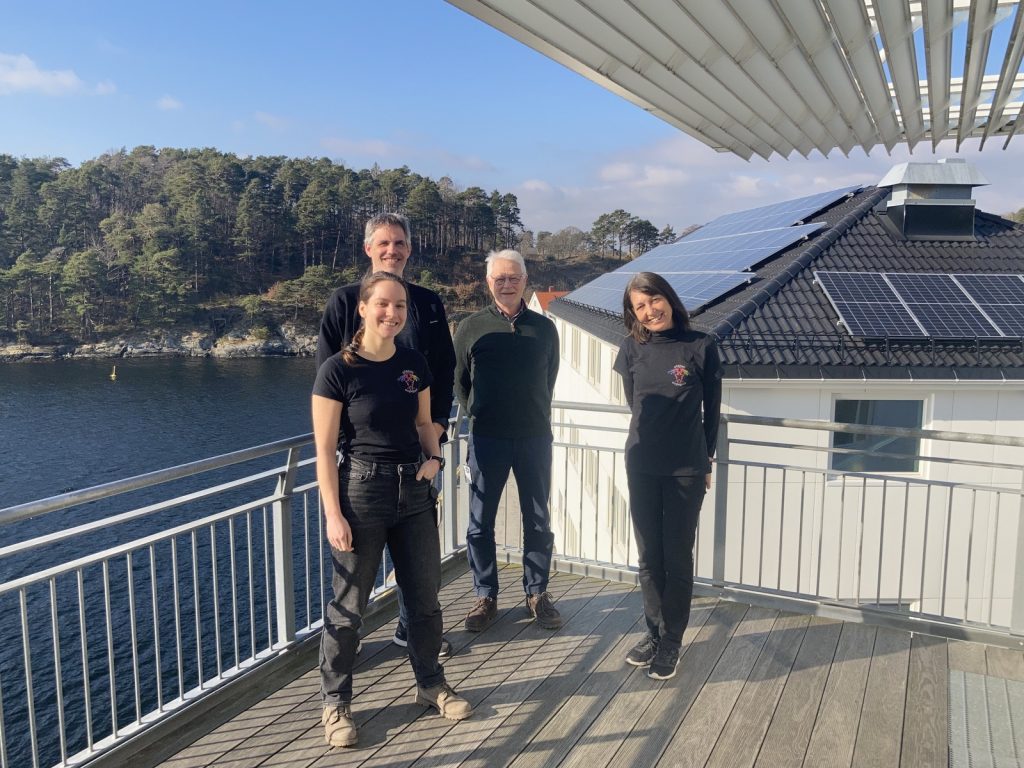

Last month, our project NorHydro (together with ForBio Research School of Biosystematics and project MEDUSA) organized a course on diversity, systematics and biology of Hydrozoa at the Marine Biological Station in Espegrend. Fifteen participants from 9 different countries came all the way to Bergen to learn more about these intriguing animals, share their ideas and projects, and start new collaborations. We asked one of the youngest members of the group –our highly motivated student Ana González– to share with us her thoughts about the course and her experiences with her MSc project. This is what she had to say:

When I started my Master’s Degree of Marine Ecology at the University of the Balearic IslandsI already knew about the existence of hydrozoans, but I had no idea how interesting these animals actually were. After some discussions, a lot of reading, and a fair amount of looking at pictures of hydroids and hydromedusae, I decided to work with these inconspicuous invertebrates for my MSc project under the supervision of Dr Luis Martell (University Museum of Bergen) and Dr. Maria Capa (University of the Balearic Islands). My project aims to evaluate whether we can use the benthic communities of hydrozoans as bioindicators of anthropogenic impact on the easternmost coasts of Mallorca Island, in the Mediterranean Sea.

Me on a sampling day looking for benthic hydrozoans at the marine reserve of Cala Gat (top). A closer view of the hard substrates I sample in the marine reserve (bottom left). The common hydroid Monotheca obliqua growing on Posidonia oceanica (bottom right). Picture credits: Maria Capa and Ana González.

Coastal areas are an attractive place to live, and these habitats provide ecosystem services that contribute greatly to the economy of the world, but a bad management of them can generate important damages and drastic changes in the ecosystem. One way to monitor environmental impacts in these habitats is by observing the response of their biological communities, so for this project I decided to study the assemblages of benthic hydrozoans in two opposite sites with different levels of anthropogenic impact: a harbor and a marine reserve. Moreover, I am comparing the communities in different seasons of the year, and I will analyze the assemblages growing on hard substrates (like rocks) and also those growing on a very important Mediterranean soft substrate: the endemic seagrass Posidonia oceanica.

