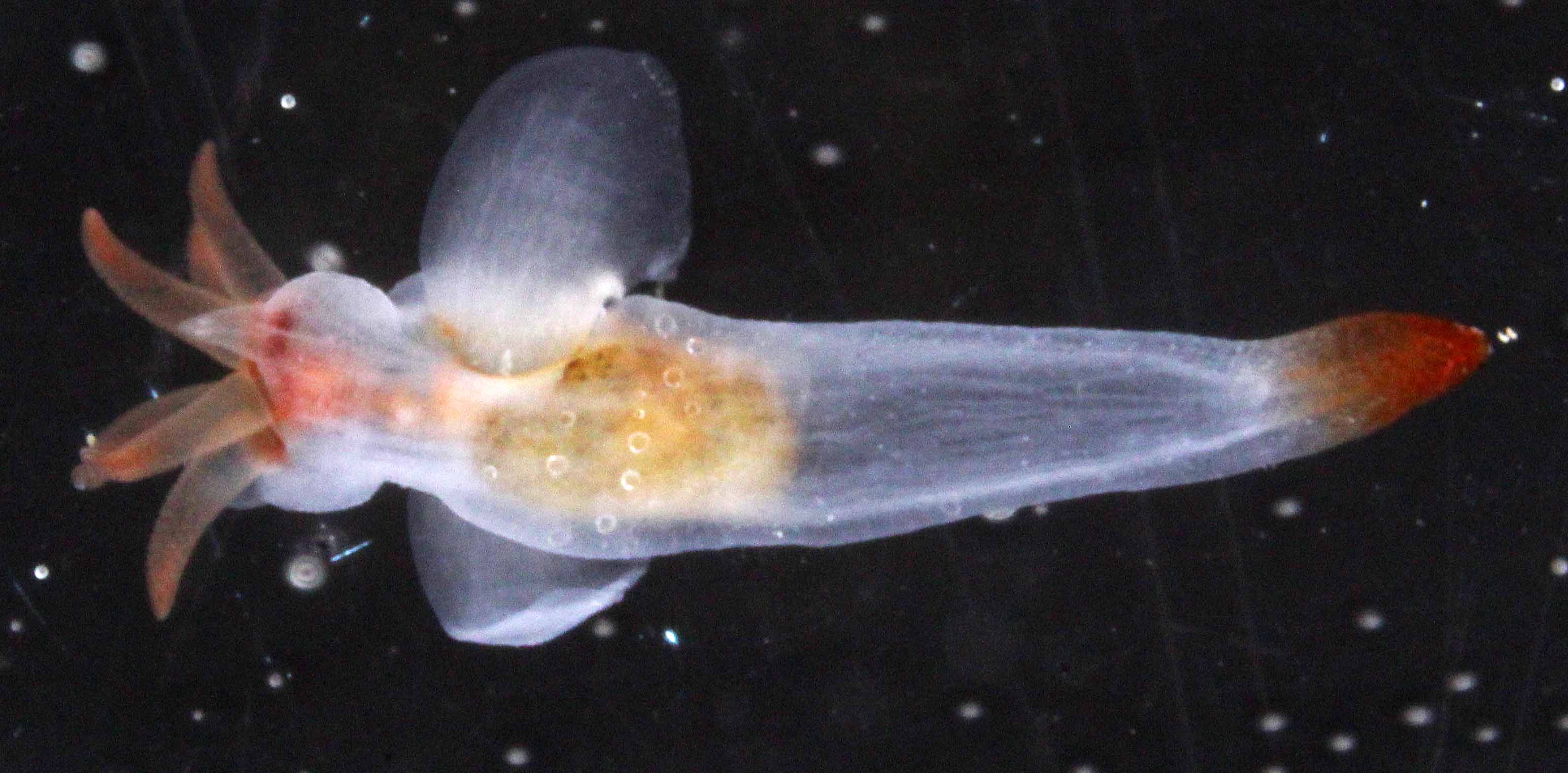

Christiane Todt (University Museum of Bergen):

My special interest are molluscs, and especially the shell-less and worm-shaped aplacophoran groups. The small solenogaster (or neomeniomorph) on this picture has already gained some fame in 2011 by being featured as “Greenland neomeniomorph” in a publication in the journal Nature (480: 364–367) – but it has no valid name yet! We found 10 more specimens – enough to analyze its anatomy and spicule morphology to come up with a proper species description and a scientific name!

