HYPCOP (Hyperbenthic Copepoda) is a young project starting date May 2020 with joined efforts between researchers from the Institute of Marine Research (IMR; Tone Falkenhaug), Natural history museum of Bergen (UiB; Cessa Rauch, Francisca Correia de Carvalho, Jon Anders Kongsrud) and Norwegian Institute for water research (NIVA; Anders Høbæk). If you want to read more about what HYPCOP entails, read it all in our previous blog here: link to HYPCOP kickoff blog.

We were already off with a good start with having quite some fieldwork and sampling done this Summer in and around Bergen, Killstraumen, Lillesand, Drøbak and now with our most recent trip to Flødevigen. During week 35 (24 – 28 August), all the different researchers from HYPCOP traveled to the IMR fieldstation in Flødevigen to participate in a sampling excursion. It was a special event because it was the very first time since the project started that all the collaborators would meet, in real life! We had many meetings via the digital platforms but working together face to face is quite a different and more pleasant experience (Picture 1).

Team members at the field station; from ltr: Anders Hobæk (NIVA Bergen, Jon Kongsrud (UoB, Tone Falkenhaug (IMR), Cessa Rauch and Francisca de Carvahlo (UoB)

The HYPCOP project is special in many ways; besides the involvement of many different institutes, the team deals with quite a steep learning curve. As off now there are very few hyperbenthic copepoda taxonomists in the world and none in Norway. Anders Hobæk has experience with freshwater copepoda, however his skills are transferrable to the marine species, which helps us a lot. Tone Falkenhaug has experience with copepods from previous projects (COPCLAD; Inventory of marine Copepoda and Cladocera (Crustacea) in Norway). However, the difference between COPCLAD and HYPCOP is the habitat: COPCLAD invented the pelagic realm, while HYPCOP focuses on the Hyperbenthos.

We decided to use the few days we had together to start from scratch, which meant, first getting some samples from the water.

We all used different techniques to make sure we got copepods from different habitats;

Jon went for snorkeling;

Anders brought his miniature plankton net,

and Tone set her light traps out.

This ensured that we had a higher chance of getting different species to look at. Next we would look at our freshly caught samples under the microscope and tried to sort them based on morphotypes (as much as that is possible, as they move fast!).

Copepods can actually have very nice colors! Therefore, we prefer to take live images of the animals as well as when they are fixed on absolute ethanol. So, after sorting them, we continued to make pictures before fixing the animals ready for the next steps.