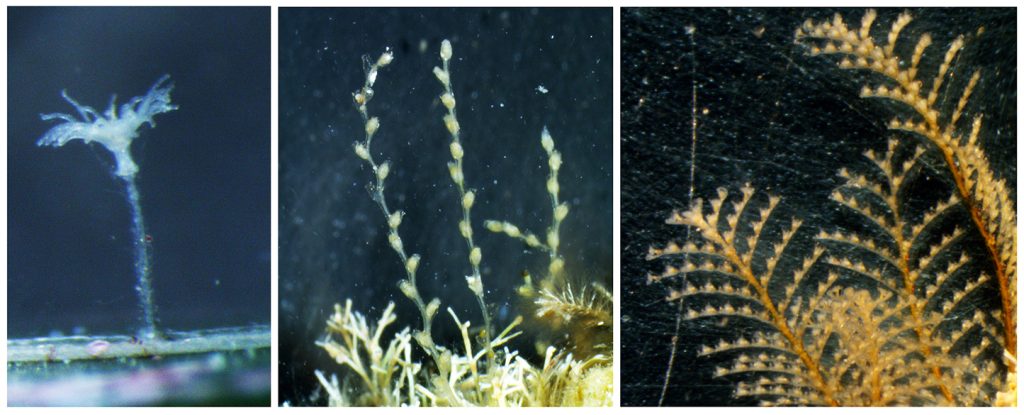

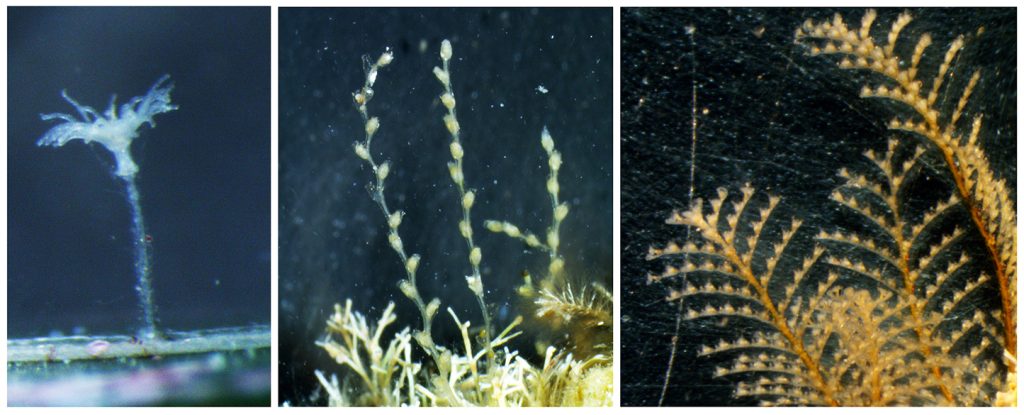

Some hydroids common in my study area are those belonging to genera Clytia (family Campanulariidae, left), Sertularella (family Sertularellidae, middle), and Aglaophenia (family Aglaopheniidae, right). Picture credits: Ana González.

At the beginning, working with benthic hydrozoans was very challenging for me since the specimens I find are easily overlooked if one is not searching carefully for them. But the more time I dedicate to observe these organisms, the more curious I became about their identity and dynamics, and the easier it was to recognize them in the samples. However, identifying hydrozoans is a difficult task and I realized early that I needed some help, so I was very happy when the opportunity arose to apply for the course “Diversity, Systematics and Biology of Hydrozoa” in Bergen. There, I had the chance to meet some of the leading scientific experts in the field that helped me understand better the taxonomy and ecology of these animals. I couldn’t have imagined how much I was going to learn during the different activities of the course, but at the end these organisms were able to catch my attention and time flew between lectures, sampling trips, and laboratory work. One aspect of the course that I particularly enjoyed is the fact that it brought together participants with different trajectories in science, and everybody was happy to share their experiences in the world of hydrozoan science.

We had all kinds of weather during the course: rain, sun, wind, and even snow! Picture credits: Lara Beckmann and Joan J Soto Àngel.

We had the chance to sample on board the UiB research vessel Hans Brattström and we collected several planktonic and benthic hydrozoans in the fjords around the Marine Station. After each sampling event, we went back to the lab to sort the samples, find the hydrozoans and identify them to species. The plankton samples were usually the first ones to be processed, since hydromedusae are quite fragile and they tend to suffer morphological damages after being sampled with a net. We tried to identify all specimens to species level, with the aid of the stereomicroscopes and scientific literature with identification keys that the curse provided. The benthic samples were placed in aquariums to keep the organisms alive and then each of us had the opportunity to observe the specimens in our own stereomicroscope.

A sampling day on board of RV Hans Brattström. Top left: deploying the plankton net. Top right: a full cod-end with plankton sample. Middle right: students and teachers ready to leave the pier. Bottom: benthos sampling with the triangular dredge. Picture credits: Lara Beckmann, Sabine Holst, Luis Martell

Top right and left: students and teachers at the laboratory, identifying hydrozoans. Bottom left: searching for hydromedusae and siphonophores in the plankton sample. Picture credits: Sabine Holst and Lara Beckmann.

All together, we were able to find and identify more than 40 species from all the main groups of hydrozoans, including siphonophores, trachylines, leptothecathes, and anthoathecates. Working with hydromedusae was new for me and I discovered that observing them was more challenging than identifying the polyps, but it was also interesting in its own way. The hydrozoans that caught my attention the most were the polyps from the suborder Capitata, because their morphology is very different from the hydroids that I have observed in my MSc project so far. Capitate hydroids don’t have a protective theca, they possess tentacles that end up in a ball of nematocysts (so-called capitate tentacles), and they are absent from almost all my samples from Mallorca, which are instead dominated by hydroids belonging to the Order Lepthothecata.

Top: Colony of Sarsia lovenii (Anthoathecata: Corynidae) with gonophores (i.e. reproductive buds on the polyp body). You can also see the capitate tentacles, which end in a ball of nematocysts and are typical for suborder Capitata. Bottom: Colony of Clava multicornis showing also gonophores on the polyp body, but with filiform (non-capitate) tentacles. Picture credits: Lara Beckmann (top), Joan J. Soto Àngel (bottom).

My interest for hydrozoans, the great set of experts we had as teachers, and the charismatic animals that we collected were the perfect combination for me to have an incredible experience in this course. I think that courses like these are an excellent opportunity for beginners to learn with experts from different parts of the world. Interacting with all of these amazing people was very rewarding at both cultural and scientific levels, and this whole experience motivated me to keep on studying these interesting animals that are a part of the complex functioning of our oceans.

-Ana