My special interest are molluscs, and especially the shell-less and worm-shaped aplacophoran groups. The small solenogaster (or neomeniomorph) on this picture has already gained some fame in 2011 by being featured as “Greenland neomeniomorph” in a publication in the journal Nature (480: 364–367) – but it has no valid name yet! We found 10 more specimens – enough to analyze its anatomy and spicule morphology to come up with a proper species description and a scientific name!

Daniela de Abreu (University of Gothenburg):

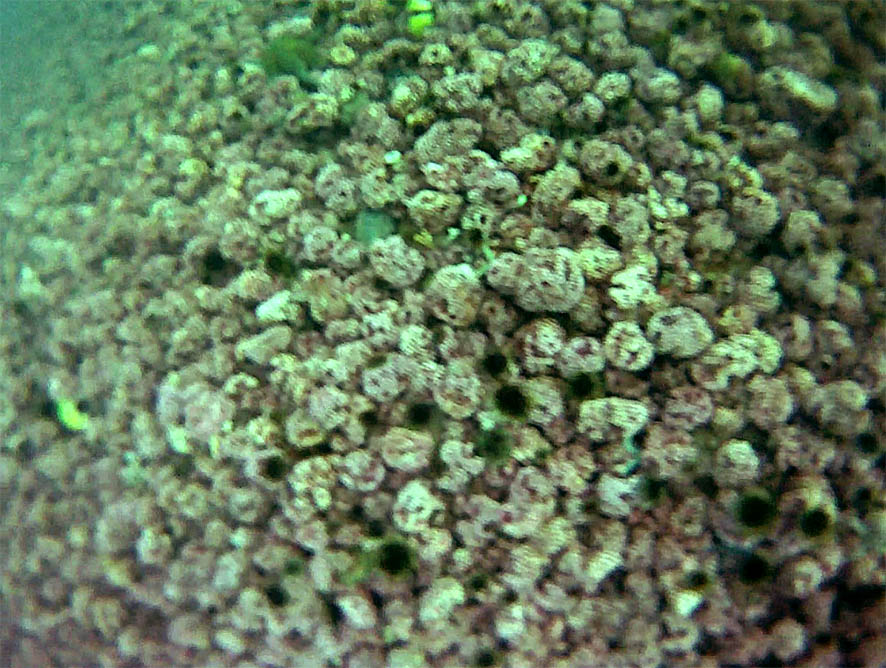

Yes! Slow moving amphipod. My favorite animal, so far, is Socarnes vahlii, the cutest, most colorful, and slowest amphipod I spotted on the Lithothamnion aggregation samples of Disko Fjord. This guy has the most amazing chromatophore patterns and colors of the crustaceans collected in this trip.

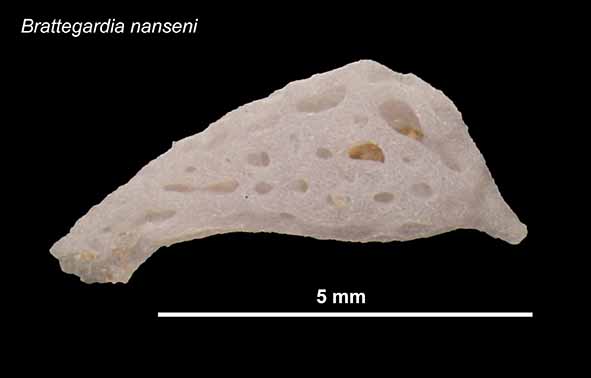

Henning Flørenes (University of Bergen):

Here on Greenland we’ve had a great variety of fauna that are absolutely fascinating. I’m currently working with calcareous sponges that are as amazing as anything you can imagine. My personal favorite is the fabulous Brattegardia nanensi. With its elegant form and lovely network of asconoid tubes, it ranks as the top sponge on my favorite list. It’s known to be around the Disko Island area so I’ve had the great opportunity to get a specimen and take a closer look at it.