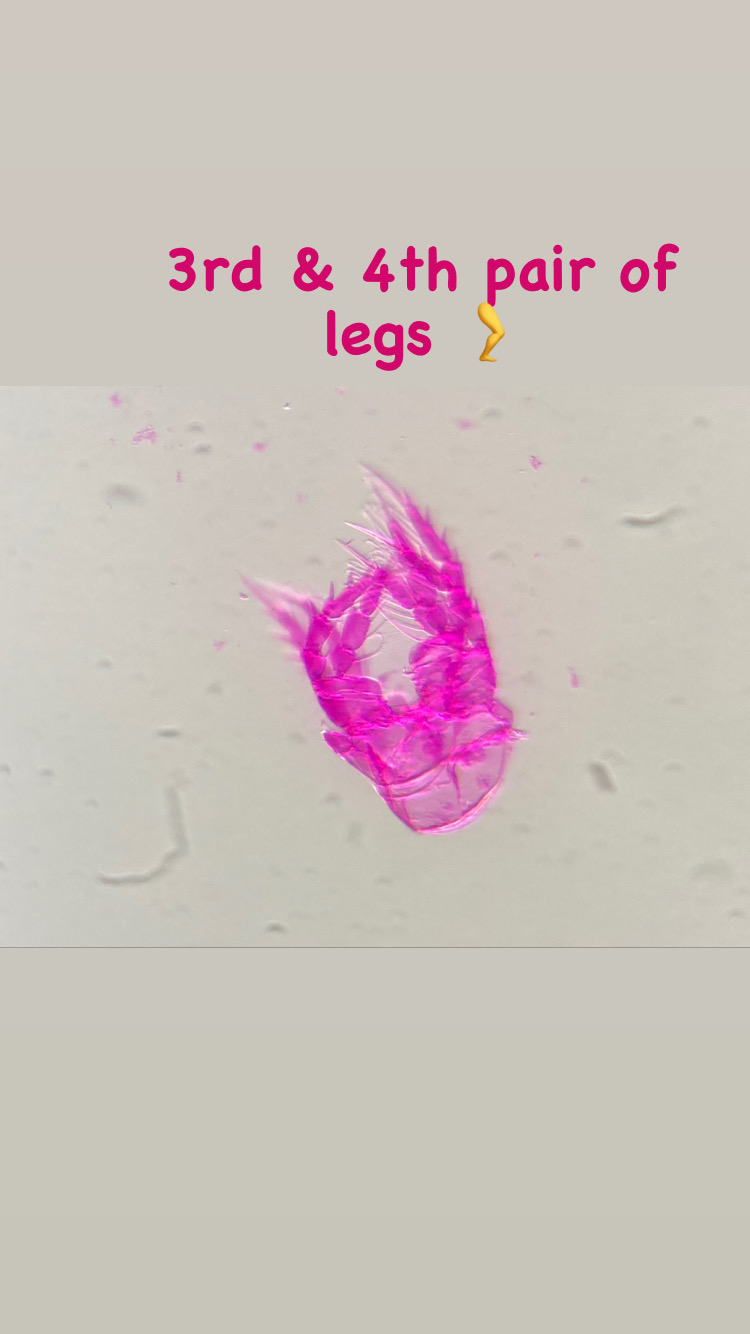

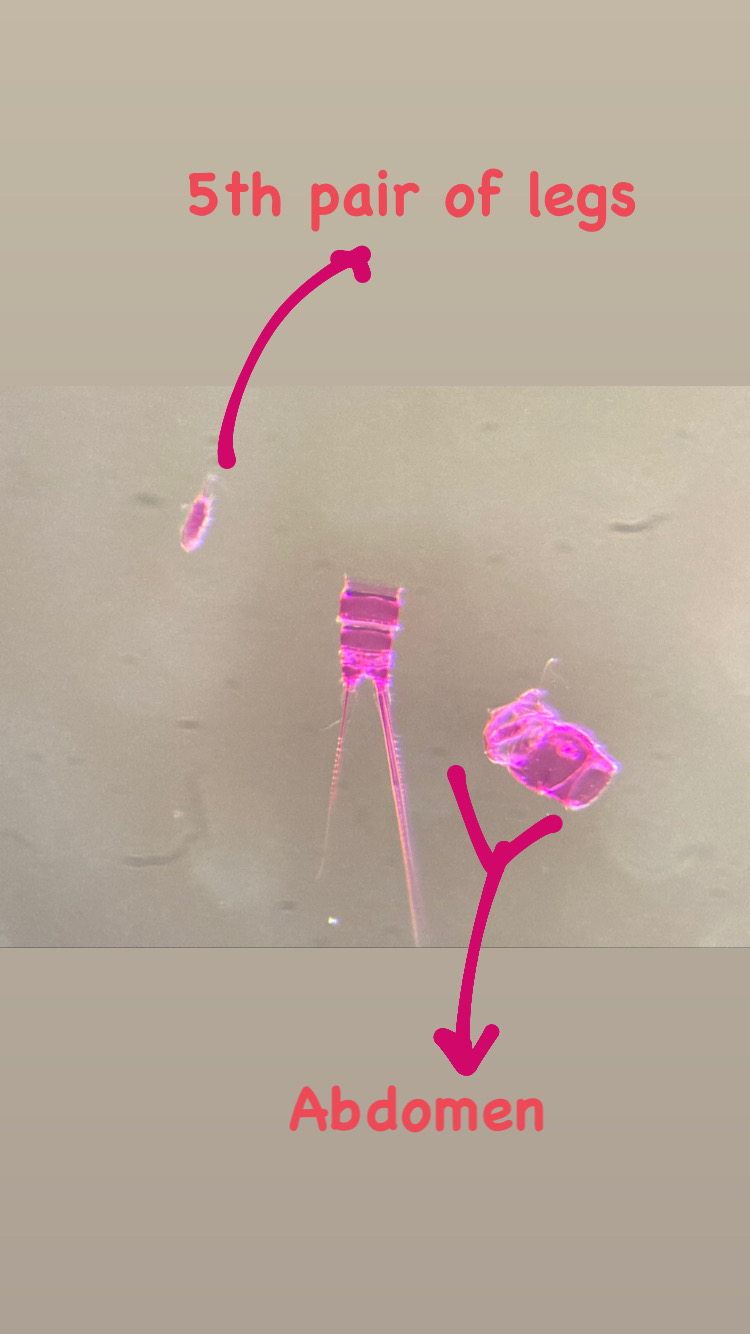

After fixing we experimented with different staining methods in order to make the exoskeleton of the copepods more visible for detecting important morphological features. An important part for species identification is studying the individual body parts of the animals, like the antennae, the individual pair of legs, the claws (maxillipeds).

The animals also have differences between males and females, so it is key to make sure that you identify it as the same species! With morphological identification it is important to also keep some specimens aside for genetic studies. Only when the DNA barcode and the morphological identification agrees we can be certain about the right species identification! As you can read there’s a lengthy process involved before we have the right identification of a copepod specimen and there are hundreds of species described for Norway alone! It is truly very extensive research! Follow us on Twitter and Instagram @planetcopepod to follow our story, or become a member of our planetcopepod Facebook group for the latest news and finding!

See you there!

-Cessa