Inga Meyer-Wachsmuth (Stockholm University):

My favorite animal didn’t show up, but there were a few close relatives that were unexpectedly colorful. This is a possibly undescribed species of Acoela of less than a mm length, with a beautiful red coloring. It was found with the Lithothamnion aggregations.

My favorite animal didn’t show up, but there were a few close relatives that were unexpectedly colorful. This is a possibly undescribed species of Acoela of less than a mm length, with a beautiful red coloring. It was found with the Lithothamnion aggregations.

Jakob Thyrring (Aarhus University):

I am working with blue mussels as they are ecological important species. I will investigate how this species that are susceptible to expand their current distribution range will influence the Arctic ecosystem structure and function.

Jenny Egardt (Gothenburg University):

I am a PhD student working with biodiversity and habitat change as a measurement of human impact in shallow marine coastal areas. In Disko, I am interested in learning more about arctic species and their abundance, and compare video footage taken during this course with footage from two years ago to see if the habitats are still the same.

Jeroen Brijs (Gothenburg University):

I’m doing a PhD on gastrointestinal motility and blood flow in fish, specifically shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius). I have captured a few here in Greenland to examine their stomach contents to determine what prey species they feed on so that I have a better understanding of their feeding ecology as this will assist me in understanding the digestive processes which occur within this fish species.

I’m doing a PhD on gastrointestinal motility and blood flow in fish, specifically shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius). I have captured a few here in Greenland to examine their stomach contents to determine what prey species they feed on so that I have a better understanding of their feeding ecology as this will assist me in understanding the digestive processes which occur within this fish species.

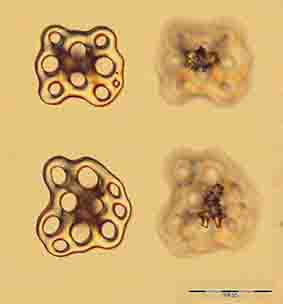

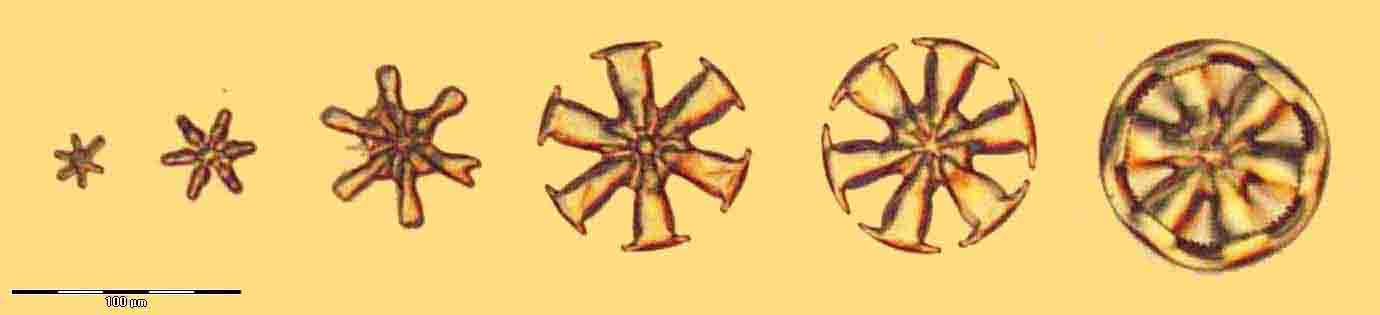

Josefin Sefbom (Gothenburg University):

I am investigating population genetic patterns of the diatom Skeletonema marinoi – a common and important bloom-forming primary producer found in many coastal waters.

Mari Heggernes Eilertsen (University of Bergen):

For my PhD I will be working on several different animals, but at the moment my favorite animal is a small calcareous sponge called Sycon abyssale, which is found in the deep North Atlantic and Norwegian Sea. Interestingly it is also found in shallow waters (<100 m) in Norwegian fjords, and I will use genetic analyses to establish if these populations are the same species and investigate the geneflow between populations, especially across the Greenland-Iceland-Faroes ridge, which is believed to be a major barrier to dispersal for deep-sea organisms.

Mette Møller Nielsen (Aarhus University):

I am a PhD student from Aarhus University, Denmark working with kelps. Kelps are widely distributed and highly productive and they are important organisms in coastal zones where they form key habitats. They act as substrate for sessile organisms as well as shelter and nursery area for fauna in general, thereby stimulating biodiversity.

I am a PhD student from Aarhus University, Denmark working with kelps. Kelps are widely distributed and highly productive and they are important organisms in coastal zones where they form key habitats. They act as substrate for sessile organisms as well as shelter and nursery area for fauna in general, thereby stimulating biodiversity.

Arom Mucharin (Aarhus University):

This small (ca. 3mm long) juvenile of Cucumaria frondosa (Gunners, 1767) we found in the Lithothamnion samples is really cool! I have been working with sea cucumbers in Thailand and in Denmark for some time now, but usually the specimens I deal with are much larger!!!

Peter Funch (Aarhus University):

The penis worm Priapulus caudatus from the mud outside the habour of Qeqertarsuaq (Godhavn), Greenland, was one of the best finds of this course for me. Together with my students in Aarhus I investigate symbiotic bacteria that live in the gut of these creatures.

Peter Kohnert (Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich):

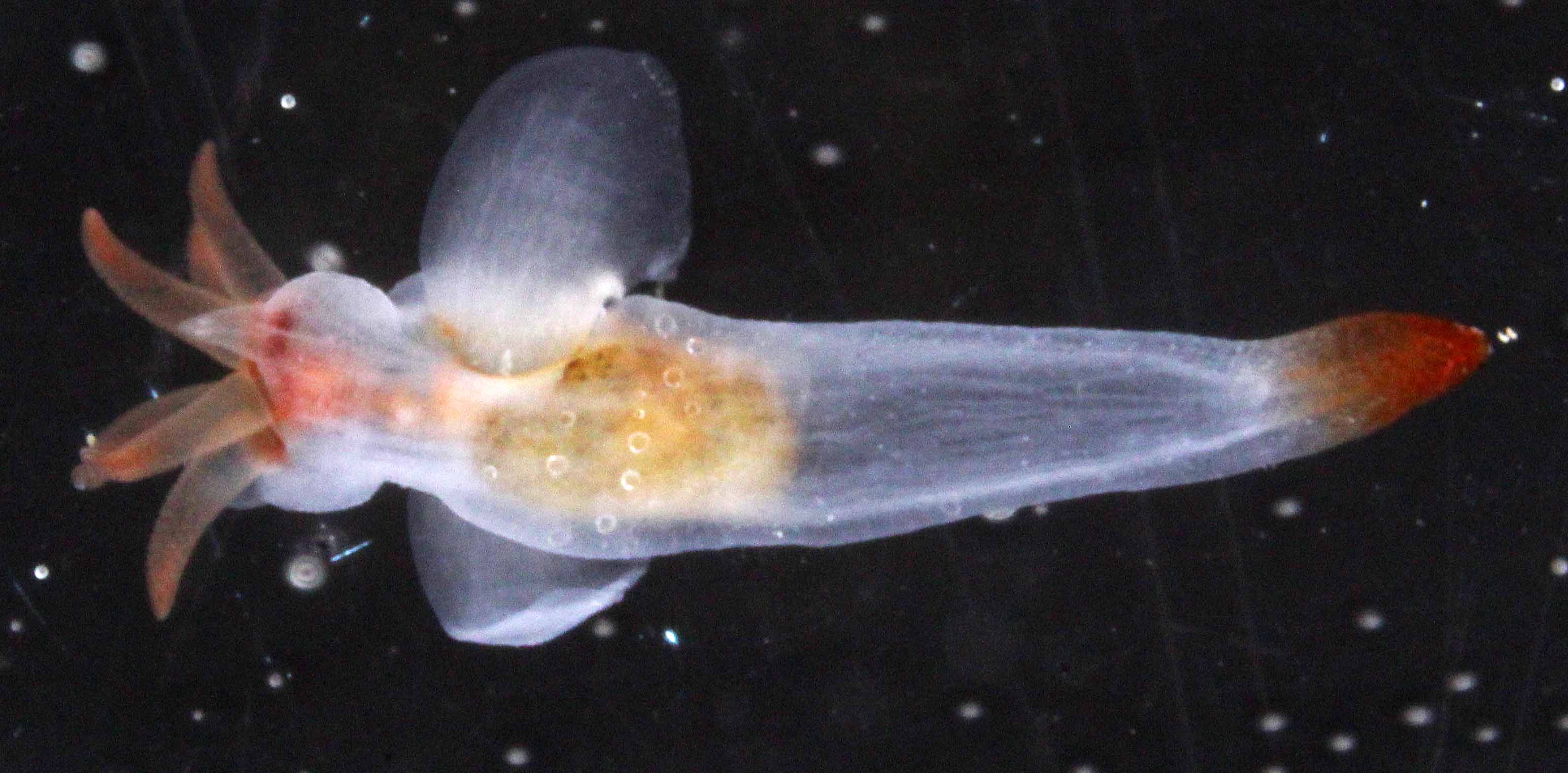

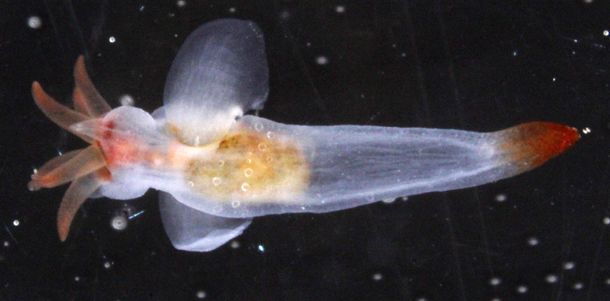

I do my PhD on the evolution and phylogeny of pteropods, my main interest is the sampling of specimens of Limacina helicina and its predator Clione limacina (see picture), generally known as “sea angel”. Besides that I enjoy exploring the diversity of arctic gastropods in general.

I do my PhD on the evolution and phylogeny of pteropods, my main interest is the sampling of specimens of Limacina helicina and its predator Clione limacina (see picture), generally known as “sea angel”. Besides that I enjoy exploring the diversity of arctic gastropods in general.

Maria Perpétua Scarlet (Gothenburg University):

The small (10-13 length), fragile bivalve shells of the species Ennucula tenuis, are beautiful, olive-yellowish or brown in color outside and nacreous inside; tho specimen was dredged at 50 m depth on mud of Eqalunguit, Disko Fjord.

Sandra Lage (Stockholm University):

Ceratium fusus found in the surroundings of Disko Island, is my favorite organism of the day. You can find them everywhere, from Tropics to the Arctic, the marine and fresh waters teem with life; a so tiny…microscopic life that ultimately all trophic chains depends on. While most of these species of phytoplankton and cyanobacteria are harmless, there are a few that create potent toxins given the right conditions, and this are the ones that I have been always fascinated about.

Edited by: Sandra Lage (Stockholm University) and Christiane Todt (University Museum of Bergen)

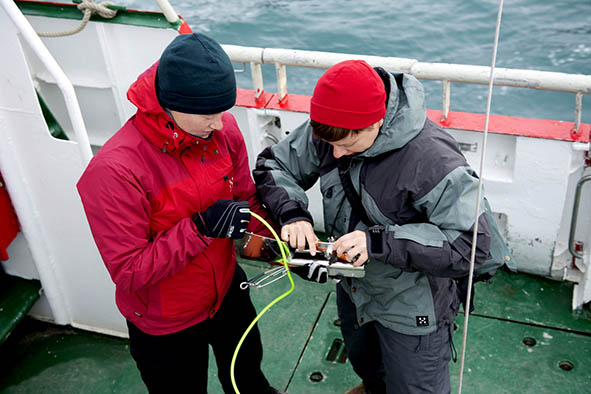

Last days in the lab: full house! The underwater film team: Mette and Jenny

Last days in the lab: full house! The underwater film team: Mette and Jenny